Introduction

This report examines trends in the timing and size of homeland security appropriations measures.

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) was officially established on January 24, 2003. Just over a week later, on February 3, 2003, the Administration made its first annual appropriations request for the new department.1 Transfers of most of the department's personnel and resources from their existing agencies to DHS occurred March 1, 2003, and on April 16, the department received its first supplemental appropriations.

March 1, 2003, fell in the middle of fiscal year 2003 (FY2003). It was not the end of a fiscal quarter. It was not even the end of a pay period for the employees transferred to the department. Despite these managerial complications, resources and employees were transferred to the control of the department and their work continued without interruption in the face of the perceived terror threat against the United States. Thus, since the department did receive appropriations and operate in FY2003, tracking the size and timing of annual appropriations for the Department of Homeland Security begins with its first annual appropriations cycle, covering FY2004.

DHS Appropriations Trends: Timing

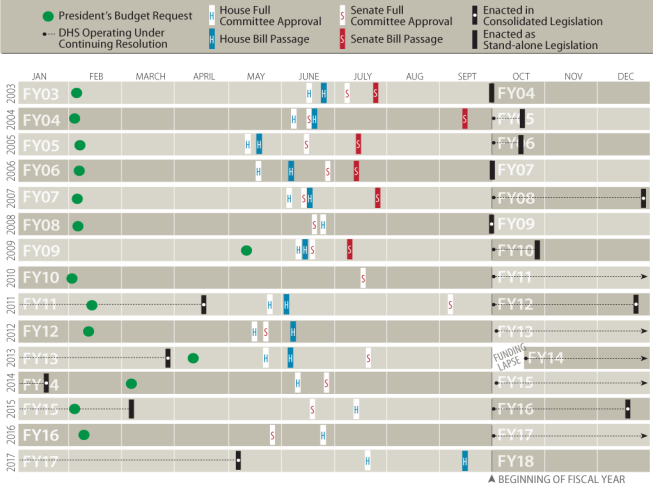

Figure 1 shows the history of the timing of the annual DHS appropriations bills as they have moved through various stages of the legislative process. Initially, DHS appropriations were enacted relatively promptly, as stand-alone legislation. However, the bill is no longer an outlier from the consolidation and delayed timing that has affected other annual appropriations legislation. FY2017 marked the latest finalization of DHS annual appropriations levels in the history of the DHS Appropriations Act.

When annual appropriations for part of the government are not enacted prior to the beginning of the fiscal year, a continuing resolution is usually enacted to provide stopgap funding and allow operations to continue. As Figure 1 shows, at the beginning of FY2014, for the first time in the history of the department, neither annual appropriations nor a continuing resolution had been enacted by the start of the fiscal year. Annual appropriations lapsed, leading to a partial shutdown of government operations, including DHS.2

|

Figure 1. DHS Appropriations Legislative Timing, FY2004-FY2018 |

|

|

Source: Analysis of presidential budget request release dates and legislative action from the Legislative Information System (LIS) available at http://www.congress.gov. Notes: Final action on the annual appropriations for DHS for FY2011, FY2013, FY2014, FY2015, and FY2017 did not occur until after the beginning of the new calendar year. |

In contrast to the annual appropriations measures tracked in the figure, supplemental appropriations move on a more ad hoc basis, when an unanticipated need for additional funding arises. Supplemental funding was provided more often prior to passage of the Budget Control Act in 2011,3 when the Federal Emergency Management Agency's (FEMA's) Disaster Relief Fund (DRF) would often rely on supplemental appropriations to replenish itself when a disaster struck and ensure resources would be available for initial recovery efforts. The Budget Control Act created a special limited exemption from the limits on discretionary spending for funding the federal costs of response to major disasters. This limited exemption has allowed the Disaster Relief Fund to carry a more robust balance, and thus be prepared to respond in the weeks and months after a major disaster without needing immediate replenishment by a supplemental appropriations bill. This has allowed the timing of supplemental appropriations driven by disaster relief funding for DHS to slow down.

