Introduction

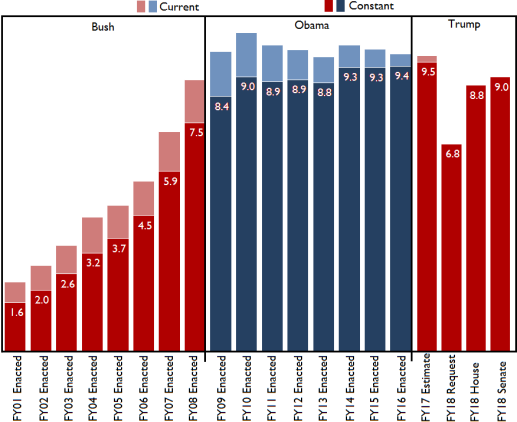

Congress has made global health a high priority for several years, with notable appropriations increases for global health during the George W. Bush Administration. During this period, global-health-related appropriations rose from less than $2 billion in FY2001 to almost $8 billion in FY2008 (Figure 1). Much of the funding increases were provided to support programs, such as the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) and the President's Malaria Initiative (PMI), that fought HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria (HTAM). Executive and legislative priorities in global health mostly aligned under the George W. Bush Administration. They largely remained so under the Obama Administration, though some debates emerged on more finite issues, such as the type of HIV/AIDS interventions to support and the extent to which the United States should support international family planning and reproductive health programs.1 It remains to be seen whether legislative and executive priorities will align under the Trump Administration.

While congressional support for global health remained steadfast throughout the Obama Administration, the great recession that began in 2008 slowed overall federal spending, and appropriations for global health programs became relatively stagnant. On average, Congress appropriated roughly $9 billion annually for global health throughout the Obama Administration.

U.S. support for global health has been motivated in large part by concern about emergent and reemerging infectious diseases. Following outbreaks of diseases like severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), HIV/AIDS, and pandemic influenza, several Presidents highlighted the threats such diseases pose to economic development, stability, and security and launched a variety of health initiatives to address them. Congress demonstrated support for each initiative by meeting requested levels, and in some instances exceeded budget proposals.

In 1996, for example, President Bill Clinton issued a presidential decision directive that called infectious diseases a threat to domestic and international security, called for U.S. global health efforts to be coordinated with those aimed at counterterrorism, and established a health advisor on the National Security Council (NSC) for the first time.2 President Clinton later requested $100 million for the Leadership and Investment in Fighting an Epidemic (LIFE) Initiative in 1999 to expand U.S. global HIV/AIDS efforts.3 President George W. Bush recognized the impact of infectious diseases on domestic and global security in his 2002 and 2006 national security strategy papers and created a number of initiatives to address them, including the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) in 2003, the President's Malaria Initiative (PMI) in 2005, and the Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTD) Program in 2006.4

President Barack Obama also recognized the risk of infectious diseases and made several statements about how their spread across developing countries might affect U.S. security.5 In the 2010 Quadrennial Diplomacy and Development Review (QDDR) and the 2010 National Security Strategy, the Obama Administration advocated for the coordination of global health programs in other areas, such as security, diplomacy and development. Rather than create an initiative aimed at infectious diseases, President Obama announced the Global Health Initiative (GHI) in 2009 to improve the coordination and impact of U.S. global health efforts. Implementation of the initiative was short-lived, though efforts to deepen integration of global health programs continued throughout the Obama Administration.

Prompted in part by the West Africa Ebola epidemic, the 115th Congress has continued deliberating approaches for strengthening weak health systems while preserving congressional priorities for key global health programs like PEPFAR. The Ebola epidemic revealed not only the threat that weak health systems in developing countries pose to the world, but also exposed gaps in international frameworks for responding to global health crises. Consensus is emerging that health system strengthening is important for protecting advancements in global health and for bolstering international security, though debate abounds regarding the appropriate approach for achieving this goal, as well as identifying the role the United States might play in such efforts, especially in relation to other U.S. global health assistance priorities.

|

|

Source: United Nations webpage on the SDGs at http://www.un.org. |

Advancements in Global Health

In 2015, the international community adopted the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to continue progress achieved through the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs).6 The SDGs include 17 goals, the third of which is health (Figure 2). Each SDG includes a set of targets to measure progress. SDG3 includes 13 targets, such as reducing child and maternal mortality; ending epidemics of key communicable diseases like HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis (TB), and malaria; and strengthening state capacity to manage national and global health risks through the achievement of universal health coverage.7 Though the international community has made considerable strides in improving global health, challenges persist. The section below summarizes some advances and challenges.

Maternal and Child Health

Intensified efforts to improve health outcomes during pregnancy and childbirth have led to a 43% reduction in the number of maternal deaths between 1990 and 2015. During this period, the number of maternal deaths fell from roughly 523,000 to an estimated 303,000, about 99% of which occurred in low- and middle-income countries.8 Sub-Saharan Africa and southern Asia were the most affected regions, accounting for 66% and 21% of all maternal deaths, respectively. Roughly one-third of all maternal deaths occurred in Nigeria and India.

Human resource constraints continue to complicate efforts to reduce maternal mortality. In many developing countries, pregnant women deliver their babies without the assistance of trained health practitioners who can help to avert deaths caused by hemorrhage—the leading cause of direct maternal death. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 27% of all maternal deaths are caused by severe bleeding. Preexisting conditions like HIV/AIDS and malaria are also key contributors to maternal mortality, accounting for roughly 28% of maternal deaths combined.

