Overview

Nearly six years after a U.S.-led NATO military intervention helped Libyan rebels topple the authoritarian government of Muammar al Qadhafi, Libya remains politically fragmented. Its security is threatened by terrorist organizations and infighting among interim leaders and locally organized armed groups. Rival governing entities based in eastern and western Libya have engaged in a heated political dispute since agreeing in December 2015 to establish a Government of National Accord (GNA).

GNA Prime Minister-designate Fayez al Sarraj and officials affiliated with a nine-member GNA Presidency Council entered Tripoli in early 2016 but have not consolidated control over government institutions nationally or unified competing groups. The leaders of the eastern Libya-based House of Representatives (HOR, elected in 2014) have withheld endorsement of the GNA Presidency Council's proposed cabinet with the backing of General Khalifa Haftar's eastern Libya-based Libyan National Army (LNA) movement. Haftar and his allies have asserted control over key oil infrastructure sites in east-central Libya, giving them considerable influence over the country's fiscal future.

Various international efforts to mediate among Libyans have struggled to gain traction, and outside parties have pursued their own individual interests in the country. The U.N. Security Council has recognized the GNA as Libya's governing authority since 2015, even as General Haftar and his supporters have increased their political-military influence. The LNA has grown in strength with the support of outside actors, in spite of a U.N. arms embargo. The United States and the European Union have placed sanctions on some Libyan leaders for obstructing the implementation of the 2015 agreement, amid an evolving pattern of competition and dialogue between the GNA Presidency Council and eastern Libya-based figures.

In September 2017, the U.N. Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL) launched a new Action Plan to amend the 2015 Libyan Political Agreement and reenergize the stalled transition. The U.N. plan is intended to replace what UNSMIL Head and Special Representative of U.N. Secretary-General Ghassan Salamé has described as a "proliferation" of such initiatives that have been pursued by Libya's neighbors and other foreign powers. U.S. officials stated in September that the United States "will not support individuals who seek to circumvent the U.N.-led political process."

The U.N. Action Plan's first step involves amending the 2015 political agreement to address issues that have prevented its implementation to date, such as differences over the size and role of a representative Presidency Council, the locus of executive authority, and the power to approve the leadership of national security bodies and civil service institutions. Next steps are to include the drafting and adoption of laws governing the holding of a constitutional referendum and national elections, followed by their implementation some time in 2018.

Some Members of Congress and U.S. officials are considering options for future engagement in Libya with two interrelated goals: supporting the emergence of a unified, capable national government, and reducing transnational threats posed by Libya's instability and Libya-based terrorists. Pursuing these goals simultaneously presents U.S. policymakers with choices regarding priorities. Decisions include the types and timing of possible aid and/or interventions, the nature and extent of U.S. partnership with various Libyan groups, the utility of sanctions or other coercive measures, and relations with other countries pursuing their own interests in Libya.

The Trump Administration has requested additional foreign assistance to continue U.S. transition support programs and may propose new security assistance programs if reconciliation measures prove fruitful. If U.N.-sponsored transition completion efforts fail, then U.S. decision makers might reassess U.S. options for addressing security threats emanating from the country.

|

|

|

Land Area: 1.76 million sq. km. (slightly larger than Alaska); Boundaries: 4,348 km (~40% more than U.S.-Mexico border); Coastline: 1,770 km (more than 30% longer than California coast) Population: 6,653,210 (July 2017 est., 2015 U.N. estimated 12% were immigrants), 42.9% <25 years old GDP PPP: $55.4 billion; annual real % change: -4.4% (2016 est.); per capita: $8,700 (2016 est.) Budget (spending; balance): $13.71 billion, deficit 20.1% of GDP (2016 est.) External Debt: $3.53 billion (December 2016 est.) Foreign Exchange Reserves: $56.15 billion (December 2016 est.), $73.83 billion (December 2015 est.), $124 billion (2012 est.) Oil and natural gas reserves: 48.36 billion barrels (2016 est.); 1.505 trillion cubic meters (2016 est.) |

Source: Congressional Research Service using data from U.S. State Department, Esri, United Nations, and Google Maps. Country data from CIA World Factbook, September 2017.