This slowdown in timing can be seen by comparing the Hurricane Katrina supplemental appropriations in 2005 to the Hurricane Sandy supplemental appropriations in 2012-2013. The former had a request for supplemental appropriations three days from the date of disaster declaration and took four days from the date of disaster declaration to be enacted. In contrast, the latter took 38 days for a supplemental appropriations request to be submitted to Congress, and took three months from the date of declaration for supplemental appropriations to be enacted.4 At the time Hurricane Sandy made landfall, FEMA had over $7 billion available,5 almost three times more than was on hand when Hurricane Katrina came ashore.6

DHS Appropriations Trends: Size

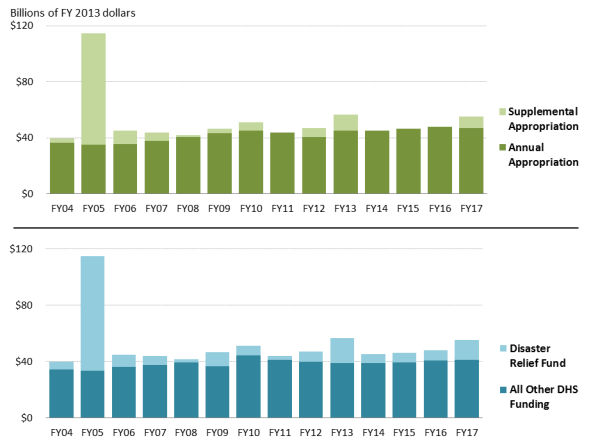

The tables and figure below present information on DHS discretionary appropriations, as enacted, for FY2004 through FY2017. Table 1 provides data in nominal dollars, while Table 2 provides data in constant FY2013 dollars to allow for comparisons over time. Figure 2 represents Table 2's data in a visual format.

The totals include annual appropriations as well as supplemental appropriations.

Making meaningful comparisons over time for the department's appropriations as a whole is complicated by a variety of factors, the two most significant of which are the frequency of supplemental appropriations for the department, and the impact of disaster assistance funding.

Often supplemental appropriations are enacted in response to a critical need: one of the most common of those is a major disaster where the federal government is called on for assistance. FEMA's Disaster Relief Fund (DRF) is where the majority of that emergency response is funded.7

Supplemental funding, which frequently addresses congressional priorities, such as disaster assistance and border security, varies widely from year to year and as a result distorts year-to-year comparisons of total appropriations for DHS. In the department's initial fiscal year of operations, it received over $5 billion in supplemental funding during that fiscal year in addition to all the resources transferred with the department's components. Twenty-one separate supplemental appropriations acts have provided appropriations to the department since it was established. Gross supplemental appropriations provided to the department in those acts exceed $120 billion.

Table 1 and Table 2, in their second and third columns, provide amounts of new discretionary budget authority provided to DHS from FY2004 through FY2017, and a total for each fiscal year in the fourth column.

Disaster assistance funding is a key part of DHS appropriations. FEMA is one of DHS's larger component budgets, and funding for the DRF, which funds a large portion of the costs incurred by the federal government in the wake of disasters, is a significant driver of that budget. Of the billions of dollars provided to the DRF each year, only a single-digit percentage of this funding goes to pay for FEMA personnel and administrative costs tied to disasters; the remainder is provided as assistance to states, communities, and individuals. The gross level of funding provided to the DRF has varied widely since the establishment of DHS depending on the occurrence and size of disasters, from less than $3 billion in FY2008 to more than $60 billion in FY2005 in response to a series of hurricanes, including Hurricane Katrina. Table 1 and Table 2, in their fifth columns, provide the amount of new budget authority provided to the DRF, and in the sixth column, show the total new budget authority provided to DHS without counting the DRF.

Figure 2 presents two perspectives on the overall total in constant FY2013 dollars:

- the top graph shows the split between annual and supplemental appropriations for DHS,

- the second chart breaks out the DRF from the rest of the DHS discretionary appropriations.

In nominal dollars, FY2017 annual appropriations (excluding the DRF and supplemental appropriations) represented the highest funding level for the department, surpassing the mark set in FY2016.

In constant dollars, the highest level of appropriations for the DHS budget without counting the DRF was FY2010. Annual appropriations funding declined from then through FY2013. Excluding the DRF, postsequestration funding levels for the department were approximately $38.9 billion in FY2013, which was the lowest funding level for the department in constant dollars since FY2009. In constant dollars (also excluding the DRF), FY2017 funding for the department enacted in P.L. 115-31 was the second-highest level in its history, and the most provided in a single appropriations act.

Table 1. DHS New Discretionary Budget Authority, FY2004-FY2017

(billions of dollars of budget authority)