From 1990 to 2015, the number of child deaths fell from 12.7 million to 5.9 million.9 WHO estimates that more than half of the 16,000 child deaths that occurred in each day of 2015 could have been avoided through low-cost interventions, such as medicines to treat pneumonia, diarrhea, and malaria, as well as tools to prevent the transmission of malaria and HIV/AIDS from mother to child.10 Other factors, like inadequate access to nutritious food, also affect child health. WHO estimates that undernutrition contributes to roughly 45% of all child deaths.11 The risk of a child dying is at its highest within the first month of life, when 45% of all child deaths occur. Children in sub-Saharan Africa are more than 14 times more likely to die before reaching age five than their counterparts in developed countries.

HIV/AIDS

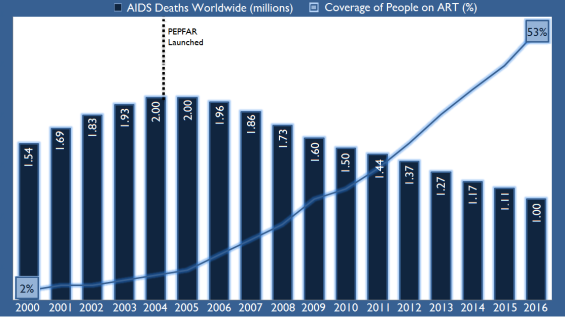

At the end of 2016, almost 37 million people were living with HIV worldwide, nearly 2 million of whom contracted the disease in that year and more than 60% of whom lived in sub-Saharan Africa.12 In 2016, 1 million people died of AIDS, down from 1.9 million in 2003 (before the start of PEPFAR; see Figure 3).

|

|

Source: Created by CRS from the UNAIDS database at http://aidsinfo.unaids.org/. |

Expanded access to anti-retroviral treatments (ARTs) has decreased the number of AIDS deaths. Roughly 53% of HIV-positive people worldwide were on ART in 2016, up from 4% in 2003. The United States has contributed substantially to improving global access to ART through PEPFAR and its support for the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (Global Fund). An estimated 19.5 million people worldwide were on ART at the end of 2016. The Office of the Global AIDS Coordinator (OGAC) indicated that by 2016 the United States was supporting ART for almost 11.5 million people worldwide through PEPFAR programs and U.S. contributions to the Global Fund.13

Other Infectious Diseases

In recent years, a succession of new and reemerging infectious diseases have caused outbreaks and pandemics that have affected thousands of people worldwide: Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS, 2003), Avian Influenza H5N1 (2005), Pandemic Influenza H1N1 (2009), Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV, 2013), Ebola in West Africa (2014-2016), the Zika virus (2015-2016), and Yellow Fever in Central Africa (2016) and South America (2016-2017). The United States has played a leading role in launching and implementing the Global Health Security Agenda, a multilateral effort to improve the capacity of countries worldwide to detect, prevent, and respond to diseases with pandemic potential.

While the world faces threats from new diseases, long-standing diseases like tuberculosis (TB) also pose a threat to global health security. Among infectious diseases, TB is the most common cause of death worldwide. Multi-drug resistant (MDR)-TB is of growing concern, as it is more expensive and difficult to treat. Only half of all MDR-TB patients survive.14 WHO asserts that global funding for addressing MDR-TB is insufficient and weaknesses in health systems complicate efforts to treat the disease and prevent its further spread.

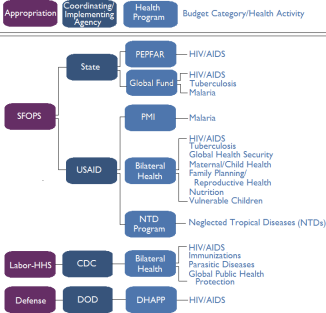

Appropriations for U.S. Global Health Programs

Congress funds most global health assistance through two appropriations bills: State-Foreign Operations and Related Programs (SFOPS) and Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education (Labor-HHS; see Figure 4). These bills are used to fund global health efforts implemented by USAID and the U.S. Centers for Defense Control and Prevention (CDC), as well as PEPFAR programs that are coordinated by the Department of State and implemented by several U.S. agencies. Through PEPFAR, the United States contributes to multilateral efforts to combat HIV/AIDS, TB, and malaria (HATM), including the Global Fund and the Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS).

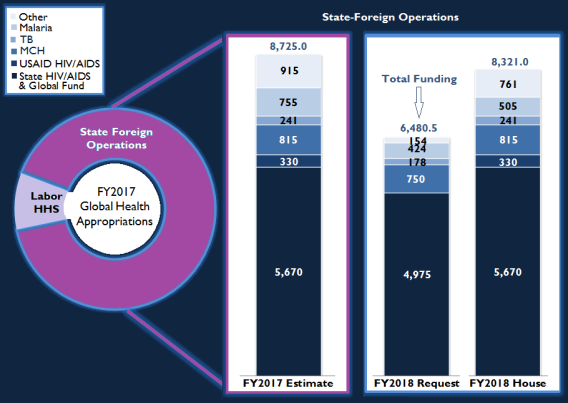

State-Foreign Operations Appropriations

The majority of appropriations for global health programs are provided through the Global Health Programs Account (GHP) in State-Foreign Operations appropriations (Figure 5). More than 80% of the funds are used for fighting HATM through bilateral programs and the Global Fund. Table A-2 outlines global health funding through State-Foreign Operations.