|

Developments in 2017 On September 14, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson met in London with representatives of the United Arab Emirates, Italy, the United Kingdom, Egypt, and France "to find a way forward in Libya that creates stability and reconciliation, and that restores Libya under a functioning government."1 On September 20, the United Nations Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL) convened a high level meeting at the United Nations General Assembly in New York and laid out its Action Plan for moving the transition forward and coordinating international aid. The United States, the African Union (AU), the European Union (EU), and the League of Arab States (LAS) have all endorsed the U.N. Action Plan. In late September, UNSMIL-facilitated Joint Drafting Committee talks began in Tunis between figures affiliated with the GNA's State Council and the eastern Libya-based House of Representatives. The talks aim at generating agreement over proposed amendments to the 2015 Libyan Political Agreement. The parties reached agreement on a proposed reduction in the size of the GNA Presidency Council from nine to three and the creation of a separate executive authority under a new prime minister. The delegates then turned to discussing changes to chain of military command arrangements, the makeup of the GNA State Council, and constitutional issues. In talks in Abu Dhabi in May 2017, Libyan National Army leader Khalifa Haftar proposed a reduction in the size of the GNA presidency council to include GNA Prime Minister-designate Fayez al Sarraj, himself, and House of Representatives (HOR) leader Aquila Issa Saleh. Haftar reportedly also proposed changes that would see military authority consolidated under his control. Subsequent discussions have refined these proposals and others in search of consensus. U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM) announced that U.S. forces conducted airstrikes against Islamic State positions south of Sirte on September 22 and September 26, killing IS fighters and the destroying arms and vehicles. U.S. military statements said the Islamic State used the targeted locations as transit hubs and operational planning centers, including for external attacks. IS fighters appear to have regrouped in rural areas after fleeing the central coastal city of Sirte in late 2016, and the group has claimed a series of attacks on Libyan forces in 2017. Clashes erupted in the western Libya town of Sabratha between local militia groups, including a force that reportedly has partnered with Italian authorities to restrict human trafficking operations. The unrest underscores the continuing influence of local armed groups and the tendency for rivalry among them to disrupt security. Clashes in Tripoli days after the May 2017 visit of senior U.S. officials resulted in dozens of fighters being killed, with GNA-aligned forces later asserting more control over the capital and expelling rivals. The International Organization for Migration (IOM) cites accounts from migrants transiting southwest Libya that "slave markets" are operating intermittently in the south of the country, echoing details in accounts reported in an April New Yorker magazine story on the passage of African migrants through Libya to Europe.2 While the IOM reported that arrivals by sea to Italy had increased 25% in the first five months of 2017 compared to the same period in 2016, arrivals declined precipitously over the summer months, following the implementation of an agreement between the Italian government and some west Libya-based armed groups to target traffickers. More than 2,470 deaths at sea have occurred off Libya's coast over this period, amid intensified rescue-at-sea efforts. A significant drop in the Libyan dinar's value against the dollar in Libyan exchange markets is generating popular concern and fears of unrest. The official rate of exchange was reportedly roughly one-sixth of the black market rate as of mid-June 2017. Rising inflation, the widespread use of informal and black market currency exchange, and rampant criminality are placing significant economic pressure on citizens already struggling to cope with unrest. LNA forces announced victory in their operations against opponents in Benghazi and imposed a siege on the eastern Libyan city of Darnah, which remains under the control of Islamist militia forces. Darnah-based Islamists repulsed an Islamic State attempt to assert control over the city in 2015.3 On June 1, the U.N. Resolution 1970 Committee on Libya's Panel of Experts issued its final report for the year, documenting violations of the arms embargo on the country and warning of "escalating armed conflict." On June 12, the Security Council unanimously extended maritime arms embargo enforcement provisions for one year in Resolution 2357. On June 22, U.N. Secretary General António Guterres appointed Ghassan Salamé as his Special Representative and UNSMIL head, replacing Martin Kobler. The Security Council adopted Resolution 2362—extending the mandate for maritime enforcement of oil shipment monitoring and reaffirming arms embargo, asset freeze, and travel ban measures—and Resolution 2376-- extending UNSMIL's mandate to September 2018. |

Political, Diplomatic, and Security Dynamics

Libya's 2011 uprising and conflict brought Muammar al Qadhafi's four decades of authoritarian rule to an end. Competing factions and alliances—organized along local, regional, ideological, tribal, and personal lines—have jockeyed for influence and power in post-Qadhafi Libya, at times with the backing of rival foreign governments. Although some observers attribute this competition to simple binaries—"Islamist versus secular," "east versus west," "tribe versus tribe," "urban versus rural," "ethnic majority versus ethnic minority,"4 or "old-regime officials versus newly empowered groups"—many of these factors and others often interact to shape local and national dynamics. After years of rivalry and conflict, many Libyan actors make claims to some degree of political legitimacy and possess some means to assert themselves by force, but none have consolidated enough political support or military force to provide credible leadership or durable security on a national scale.

In this context, key post-Qadhafi political issues for Libyans have included

- the relative powers and responsibilities of local, regional, and national government;

- the weakness of national government institutions and security forces;

- the role of Islam in political and social life;

- the involvement in politics and security of former regime officials; and

- the proper management of the country's large energy reserves, related infrastructure, and associated revenues.

Factors that have shaped the relative degree of conflict, mutual accommodation, and reconciliation among Libyan factions since 2014 include

- the relative ability of numerous factions to muster sufficient force or legitimacy to assert dominance over each other;

- the inability of rival claimants to gain exclusive access to government funds controlled by the Central Bank or sovereign assets held overseas;

- the U.N. arms embargo and the potential widening of the reach of U.N. sanctions; and

- the threats posed to Libyans by extremist groups, including the Islamic State.

Among the range of external actors seeking to shape developments in Libya, the United States has at times acted unilaterally and directly to protect its national security interests. Other countries have done the same. At the same time, the United States and other external parties have expressed support for multilateral initiatives to encourage compromise and consensus in support of Libya's transition. For the United States and other outside powers, key issues related to post-Qadhafi Libya have included

- transnational terrorist and criminal threats emanating from Libya;

- the security and continued export of Libyan oil and natural gas;

- Libya's role as a transit country for Europe-bound refugees and migrants;

- the security of Libyan weapons stockpiles and unconventional weapons materials; and

- the country's orientation in various region-wide political competitions.

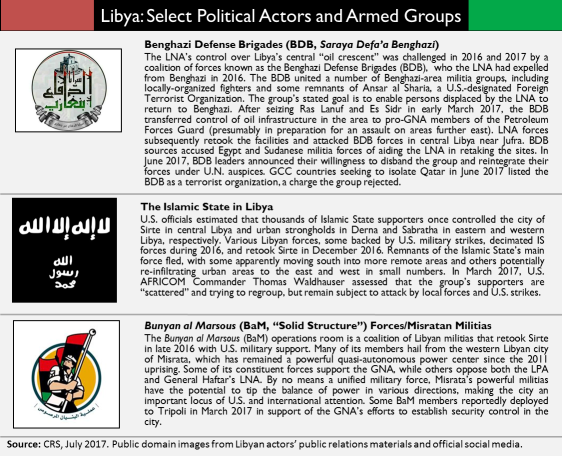

For a more detailed description of Libya's history and political evolution, see Appendix A. For a description of select Libyan political actors, see Appendix D.

Libya's Political Landscape

Developments in post-Qadhafi Libya have unfolded in three general phases, the third of which is still unfolding:

- 1. an immediate post-Qadhafi period (October 2011 to July 2012) focused on identifying interim leaders and recovery from the 2011 conflict;

- 2. a contested transitional period (July 2012 to May 2014) focused on legitimizing and testing the viability of interim institutions; and

- 3. a period of confrontation (May 2014 to present) characterized by tension and violence among loose political-military coalitions, and multifaceted conflict between their members and violent Islamist extremist groups.

