Introduction

This report provides an overview of U.S. arms sales to the Middle East.1 The report includes

- brief information on U.S. arms sales to the region since the end of the Cold War;

- data on current arms sales by country, with reference to specific cases, as they relate to regional and global geopolitical developments; and

- analysis of how arms sales shape and reflect U.S. policy in the region in light of actions by Congress and the executive branch.

The data in this report is based on a combination of resources, chiefly CRS Report R44716, Conventional Arms Transfers to Developing Nations, 2008-2015, by [author name scrubbed]. This report also uses the State Department's World Military Expenditures and Arms Transfers (WMEAT) reports, as well as other official and unofficial open-source data.2

Role of Arms Sales in U.S. Policy

While scholars debate the relative effects of arms transfers between nations and the relationship between arms transfers and interstate behavior,3 arms sales are recognized widely as an important instrument of state power. States have many incentives to export arms. These incentives include enhancing the security of allies or partners; constraining the behavior of adversaries; using the prospect of arms transfers as leverage on governments' internal or external behavior; and creating the economies of scale necessary to support a domestic arms industry (see textbox below).4 U.S. arms exports sustain parts of the U.S. defense industrial base. Moreover, foreign sales constitute a relatively important part of the U.S. economy, constituting 6.2% of the value of all U.S. exports from 2007 and 2014, compared with a worldwide average of 0.8% over the same period and 1.9% for Russia (one of the United States' main competitors in this arena).5

Direct deployment of U.S. manpower and resources appears to feature less prominently in current U.S. public opinion and policy debates regarding future foreign policy approaches to the Middle East than was the case in the years following the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. Therefore, arms sales in the region may become a significant way for the United States and other external actors to influence Middle Eastern partners and political-military outcomes.6 On the other hand, U.S. reliance on arms sales as a policy tool places at least some responsibility for their use in the hands of partners who do not always share U.S. interests, follow internationally-acceptable rules of engagement, or have the same capabilities as U.S. forces.

Congress, through its oversight of U.S. arms sales, plays an important role in shaping U.S. policy in the region. In past eras when arms sales figured prominently in U.S. regional or global efforts, congressional actions and opinions in specific cases arguably had a significant effect on overall policy trajectories.

|

Arms Sales and Domestic Industry Arms sales are an important contributor to the U.S. aerospace and defense industry, a sector that directly employs over 1 million workers, with another 3 million working in support.7 According to one industry observer, international sales have made up 20 percent of U.S. firms' total sales in recent years, and industry executives reportedly expect that figure to grow.8 Middle Eastern states play a critical role in sustaining this industry. In early 2014, it was reported that, as the U.S. Navy looked to shift from the F-18 to the new Lockheed Martin-produced F-35, Boeing's F-18 assembly line in St. Louis, MO, could close within two and a half years. Similar projections were made for the F-15 production line, which would come to an end in 2019 after fulfilling a large order from Saudi Arabia. However, two large deals with other Middle Eastern partners (Kuwait and Qatar9) appeared to save those lines from closure and extend their operations into at least 2020. Similar dynamics have played out in South Carolina (where a potential deal with Bahrain for a number of F-16s could boost a Lockheed-Martin plant in the state),10 Ohio (where Saudi orders have sustained General Dynamics tank production in Lima),11 Massachusetts (home to Raytheon, whose production of the Patriot air and missile defense system was rejuvenated by a 2008 UAE deal),12 and elsewhere. House Defense Appropriations Subcommittee Chairwoman Kay Granger, in response to a Trump Administration decision to delay some military aid to Egypt, said that when sales are curtailed, "the companies and the workers that put that equipment together in the United States are hurt."13 Opponents of specific arms sales sometimes characterize these potential economic benefits as short-term or incommensurate with the potential downsides. During a June 2017 debate over sales of air munitions to Saudi Arabia, Senator Rand Paul criticized those who would justify the deal as "a jobs program," saying that "we are going to give money to people who behead you and crucify you to create jobs. That should never be the way we make a decision about arms sales in our country."14 |

The Demand for Arms in the Middle East

The Middle East is one of the most militarized regions in the world, featuring numerous conflicts or standoffs that involve nearly every state in the region. Israeli leaders, pointing to a series of perceived existential threats including several major wars between Israel and its neighbors, assert a continued need to maintain a large and technologically advanced military. Iran is seen as a threat not just by the United States and Israel, but by nearly every one of its neighbors in the Persian Gulf. Ongoing conflicts in places like Yemen, Syria, and Libya demonstrate the extent to which other states seek to influence outcomes through the use of their own military forces and through arms transfers to local partners.

Several additional factors have created an enormous demand for arms in the region. Many countries face transnational terrorist threats and, in some cases, domestic insurgencies. In addition, many states have large militaries that often play a prominent, even dominant, role in domestic and international politics. Advances in technology and capabilities have made some systems obsolete, creating a need for new acquisitions. Some have argued that the importance Middle Eastern governments evidently ascribe to large weapons purchases stems from the role of arms in building international credibility, as well as national pride and identity. These are strong incentives in a region where legitimacy is widely contested and where some states became independent less than half a century ago.15

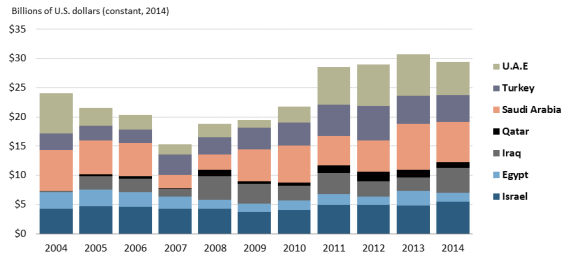

By almost every measure, the Middle East is a main participating region in the global arms trade, constituting 61.1% of the value of all arms agreements concluded by all suppliers with the developing world from 2012 to 2015, and 54.5% from 2008 to 2011. The Middle East has particular importance for the United States: arms from the United States made up 46.2% of all arms delivered to the Middle East from 2008 to 2011, and 45.8% between 2012 and 2015, outpacing those from the next largest supplier (Russia, whose deliveries totaled 19.1% and 17.5% of all deliveries to the Middle East, respectively).16 Those trends show no sign of slowing down in an increasingly militarized region:

- Of the 57 major U.S. arms sales proposed in 2016, 35 were to nations in the Middle East, totaling over $49 billion (or 78%) of the $63 billion aggregate total of proposed U.S. arms sales for that year.17

- In FY2017, the State Department announced $75.9 billion worth of proposed sales, $52 billion of which were to Middle Eastern states.18

- While three Middle East states had annual budgets putting them in the top 15 of global defense spenders in 2016 (Saudi Arabia, Israel, and Iraq, at 4th, 14th, and 15th, respectively), 6 out of the top 10 defense budgets as a percentage of GDP are in the Middle East (Oman, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Algeria, Israel, and Bahrain).19

In the Middle East over the past several decades, the United States has sought to utilize arms sales to reinforce major U.S. regional security policy priorities, including the following:

- 1. the security of Israel and the maintenance of its peace treaties with Egypt (1979) and Jordan (1994);

- 2. counterterrorism;

- 3. free access of the region's energy resources to global markets;

- 4. countering Iranian regional influence; and

- 5. U.S. regional partners' internal stability.

U.S. arms sales to the region have been subject to criticism by those who argue that such efforts have a moral cost and a detrimental effect on U.S. interests. U.S. sales have fueled what some characterize as a regional arms race,20 an ongoing concern of some U.S. policymakers.21 Some argue that weapons provided by the United States empower undemocratic regimes that repress human rights, creating the conditions for political instability.22 Others challenge the long-term financial and political viability of this arrangement, questioning U.S. partners' continued ability to purchase arms at such a high level in an age where lower oil prices have strained some nations' budgets. For some U.S. partners, maintaining high levels of arms procurements may result in less spending on infrastructure, education, and a level of service provision to which populations have become accustomed in recent decades.23

History of Congress and Arms Sales in the Middle East

Since the end of World War II, the Middle East has at times featured prominently in congressional deliberations over U.S. arms sales. Members' questions over specific arms sales to states in the region have helped frame the terms of the arms sales debate, and have shaped the broader, sometimes contentious relationship between the executive and legislative branches over U.S. foreign policy.

In the aftermath of World War II, the provision of arms became a major area of competition in the Cold War rivalry between the United States and Soviet Union. Through arms sales, the two superpowers sought to reinforce nations within their spheres of influence, and to entice nonaligned states to join. The Middle East was one of the most contested regions, with the United States providing weapons to partners like Saudi Arabia and prerevolutionary Iran, and Soviet weapons flowing to Egypt, Syria, and Iraq.