|

Fiscal Year |

Annual Appropriations |

Supplemental Appropriations |

Total |

Disaster Relief Fund (DRF) Funding |

Total Less DRF Funding |

|||||

|

FY2004 |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

FY2005 |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

FY2006 |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

FY2007 |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

FY2008 |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

FY2009 |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

FY2010 |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

FY2011 |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

FY2012 |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

FY2013 |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

FY2013 postsequester |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

FY2014 |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

FY2015 |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

FY2016 |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

FY2017 |

|

|

|

|

|

Source: CRS analysis of congressional appropriations documents: for FY2004, H.Rept. 108-280 (accompanying P.L. 108-90), H.Rept. 108-76 (accompanying P.L. 108-11), P.L. 108-69, P.L. 108-106, and P.L. 108-303; for FY2005, H.Rept. 108-774 (accompanying P.L. 108-334), P.L. 108-324, P.L. 109-13, P.L. 109-61, and P.L. 109-62; for FY2006, H.Rept. 109-241 (accompanying P.L. 109-90), P.L. 109-148, and P.L. 109-234; for FY2007, H.Rept. 109-699 (accompanying P.L. 109-295) and P.L. 110-28; for FY2008, Division E of the House Appropriations Committee Print (accompanying P.L. 110-161) and P.L. 110-252; for FY2009, Division D of House Appropriations Committee Print (accompanying P.L. 110-329), P.L. 111-5, P.L. 111-8, and P.L. 111-32; for FY2010, H.Rept. 111-298 (accompanying P.L. 111-83), P.L. 111-212, and P.L. 111-230; for FY2011, P.L. 112-10 and H.Rept. 112-331 (accompanying P.L. 112-74); for FY2012, H.Rept. 112-331 (accompanying P.L. 112-74) and P.L. 112-77; for FY2013, Senate explanatory statement (accompanying P.L. 113-6), P.L. 113-2, the DHS Fiscal Year 2013 Post-Sequestration Operating Plan dated April 26, 2013, and financial data from the Hurricane Sandy Rebuilding Task Force Home Page at http://portal.hud.gov/hudportal/HUD?src=/sandyrebuilding/recoveryprogress; for FY2014, the explanatory statement accompanying P.L. 113-76; for FY2015, P.L. 114-4 and its explanatory statement as printed in the Congressional Record of January 13, 2015, pp. H275-H322; for FY2016, Div. F of P.L. 114-113 and its explanatory statement as printed in the Congressional Record of December 17, 2015, pp. H10161-H10210; for FY2017, Div. F of P.L. 115-31, its explanatory statement as printed in the Congressional Record of May 3, 2017, pp. H3807-H3873, and P.L. 115-56.

Notes: Emergency funding, appropriations for overseas contingency operations, and funding for disaster relief under the Budget Control Act's allowable adjustment are included. Transfers from the Department of Defense and advance appropriations are not included. Emergency funding in regular appropriations bills is treated as regular appropriations. Numbers in italics do not reflect the impact of sequestration.

Table 2. DHS New Discretionary Budget Authority, FY2013 Dollars, FY2004-FY2016

(billions of dollars of budget authority, adjusted for inflation)