In the initial consolidation phase, members of the anti-Qadhafi Transitional National Council (TNC) oversaw the promulgation of an interim constitutional declaration in August 2011 and the organization in July 2012 of the country's first general election since the 1950s. Early on, disagreements over the makeup and leadership of an interim cabinet hinted at the deeper political, ideological, interpersonal, and regional fault lines that would later disrupt the transition. The TNC government made little progress in reconstituting or reforming government entities, establishing security, or demobilizing militias that had formed to fight Qadhafi and his allies.

Although many Libyans expressed hope that the July 2012 national election for the General National Congress (GNC) would endow a new government with sufficient legitimacy and support to address sensitive issues, the contest heightened the stakes of political competition. The September 2012 attacks on U.S. personnel and facilities in Benghazi had a chilling effect on international efforts to support Libya's transition, as did subsequent incidents in which militia groups demonstrated their willingness and ability to disrupt the workings of the national government in order to preserve their interests. Overall, the GNC government's tenure was marred by gridlock, mutual suspicion, and political intimidation by armed groups.

By late 2013, amid preparations for another national election for members of a constitutional drafting assembly, GNC members were polarized by disputes over the GNC's remaining term of office, the passage of laws marginalizing former regime officials, and proposals to elevate the status of Islamic law in the country's legal system. Disputes flared over governance, the selection of new interim representatives, and responsibility for ensuring security in the face of a rising wave of criminality and Islamist insurgent violence.

By mid-2014, the transition process outlined in 2011 had all but collapsed, and the outbreak of violence between two rival political-military coalitions compounded the complexity of Libya's already diverse, atomized security environment. The outcome of the June 2014 election for a new House of Representatives (HOR) to replace the GNC was contested by GNC holdouts, setting the stage for more than a year of stalemate and failed attempts at mediation (see textbox below). In eastern Libya, the Tobruk-based HOR and Benghazi-focused forces aligned with the Libyan National Army's (LNA's) "Operation Dignity" initiative asserted their legitimacy and moved to target a range of Islamist forces and other militias. In western Libya, the Tripoli-based remnants of the GNC and the GNC-aligned "Libya Dawn" militia grouping contested the HOR's legitimacy and rejected the LNA. Over time, individual members of these two coalitions reached parallel cease-fire agreements, and some communities and militias agreed to participate in U.N.-sponsored peace talks. Divisions and disputes persisted, repeated attempts to broker an agreement failed, and political relationships remained fluid through 2015.

The Skhirat Agreement and the Government of National Accord

In December 2015, a U.N.-facilitated Libyan Political Agreement (LPA) was signed in Skhirat, Morocco, bringing together members of Libya's competing coalitions to call for the creation of a new, inclusive Government of National Accord (GNA). The GNA was designed to incorporate members of opposing groups and rival post-Qadhafi elected bodies under new institutional arrangements. The agreement calls for the nine-member GNA Presidency Council made up of representatives from Libya's key factions and regions to assume national security and economic decisionmaking power, with the HOR retaining legislative power in partnership with a new State Council made up in part of former GNC members.5

Libyan politics have since been defined in large part by Libyans' evolving views of the agreement and the repositioning of locally organized political councils and militias in response to GNA leaders' attempts to implement it. The HOR accepted the GNA agreement in principle in late January 2016, but HOR leaders have prevented the wider body from endorsing the GNA's proposed cabinet through a required procedural vote and constitutional amendment process. HOR members aligned with General Khalifa Haftar in eastern Libya (see textbox above) have opposed the terms of an annex of the agreement that calls for command of the military to shift to the GNA's Presidency Council once the agreement is ratified. HOR leader Aqilah Issa Saleh appointed General Haftar as military commander in March 2015 after the HOR voted to create the position.

Pro-Haftar forces have largely consolidated security control over much of northeastern Libya, and in September 2016 moved to take control of important oil infrastructure sites in the Sirte basin. Although they subsequently transferred key facilities to friendly Petroleum Forces Guard members and allowed national oil authorities to operate them, the move appeared to increase Haftar's insistence upon being recognized as the legitimate leader of Libya's armed forces and his allies' insistence on rejecting the GNA Presidency Council. LNA figures continue to warn against the incorporation of what they consider to be militias or extremists into national security bodies, a position widely viewed as seeking the exclusion of some of their pro-GNA counterparts.

In western Libya, some former GNC members and some militia forces formerly aligned with the "Libya Dawn" grouping have announced their support for the GNA and have stepped forward to defend the GNA Presidency Council's limited presence in Tripoli. Some western Libya-based GNA supporters have called for the exclusion of General Haftar from a security role in any future government. Some pro-GNA militia forces in western Libya, including forces that have battled with U.S. military support to recapture the city of Sirte from the Islamic State organization, may now seek an enhanced security role for themselves, setting up the prospect of renewed confrontation.

GNA Prime Minister-designate Fayez al Sarraj and Khalifa Haftar met in Abu Dhabi in May 2017 and in Paris in July, raising hopes that a process leading to an agreed amendment of the LPA is possible. U.N.-sponsored talks in September produced agreement on steps to reduce the size of the GNA Presidency Council and create a separate prime ministership, but prospects for agreement over security arrangements are uncertain. Reports suggest that Haftar has proposed changes to the GNA's structure that would grant him formal national security authorities, and both Prime Minister-designate Sarraj and Haftar have issued decrees delineating military zone systems for the country and appointing regional military commanders in 2017. The Constitutional Drafting Assembly approved an amended draft constitution in July 2017. Further revisions and consideration of referendum legislation are expected before the constitution can be enacted.6

If the GNA framework and underlying political agreement are amended, Libyan authorities may be better able to form a more united front against disruptive local armed groups and Islamist insurgents, especially surviving members of the Islamic State's Libyan branch. The Islamic State, while weakened, has threatened all parties in the country that reject its vision and plans. Key policy areas are likely to remain politically sensitive and potentially divisive, including those concerning the composition and leadership of Libyan security forces, efforts to combat extremist groups, the nature and extent of Libyan requests for international security assistance, demobilization of local militias, and the security of energy infrastructure sites vital to the country's economic future.