Some policymakers, reflecting currents within public opinion, reacted to this postwar military buildup with calls for a more measured approach, leading to the passage of the Arms Control and Disarmament Act in 1961, which began by declaring "a world ... free from the scourge of war and the dangers and burdens of armaments" to be the fundamental goal of U.S. policy. To achieve this goal, Congress created the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency (ACDA), an independent agency charged with coordinating research on international arms sales and managing U.S. participation in international meetings and negotiations convened to discuss arms control.

After the Nixon Administration acted unilaterally with regard to specific arms transactions with Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Kuwait, Congress passed the Foreign Assistance Act of 1974 (P.L. 93-559), which laid the basis for the system that still exists in its essential form today.24 The Nelson-Bingham Amendment to the act required the President to notify Congress of government-to-government arms sales above $25 million, after which Congress would have 20 calendar days to veto the sale by concurrent resolution. Nelson-Bingham was quickly put to the test when the Ford Administration informed Congress in July 1975 of its intent to sell a number of air defense missile batteries to Jordan. Congressional concerns over the security of Israel (whose government opposed the sale), and over the fact that Congress was not consulted in advance, led the Ford Administration to withdraw the sale. The sale went through later in the year after a number of modifications mollified those concerns.25 The episode marked an important precedent in the establishment of congressional prerogatives over arms sales.26

The International Security Assistance and Arms Export Control Act of 1976 (AECA, P.L. 94-329) further refined the process by which Congress reviews arms sales proposed by the executive branch. As amended, the AECA requires that, for sales over a certain valuation, the administration must provide formal notification 30 calendar days before taking steps to conclude the sale, during which time Congress may adopt a joint resolution of disapproval, which, if signed by the President, will prevent the sale from going forward.27 Dozens of resolutions of disapproval have been introduced, with the majority related to proposed sales to Middle East countries (see Appendix B). To date, no sale has been blocked as a result of a joint resolution of disapproval.

However, in some cases, congressional scrutiny, skepticism, or adoption of such a resolution has arguably contributed to preventing or delaying arms sales to Middle East countries, or to altering the terms of sale. For example, after 64 Senators sent a letter to the White House indicating their opposition to elements of a proposed arms package for Saudi Arabia in 1987, the Reagan Administration dropped the inclusion of Maverick antitank missiles to secure approval for the remaining items.28 In 1996, congressional concern about the conduct of Turkey's war against Kurdish insurgents delayed the sale of 10 Cobra helicopters for several months until the Turkish government canceled the deal in favor of leasing helicopters from other sources.29

The closest Congress has come to blocking a sale legislatively came in 1986, when both the House and the Senate adopted by veto-proof majorities legislation to block a proposed sale of several hundred Sidewinder, Harpoon, and Stinger missiles to Saudi Arabia. President Reagan vetoed the legislation (S.J.Res. 316) but decided to drop the Stinger missiles from the sale. This was enough to save the rest of the deal, the blocking of which failed by a single vote, 66-34. More recently, proposed legislation to block specific sales of weapon systems to Saudi Arabia did not garner sufficient vote to pass in September 2016 (27-71) and June 2017 (47-53); for more, see "Saudi-Led Coalition War in Yemen" below.

Arms Sales and Regional Developments

Overview of Major Outside Suppliers

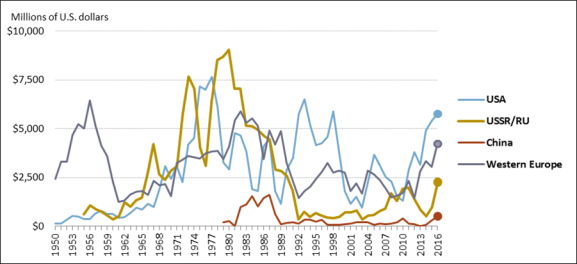

A small number of actors provide most of the external supply of weapons to the Middle East. By every measure, the United States has been the single largest seller of arms to the region for over two decades (before which it contended with the Soviet Union for supremacy in this regard; see Figure 1), a reflection of both the technological superiority of its arms as well as its active role in the region. The United States appears to be trying to maintain that influence amid conflicting domestic and foreign policy imperatives.30 Many Middle Eastern states view Russia either as a genuine alternative supplier or as a second option whose presence might increase regional buyers' leverage with U.S. officials and exporters. Indeed, several examples below demonstrate this dynamic.

Russia's interest in the region appears to be motivated by both geopolitical considerations and its relative comparative advantage in the arms trade.31 European suppliers, while less centrally involved with regional arms sales than they were several decades ago, remain players—despite signs that at least some of them appear increasingly conflicted about profit imperatives versus human rights.32

Relative newcomer China may be testing waters in the region and making observations to inform its own industry and strategic goals, particularly with regard to the sale of advanced technologies (such as drones) that other suppliers are reluctant to share. That said, China currently lags behind even most individual western European suppliers.33 The regional arms market is increasingly dynamic, with multiple states vying for advantages vis-a-vis rivals in terms of scale, technological innovation, and the cultivation of supplier relationships.

Major Regional Country Profiles

Israel

The United States, citing concerns about alienating other Middle Eastern states and inciting a regional arms race, was a limited arms supplier to Israel during its first two decades of existence.34 Israel relied mostly on France for its heavy weaponry, but it also employed some U.S. weapons, including tanks.

It was not until Israel's resounding victory against multiple Soviet-backed Arab states in the 1967 Six Day War that the United States began to reconsider the nature of its support. President Lyndon B. Johnson secured the sale of F-4 Phantom fighters to Israel in 1968, and the U.S. quadrupled its aid after the 1973 Yom Kippur War, during which the U.S. airlifted thousands of tons of defense equipment (including M60 tanks) to Israel. Some have traced U.S. support to the growing organization and effectiveness of domestic Israel advocacy groups starting in the 1970s.35

Israeli military imports—particularly in the realm of fighter aircraft and missile/missile defense technology—remain almost exclusively American. U.S. arms exports, funded at least in part by large amounts of U.S. aid, help maintain Israel's military advantage over its neighbors (see "Israel's Qualitative Military Edge" below), a reflection of the depth and breadth of U.S.-Israel ties. Moreover, Israel is a consortium partner in the development of the F-35 aircraft and recently became the first country outside the United States to receive F-35s.36 The probability of continued Israeli reliance on U.S. weapons and defense technology was demonstrated in the memorandum of understanding (MOU) the two countries concluded in September 2016. Under the terms of that MOU, which is the third between the two countries, the executive branch committed to request that Congress provide $38 billion in military aid over 10 years, from FY2019 to FY2028. (For more information on the MOU and its terms, see CRS Report RL33222, U.S. Foreign Aid to Israel, by [author name scrubbed]). Most of Israel's other major purchases made in recent years have been from Western European suppliers, including a 2012 deal with Italy for 30 M-346 jets, worth around $1 billion (the final planes were delivered in July 2016).37

|

Israeli Arms at a Glance: Fixed-wing combat aircraft: 59 F-15s (US), 219 F-16s (US) Fixed-wing transport aircraft: 5 C-130J-30s, 14 C-130s, 8 Boeing 707s (US) Rotary-wing combat aircraft: 45 AH-64 Apaches (US) Air defense: 4 Patriot batteries (US); 10 Iron Dome batteries (US), David's Sling (US, unknown number) Navy: 5 submarines (Germany), 38 fast-attack craft (10 missile, 28 gun; Israel), 3 missile corvettes (US/Israel) Artillery: 350 155 mm self-propelled howitzers (US) Armored vehicles: 1,030 battle tanks (Israel/US), 385 Armored Personnel Carriers (APCs, US/Israel) Total value of all Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCA) Foreign Military Sales (FMS) notifications since 2010: $9.6 billion Planned and potential procurements: 50 F-35s (U.S.), potentially F-15s (U.S.); 111 APCs (Israel); 4 submarines (Germany), 4 corvettes (Germany/Israel) Note: The information in this and the following national platforms/procurements textboxes is drawn almost entirely from Jane's by IHS Markit. |

Israel has an active and growing indigenous arms industry, the development of which has been subsidized in part by U.S. support. Since FY1984, Israel has been allowed to spend a portion of its U.S. Foreign Military Financing (FMF) assistance on arms produced by Israeli manufacturers (known as Off-Shore Procurement, or OSP).38 Israel is unique in this regard—no other FMF recipient can use any of the FMF for domestic procurement.