|

Fiscal Year |

Regular |

Supplemental |

Total |

Disaster Relief Fund (DRF) Funding |

Total Less DRF Funding |

|

FY2004 |

36,472 |

3,087 |

39,559 |

5,261 |

34,298 |

|

FY2005 |

34,956 |

79,630 |

114,587 |

81,064 |

33,523 |

|

FY2006 |

35,432 |

9,393 |

44,825 |

8,882 |

35,943 |

|

FY2007 |

37,920 |

5,748 |

43,668 |

6,248 |

37,420 |

|

FY2008 |

40,688 |

965 |

41,654 |

2,472 |

39,182 |

|

FY2009 |

43,035 |

3,482 |

46,517 |

10,053 |

36,465 |

|

FY2010 |

45,275 |

5,890 |

51,165 |

7,085 |

44,080 |

|

FY2011 |

43,887 |

— |

43,887 |

2,738 |

41,149 |

|

FY2012 |

40,580 |

6,483 |

47,063 |

7,192 |

39,871 |

|

FY2013 |

46,555 |

12,072 |

58,627 |

18,495 |

40,132 |

|

FY2013 postsequester |

44,971 |

11,468 |

56,439 |

17,566 |

38,873 |

|

FY2014 |

45,119 |

— |

45,119 |

6,126 |

38,993 |

|

FY2015 |

46,200 |

— |

46,200 |

6,882 |

39,318 |

|

FY2016 |

47,881 |

— |

47,881 |

7,157 |

40,723 |

|

FY2017 |

47,080 |

8,102 |

55,182 |

13,973 |

41,209 |

Source: CRS analysis of congressional appropriations documents: for FY2004, H.Rept. 108-280 (accompanying P.L. 108-90), H.Rept. 108-76 (accompanying P.L. 108-11), P.L. 108-69, P.L. 108-106, and P.L. 108-303; for FY2005, H.Rept. 108-774 (accompanying P.L. 108-334), P.L. 108-324, P.L. 109-13, P.L. 109-61, and P.L. 109-62; for FY2006, H.Rept. 109-241 (accompanying P.L. 109-90), P.L. 109-148, and P.L. 109-234; for FY2007, H.Rept. 109-699 (accompanying P.L. 109-295) and P.L. 110-28; for FY2008, Division E of the House Appropriations Committee Print (accompanying P.L. 110-161) and P.L. 110-252; for FY2009, Division D of House Appropriations Committee Print (accompanying P.L. 110-329), P.L. 111-5, P.L. 111-8, and P.L. 111-32; for FY2010, H.Rept. 111-298 (accompanying P.L. 111-83), P.L. 111-212, and P.L. 111-230; for FY2011, P.L. 112-10 and H.Rept. 112-331 (accompanying P.L. 112-74); for FY2012, H.Rept. 112-331 (accompanying P.L. 112-74) and P.L. 112-77; for FY2013, Senate explanatory statement (accompanying P.L. 113-6), P.L. 113-2, the DHS Fiscal Year 2013 Post-Sequestration Operating Plan dated April 26, 2013, and financial data from the Hurricane Sandy Rebuilding Task Force Home Page at http://portal.hud.gov/hudportal/HUD?src=/sandyrebuilding/recoveryprogress; for FY2014, the explanatory statement accompanying P.L. 113-76; for FY2015, P.L. 114-4 and its explanatory statement as printed in the Congressional Record of January 13, 2015, pp. H275-H322; Div. F of P.L. 114-113 and its explanatory statement as printed in the Congressional Record of December 17, 2015, pp. H10161-H10210, Div. F of P.L. 115-31 and its explanatory statement as printed in the Congressional Record of May 3, 2017, pp. H3807-H3873, and P.L. 115-56. Deflator based on data in Table 1.3, Historical Tables, Budget of the U.S. Government, Fiscal Year 2018, as retrieved from https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/Historicals on June 9, 2017.

Notes: Emergency funding, appropriations for overseas contingency operations, and funding for disaster relief under the Budget Control Act's allowable adjustment are included. Transfers from the Department of Defense and advance appropriations are not included. Emergency funding in regular appropriations bills is treated as regular appropriations. Numbers in italics do not reflect the impact of sequestration.

|

Figure 2. DHS Appropriations, FY2004-FY2017, Showing Supplemental Appropriations and the DRF (in billions of constant FY2013 dollars) |

|

|

Source: CRS analysis of congressional appropriations documents: for FY2004, H.Rept. 108-280 (accompanying P.L. 108-90), H.Rept. 108-76 (accompanying P.L. 108-11), P.L. 108-69, P.L. 108-106, and P.L. 108-303; for FY2005, H.Rept. 108-774 (accompanying P.L. 108-334), P.L. 108-324, P.L. 109-13, P.L. 109-61, and P.L. 109-62; for FY2006, H.Rept. 109-241 (accompanying P.L. 109-90), P.L. 109-148, and P.L. 109-234; for FY2007, H.Rept. 109-699 (accompanying P.L. 109-295) and P.L. 110-28; for FY2008, Division E of the House Appropriations Committee Print (accompanying P.L. 110-161) and P.L. 110-252; for FY2009, Division D of House Appropriations Committee Print (accompanying P.L. 110-329), P.L. 111-5, P.L. 111-8, and P.L. 111-32; for FY2010, H.Rept. 111-298 (accompanying P.L. 111-83), P.L. 111-212, and P.L. 111-230; for FY2011, P.L. 112-10 and H.Rept. 112-331 (accompanying P.L. 112-74); for FY2012, H.Rept. 112-331 (accompanying P.L. 112-74) and P.L. 112-77; for FY2013, Senate explanatory statement (accompanying P.L. 113-6), P.L. 113-2, the DHS Fiscal Year 2013 Post-Sequestration Operating Plan dated April 26, 2013, and financial data from the Hurricane Sandy Rebuilding Task Force Home Page at http://portal.hud.gov/hudportal/HUD?src=/sandyrebuilding/recoveryprogress; for FY2014, the explanatory statement accompanying P.L. 113-76; for FY2015, P.L. 114-4 and its explanatory statement as printed in the Congressional Record of January 13, 2015, pp. H275-H322; Div. F of P.L. 114-113 and its explanatory statement as printed in the Congressional Record of December 17, 2015, pp. H10161-H10210, Div. F of P.L. 115-31 and its explanatory statement as printed in the Congressional Record of May 3, 2017, pp. H3807-H3873, and P.L. 115-54. Notes: Emergency funding, appropriations for overseas contingency operations, and funding for disaster relief under the Budget Control Act's allowable adjustment are included. Transfers from the Department of Defense and advance appropriations are not included. Emergency funding in regular appropriations bills is treated as regular appropriations. FY2013 reflects the impact of sequestration. |