Sanctions and Arms Embargo Provisions

Prior to and following the outbreak of conflict in Libya in 2011, the United Nations, the United States, and other actors adopted a range of sanctions measures intended to convince the Qadhafi government to end its military campaign against opposition forces and civilians. The measures also sought to dissuade third parties from providing arms or facilitating financial transactions for the benefit of Libyan combatants. United Nations Security Council Resolution 1970 established a travel ban on Qadhafi government leaders, placed an embargo on the unauthorized provision of arms to Libya, and froze certain Libyan state assets. In February 2011, President Barack Obama issued Executive Order 13566, blocking the property under U.S. jurisdiction of the government of Libya, Qadhafi, his family, and other designated individuals.

After the conclusion of the 2011 conflict, U.N. and U.S. sanctions measures were modified but remained focused on preventing former Qadhafi government figures from accessing Libyan state funds and undermining Libya's transition. Asset-freeze measures changed to give transitional leaders access to some state resources, but some limitations also remained in place to ensure that funds were transparently and legitimately administered by transitional authorities. U.S. Treasury officials issued a series of general licenses that gradually unblocked most Libyan state property and allowed for transactions with Libyan Central Bank and Libyan National Oil Company. U.N. arms embargo provisions were modified over time, but remained in place in a bid to ensure that weapons transfers to Libya were authorized by the transitional government.

When fighting broke out among Libyan factions in 2014, the Security Council moved to expand the scope of the modified sanctions provisions to allow for the targeting of actors who were contributing to the conflict. Resolution 2174, adopted in August 2014, authorized the placement of U.N. financial and travel sanctions on individuals and entities in Libya and internationally found to be "engaging in or providing support for other acts that threaten the peace, stability or security of Libya, or obstruct or undermine the successful completion of its political transition." Resolution 2213, adopted in March 2015, expanded the scope of sanctionable activities related to the standard articulated in Resolution 2174. At present, modified sanctions provisions of Resolutions 1970, 2174, and 2213 remain in force.

The U.N. Security Council endorsed the Skhirat Agreement in December 2015 by adopting Resolution 2259, which calls on member states to support the implementation of the agreement, reiterates the threat of possible sanctions against spoilers, and calls for member states to provide security support to the GNA upon request. Security Council Resolution 2278, adopted on March 31, 2016, identifies the GNA as the party of responsibility for engagement with the Security Council on issues related to Libyan financial institutions, oil exports, and arms transfers.

Resolutions 2259, 2278, and 2362 call on Member States to recognize and support the Government of National Accord and to comply with Security Council efforts to enforce asset freeze, travel ban, and arms embargo measures. HOR and LNA leaders have continued to advocate for the lifting of arms embargo restrictions on their forces. During 2017, they have questioned the GNA's authority over security, financial, and energy matters, and described themselves as the rightful leaders of the country's security forces.7

Resolution 2278 "urges Member States to assist the Government of National Accord, upon its request, by providing it with the necessary security and capacity building assistance, in response to threats to Libyan security and in defeating ISIL, groups that have pledged allegiance to ISIL, Ansar Al Sharia, and other groups associated with Al-Qaida operating in Libya." U.S. military operations in Libya against the Islamic State since 2016 have been undertaken at the request of GNA Prime Minister-designate Al Sarraj.

U.S. and European Sanctions

The U.S. government modified its sanctions enforcement measures in support of the Skhirat agreement in April 2016, by amending the scope of the national emergency with respect to Libya declared in Executive Order 13566. The amendments were based on President Barack Obama's finding that

the ongoing violence in Libya, including attacks by armed groups against Libyan state facilities, foreign missions in Libya, and critical infrastructure, as well as human rights abuses, violations of the arms embargo imposed by United Nations Security Council Resolution 1970 (2011), and misappropriation of Libya's natural resources threaten the peace, security, stability, sovereignty, democratic transition, and territorial integrity of Libya and thereby constitute an unusual and extraordinary threat to the national security and foreign policy of the United States.

President Obama extended the national emergency with respect to Libya for one year before leaving office in January 2017.8

Under the modified executive order, property under U.S. jurisdiction may be blocked and entry to the United States may be prohibited for individuals and entities found to be engaging or to have engaged in a range of actions, including threatening the peace, stability, or security of Libya and obstructing, undermining, delaying, or impeding the adoption of or transfer of power to a Government of National Accord or successor government. To date, the U.S. government has placed sanctions on former GNC government prime minister Khalifa Ghwell and HOR leader Aqilah Issa Saleh for obstructing the implementation of the Skhirat Agreement.

The European Union consolidated its sanctions on Libya in January 2016.9 In April 2016, the European Union imposed sanctions on Saleh, Ghwell, and GNC official Nuri Abu Sahmain. The EU extended its sanctions in March 2017.10

Arms Embargo Enforcement and Violations

Under current U.N. Security Council resolutions, arms transfers to Libya may occur provided the GNA approves and the transfer is notified to the United Nations panel established pursuant to Security Council Resolution 1970. In practice, unauthorized arms transfers to Libya continue to take place, as documented in reports produced by the Resolution 1970 committee and its Panel of Experts.11 The Panel of Experts report released in June 2017 documents lethal and nonlethal foreign support in violation of the arms embargo for armed groups from eastern Libya and Misrata, including support for the expansion of both sides' air force capabilities.12

In June 2016, the Security Council adopted Resolution 2292 authorizing member states to assist in the maritime enforcement of the arms embargo, extended in June 2017 by Resolution 2357. The EU has authorized its migration-focused naval mission in the Mediterranean to assist in arms embargo enforcement.