Labor-HHS Appropriations

Through Labor-HHS appropriations, Congress funds global health programs implemented by CDC and global HIV/AIDS research conducted by the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Labor-HHS appropriations do not specify an amount for NIH global HIV/AIDS research, though the Administration typically includes these amounts in reports on PEPFAR funding. Table A-3 outlines global health spending through Labor-HHS.

Implementing Agencies and Departments

This section describes the global health activities implemented or coordinated by each agency that received appropriations, as described above. This discussion is limited to those agencies and departments for which Congress provides funding specifically for global health: USAID, State, and CDC. Agencies may use internal funding to contribute to additional global health efforts.

U.S. Agency for International Development15

USAID groups its global health activities into three areas: saving mothers and children, creating an AIDS-Free generation, and fighting other infectious diseases. A summary of these efforts is described below.

- Saving Mothers and Children. USAID seeks to save the lives of women and children by reducing morbidity and mortality from vaccine-preventable deaths, malaria, and undernutrition; supporting vulnerable children and orphans; and increasing access to family planning and reproductive health services.

- Creating an AIDS-Free Generation. USAID aims to combat HIV/AIDS by supporting voluntary counseling and testing, awareness campaigns, and the supply of antiretroviral medicines, among other activities.

- Fighting Other Infectious Diseases. USAID works to address a number of infectious diseases and resultant outbreaks. Congress appropriates a specific amount for malaria, TB, NTDs, pandemic influenza and other emerging threats.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention16

Through Labor-HHS appropriations, Congress specifies support for the following CDC global health activities:

- HIV/AIDS. CDC works with Ministries of Health (MOHs) and global partners to increase access to integrated HIV/AIDS care and treatment services, strengthen and expand high-quality laboratory services, conduct research, and support resource-constrained countries' efforts to develop sustainable public health systems.

- Parasitic Diseases and Malaria. CDC aims to reduce death and illness associated with parasitic diseases, including malaria, by capacity building and enhancing surveillance, monitoring and evaluation, vector control, case management, and diagnostic testing. CDC also identifies best practices for parasitic disease programs and conducts epidemiological and laboratory research for the development of new tools and strategies.

- Global Immunization. CDC works to advance several global immunization initiatives aimed at preventable diseases, including polio, measles, rubella, and meningitis; accelerate the introduction of new vaccines; and strengthen immunization systems in priority countries through technical assistance, monitoring and evaluation, social mobilization, and vaccine management.

- Global Public Health Capacity Development. CDC helps MOHs develop Field Epidemiology Training Programs (FETPs) that strengthen health systems by enhancing laboratory management, applied research, communications, program evaluation, program management, and disease detection and response. Through the Global Disease Detection (GDD) program, CDC builds capacity to monitor, detect, and assess disease threats and responds to requests from other U.S. agencies, United Nations agencies, and nongovernmental organizations for support in humanitarian assistance activities.

Department of State

Through OGAC, the State Department leads PEPFAR and oversees all U.S. spending on global HIV/AIDS, including those appropriated to other agencies and multilateral groups like the Global Fund and UNAIDS. In July 2012, the Obama Administration announced an expansion of the State Department's engagement in global health with the launch of the Office of Global Health Diplomacy (OGHD).17 The office seeks to "guide diplomatic efforts to advance the United States' global health mission" and provide "diplomatic support in implementing the Global Health Initiative's principles and goals."18 The Global AIDS Coordinator also leads OGHD. The key objectives of the OGHD are to

- provide ambassadors with expertise, support, and tools to help them effectively work with country officials on global health issues;

- elevate the role of ambassadors in their efforts to pursue diplomatic strategies and partnerships within countries to advance health;

- support ambassadors to build political will among partner countries to improve health and strengthen health systems;

- strengthen the sustainability of health programs by helping partner countries meet the health care needs of their own people and achieve country ownership; and

- foster shared responsibility and coordination among donor nations, multilateral institutions, civil society, the private sector, faith-based organizations, foundations, and community members.

Department of Defense

The Department of Defense (DOD) carries out a wide range of health activities abroad, including infectious disease research, health assistance following natural disasters and other emergencies, and training of foreign health workers and officials.19 The DOD HIV/AIDS Prevention Program (DHAPP) is the only global health program for which Congress has appropriated funds to the department for any global health activity. As an implementing agency of PEPFAR, DOD also receives transfers from the Department of State for HIV/AIDS research, care, treatment, and prevention programs.20 Table A-3 in the Appendix outlines annual funding for DHAAP.

Presidential Health Initiatives

The bulk of U.S. global health appropriations is provided for health initiatives established under the George W. Bush Administration. A brief discussion of these efforts follows.

President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR)21

In January 2003, President George W. Bush announced PEPFAR, a government-wide initiative to combat global HIV/AIDS. Later that year, Congress enacted the Leadership Act (P.L. 108-25), which authorized $15 billion to be spent from FY2004 to FY2008 on bilateral and multilateral HIV/AIDS, TB, and malaria programs and authorized the creation of OGAC to oversee all U.S. spending on global HIV/AIDS. OGAC distributes the majority of the funds it receives from Congress for bilateral HIV/AIDS programs and multilateral efforts, like those carried out by the Global Fund.