Although breaking out the exact role of U.S. OSP funding in the development of the Israeli arms industry is difficult, Israel's defense contractors have become competitive with other global leaders: from 2008 to 2015, Israel signed agreements to supply $12.8 billion worth of arms to other nations, the 10th highest figure in the world and not far behind such traditional suppliers as the United Kingdom and Italy. By one measurement, military exports from Israel grew by 14% in 2016, with Israel selling a diverse array of military systems and equipment to a number of countries, most prominently India.39 Some observers have raised concerns, going back to the late 1970s, about possible Israeli violations of the conditions under which U.S. assistance is provided, most notably the potentially unauthorized retransfer of U.S.-provided weapons to third-party states.40

Egypt

For the period 2008 to 2015, only two developing countries in the world (India and Saudi Arabia) signed arms agreements worth more in aggregate than those signed by Egypt, which totaled over $30 billion.41 Although formally at peace with its neighbors, Egypt has been a huge consumer of weapons, a product of its status as the biggest Arab state, its large and politically powerful military, and its strategically important geographic position (including administration of the Suez Canal). First a Soviet client during the Cold War, Egypt became a major market for U.S. arms in the late 1970s and 1980s, as the United States sought to entice and then reward and reinforce Egypt's pivot away from Soviet influence and its 1979 peace treaty with Israel.

|

Egyptian Arms at a Glance: Fixed-wing combat aircraft: 28 F-4s (US), 210 F-16s (US), 6 Rafales (France), 63 Mirages (France), 38 MiG-21MFs (USSR), 52 CAC F-7s (China) Fixed-wing transport aircraft: 22 C-130Hs (US), 3 An-74s (Ukraine), 9 DHC-5Ds (Canada), 22 C295Ms (international) Rotary-wing combat aircraft: 45 AH-64 Apaches (US), 55 SA 342 Gazelles (US) Air defense: 4 Patriot batteries; S-300VM (Russia) Navy: 4 submarines (USSR), 41 fast-attack craft (35 missile, 6 gun; USSR, Israel, US), 10 frigates (US, China, Spain, France), 2 Mistrals (France), 1 missile corvette (Russia) Artillery: 565 155 mm self-propelled howitzers (US) Armored vehicles: 1,050 battle tanks (US), hundreds of APCs (USSR, US, Egypt) Total value of all DSCA FMS notifications since 2010: $2.1 billion Planned and potential procurements: 24 Rafales (France), unknown number of MiG-29Ms (Russia), 2 C-130Js (US), S-300VM (Russia), 4 submarines (Germany), tanks (Russia) |

As part of this support, Egypt has consistently been one of the world's highest recipients of FMF, which it uses exclusively to purchase U.S. weapons. But political turmoil in Egypt since 2011 and repressive measures that the government of President Abdel Fattah al Sisi has taken against domestic opponents after Sisi overthrew the elected government in 2013 have contributed to tension between the United States and Egypt, complicating bilateral relations. Within this context, Egypt's government has sought sources of major defense systems beyond the United States.

From 2008 to 2011, fully 76% of Egyptian arms acquisitions came from the United States; that figure dropped to 49% from 2012 to 2015, as Western European (30%) and Russian (13%) suppliers stepped in to fill the gap. Most of Egypt's military assets (including both its air fleet and many of its tanks) are divided between higher-end American equipment and older Eastern European systems. Although diversification may lessen Egypt's dependence on any one supplier to some extent, it also raises the level of complexity Egypt faces in maintaining diverse weapons systems and juggling multiple supplier relationships.

Some specific recent transactions illustrate apparent Egyptian attempts to diversify in the aftermath of the Obama Administration's reaction to the 2013 military intervention. In February 2014, Egypt signed a $3 billion weapons deal with Russia. Two months later, the United States went through with a sale of Apache helicopters that had been frozen because of the 2013 military intervention and its aftermath, although the Obama Administration continued to withhold delivery of more than a dozen F-16s. That delay ended in March 2015, and the F-16s arrived in Egypt in November of that year. Meanwhile, Egypt has strengthened its relationship with European suppliers, especially France, despite European uneasiness regarding Sisi's post-2013 crackdown against dissent. Egypt and France concluded a $5.2 billion deal for 24 Rafale fighter jets in February 2015, and seven months later, Egypt agreed to buy two Mistral helicopter carriers for more than $1 billion.42 The two countries signed another agreement, worth more than $1 billion, in April 2016 for additional ships, fighter jets, and a military satellite communication system.43

Saudi Arabia

|

President Trump Announces Plans for New Saudi Arms Sales During his May 2017 visit to Saudi Arabia, President Trump highlighted plans for a series of arms sales to Saudi Arabia, reportedly totaling $110 billion. The agreement would include seven arms sales previously approved by the Obama Administration (going back as far as 2013) for items including combat ships, Abrams tanks, and Chinook helicopters, all of which total around $24 billion.44 The remaining components would be approximately $14 billion worth of sales that the kingdom has already requested (in the form of letters of agreement, or LOAs) and that the Trump Administration reportedly supports but about which they had not yet notified Congress in May, and nearly $85 billion in potential sales that the Administration reportedly offered to the Saudis (in the form of memos of intent, or MOIs). The latter category reportedly includes such items as seven Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) batteries, over 100,000 air-to-ground munitions, and 4 frigates.45 Since the package was announced on May 20, 2017, the Administration has notified Congress of some proposed sales. |

Saudi Arabia has been one of the largest purchasers of U.S. arms by value and volume, though decades of U.S.-Saudi weapons transactions have at times been accompanied by public controversy and vigorous congressional debate. The Obama and Trump Administrations have notified Congress of proposed arms sales with a potential aggregate value of more than $120 billion from 2009 to the present, reflecting the putative importance of Saudi Arabia to U.S. strategy in the Middle East. President Trump announced several proposed arms sales to Saudi Arabia during his first foreign trip in office in May 2017 (see textbox). The technologically-advanced and often historic amounts of arms transfers both reflect and reinforce U.S.-Saudi ties. However, the relationship has been challenged by differences over the Iran nuclear agreement (which Saudi Arabia initially opposed but now supports), historic Saudi animosity to Israel, continued U.S. concerns regarding Saudi domestic governance and actions with regard to international terrorism, and the kingdom's regional activities (such as the war in Yemen).

Saudi Arabia has tried to diversify its arms sources, including through a concerted effort in recent years to expand its own defense industrial base. In May 2017, shortly before President Trump's visit, Deputy Crown Prince (and now Crown Prince) Mohammed bin Salman announced the creation of a government-owned company called Saudi Arabian Military Industries (SAMI) to manage production of air and land systems, weapons and missiles, and defense electronics (perhaps in imitation of the UAE's much more established state arms conglomerate, the Emirates Defense Industries Company or EDIC; more below). The establishment of SAMI represents a step toward the government's goal that 50% of Saudi military procurement spending be domestic by 2030.46 Several parts of a potentially high-value package of arms sales announced during the President's May visit include arrangements for the actual production of certain items to be carried out in Saudi Arabia. For example, a $6 billion agreement between Lockheed Martin and the Saudi Technology Development and Investment Company (known by its Arabic acronym, TAQNIA) includes plans for the assembly of 150 Blackhawk helicopters in Saudi Arabia.47

|

Saudi Arms at a Glance: Fixed-wing combat aircraft: 165 F-15s (US), 68 Tornados (Europe), 72 Typhoons (Europe) Fixed-wing transport aircraft: 34 C-130s (US), 4 CN235s (Spain) Rotary-wing combat aircraft: 48 AH-64 Apaches (US) Air defense: Patriot PAC-2 (US)(U.S.) Navy: 9 fast-attack craft (US), 7 frigates (France), 4 missile corvettes (US) Artillery: 161 155 mm self-propelled howitzers (US) Armored vehicles: 833 battle tanks (US), 1850 APCs (UK, France) Total value of all DSCA FMS notifications since 2010: $133.9 billion Planned and potential procurements: JF-17s (China/Pakistan), F-15SAs (US), An-132Ds (Ukraine), tanks (France/UAE), corvettes (Spain, France), littoral combat ships (US) |

U.S. reluctance or inability to share sensitive military technology, particularly in the field of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs, or drones), has periodically opened opportunities for other suppliers like Russia. Top military officials from the two nations had a meeting in Moscow in April 2017 at which Saudi Arabia, according to a Russian government account, provided a list of possible arms procurement requests.48 That was followed by a state visit by King Salman to Moscow in October 2017, the first ever by a Saudi monarch, during which Saudi Arabia reportedly agreed to a number of arms procurements, including S-400 missile defenses.49 China has also contemplated greater arms sales to Saudi Arabia, partly a legacy of its reported covert ballistic missile sales to Saudi Arabia in the 1980s.50 On a state visit to Beijing in March 2017, King Salman and President Xi Jinping signed a series of agreements worth $60 billion, including a deal to construct a Chinese factory in the kingdom that will manufacture military UAVs for Saudi Arabia's expanding drone fleet.51 Canada signed a $15 billion deal for armored vehicles with Riyadh in 2014.52

Turkey

Turkey has historically been one of the largest recipients of U.S. arms, owing to its status as a NATO ally, its large and politically powerful military, and its strategic position. Although Turkey straddles a number of disparate geographic regions, since the end of the Cold War its security focus has increasingly been to its south and east (the Middle East)—hence its inclusion in this report.