Struggles for control over Libya's central "oil crescent" and adjacent areas in 2017 have led some observers to warn of a potential expansion of unauthorized foreign military assistance to parties to the conflict.13 In March 2017, the commander of U.S. AFRICOM, General Thomas Waldhauser, expressed particular concern about possible Russian intervention in Libya on behalf of General Haftar and the LNA.14

Oil, Fiscal Challenges, and Institutional Rivalry

Conflict and instability in Libya have taken a severe toll on the country's economy and weakened its fiscal and reserve positions since 2011. Oil and natural gas sales supply 97 percent of the government's fiscal revenue, and a combination of supply disruptions and market forces devastated national finances from 2014 through 2016. The estimated budget deficit was 49 percent of GDP in 2015 and was even greater in 2016, as "budget revenues and exports proceeds reached the lowest amounts on record because of low oil production and prices."15 As of August 2016, conflict and budget shortfalls had caused oil production to plummet to below 300,000 barrels per day (bpd) out of an overall capacity of 1.6 million bpd.16 World Bank/International Monetary Fund statistics and U.N. estimates suggest that foreign exchange reserves have fallen precipitously from their high point of $124 billion in 2012, and may be as little as $45 billion at the end of 2017.17

An expansion of oil production in 2017 has provided a much-needed injection of new financial resources, with production having since rebounded to more than 900,000 bpd.18 Nevertheless, fighting near the oil crescent region and intermittent shutdowns of pipelines by militias have raised the prospect of potential disruptions or declines. As Libyan production has rebounded, Libya has faced calls from some fellow OPEC members to participate in the group's shared production cut agreement. Libyan authorities have not made any commitments with regard to the OPEC agreement and reportedly still hope to increase domestic production to 1.25 million bpd by December 2017.19

Although revenue has declined since 2011, state financial obligations have increased, with public spending on salaries, imports, and subsidies all having expanded. Salaries and subsidies reportedly consumed 93% of the state budget as of September 2016.20 Government payments to civilians and militia members have continued since the outbreak of conflict in 2014, and Central Bank authorities have simultaneously paid salaries for military and militia forces aligned with opposing sides in the internal conflicts. In December 2016, then-SRSG Kobler described strained ties between the Central Bank and the GNA Presidency Council, and warned that "the country will face an economic meltdown unless something changes."21

In August 2017, the U.N. Secretary-General reported that "the budget deficit is much higher than previously projected" and predicted that foreign currency reserves would remain dangerously low through the end of 2017.22 The United States has facilitated economic dialogue meetings among representatives of implementing and auditing agencies to improve budget execution, but serious challenges remain.

Among these challenges are unresolved rivalries among parallel leaders of key national institutions such as the Central Bank, National Oil Company (NOC), and Libya's sovereign wealth fund—the Libya Investment Authority (LIA). These rivalries have reflected the country's underlying political competition over time.

- Central Bank officials in Tripoli and Bayda have become embroiled in the rivalry between the GNA Presidency Council and the HOR government, with the United States and other backers of the GNA Presidency Council recognizing the Tripoli-based institution as legitimate.23 In May 2016, the Bayda-based bank moved to issue its own currency and to access secured assets held at the Bayda Central Bank branch, leading the U.S. government to warn against actions not authorized by the GNA Presidency Council that could undermine confidence among Libyan consumers and international trading partners.24

- In August 2016, the GNA Presidency Council named an interim steering committee for the LIA after a long-simmering dispute between rival board members and chairmen brought the fund's leadership to a standstill.25 The LIA's assets reportedly exceed $60 billion, much of which remain frozen pursuant to U.N. Security Council Resolutions 1970 and 1973 (2011), as modified by Resolution 2009 (2011). The GNA council authorized the steering committee to represent the LIA in ongoing legal proceedings, but not to manage assets. In February and May 2017, Libyan court rulings invalidated the GNA appointment and authorization on the grounds that the GNA's tenure had still not been approved under the terms of the LPA. Leadership of the LIA remains in dispute.26

- Disputes involving the National Oil Company also have ebbed and flowed since early 2016. In April 2016, the U.N. Security Council blacklisted an oil tanker that had taken on hundreds of thousands of barrels of oil sold by the HOR-affiliated branch of the national oil company, but the sanctions were withdrawn at the GNA Presidency Council's request on May 12.27 A deal to unite the Tripoli and Benghazi branches of the NOC was reached in early July 2016, but appeared to unravel later that month after GNA officials reached a related agreement with Petroleum Forces Guard personnel that then held key oil infrastructure.28 Benghazi-based NOC officials issued statements lifting force majeure orders on oil terminals seized by LNA forces in September 2016 and in March 2017 moved to cancel the July 2016 agreement. Tripoli-based NOC Chairman Mustafa Sanalla has called for the NOC to be depoliticized and wrote in June 2017 that he and his colleagues "intend to remain neutral until there is a single legitimate government we can submit to."29

Conflict in Libya's Oil Crescent

The prospect for increased oil production from Libya has been clouded by intermittent conflict over important energy infrastructure locations among extremists, locally organized militia forces, and rival national coalitions. As the victory of pro-GNA forces over IS forces in Sirte began appearing more imminent during summer 2016, attention shifted to the question of control over oil export terminals in the eastern Sirte basin (see map in Table 1 above). Petroleum Facilities Guard (PFG) forces under the leadership of Ibrahim Jadhran asserted control over key terminals in the area in 2013, seeking to leverage that control in pursuit of payment and recognition from the state.30 The U.S. Navy assisted in returning an unauthorized oil cargo from a PFG-controlled terminal in March 2014.31 Jadhran reached an agreement with GNA officials in July 2016 to allow GNA-approved exports from terminals under PFG control in exchange for unspecified concessions.32 HOR and LNA figures remained highly critical of Jadhran, and signaled their intention to evict the PFG from the terminal areas.33

In August and early September 2016, LNA forces moved westward from Benghazi in a bid to assert control over local municipalities and then launched an operation to take control of oil terminals at Zuwaytina, Es Sidr/Sidra, Ras Lanuf, and Marsa al Burayqah. While some PFG fighters reportedly responded favorably to calls from their pro-LNA tribal leaders to acquiesce to the LNA move, others reportedly resisted and sporadic fighting was reported. A bid by Jadhran's supporters to retake facilities at Sidra and Ras Lanuf reportedly failed, as observers and officials warned that combat could cause damage that may disrupt future operations.