In 2008, Congress enacted the Lantos-Hyde Act (P.L. 110-293), which among other things amended the Leadership Act to authorize the appropriation of $48 billion for global HIV/AIDS, TB, and malaria efforts from FY2009 to FY2013. In November 2013, Congress enacted P.L. 113-56, the PEPFAR Stewardship and Oversight Act.22 The act did not authorize a specific amount of funds for the program, though it continues to receive bipartisan support.

President's Malaria Initiative (PMI)23

In June 2005, President George W. Bush announced PMI to expand and coordinate U.S. global malaria efforts. PMI was originally established as a five-year, $1.2 billion effort to halve the number of malaria-related deaths in 15 sub-Saharan African countries through the expansion of four prevention and treatment techniques: indoor residual spraying (IRS), insecticide-treated nets (ITNs), artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs), and intermittent preventive treatment for pregnant women (IPTp).24 The Obama Administration expanded the goals of PMI to halving the burden of malaria among 70% of at-risk populations in Africa by 2014 and added the Democratic Republic of Congo, Guinea, Nigeria, and Zimbabwe as partner countries.

The Leadership Act, as amended, authorized the establishment of the U.S. Malaria Coordinator at USAID. The Malaria Coordinator oversees implementation efforts of USAID and CDC and is advised by an Interagency Advisory Group that includes representatives from USAID, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), State, DOD, the National Security Council (NSC), and the Office of Management and Budget (OMB).

Neglected Tropical Disease (NTD) Program25

The NTD Program started in 2006, following language in FY2006 State-Foreign Operations appropriations that directed USAID to make available at least $15 million for fighting seven NTDs.26 It is managed by USAID and jointly implemented by USAID and CDC. When the program was launched, the George W. Bush Administration sought to support the provision of 160 million NTD treatments for 40 million people in 15 countries. In 2008, President Bush reaffirmed his commitment to tackling NTDs and proposed spending $350 million from FY2008 through FY2013 on expanding the program to 30 countries. In 2009, the Obama Administration amended the targets of the NTD program and called for the United States to support halving the prevalence of NTDs among 70% of the affected population in target countries.

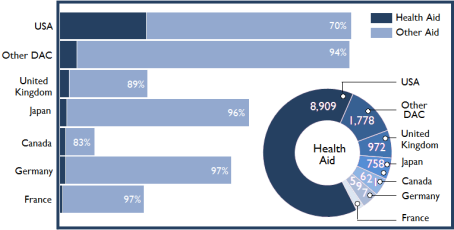

Global Health Spending by Other Countries

The United States provides more official development assistance (ODA) for health than any other country in the Development Assistance Committee (DAC).27 In 2015, U.S. spending on global health accounted for more than 60% of all health aid provided by DAC members (Figure 6). The United States also apportions more of its foreign aid to improving global health than most other donor countries. As illustrated in Figure 6, Canada allots the second-largest share (17%) of its ODA to health assistance.

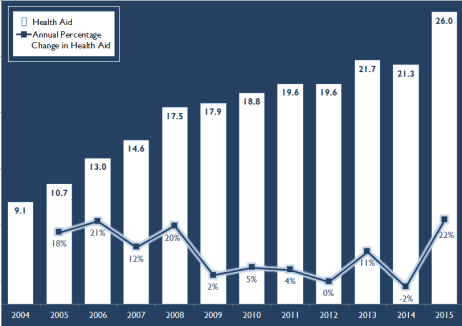

Funding for global health assistance has grown over the past decade (Figure 7). Between 2004 and 2015, DAC countries and other donors tripled their support for global health aid. Development assistance for health grew most robustly from 2004 through 2008 and increased at a slower pace thereafter. Nonetheless, donor support for global health has remained firm and has been primarily aimed at addressing key ailments like HIV/AIDS.

|

Figure 7. Official Development Assistance for Health, FY2004-FY2015 (2015 constant U.S. $ billions and annual percent change) |

|

|

Source: Created by CRS from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) website on statistics at http://www.oecd.org/statistics/, accessed on June 22, 2017. |

Issues for the 115th Congress

The international community has been committed to improving global health for decades, and the United States has played a leading role in these efforts. Related efforts have vacillated between improving primary health systems and focusing on particular health issues. In the 1970s and 1980s, for example, the international community sought to ensure "an acceptable level of health for all the people of the world by the year 2000" through bolstering primary health systems.28 While advances were made, some global health experts asserted that weak health systems impeded efforts to improve health outcomes and began to advocate for targeting heath assistance through nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) rather than host governments. Supporters of targeted health assistance asserted that vertical programs facilitate monitoring and evaluation of impact and directly funding NGOs lessens the likelihood that health assistance will be wasted or diverted. Opponents argued that disease-specific programs exacerbate human resource shortages in the public sector and further weaken health systems when parallel bureaucracies are established and government authorities are circumvented. The international community agreed in 2000 to a targeted approach and galvanized around the Millennium Development Goals. While progress was made on achieving the MDGs, the health-related goals were not completely met. Many donors and partner countries have come to agree that progress made by disease-specific programs is being undermined by weak health systems and could erode if health systems are not buttressed. The international community agreed to apply lessons learned from addressing priority health concerns to strengthening primary health care systems over the next 15 years through the Sustainable Development Goals.