Roughly coinciding with the phase-out of U.S. FMF to Turkey in the 1990s and 2000s, and perhaps influenced to a degree by periodic delays or cancellations of proposed U.S.-Turkey arms deals due to congressional concerns,53 Turkey began reformulating its procurement strategy to include both new suppliers and increased domestic production.54 Yet, Turkey maintains key links with U.S. manufacturers, most importantly as a partner in the production of the F-35, of which Turkey ordered 100; the first delivery is expected in 2018. Turkey's approach rests on building up its domestic defense industry (including through technology-sharing and co-production arrangements with other countries) as much as possible, while minimizing "off-the-shelf" arms purchases from the United States and other countries.

|

Turkish Arms at a Glance: Fixed-wing combat aircraft: 238 F-16s (US), 36 F-4s (US) Fixed-wing transport aircraft: 19 C-130s (US), 12 C-160Ds (international), 48 CN235Ms (Spain) Rotary-wing combat aircraft: 55 AH-1 HueyCobras (US), 20 T129As (Turkey) Navy: 13 submarines (Turkey/Germany), 23 fast-attack craft (Germany/Turkey), 17 frigates (U.S./Germany/Turkey), 9 missile corvettes (France/Turkey) Artillery: 455 155 mm self-propelled howitzers (Turkey, South Korea) Armored vehicles: 1280 battle tanks (Germany/U.S.), 4000+ APCs (UK, Turkey, Russia) Total value of all DSCA FMS notifications since 2010: $1.1 billion Planned and potential procurements: F-35s (US), TF-X (Turkey/UK), MILGEM corvettes and frigates (Turkey), S-400 (Russia), SAMP/T Aster 30 missile system (France/Italy), tanks (Turkey) |

Recent Turkish actions regarding the procurement of air and missile defense systems are perhaps the most prominent examples of Turkey's willingness to range outside of its traditional security partnerships with the United States and other NATO countries to develop indigenous defense industrial capabilities. In 2013, Turkey announced a state-owned Chinese company as the preferred bidder for a missile defense system contract, over American (Patriot missile defense), European (SAMP/T), and Russian (S-400) competitors, sparking concern from Members of Congress and other observers regarding Turkey's commitment to NATO. Turkish officials, however, emphasized the lower cost of the Chinese system (known as the HQ-9) and greater willingness by the Chinese to transfer technology than was reflected in the U.S. or European offers.55 The tender was officially canceled in November 2015, but in March 2017, Turkish officials expressed a new interest in the Russian S-400 anti-air missile system.

After high-level negotiations, reports indicate that Turkey and Russia may have reached a preliminary $2.5 billion agreement in July 2017. President Erdogan said in September that Turkey has paid Russia an initial deposit for the system.56 Media reports state that the preliminary agreement provides that Turkey would receive two S-400 missile batteries within a year and then produce two others domestically.57 Turkish and U.S. officials say the S-400 is not interoperable with U.S. and NATO systems, and Senate Foreign Relations Committee Ranking Member Ben Cardin described the deal as a "troubling development."58 In a September 2017 letter to President Trump, Cardin, along with Senate Armed Services Committee Chairman John McCain, reportedly described Turkey's S-400 purchase as a potential violation of a law enacted in August 2017 that calls for sanctions on persons who engage in defense transactions with Russia.59 Other sources within NATO have characterized the deal as a "sovereign choice" or a "Turkish national decision."60

In addition, the Turkish government announced a preliminary deal in July 2017 to develop and jointly produce an air missile defense system with the majority Italian-French partnership Eurosam, possibly in an effort to assuage fears that the arrangements represent Turkey charting a path away from NATO.61 Turkish officials have characterized the S-400s as satisfying an "urgent requirement," perhaps in contrast with a longer-term cooperative arrangement envisioned with the Eurosam consortium.62 While the details are unclear regarding any technological transfer included as part of the deals with Russia and Eurosam,63 building domestic industrial capacity appears to remain an important consideration for Turkey. Some analysts observe that, despite the possible S-400 transaction, Russia is probably not inclined to significantly share technology with Turkey, given the two countries' past and continued geopolitical rivalry.64 However, U.S.-Turkey political tensions over issues such as U.S. support for Syrian Kurds or the status of U.S.-based Turkish cleric Fethullah Gulen (whom the Turkish government blames for the July 2016 coup attempt) may influence the extent to which Turkey considers U.S. objections to this or other non-NATO deals.

Turkey appears positioned to continue its focus on building up indigenous production and development capabilities, though it remains to be seen to what extent Turkey can become a major arms supplier in the region. The Turkish government has set a target of $25 billion worth of military exports by 2023, though that may be difficult given sales of $1.7 billion in 2016. Some have argued that the development of an indigenous arms industry is motivated more by domestic political considerations than strategic realities.65 However, research and development expenditures are up dramatically, and the Turkish Armed Forces now reports that 68% of its needs are met locally, compared with 25% in 2003.66

Human rights concerns, though no longer as prominent as they were in previous decades when U.S.-manufactured arms were more central to Turkish security, remain an issue as well (see below) and likely factor into Turkey's strategic calculus regarding arms purchases. In a possible attempt to expand the self-sufficiency of Turkey's defense industrial base to advanced aircraft, Turkey signed an agreement with the United Kingdom in January 2017 to cooperate on the TF-X, a future generation combat aircraft being developed by Turkey. One British minister described the deal as "a very important strategic initiative that we want to maintain and sustain over many years."67

UAE

U.S. arms are central to the UAE's growing military capabilities; major sales from the United States include the purchase of 80 F-16s in 2000 and an additional 30 in 2014.68 Moreover, the UAE's purchase of the THAAD missile defense system, initially proposed in 2008 and approved in late 2011, represented the first sale of the system abroad. However, like its close ally Saudi Arabia, the UAE appears to be attempting to both diversify its sources of arms imports and build up domestic production capacity, partly in response to concerns about U.S. policy. The UAE has long had a reported interest in purchasing F-35s. However, concerns about Israeli security, codified in laws mandating the preservation of Israel's military advantage (see "Israel's Qualitative Military Edge (QME)"), have been cited in some reports as a reason for the United States' not selling F-35s to the Emiratis, at least for several years after Israel receives its own F-35s.69

As a result, the Emiratis have evidently been looking elsewhere, specifically Russia, for advanced combat aircraft. Media reporting indicates that the two nations signed an agreement in the spring of 2017 to develop a fifth-generation fighter jet, along with a separate purchase by the UAE of Russian Sukhoi Su-35 fighters.70 It is unclear whether the UAE actually intends to implement the agreement or is more interested in gaining U.S. concessions on F-35s or other possible transactions due to U.S. concerns regarding Russia-UAE arms dealings.71 In addition, after being rebuffed in its attempts to purchase armed drones from the United States; the UAE reportedly purchased Chinese surveillance drones and outfitted them with targeting systems.72 Arms sales observers say such actions are not uncommon.

|

UAE Arms at a Glance: Fixed-wing combat aircraft: 79 F-16s (US), 42 Mirage 2000s (France) Fixed-wing transport aircraft: 9 C-130s (US), 7 CN235s (Spain), 8 C-17As (US) Rotary-wing combat aircraft: 18 AS 550 Fennecs (Europe), 30 407 MRHs (U.S./Canada), 29 AH-64 Apaches (US), 12 AS 350s (France) Air defense: 2 THAAD batteries (US) Navy: 9 corvettes (Germany, UAE, Italy), 26 fast-attack craft (Germany, UAE) Artillery: 165 155 mm self-propelled howitzers (US) Armored vehicles: 502 battle tanks (France, Italy), 682 APCs (Turkey, France, Spain, Finland/Poland) Total value of all DSCA FMS notifications since 2010: $23.7 billion Planned and potential procurements: Su-35s (Russia), 30 F-16s (US), Rafales or Typhoons (France, Europe), 6 corvettes (UAE), 1500 APCs (UAE) |