The LNA's move and the Benghazi-based NOC's embrace of it drew a range of responses from Libyans and third parties, including the United States. UNSMIL underscored the Security Council's recognition of the GNA Presidency Council as "the sole executive authority in Libya" and called for "all parties to avoid any damage to the oil facilities." In a joint statement, the governments of the United States, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom called for "all military forces that have moved into the oil crescent to withdraw immediately, without preconditions" and, inter alia, stated the signatories' "intent to enforce UNSCR 2259, including measures concerning illicit oil exports."34

The LNA and HOR governments rejected the statement and joined some other Libyans in describing it as interfering in Libyan affairs. GNA Prime Minister-designate Al Sarraj issued a statement rejecting foreign military intervention, calling for dialogue, and seeking an end to provocative actions.35 In March 2017, the Benghazi Defense Brigades took temporary control of facilities at Es Sidr and Ras Lanuf, leading the LNA to launch operations to retake them, which were successful. The United States and others subsequently have encouraged Libyans to find a solution that will avoid further confrontation.

If Libyans prove unwilling or unable to reach a compromise, third parties, including the United States, may face challenging choices about how to respond. In Resolution 2362 of June 2017, the U.N. Security Council extended the mandate through November 15, 2018, for member states to assist in preventing oil and oil product exports that are not authorized by the GNA.36 Resolution 2362 stresses "the need for the Government of National Accord to exercise sole and effective oversight over the National Oil Corporation, the Central Bank of Libya, and the Libyan Investment Authority as a matter of urgency, without prejudice to future constitutional arrangements pursuant to the Libyan Political Agreement."

The Islamic State and Other Violent Islamist Extremist Groups

The Islamic State established a branch of its organization in Libya after Libyan fighters and foreigners arrived from Syria in 2014, generating significant concern among Libyans and the international community.37 IS supporters announced three affiliated wilayah (provinces) corresponding to Libya's three historic regions—Wilayat Tripolitania in the west, Wilayat Barqa in the east, and Wilayat Fezzan in the southwest—and took control of Muammar al Qadhafi's hometown—the central coastal city of Sirte—in mid-2015. By early 2016, senior U.S. officials estimated that the group's strength had grown to as many as 6,000 personnel across the country, among a larger community of Libyan Salafi-jihadist activists and militia members.38 On May 19, 2016, the U.S. State Department announced the designation of the Islamic State's branch in Libya as a Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO) under Section 219 of the Immigration and Nationality Act and as a Specially Designated Global Terrorist (SDGT) entity under Executive Order 13224.39

As in other countries, IS supporters in Libya have faced resistance from a wide array of local armed groups—including Islamists—that do not share their beliefs or recognize the authority of IS leader and self-styled caliph Abu Bakr al Baghdadi. IS backers failed to impose their control on rivals in their original stronghold the city of Darnah in far eastern Libya, and were forced from the town by a coalition of other Islamists in late 2015. In Benghazi, isolated pockets of IS supporters were besieged and defeated in several areas of the city by various LNA-affiliated forces.

While grappling with western and eastern Libyan forces in parallel attempts to expand their territory elsewhere, IS fighters pressed for control over national oil and water infrastructure assets along the country's central coast in 2016. After related clashes damaged vital national oil infrastructure and Sirte-based IS fighters launched more aggressive attacks to the west, pro-GNA militia forces from Misrata and surrounding areas mobilized to confront the group in and around Sirte. U.S. military support (including airstrikes dubbed Operation Odyssey Lightning) aided these pro-GNA forces' operations from August to December 2016. U.S.-supported Libyan forces succeeded in retaking control of the city, but suffered significant casualties in the process.

In March 2017, U.S. AFRICOM Commander General Waldhauser described IS forces in Libya as scattered and attempting to regroup. He also said that U.S. military support for anti-IS fighters would continue and emphasized the importance of political reconciliation as a prerequisite for lasting security.40 The U.S. Treasury Department sanctioned Libya-based IS financiers in April 2017.41 The Islamic State claimed the May 2017 suicide bombing attack in Manchester, United Kingdom, that involved a British citizen of Libyan descent who had spent time in Libya immediately prior to the bombing. In August, the U.N. Secretary-General described the group as "no longer in control of territory in Libya although it continues to be active within the country."42 In September 2017, U.S. strikes targeted IS personnel and equipment south of Sirte. A Defense Department spokesman said,

"The United States will track and hunt these terrorists, degrade their capabilities and disrupt their planning and operations by all appropriate, lawful and proportional means, including precision strikes against their forces, terror training camps and lines of communications, [and] partnering with Libyan forces to deny safe havens for terrorists in Libya."43

Ansar al Sharia and Other Armed Islamist Groups

Armed Islamist groups in Libya occupy a spectrum that reflects differences in ideology as well as their members' underlying personal, familial, tribal, and regional loyalties. Since the 1990s, the epicenters of Islamist militant activity in Libya have largely been in the eastern part of the country, with communities like the coastal town of Darnah and some areas of Benghazi, the east's largest city, coming under the de facto control of armed Salafi-jihadist groups in different periods since 2011. Some Islamists whose armed activism predates the 2011 revolution, such as members of the Darnah-based Abu Salim Martyrs Brigade, have formed new coalitions to pursue their interests in the wake of the revolution.

The emergence of the Ansar al Sharia organization in 2012 demonstrated the appeal of transnationally minded Salafist-jihadist ideology in Libya, and the group persisted alongside other Islamist and secular militia groups in the Benghazi Revolutionaries' Shura Council (BRSC) in battling LNA forces for control of Benghazi. Ansar al Sharia condemned the military operations against it by Haftar-aligned forces as a "war against the religion and Islam backed by the West and their Arab allies."44 In 2014, the U.S. State Department announced the designation of Ansar al Sharia in Benghazi and Ansar al Sharia in Darnah as FTOs and as SDGT entities under Executive Order 13224.45 The group announced its dissolution in a May 2017 communique.