Congressional support for global health assistance has primarily focused on specific health conditions, especially HIV/AIDS. Recent disease outbreaks have intensified discussions about boosting global capacity to prevent, respond to, and control epidemics through strengthened health systems. Following the Ebola outbreak, Congress provided CDC almost $600 million for the Global Health Security Agenda through P.L. 113-235, the Consolidated and Further Continuing Appropriations Act, 2015. No additional funds have been provided for pandemic preparedness since then; however, regular appropriations for related programs through USAID and CDC have mostly remained flat since then. In addition, congressional deliberations about strengthening health systems have intensified, though no legislation has been introduced on the subject. The section below highlights key issues of possible concern.

FY2018 Budget

The FY2018 budget request includes nearly $7 billion for global health assistance, roughly 26% less than what was provided in FY2017 for global health programs through SFOPS and some 19% less for global health programs managed by CDC (Table 1). The Trump Administration proposes halving the USAID global health budget by eliminating funding for global health security, vulnerable children, and family planning and reproductive health and by reducing support for all other programs. The Trump Administration indicated that "other stakeholders must do more to contribute their fair share to global health initiatives."29 For detailed information on the State-Foreign Operations appropriations budget request and prior funding levels, see Table A-2 in the Appendix.

In addition to the State-Foreign Operations appropriations cuts, the Administration is seeking an 18% reduction for programs implemented by CDC through the Labor-HHS appropriations. The bulk of the budgetary cuts is aimed at HIV/AIDS (-85%), measles (-22%), and global disease detection programs (-10%). It is unclear how proposed budget cuts might affect U.S. efforts to prevent and respond to global disease outbreaks, though CDC indicated in its FY2018 Congressional Budget Justification that the size of and frequency at which Global Rapid Response Teams can be deployed will be reduced. For additional information on the Labor-HHS appropriations, see Table A-3.

|

FY2014 Enacted |

FY2015 Enacted |

FY2016 Enacted |

FY2017 Estimate |

FY2018 Request |

FY2017-FY2018 |

FY2018 House |

FY2018 Senate |

||||||||

|

State-GHP |

4,020.0 |

4,320.0 |

4,320.0 |

4,320.0 |

3,850.0 |

-11% |

4,320.0 |

4,320.0 |

|||||||

|

USAID-GHP |

2,775.3 |

2,784.0 |

2,833.5 |

2985.0 |

1,505.5 |

-51% |

2,651.0 |

2,920.0 |

|||||||

|

Global Fund |

1,650.0 |

1,350.0 |

1,350.0 |

1,350.0 |

1,125.0 |

-17% |

1,350.0 |

1,350.0 |

|||||||

|

SFOPS Total |

8,445.3 |

8,454.0 |

8,503.5 |

8,655.0 |

6,480.5 |

-26% |

8,321.0 |

8,590.0 |

|||||||

|

SFOPS Ebola Emergency |

0.0 |

632.3 |

0.0 |

70.0 |

322.5a |

n/a |

322.5b |

120.0c |

|||||||

|

SFOPS Zika Emergency |

0.0 |

0.0 |

145.5 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

n/a |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|||||||

|

SFOPS Total Inc. Emergency Approps. |

8,445.3 |

9,086.3 |

8,649.0 |

8,725.0 |

6,803.0 |

n/a |

8,643.5 |

8,710.0 |

|||||||

|

CDC |

416.8 |

416.5 |

426.6 |

426.4 |

349.9 |

-19% |

435.1 |

433.6 |

|||||||

|

NIH Global AIDS Research |

453.6 |

433.8 |

431.1 |

431.9 |

d |

d |

d |

d |

|||||||

|

Labor-HHS Total |

870.4 |

850.3 |

857.7 |

858.3 |

d |

d |

d |

d |

|||||||

|

Labor-HHS Ebola Emergency |

0.0 |

1,194.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|||||||

|

Labor-HHS Zika Emergency |

0.0 |

0.0 |

394.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|||||||

|

Labor-HHS Total Inc. Emergency Approps. |

870.4 |

2,044.3 |

1,251.7 |

858.3 |

e |

e |

e |

e |

|||||||

|

DOD |

8.0 |

8.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

f |

f |

f |

f |

|||||||

|

Total Global Health |

9,323.7 |

9,312.3 |

9,361.2 |

9,513.3 |

e |

e |

e |

e |

|||||||

|

Total Global Health, Inc. Emergency Appropriations |

9,323.7 |

11,138.6 |

9,900.7 |

9,583.3 |

e |

e |

e |

e |

|||||||

Source: Created by CRS from congressional budget justifications and correspondence with USAID and CDC legislative affairs offices.

Abbreviations: Global Health Programs (GHP), United States Agency for International Development (USAID), State Foreign Operations Appropriations (SFOPS) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Institutes of Health (NIH), Department of Labor, HHS, and Education Appropriations (Labor-HHS), Appropriations (Approps.), not applicable (n/a).