In terms of its indigenous arms industry, the UAE has been described as "the most promising of the Arab candidates seeking to gain emerging arms producer status."73 Established in 2014 from the consolidation of a number of state-owned firms, the Emirates Defense Industries Company (EDIC) represents an attempt not just to become less reliant on foreign suppliers, but also to diversify the Emirates' still largely hydrocarbon-based economy. Some observers point out that "domestic demand and consumption will dominate the formative years of indigenous industrial development,"74 but already EDIC has signed contracts with foreign customers from Algeria to Russia to Kuwait.75 The use of UAE equipment, including locally made armored vehicles, assault rifles, and personnel carriers, has figured prominently in the Saudi-led coalition's war in Yemen. It also has been a factor in Libya, where the UAE has reportedly operated drones and attack helicopters, perhaps in violation of a U.N. arms embargo.76

Iraq

Since 2011, the United States has proposed more than $28 billion in foreign military sales to Iraq, including a $2.3 billion sale of 18 F-16s in 2011 and a $4.8 billion sale of 24 Apache helicopters in 2014 that has not been implemented.77 Sales continued after the Islamic State (IS, also known as ISIL, ISIS, or the Arabic acronym Da'esh) swept into northern Iraq in July 2014, with $2.4 billion for 175 Abrams tanks proposed in December 2014 and nearly $2 billion for F-16 munitions in January 2016. While Iraq has purchased major weapons systems from the United States, it has also periodically shown an interest in diversifying the sources from which it obtains arms. Iraq has finalized major arms purchases from smaller suppliers, such as South Korea and the Czech Republic, and has a considerable amount of Russian-origin equipment, a legacy of its past supply relationship with the Soviet Union. A $4.2 billion arms deal between Iraq and Russia was announced in October 2012 but was reportedly put on hold a few weeks later,78 but one component of the deal, an order of Mi-28 Havoc "Night Hunter" attack helicopters, has actually been delivered and is in use against IS forces.79 Details of a potential $2.5 billion deal with China, first reported in late 2016, for the HQ-9 air defense system (among other orders) have not been officially clarified.80

|

Iraqi Arms at a Glance: Fixed-wing combat aircraft: 22 F-16s (US), 21 Su-25s (Russia), 3 L-159As (Czech Republic), 2 AC-208Bs (US) Fixed-wing transport aircraft: 3 C-130Es , 6 An-32s (Ukraine), 6 C-130J-30s Rotary-wing combat aircraft: 6 SA 341 Gazelles (international), 30 Bell 407s (Canada/U.S.), 19 Mi-24s (Russia), 15 Mi-28s (Russia) Air defense: 24 Patsyr systems (Russia) Navy: patrol craft (Italy, U.S., China) Artillery: 24 155 mm self-propelled howitzers (US) Armored vehicles: 255 battle tanks (Czech Republic, U.S., USSR) France, Italy), 1000+ APCs (U.S., Ukraine, USSR, UK, Pakistan) Total value of all DSCA FMS notifications since 2010: $33.7 billion Planned and potential procurements: AT-6 Texans (US), F-16s (US), Su-25s (Russia), upgrades to two currently unserviceable corvettes, AH-64 Apaches (US), 73 tanks (Russia) |

In February 2014, it was reported that Iraq had agreed, in November 2013, to purchase approximately $200 million worth of weapons (including mortars, ammunition, and light and medium arms) from Iran, allegedly spurred by frustration on the part of then-Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki about the slow pace of deliveries from the United States. Some observers viewed the deal, which appeared to violate a then-operative U.N. ban on the sale of Iranian weapons to any other state (UNSCR 1747), as both a message to the United States and a bid for greater support from Iran.81 Iraqi officials have acknowledged and welcomed Iranian military assistance and advice to their national security forces since 2014, likening Iranian support to support received from other foreign parties, including the United States. Iran is also widely-believed to be supplying some Shia militias fighting the Islamic State alongside Iraqi forces, including some forces of concern to Iraqi national government officials and the United States.

As the U.S. role and presence in Iraq shifts from an active focus on supporting Iraqi operations to one more focused on training and equipping Iraqi forces, the structure and terms of U.S. security assistance may become an issue of greater prominence in the bilateral relationship. Reflecting Iraq's needs, current fiscal difficulties, and status as a major oil exporter, the United States blends U.S.-funded programming with lending and credit guarantees. FMF assistance to Iraq supports the cost of U.S. FMF loans, which continue to fund Iraqi purchases of U.S. equipment. In addition, the sale of U.S. arms to the forces of the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) has been approved by Iraqi national government authorities, but sales to both entities could attract scrutiny if KRG-Baghdad relations sour.

As with a number of other Middle East partners, Iraq's human rights record has been a subject of concern for some Members of Congress. The behavior of the Iraqi military in the face of the Islamic State's 2014 offensive, when thousands of U.S.-supplied items were captured by IS fighters to be turned on Iraqi forces, other anti-IS fighters, and civilians, has attracted additional scrutiny. For more on both, see "Providing Weaponry to Governments Suspected of Human Rights" and "End-Use Monitoring (EUM)," below.

Qatar

|

Qatari Arms at a Glance: Select Platforms and Procurements Fixed-wing combat aircraft: 9 Mirage 2000s (France) Fixed-wing transport aircraft: 6 C-17As (US), 4 C-130J-30s (US) Rotary-wing combat aircraft: 11 SA 342 Gazelles (international), 8 WS.61 Commando Mk 3s (US) Air defense: 10 Patriot PAC-3 batteries (US) Navy: 3 fast-attack craft – missile (France) Artillery: 22 155 mm self-propelled howitzers (France) Armored vehicles: 70 battle tanks (Germany, France), 188 APCs (US, France) Total value of all DSCA FMS notifications since 2010: $47.9 billion Planned and potential procurements: 4 corvettes (Italy), 24 Rafales (France), 36 F-15QAs (US), 24 AH-64E Guardians (US), 2 C-17As (US) |

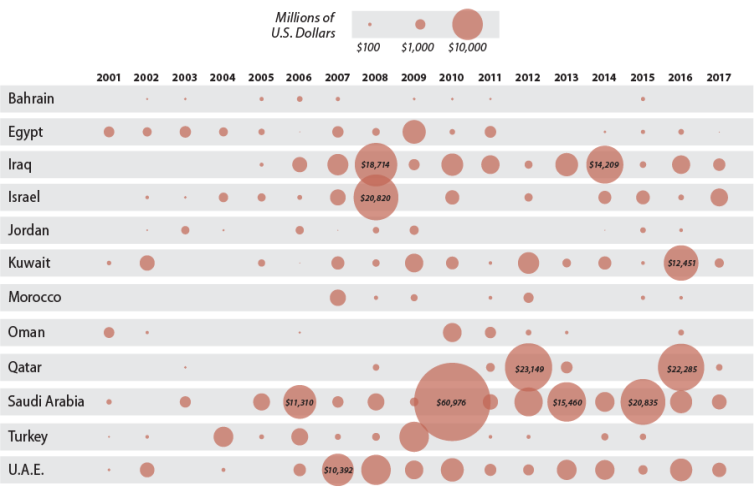

Located between its larger and more powerful neighbors Iran and Saudi Arabia, both of which it has tried (with varying levels of success) to maintain cordial relations with, Qatar has sought to solidify its relationship with the United States. According to one source, Qatar views U.S. support as "adequate compensation for appearing too close an ally to Washington."82 Qatar has had a formal defense cooperation agreement with the United States since 1992; the agreement was renewed for 10 years in December 2013.83 Qatar hosts the United States' 379th air expeditionary wing and a number of other U.S. and coalition assets at Al Udeid Air Base, including U.S. Central Command's (CENTCOM) Combined Air Operations Center.