The relationship between supporters of the Islamic State organization and members of Ansar al Sharia and other Salafist-jihadist groups once seen as aligned with Al Qaeda is unclear. Surviving members of the Islamic State may seek support from members of other Islamist militias that similarly have been defeated by other rivals or excluded from national security bodies under future political arrangements. Ansar al Sharia supporters in Darnah were members of the coalition group that expelled the Islamic State from the city.

Press reports also have suggested that some IS fighters fled Sirte for areas of southwestern Libya, where other Islamist extremist operatives reportedly are active. The region's remote, less governed areas serve as safe havens or transit areas for terrorist and smuggling operations in neighboring Niger and Algeria. The State Department reports that the AQIM-affiliated Al Murabitoun group is active in the area and, in 2015, described the group as "one of the greatest near-term threats to U.S. and international interests in the Sahel, because of its publicly stated intent to attack Westerners and proven ability to organize complex attacks."46

A June 2015 U.S. airstrike in eastern Libya targeted prominent Al Murabitoun figure Mokhtar Belmokhtar, who led the group responsible for the January 2013 attack on the natural gas facility at In Amenas, Algeria, in which three Americans were killed. His death in the June 2015 strike that targeted him has not been confirmed, and local allies denied he was killed.47 A French air strike reportedly again targeted Belmokhtar in late 2016, but his death has not been publicly confirmed. Observers note that in early 2017, in a video announcement of a merger among four jihadist networks active in Mali, Al Murabitoun was represented by one of Belmokhtar's deputies.48

Migration and Trafficking in Persons

Conflict and weak governance have transformed Libya into a major staging area for the transit of non-Libyan migrants seeking to reach Europe and have encouraged increasing outflows of migrants present in Libya since mid-2014. Libya is a haven for criminal groups and trafficking networks that seek to exploit such migrants. Data collected by migration observers and immigration officials suggest that many migrants from sub-Saharan Africa transit remote areas of southwestern and southeastern Libya to reach coastal urban areas where onward transit to Europe is organized. Others, including Syrians, enter Libya from neighboring Arab states seeking onward transit to refuge in Europe.

A patchwork of Libyan local and national authorities and nongovernmental entities assume responsibility for responding to various elements of the migrant crisis, including the provision of humanitarian assistance and medical care, the patrol of coastal and maritime areas, and law enforcement efforts targeting migrant transport networks. Violence and insecurity in Libya complicate international attempts to assist Libyan partners in these efforts and to improve coordination among Libyan stakeholders. Reports suggest that many migrants transiting Libya are subject to difficult living conditions, their human rights are frequently violated, and they remain vulnerable to violence at the hands of armed groups, smugglers, and interim authorities. UNHCR is also concerned about those displaced inside the country due to fighting and its inability to register and assist refugees and asylum seekers.

The State Department's 2016 Trafficking in Persons report designated Libya as a "special case" in light of its weak governance and ongoing conflict. The report said that the Bayda-based, HOR-affiliated government in place for much of 2015 "lacked the institutional capacity, resources, and political will to prevent human trafficking." According to the report, Libya is "a destination and transit country for men and women from sub-Saharan Africa and Asia subjected to forced labor and sex trafficking, and there are reports of children being subjected to recruitment and use by armed groups within the country." The report notes that "widespread insecurity driven by militias, civil unrest, and increased lawlessness" limits the availability of accurate information on human trafficking in the country.

In May 2015, the European Union decided to create a naval force (EUNAVFOR MED Operation Sophia) "to break the business model of smugglers and traffickers ... in the Southern Central Mediterranean and in partnership with Libyan authorities."49 The force was inaugurated in June 2015 and is now operational. In October 2015, the U.N. Security Council adopted Resolution 2240, conditionally authorizing member states to inspect and seize vessels on the high seas off the coast of Libya suspected of involvement in migrant smuggling or human trafficking.

In mid-2016, European officials authorized two further tasks for the force: training the Libyan coast guard and navy, and contributing to the enforcement of the United Nations arms embargo, as authorized by Resolution 2292 and extended by Resolution 2357. Coast guard training began in October 2016, and EUNAVFOR MED forces periodically seize weapons on the high seas in support of the arms embargo. As of June 2017, 25 EU member states supported the Rome-based EU mission, and it had saved more than 37,000 lives at sea.50 In April 2017, the EU Trust Fund for Africa announced a €90 million program to better protect migrants along the central Mediterranean route and to provide related management assistance in Libya.

Concern about migrant attempts to cross the Mediterranean Sea from Libya has grown since the European Union reached an agreement with Turkey in March 2016 to restrict passage from Turkey to Greece. The International Organization for Migration (IOM) reported in January 2017 that arrivals to Italy by sea in 2016 were slightly higher than arrivals to Greece by sea in 2016.51 In total, more than 181,000 migrants arrived by sea to Italy in 2016, and at least 4,576 died in transit. IOM estimates that 2016 was the deadliest year for migrants ever recorded in the Mediterranean.

As of September 27, 2017, at least 104,082 migrants had arrived by sea to Italy, and at least 2,471 had died at sea.52 This represents an approximately 20 percent reduction in arrivals and deaths compared to the same period in 2016, which observers attribute to new efforts by Italian and European Union authorities to work with government and nongovernment figures inside Libya to prevent migrant departures and patrol coastal waters.53 Some critics of the new European approaches allege that the policies provide financial benefit and bestow political importance on unaccountable local militia groups, who may threaten the human right and security of migrants.54

U.S. Policy, Assistance, and Military Action

Terrorist organizations active in Libya and the weak and fractious nature of Libya's national security bodies and government institutions pose a dual risk to U.S. and international security. U.S. policy initiatives to address these challenges evolved in 2016, with Obama Administration officials engaged in efforts to build consensus while threatening to sanction and isolate "spoilers." Libyan sacrifices and U.S. military strikes succeeded in ending IS control over significant territory in Libya during 2016, but little progress was made toward political reconciliation. The Trump Administration has maintained U.S. recognition of the GNA and signaled continuing interest in providing U.S. foreign aid and security assistance to support Libya's transition.55 Current U.S. efforts focus on supporting the implementation of the U.N. Action Plan and preventing Libyan territory from being used to support terrorist attacks.