Notes: Excludes emergency appropriations for international responses to Ebola and Zika outbreaks.

a. The Administration proposes transferring $322.5 million of unobligated funds provided for the Ebola outbreak to USAID for malaria ($250 million) and other global health security ($72.5 million).

b. The House Appropriations Committee recommended transferring $322.5 million of unobligated funds provided for the Ebola outbreak, though it did not specify how all of these funds should be used.

c. The Senate Appropriations Committee recommended transferring $120 million of unobligated funds provided for the Ebola outbreak to support USAID activities aimed at addressing malaria ($100 million) and tuberculosis ($20 million).

d. The Administration did not request a particular amount for NIH international HIV/AIDS research. Amounts that the Administration spends on NIH international HIV/AIDS research is drawn from the overall budget of the Office of AIDS Research. Those amounts are reported annually in congressional budget justifications.

e. To maintain consistency across fiscal years, CRS did not aggregate the total since information is not yet available on the amounts NIH anticipates spending on international HIV/AIDS research.

f. The Department of Defense has not requested funds for global HIV/AIDS programs for several fiscal years, though the department continues to receive funds for HIV prevention activities through PEPFAR.

Coordinating U.S. Government Global Health Programs

In FY2017, Congress provided roughly $9.6 billion for global health programs. More than 70% of those funds were appropriated to the State Department for the coordination and oversight of bilateral HIV/AIDS programs through PEPFAR and for a $1.3 billion contribution to the Global Fund. At the same time, USAID coordinates and implements global health programs that amount to roughly 30% of U.S. spending on global health. HHS, including CDC, also plays a growing role in global health through its leadership in the Global Health Security Agenda, as well as the National Public Health Institutes. During the first term of the Obama Administration, President Obama announced the Global Health Initiative to improve the coordination and integration of U.S. bilateral global health programs. That initiative is largely defunct and questions remain about whether U.S. global health programs are sufficiently coordinated during the planning and implementation phase and how such programs (which are mostly disease-specific) might be leveraged to strengthen health systems. Efforts by the Trump Administration to reorganize the State Department and USAID are underway. It is unclear the extent to which such activities might impact the coordination of U.S. bilateral health initiatives.

Addressing Calls for Strengthening Health Systems

As discussed earlier, the international community has made significant strides in addressing key health issues, like maternal and child health, through targeted assistance. The Ebola epidemic has demonstrated some deficiencies in this approach and has prompted calls for investing "diagonally" in both vertical and "horizontal" health systems-based programs. According to WHO, there are six components of a health system:

- Human resources. The people who provide health care and support health delivery.

- Governance and leadership. Policies, strategies, and plans that countries employ to guide health programs.

- Financing. Mechanisms used to fund health efforts and allocate resources.

- Commodities. Goods that are used to provide health care.

- Service delivery. The management and delivery of health care.

- Information. The collection, analysis, and dissemination of health statistics for planning and allocating health resources.

Consensus is emerging that health system strengthening is important for achieving global health objectives and ensuring international security, though experts debate the appropriate approach for achieving this goal and the role the United States should play in such efforts, especially in relation to other U.S. global health assistance priorities. Supporters of health system strengthening argue that systems-based funding is cost-efficient because it can reduce redundancies, boost country ownership, and could ultimately eliminate the need for funding vertical programs. On the other hand, some groups caution that a global framework needs to be developed that would identify indicators for measuring the impact of health systems programs, coordinating such efforts, and overseeing related resources.

The Growing Role of Nonstate Actors

The global health funding system is becoming increasingly diverse as a variety of new actors become involved, particularly nonstate actors like the private sector and private foundations. In 2015, for example, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation spent more on global health than all DAC countries except the United States. Specifically, the OECD reported that in 2015, the Gates Foundation spent approximately $2.7 billion on global health, almost $2 billion more than United Kingdom, the country that provided the second-largest amount of health aid.30

Global health experts are debating how the burgeoning number of players might affect global health effectiveness in general and U.S. influence in this realm in particular.31 The growth of actors in the global health sector raises several questions:

- How might U.S. influence be affected by the growing number of global health actors, particularly in its efforts to encourage countries to take greater ownership of their health programs?

- How might the United States effectively engage with nonstate actors to encourage donor engagement, avoid duplication of resources, and improve the sustainability of U.S. investments?

- How might the United States maintain its accountability and transparency standards should it choose to deepen collaboration with other players?

The appropriate balance between bilateral and multilateral assistance is a frequent point of contention among U.S. policymakers. This debate has intensified in recent years, and some question the extent to which the Trump Administration will engage with multilateral actors. The United States is a leading contributor to several multilateral health organizations, including the Global Fund, UNAIDS, WHO, the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative (IAVI), and the GAVI Alliance, among others.

Proponents of strong bilateral funding argue that direct U.S. global health spending carries a number of advantages, including improved capacity to

- direct where and how aid is used,

- monitor and evaluate use of aid and program impact, and

- adjust how funds are spent.

On the other hand, some observers maintain U.S. participation in multilateral responses to global health offers distinct advantages, including the ability to

- pool and leverage limited resources, which can capitalize on efficiencies;

- coordinate assistance with a range of donors; and

- engage with countries with whom the United States may not have close relations.