Despite its small size and population, Qatar is increasingly recognized as an influential regional player, due in no small part to the increasingly broad array of military assets its considerable resource wealth allows it to obtain. In 2014, Qatar was the single largest customer of U.S. foreign military sales, purchasing over $10 billion worth of arms.84 The next year, in 2015, Qatar concluded $17.5 billion worth of arms transfer agreements, more than any other developed country.85 These included a total of $9.9 billion in contracts with the United States, and a $7.1 billion contract with France for 24 Rafale fighter jets and missiles. France has traditionally been Qatar's main arms provider, with hundreds of millions of dollars in weapons provided throughout the 1980s and 1990s. However, prior France-Qatar deals were surpassed and possibly superseded by a 2015 announcement that Qatar and the United States were proposing to enter into a transaction for up to 72 F-15QA aircraft worth over $21 billion; a letter of offer and acceptance for 36 jets, worth $12 billion, was signed in June 2017. Given that the Qatari air force currently consists of just nine combat aircraft (French Mirage 2000s), the additional Rafales and F-15QAs, initial deliveries of which are expected in mid-2018 and 2019, respectively, are likely to dramatically boost Qatari air capabilities. Newly ordered warships from Italy, the first in the Qatari fleet (see below), may do the same at sea.86

Recent deals with Qatar are emblematic of another factor important to U.S. military operators: interoperability. Reportedly, one of the reasons Qatar wanted to buy U.S. fighters to partially replace its French-made Mirages, "was because they discovered how difficult it was for their existing fighter aircraft to fly with the U.S. air force as part of coalitions over Libya and Syria."87

U.S. Policy and Potential Issues for Congress

The countries above and their respective approaches to arms sales affect U.S. foreign policy objectives and congressional interests in multiple ways. This section outlines related issues that Congress may wish to consider via the legislative process (including authorization and appropriations) and/or oversight.

Israel's Qualitative Military Edge (QME)

The term "qualitative military edge" (QME) was embraced by the Reagan Administration and its successors to refer to the advantage in military technology that Israel, with a smaller territory and population than some of its historical adversaries, seeks to maintain.88 The concept stems from traditional security concerns about Israel's Arab neighbors, with whom Israel engaged in numerous conflicts over the course of several decades. No formal definition in law existed until lawmakers codified U.S. support for Israel's QME as U.S. policy in 2008 (P.L. 110-429,§201).89 That legislation requires that any proposed U.S. arms sale to "any country in the Middle East other than Israel" must include a notification to Congress with a "determination that the sale or export of such would not adversely affect Israel's qualitative military edge over military threats to Israel." It defines QME as

the ability to counter and defeat any credible conventional military threat from any individual state or possible coalition of states or from non-state actors, while sustaining minimal damages and casualties, through the use of superior military means, possessed in sufficient quantity, including weapons, command, control, communication, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance capabilities that in their technical characteristics are superior in capability to those of such other individual or possible coalition of states or non-state actors.

During its review of several planned sales over the years, Congress has considered Israeli concerns about arms transfers to some Arab states, including a 1981 sale of Airborne Warning and Control System (AWACS) surveillance planes (which ultimately occurred) and a 1986 effort to sell several classes of missiles, both to Saudi Arabia. In the former case, Israeli concerns over plans to sell certain precision-guided weapons to Saudi Arabia and other Persian Gulf states delayed a major arms sales package that the George W. Bush Administration contemplated in 2007.90 However, Israel now views Iran as a top security challenge, a view shared by Saudi Arabia and other historic Israeli adversaries in the region. Increasing levels of Israeli alignment and even cooperation with Arab states in combatting shared threats from Iran and its allies, as well as the Islamic State and other terrorist groups, might inform future evaluations of the role of Israel's QME in U.S. arms sales to the region.91

QME concerns may have played a role in the large sale of F-15s to Qatar in 2016, which Israel reportedly opposed, accusing Qatar-based television channel Al Jazeera of incitement and citing Qatari support for Hamas.92 Some suggested that "Israel sought to leverage the Qatar sales" to boost the amount of military assistance it was negotiating with the United States.93 The new U.S.-Israel 10-year memorandum of understanding (MOU) was signed in September 2016. Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chairman Bob Corker stated in July 2016 that "when the MOU is completed, hopefully as part of that, or shortly thereafter, these sales [to Qatar] will be completed." The State Department formally notified Congress about the Qatar sale on November 17, 2016.

In addition, the large package of arms sales to Saudi Arabia announced during President Trump's May 2017 visit to the kingdom has reportedly raised Israeli anxieties, with advocacy groups voicing concern and several ministers suggesting that the United States did not consult with Israel in advance.94 Still, opposition to the Saudi proposal appears muted in comparison to similar packages proposed in the past.95

Countering Iran

U.S. policy in the Middle East appears to be partly driven by a desire to constrain Iran's ability to threaten U.S. partners and/or assets in the region or to constrain the free flow of energy-related commerce through waterways such as the Strait of Hormuz. U.S. arms sales to regional partners are important in countering Iran; in addition to various types of aircraft, ballistic missile defense (BMD) and naval assets are key considerations in regional countries' defense postures.96

Attack by ballistic missiles has been identified by many observers as the "greatest strategic threat to the Gulf States," but success in constructing a unified, integrated missile defense has remained elusive since the early 1990s.97 All Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states have BMD capabilities, mostly from the United States in the form of Patriot Advanced Capability-3 (PAC-3) and THAAD systems, as well as various British, French, and Russian platforms.98 Many proposed U.S. arms sales to the Gulf have focused on improving these defense capabilities. For instance, a proposed $2 billion deal with the UAE for 60 Patriot Advanced Capability 3 (PAC-3) missiles, 100 Patriot Guidance Enhanced Missile-Tactical (GEM-T) missiles, and related support and equipment was described by the Defense Security Cooperation Agency in May 2017 as "consistent with U.S. initiatives to provide key allies in the region with modern systems that will enhance interoperability with U.S. forces and increase security."99 A $15 billion sale of THAAD missiles to Saudi Arabia proposed in October 2017 was similarly described as increasing "Saudi Arabia's capability to defend itself against the growing ballistic missile threat in the region" and supporting Saudi security "in the face of Iranian and other regional threats."100

Barriers to a unified GCC approach to missile defense include reluctance to share intelligence and disputes over where a central command would be located. In addition, smaller Gulf states are generally wary of ceding power to Saudi Arabia, the bloc's largest member and de facto leader.101 Some observe that the Gulf BMD challenge is "less about money and interceptors and more about GCC members' historical distrust and reluctance to work together."102 Some Members of Congress appear to focus closely on questions of GCC unity, particularly in light of a continuing rift among leading GCC countries and Qatar. In June 2017, Chairman Corker announced that he would withhold preliminary (i.e., pre-notification) approval of all future arms sales to GCC states until Congress could obtain "a better understanding of the path to resolve the current dispute."103

Sales of various naval systems to GCC states have also been an important part of U.S. strategy to counter Iran. The arms package announced by the Trump Administration (discussed above) after the President's trip to Saudi Arabia included a $6 billion sale of four Multi-Mission Surface Combatant Ships (MMSCs, more heavily armed versions of the Littoral Combat Ship), about which Congress was originally notified in October 2015. Press reporting indicates that the Saudis may later purchase an additional four MMSCs.104 Similarly, Qatar has taken steps toward obtaining its first warships, announcing a $6 billion deal with Italy to purchase seven vessels (including four corvettes) in August 2017.105 As U.S. naval forces in the Gulf report increased levels of "unsafe" and "unprofessional" confrontations carried out by Iranian vessels, bolstering the capabilities of GCC navies could be one way to add pressure on Iran in the Gulf and perhaps reduce the U.S. burden there.

Some have argued that while the United States and its Gulf partners share many key goals and a broad desire to contain Iran, they are still independent states with disparate agendas, and that outsourcing at least some U.S. deterrence to potentially less capable partners increases the risk of instability and perhaps unintended conflict.106 Iran and some observers blame the militarization of the region on massive U.S. arms sales, which have set the stage for what some describe as a "missile race."107 Officials from Gulf states have at times complained that an "extended deterrence" framework is not practical because of what they see as burdensome bureaucratic and legal conditions on U.S. assistance.108 Some U.S. officials have echoed these concerns in supporting faster and more easily facilitated arms procurements, warning that efforts to block arms sales to countries like Saudi Arabia can be detrimental to U.S. security interests (see "Providing Weaponry to Governments Suspected of Human Rights" below).

Saudi-Led Coalition War in Yemen

Much recent congressional interest in arms sales has been influenced by the ongoing (since 2015) war in Yemen and the use of U.S.-supplied platforms and munitions by the Saudi-led coalition. The ongoing war between the Saudi-led coalition and a coalition of forces spearheaded by a group known as the Houthis has contributed to a severe humanitarian crisis in what was already the Arab world's poorest country, with millions at risk of a growing cholera epidemic and the country on the brink of famine.109 The U.N. and various nongovernmental organizations have criticized the Saudi-led coalition's bombing campaign.

The war has largely been waged with U.S.-provided weapons that members of the Saudi-led coalition already possessed when the fighting began.110 Some lawmakers have expressed concern over reports of Saudi strikes (using U.S.-supplied munitions) on civilian targets and how strikes on nonmilitary infrastructure have contributed to the humanitarian crisis.111 In an October 2017 annual report on children and armed conflict, the U.N. implicated the members of the coalition for killing and maiming children, with "510 deaths and 667 injuries attributed to the Saudi Arabia-led coalition."112

In September 2016, the Senate voted against a measure (S.J.Res. 39) that would have blocked sales of Abrams tanks and other defense equipment to Saudi Arabia, but the relatively large number of senators who sought to block the sale (27, versus 71 who sought to permit it) led some Members who backed the disapproval resolution to speculate that support for arms sales to Saudi Arabia might continue to decline.113 In June 2017, the Senate narrowly rejected (47-53) a measure (S.J.Res. 42) that would have blocked three specific sales (all notified on May 19, 2017) to Saudi Arabia of various air-delivered weapons systems, including Joint Direct Attack Munition (JDAM) kits, which convert free-fall bombs into guided (or "smart") weapons.114 Proponents of the sale argued that such technologies serve to minimize the risk of civilian casualties, defended Saudi Arabia's right to legitimate self-defense, and warned about the overall impact on U.S. efforts to combat Iranian influence, describing the Houthis as Iranian "proxies." Opponents of the sale cited a number of concerns, including Saudi Arabia's reliability as an ally, human rights concerns within the kingdom and the government's role in promoting extremism, and the sale's potential to downgrade Israel's qualitative edge, among others.115

Anticipating further sales, some Members have sought to put conditions on such transfers. Two measures (S.J.Res. 40 and H.J.Res. 104) would forbid the transfer of any air-to-ground munitions to Saudi Arabia unless the President certifies that all coalition partners are "taking all feasible precautions to reduce the risk of harm to civilians," allowing the delivery of humanitarian aid, and targeting terrorist organizations like Al Qaeda and the Islamic State as part of their operations in Yemen. In addition, the legislation would require a briefing on Saudi operations in Yemen before the transfer or notification of proposed sale of such weapons.

One legal analysis has concluded that sales of arms, especially those used in airstrikes, to Saudi Arabia "should not be presumed to be permissible" under either the AECA and/or the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 (FAA), each of which limit to whom, and for what kinds of use, the United States may sell arms.116 These limitations include prohibitions against the sale of weapons to countries that consistently violate human rights, restrict the delivery of humanitarian assistance, or use weapons in a way that differs (whether intentionally or not) from their originally agreed-upon sale.

A State Department spokesman in May 2017, when questioned about the Saudi use of U.S. weapons in Yemen, cited Saudi Arabia's right to self-defense, emphasized the provision of technical assistance on targeting, and said that the Saudis have taken steps to lessen the chance of civilian casualties and that "we're constantly trying to improve that process."117 At the same time, the issue has been raised in the United Kingdom, where, in response to a legal challenge from the Campaign Against Arms Trade, a high court ruled in July 2017 that arms exports to Saudi Arabia could continue. The court cited a "wider and more sophisticated range of information" presented (mostly in secret, on national security grounds) by the British government to justify ruling in its favor.118

Providing Weaponry to Governments Suspected of Human Rights Violations

Many Members of Congress take an interest in trying to ensure respect for human rights around the world, especially in countries that maintain close relations with the United States and over which the United States arguably has a degree of influence through its provision of arms or other services for purposes of building partner capacity (BPC).119 However, this interest has also been observed to create tension between a desire to support the rule of law and personal freedoms in various countries and the security implications of potentially harming cooperation with partner governments. At a March 2017 Senate Armed Services Committee hearing, CENTCOM Commander General Joseph L. Votel said,

[i]n recent years we have seen an increase in restrictions placed on assistance provided to partner nations, limiting their ability to acquire U.S. equipment based on human rights and/or political oppression of minority groups. While these are significant challenges that must be addressed, the use of FMF and FMS [Foreign Military Sales] as a mechanism to achieve changes in behavior has questionable effectiveness and can have unintended consequences.... We should avoid using the programs as a lever of influence or denial to our own detriment.120

This tension, typically framed as one between values and security, or as one between different types of security, often plays out in the Middle East, and arms sales are a critical part of the equation.

Bahrain has been a prominent setting for this debate. The United States has maintained a naval command in Bahrain for decades, even before the small Gulf kingdom's independence in 1971. The two nations signed a Defense Cooperation Agreement (DCA) in 1991, and President George W. Bush designated Bahrain a "major non-NATO ally" in March 2002.121 However, concerns over the Bahraini government's response to a protest movement that emerged in February 2011 have complicated the relationship. Bahrain's governing elite (dominated by minority Sunnis and led by the ruling Al Khalifa family) is accused of widespread human rights violations against the Shiite majority.122

In early 2016, Bahrain submitted a request to purchase a number of F-16s and to upgrade its existing aircraft in a deal worth as much as $4 billion. However, when the Obama Administration informally pre-notified the sale to Congress, it explained that the sale would not move forward unless Bahrain took steps toward improving its record on human rights.123 The Trump Administration dropped those conditions in March 2017, even though U.N. investigators have asserted a "sharp deterioration" of human rights over the past year in Bahrain.124 Congress was formally notified of the sale in September 2017. In his above-referenced March 2017 committee testimony, General Votel explicitly mentioned the case of Bahrain. He said that "the slow progress on key FMS cases, specifically additional F-16 aircraft and upgrades to Bahrain's existing F-16 fleet, due to concerns of potential human rights abuses in the country, continues to strain our relationship."125

Critics of the sale have argued that the Bahrain Defense Force (which largely excludes Shiites in favor of non-Bahraini Sunnis) itself contributes to instability in the country, and that the condition-free provision of U.S. weapons only exacerbates the problem.126 In the 114th Congress, legislation was introduced (H.R. 3445 and S. 2009) to prohibit the transfer of weapons that could be used for crowd control purposes, including small arms, ammunition, and Humvees, unless the State Department could certify that the government had implemented all recommendations made by the report of the government-established Bahrain Independent Commission of Inquiry (BICI).127

Egypt is another example of the challenging dynamics around human rights. In October 2013, several months after President Sisi's seizure of power, the Obama Administration announced the indefinite suspension of delivery of certain major defense articles (such as F-16s and M1A1 tanks) until the Egyptian government demonstrated progress toward democracy. The weapons suspension lasted about a year and a half, until March 2015, when President Obama allowed deliveries of certain weapons systems to proceed, while noting that future military assistance would take a different form.128

Congress, for its part, has sought to tie arms transfers to Egypt's adherence to certain democratic and human rights standards. Since FY2012, enacted appropriations measures have included language withholding certain portions of Egypt's FMF allotment unless the executive branch can certify Egypt's progress on various metrics related to human rights.129 Other than in FY2014, these measures have authorized the executive branch to waive such restrictions on national security grounds, and successive Secretaries of State have routinely exercised these waiver authorities. The FY2017 Consolidated Appropriations Act (P.L. 115-31) carried over a provision that was first included in the FY2016 appropriations act. The provision (§7041(a)) withholds 15% of Egypt's $1.3 billion FMF allocation unless the Secretary of State provides a report certifying that the Egyptian government is making progress in advancing human rights, implementing political and civil society reforms, releasing political prisoners, holding security forces responsible for alleged violations, and ensuring U.S. officials' access to monitor assistance.