Reducing waste and inefficiencies are critical components of discussions regarding funding bilateral and multilateral health programs. According to a report by WHO, 20% to 40% of health spending is wasted through inefficiency.32 The report identified several areas in which donors could eliminate waste, namely through aligning financial, reporting, and monitoring practices. By harmonizing the auditing, monitoring, and evaluation of bilateral and multilateral programs, WHO asserted, health staff could use some of the time spent on compiling reports to address other health issues.

Outlook

Despite ongoing debates about the utility of foreign assistance, global health programs have, in general, continued to receive bipartisan support. Some expect that global health will remain a congressional priority. While the international community has achieved significant gains in curbing preventable deaths, some experts are concerned about looming health challenges. In a growing number of countries, deaths and illness from noncommunicable diseases (like diabetes, cancer, and heart disease) are outnumbering fatalities and ailments from communicable diseases (like malaria and HIV/AIDS). Many middle-income countries like South Africa face dual epidemics of diseases associated with growing prosperity (diabetes) and persistent poverty (vaccine-preventable child deaths). In the absence of higher spending levels, bolstering health systems will likely gain greater importance in U.S. global health programs.

Along with debating issues related to U.S. global health assistance, Congress may consider its own role in U.S. global health aid policy. Congress has exercised growing involvement in shaping global health programs by authorizing the creation of key global health positions, enacting legislation that included spending directives and described congressional priorities. Global health analysts have debated whether Congress's elevated role has helped or hindered the efficacy of global health programs. For example, some argue that congressional spending directives have limited the ability of country teams to tailor programs to in-country needs. Others argue that congressional mandates and recommendations have protected critical areas in need of support and facilitated the implementation of a cohesive global health strategy across agencies.

Appendix. Global Health Funding Tables, by Agency and Appropriation Vehicle

Table A-1. U.S. Global Health Funding, by Agency and Appropriation Vehicle: FY2001-FY2018 Request

(current U.S. $ millions)

|

Agency/Program |

Bush Administration |

Obama Administration |

Trump Administration |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

FY2001-FY2008 Total |

FY2001-FY2008 Average |

FY2009-FY2016 Total |

FY2009-FY2016 Average |

FY2017 Estimate |

FY2018 Request |

FY2018 House |

FY2018 Senate |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

State HIV/AIDS |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Global Fund |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

USAID |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

SFOPS Total |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

SFOPS Ebola Emergency |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

120.0c |

||||||||||||||||||

|

SFOPS Zika Emergency |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.0 |

||||||||||||||||||

|

SFOPS Total, Including Emergency Appropriations |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

8,710.0 |

||||||||||||||||||

|

CDC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

NIH Global AIDS Research |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Global Funde |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

DOL HIV/AIDSf |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Labor-HHS Total |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Labor-HHS Ebola Emergency |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Labor-HHS Zika Emergency |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Labor-HHS Total, Including Emergency Appropriations |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

DOD HIV/AIDSh |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Total Global Health |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Total Global Health, Including Emergency Appropriations |

|

|

|

|

9,583.3 |

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

Source: Created by CRS from appropriations legislation and correspondence with CDC and USAID legislative affairs offices.

Notes: U.S. Department of State (State), Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria (Global Fund), U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs Appropriations (SFOPS), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Institutes of Health (NIH), U.S. Department of Labor (DOL), Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Appropriations (Labor-HHS), U.S. Department of Defense (DOD), not specified (n/s).

Figures in FY2001-2008 include funds appropriated to multiple accounts within State-Foreign Operations. Figures in FY2009-FY2014 only include appropriations to the Global Health Programs account. Additional resources that CDC may provide for global health programs through other accounts are not included here. CDC, for example, spends a portion of its tuberculosis budget on global activities.

a. The Administration proposes transferring $322.5 million of unobligated funds provided for the Ebola outbreak to USAID for malaria ($250 million) and other global health security ($72.5 million).

b. The House Appropriations Committee recommended transferring $322.5 million of unobligated funds provided for the Ebola outbreak, though it did not specify how all of these funds should be used.

c. The Senate Appropriations Committee recommended transferring $120 million of unobligated funds provided for the Ebola outbreak to support USAID activities aimed at addressing malaria ($100 million) and tuberculosis ($20 million).

d. The Administration did not request a particular amount for NIH international HIV/AIDS research. Amounts that the Administration spends on NIH international HIV/AIDS research is drawn from the overall budget of the Office of AIDS Research. Those amounts are reported annually in congressional budget justifications.

e. From FY2001 through FY2011, Congress provided funds for U.S. contributions to the Global Fund through SFOPS and Labor-HHS appropriations. After then, Congress provided all funds for U.S. Global Fund contributions to the State Department.

f. Congress appropriated funds to the Department of Labor for global HIV/AIDS activities from FY2001 through FY2005. After then, all support for DOL HIV/AIDS activities were provided through appropriations to the State Department.

g. To maintain consistency across fiscal years, CRS did not aggregate the total since FY2018 requested levels for NIH research are not yet available.

h. Congress appropriated funds to the Department of Defense for global HIV/AIDS activities from FY2001 through FY2015. After then, all support for DOD HIV/AIDS activities were provided through appropriations to the State Department.