In August 2017, the Trump Administration announced that while it would waive the certification requirement on national security grounds, it would withhold 15%, or $195 million, of Egypt's FMF, conditioning its eventual release on Egypt addressing various policy concerns.130 After public speculation about which policy disagreements between the United States and Egypt prompted the decision, a State Department spokeswoman stated that "it's about democracy and it's about human rights."131

Turkey, like Egypt, has attracted congressional attention for what many see as a deteriorated human rights situation. Although the United States has not provided Turkey with significant military or economic aid since the 1990s, and is not a key trading partner of Turkey, some Members of Congress have tried to limit or place conditions on arms transfers to Turkey. For example, following an incident during Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan's May 2017 visit to Washington, DC, in which members of his security detail appear to have assaulted individuals protesting near the Turkish ambassador's residence, the House passed a version of the FY2018 National Defense Authorization Act (H.R. 2810) with a "sense of Congress" provision (§1284). The provision would call for continued scrutiny of a proposed U.S. sale of handguns to Turkish presidential security personnel.132

Members of Congress may revisit existing prohibitions on the transfer of U.S. weapons to specific security force units and personnel that have engaged in human rights violations, and whether those measures are effective.133

FMF and the FY2018 Budget Request

Many U.S. arms transfers are funded through the Foreign Military Financing (FMF) account, which provides partners with assistance for the purchase of U.S. military equipment and training. These purchases are almost always processed through the Foreign Military Sales (FMS) program. FMF funds are managed by the State Department, but the program is implemented by the Department of Defense. Direct Commercial Sales (DCS) licenses are also approved by the State Department.134

President Trump's FY2018 budget request proposes to cut FMF to a number of regional governments, including Bahrain, Iraq, Lebanon, Morocco, Oman, and Tunisia, while preserving FMF for Israel (level with previous requested amounts, at $3.1 billion), Egypt (also level, at $1.3 billion), and Jordan ($350 million in FMF-Overseas Contingency Operations [OCO] funding, down from $450 million in FY2016). Those three nations make up $4.75 billion (or 93%) of the total $5.1 billion FMF request for FY2018. Pakistan is the only other identified recipient, with $100 million. Under the FY2018 proposal, the remaining $200 million would be channeled into a "global fund" to be allocated to U.S. partners around the world, with a focus on loans "where possible and appropriate."135

Some observers have questioned the wisdom of converting FMF grants to loans, arguing that such a move could weaken the U.S. defense industrial base, making weapons procurement more expensive for the United States itself, and that countries accustomed to obtaining weapons at no cost would turn to cheaper alternative providers like Russia or China.136 At least one Senator has expressed the same misgivings.137

The 2017 Consolidated Appropriations Act (P.L. 115-31) included language directing the Administration to submit a report to Congress on the budgetary, diplomatic, and foreign policy impact of a transition to more FMF loans, including its impact on FY2018 budget proposals. That report conceded that some FMF recipients may turn to other suppliers (explicitly naming China and Russia), but that the potential of such a move would be mitigated by "the high quality of defense articles and services produced by the United States compared to other suppliers."138

The report to the House State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs Appropriations bill for FY2018 (H.Rept. 115-253) notes that the bill does not include the requested authority for loan assistance on a global basis. However, the report indicates that the committee would consider providing it for individual countries, recommending that the State Department include requests for such authority (and its potential impact) in future budget justifications. The report accompanying the Senate committee bill (S.Rept. 115-152) states that the committee "does not support transitioning FMF assistance from grants to loans," noting that "prior to the submission of the CBJ no study was conducted on the impact of the proposal to U.S. national security interest or the security of stability of allies and partners, including the loss of influence through increased arms sales by the PRC [People's Republic of China] and Russia to FMF grant recipients." Members of Congress who wish to track the extent and composition of arms sales in the Middle East, or more broadly, could consider proposing other reporting requirements, including for the FMS program or for direct commercial sales (for which public information has generally been less readily available).

Table 1. Foreign Military Financing for MENA Countries: FY2016-FY2018

Current U.S. dollars in millions

|

Country |

FY2016 Obligated |

FY2017 Request |

FY2017 Enacted |

FY2018 Request |

||

|

Israel |

3,100 |

3,100 |

3,100 |

3,100 |

3,100 |

3,100 |

|

Egypt |

1,300 |

1,300 |

1,300 |

1,300 |

1,300 |

1,000 |

|

Jordan |

450 |

350 |

(authorized) |

350 |

450 |

400 |

|

Iraq |

250 |

150 |

250 |

— |

250 |

250 |

|

Lebanon |

85.9 |

105 |

(authorized) |

— |

— |

105 |

|

Tunisia |

65 |

45 |

(authorized) |

— |

65 |

65 |

|

Morocco |

10 |

5 |

(authorized) |

— |

10 |

5 |

|

Bahrain |

5 |

5 |

— |

— |

— |

5 |

|

Oman |

2 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

2 |

|

FMF Global Fund |

— |

— |

— |

200.7 |

— |

Source: State Department Congressional Budget Justifications; P.L. 115-31; P.L. 114-254.

Notes: FY2017 amounts remain subject to future allocation. The FY2018 appropriation and allocation amounts are also yet to be determined. H.R. 3362 was incorporated into House-passed H.R. 3354.

End-Use Monitoring (EUM)

Congress has long taken an interest in ensuring that arms sold to foreign countries are used responsibly and for the purposes agreed upon as part of their sale (a legal requirement for certification that goes back to the 1960s). In 1996, Congress amended the AECA to include Section 40A (P.L. 104-164), which directs the President to "establish a program that provides for end-use monitoring in order to improve accountability with respect to defense articles sold, leased, or exported under the AECA or FAA."139 The goals of end-use monitoring include preserving U.S. technological superiority by impeding adversaries' access to sensitive items and ensuring that arms are used solely by the intended recipients based on the terms under which the sale is made. In addition, as part of the standard terms and conditions of a letter of agreement (LOA), the recipient country agrees to "permit observation and review by ... representatives of the U.S. Government with regards to the use of such articles."140

End-use monitoring has been an important consideration in evaluating arms sales to Iraq, as Members of Congress try to balance the Iraqi government's need for weapons to use against the Islamic State and other threats with the potential for those arms to fall into the wrong hands, including the very groups their use is intended to combat. Since 2015, there have been widespread reports of the use of U.S. weaponry by Popular Mobilization Forces or Units (PMFs or PMUs), some of whom are supported by Iran. U.S. officials have reportedly denied the existence of any confirmed instances of Iraqi forces transferring U.S. arms to PMFs, and their Iraqi counterparts have stated that all U.S.-provided weapons remain under Iraqi army control.141 However, the challenges of tracking the whereabouts of U.S. arms are considerable in a country that has received tens of billions of dollars of weapons in the past decade alone.142

The challenges of accounting for the whereabouts of U.S. arms have perhaps grown as the United States has transferred more weapons into Iraq to help Iraqi forces confront the Islamic State. In May 2017, Amnesty International obtained (via a Freedom of Information Act request) and released a September 2016 DOD audit that determined that the Army "did not have effective controls" to track equipment transfers provided to Iraqi forces through the Iraq Train and Equip Fund (ITEF). The audit characterized the Army's recordkeeping as inconsistent, out of date, and prone to human error.143 A DOD spokeswoman stated, "The bottom line is that the US military does not have a means to track equipment that has been taken from the Government of Iraq by ISIL."144 The implications for these sales under the AECA are unclear. The DOD spokeswoman cited above explained the situation by saying that "the current conflict in Iraq limits some aspects of ... monitoring activities, including travel to many areas of Iraq and access to Iraqi units in combat areas, as well as combat use, damage and losses of war material."145

End-use monitoring is considered an important part of ensuring that recipient governments in the Middle East adhere to human rights standards. In April 2016, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) published a report that recommended "strengthening" end-use monitoring of military equipment sold to Egypt, citing the Egyptian government's failure to admit U.S. officials to storage sites and other issues.146 Similar GAO reports have been published on aid to Lebanon (February 2014)147 and GCC countries (November 2011).148 Common recommendations across these reports include

- greater coordination between the Departments of State and Defense (which operate two different EUM programs),

- more comprehensive vetting of recipients of security assistance, and

- the development of guidance (by both departments) establishing procedures for documenting end-use monitoring efforts and violations thereof.

Members of Congress may consider whether existing EUM frameworks are sufficient, and whether additional authorities, appropriations, or other legislative directives might support, streamline, or otherwise strengthen these efforts.

Appendix A. Historical U.S. Arms Sales to the Middle East, 1950-2009

All figures in millions of dollars

|

1950-1969 |

1970-1979 |

1980-1989 |

1990-1999 |

2000-2009 |

|||||||

|

Algeria |

Agreements |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Deliveries |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Bahrain |

Agreements |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Deliveries |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Egypt |

Agreements |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Deliveries |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Iran |

Agreements |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Deliveries |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Iraq |

Agreements |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Deliveries |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Israel |

Agreements |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Deliveries |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Jordan |

Agreements |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Deliveries |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Kuwait |

Agreements |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Deliveries |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Lebanon |

Agreements |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|