Table A-2. Global Health State-Foreign Operations Funding: FY2001-2018 Request

(current U.S. $ millions)

|

Agency/Program |

Bush Administration |

Obama Administration |

Trump Administration |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

FY2001-FY2008 Total |

FY2001-FY2008 Average |

FY2009-FY2016 Total |

FY2009-FY2016 Average |

FY2017 Estimate |

FY2018 Request |

FY2018 House |

FY2018 Senate |

|||||||||||||||||

|

HIV/AIDS |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Global Fund |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

State Total |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

HIVAIDS |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Global Fund |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Tuberculosis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Malaria |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Maternal and Child Health |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Nutritionb |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Vulnerable Children |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Family Planning/Rep. Health |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Neglected Tropical Diseases |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Pandemic Influenza/Other |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

USAID Total |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

SFOPS Total |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Ebola Emergencyc |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Zika Emergency |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

SFOPS Total, Including Emergency Appropriations |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

Source: Appropriations legislation, congressional budget justifications, and personal communication with USAID Office of Legislative Affairs.

Notes: Reproductive Health (Rep. Health), U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), State, Foreign Operations (SFOPS), not specified (n/s). Figures in FY2001-2008 include funds appropriated to multiple accounts within State-Foreign Operations. Figures in FY2009-FY2014 only include appropriations to the Global Health Programs Account.

a. The House Appropriations Committee recommended including $132.5 million for a contribution to the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) within the $2,651.0 million it recommended providing for USAID global health programs. This amount is included in the maternal and child health subcategory above.

b. Congress began to appropriate funds for nutrition in 2009. Until then, nutrition funds were included in appropriations for maternal and child health programs.

c. Includes amounts provided directly for emergency Ebola operations, as well as amounts to be transferred from unobligated emergency Ebola funds.

d. The Administration proposed transferring $322.5 million of unobligated funds provided for the Ebola outbreak to USAID for malaria ($250 million) and other global health security ($72.5 million).

e. The House Appropriations Committee recommended transferring $322.5 million of unobligated funds provided for the Ebola outbreak. It did not specify how all of these funds should be used, though it did specify that $10.0 million would be drawn from these amounts to advance USAID global health security efforts.

f. The Senate Appropriations Committee recommended transferring $120 million of unobligated funds provided for the Ebola outbreak to support USAID activities aimed at addressing malaria ($100 million) and tuberculosis ($20 million).

|

Agency/Program |

Bush Administration |

Obama Administration |

Trump Administration |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

FY2001-FY2008 Total |

FY2001-FY2008 Average |

FY2009-FY2016 Total |

FY2009-FY2016 Average |

FY2017 Estimate |

FY2018 Request |

FY2018 House |

FY2018 Senate |

|||||||||||||||||

|

HIV/AIDS |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Immunizations |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Polio |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Other Global/Measles |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Parasitic Diseases/Malariaa |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Malaria |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Global Public Health Protection |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Global Disease Detection |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Public Health Capacity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

CDC Total |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

NIH Global AIDS Research |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

HHS Global Fund |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

DOL |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Labor-HHS Total |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Ebola Emergency |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Zika Emergency |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Labor-HHS Total, Including Emergency Appropriations |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

Source: Appropriations legislation, congressional budget justifications, and personal communication with CDC Office of Legislative Affairs.

Notes: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Institutes of Health (NIH), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Department of Labor (Labor), not applicable, not specified (n/s).

a. In the FY2012 Congressional Budget Justification, the Administration proposed creating a new line item, Parasitic Diseases/Malaria, that combined funding for programs aimed at addressing parasitic diseases (like neglected tropical diseases) with those aimed at combating malaria.

b. The Administration did not request a particular amount for NIH international HIV/AIDS research. Amounts that the Administration spends on NIH international HIV/AIDS research is drawn from the overall budget of the Office of AIDS Research. Those amounts are reported annually in congressional budget justifications.

c. To maintain consistency across fiscal years, CRS did not aggregate the total since FY2018 requested levels for NIH research are not yet available.

|

Agency/Program |

Bush Administration |

Obama Administration |

Trump Administration |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

FY2001-FY2008 Total |

FY2001-FY2008 Average |

FY2009-FY2016 Total |

FY2009-FY2016 Average |

FY2017 Estimate |

FY2018 Request |

FY2018 House |

FY2018 Senate |

|||||||||||||||||

|

State |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Global Fund |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

USAID |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

SFOPS HIV/AIDS Total |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

CDC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

NIHb |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Global Fund |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

DOL |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Labor-HHS HIV/AIDS Total |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

DOD |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

U.S. Global HIV/AIDS Total |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Total Global Fund |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

Source: Appropriations legislation, congressional budget justifications, and personal communication with USAID and CDC legislative affairs offices.

Notes: Rows in bold are included within totals of the preceding rows.

a. The House Appropriations Committee recommended that $6.0 billion be provided for global HIV/AIDS programs through State-Foreign Operations appropriations. The Committee report specified that $5.67 billion should be provided to the State Department for global HIV/AIDS programs, including $1.35 billion for a U.S. contribution to the multilateral Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria.

b. The Administration did not request a particular amount for NIH international HIV/AIDS research. Amounts that the Administration spends on NIH international HIV/AIDS research is drawn from the overall budget of the Office of AIDS Research. Those amounts are reported annually in congressional budget justifications.

c. To maintain consistency across fiscal years, CRS did not aggregate the total since FY2018 requested levels for NIH research are not yet available.