U.S. diplomats were less visibly involved in dialogue negotiations in early 2017, but in May 2017, U.S. Ambassador to Libya Bodde and U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM) Commander General Waldhauser visited Tripoli and remain engaged with various Libyan leaders. While in Tripoli, in May, they restated U.S. support for the GNA, called for reconciliation among Libyans, and discussed "potential future defense institution building efforts and security force assistance."56 The Trump Administration has not named a new Special Envoy for Libya, and in August, Secretary of State Tillerson notified Congress of the State Department's proposal to remove the title and position of the special envoy and shift the functions to the Bureau of Near Eastern Affairs. As noted above, the U.S. military has conducted periodic strikes against Islamic State targets in 2017 and continues to monitor the security situation.

Libya is among the countries identified in Executive Order 13780, which restricts the entry of nationals of certain countries to the United States, with some exceptions. In September 2017, the Trump Administration issued further guidance on the entry restrictions, and suspended the entry of Libyan nationals as immigrants and non-immigrants in certain visa classes (see "Travel Restrictions" below).57

Counterterrorism Policy and Security Sector Assistance

U.S. officials have acknowledged the security risks posed by instability in post-Qadhafi Libya, and U.S. security agencies have acted to degrade the capabilities of terrorist organizations and assess the needs of nascent partner forces since 2011. Periodic U.S. airstrikes targeted senior terrorist leaders and groups from 2015 through September 2017.58 In early 2016, statements by U.S. officials began signaling that U.S. security concerns about the Islamic State presence in Libya had intensified, and that additional U.S. military action against IS targets might proceed even if political consensus among Libyans remained elusive.59 GNA and U.S. officials downplayed the likelihood of intervention in some public remarks, but U.S. military personnel were deployed in small numbers to Libya to liaise with potential partner forces.60 On August 1, GNA Presidency Council Chairman Al Sarraj stated that he had requested U.S. military assistance in combatting the Islamic State organization in and around Sirte on behalf of GNA-aligned forces fighting there. U.S. strikes began on August 1, and as of December 2016, Islamic State forces were significantly degraded and evicted from the city by U.S.-backed Libyan forces.

The Trump Administration shares the Obama Administration's view that executive authority for U.S. strikes against the Islamic State in Libya is authorized by, inter alia, the 2001 Authorization for the Use of Military Force. U.N. Security Council Resolutions 2259 and 2278 state the Council's recognition of "the need to combat by all means, in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations and international law, including applicable international human rights, refugee and humanitarian law, threats to international peace and security caused by terrorist acts, including those committed by groups proclaiming allegiance to ISIL in Libya."61 These resolutions and Resolution 2362 of June 2017 urge Member States to assist the GNA in responding to threats to Libyan security and to provide support in its fight against the Islamic State and other extremist groups upon its request.

In conjunction with military strikes, the U.S. government has worked with GNA officials and other Libyan security figures to determine the scope of their need for potential security assistance.62 AFRICOM has geographic responsibility for Libya, and has engaged with European partners in planning for security assistance to the GNA.63 U.S. defense officials have said that containing instability in Libya is one of five broad lines of effort identified in AFRICOM's five-year plans, and the Defense Department's FY2018 request includes requests for security assistance funding for programs in the AFRICOM area of responsibility that may benefit Libyan entities or address threats emanating from Libya through partnership with neighboring countries. The FY2017 National Defense Authorization Act authorized the provision of border security assistance to Tunisia and Egypt (Section 1294 of P.L. 114-328).

Table 2. Defense Department Regional Counterterrorism and AFRICOM Security Cooperation Funding, FY2015-2018

$, millions

|

Account |

FY2015 Actual |

FY2016 Actual |

FY2017 Request |

FY2018 Request |

|

Counterterrorism Partnerships Fund (Sahel/Maghreb Region) |

113 |

105 |

125 |

- |

|

DSCA Security Assistance (AFRICOM) |

- |

- |

- |

300 |

Source: Defense Department appropriations requests.

Notes: Programs funded under these initiatives benefit multiple countries and may not be designed wholly or in substantial part to address Libya-specific concerns.

Previous State Department and Defense Department plans to develop a Libyan General Purpose Force (GPF) to serve as the nucleus of new national security forces were shelved as conflict broke out among Libyans in 2014.64 U.S. and European efforts to provide organizational assistance and training to Libyan security ministry personnel prior to the U.S. withdrawal reportedly were hindered by security conditions in Libya and complicated by requirements to address Libyans' concerns about proportional local and regional representation in training efforts. Some Libyan recruits sent to the United Kingdom and Jordan for training also were involved in security incidents in those countries: these incidents have raised questions about the viability of external security training programs for Libyan personnel.

The GPF experience may inform any potential U.S. assistance to vetted Libyan forces and/or to the Presidential Guard Force being established by the GNA Presidency Council with French support to provide security for government institutions and infrastructure.65 Since March 2016, the GNA's establishment in Tripoli has been facilitated by security arrangements negotiated with local militias in part by the United Nations Support Mission in Libya. The GNA Presidency Council's critics have described it as being at the mercy of western Libyan militia groups,66 while simultaneously questioning the council's mandate to create any new legitimate security forces until broader political questions are settled. As discussed above (see "The Skhirat Agreement and the Government of National Accord"), Libyan factions are discussing security sector command arrangements now in U.N.-sponsored talks.

Travel Restrictions

Libya is among the countries identified in Executive Order 13780 of March 2017, which restricts the entry of nationals of certain countries to the United States, with some exceptions. In September 2017, the Trump Administration issued further guidance on the entry restrictions, and suspended the entry to the United States of Libyan nationals as immigrants and non-immigrants in certain visa classes.67 The Administration's fact sheet on the changes states:

Although it is an important partner, especially in the area of counterterrorism, the government in Libya faces significant challenges in sharing several types of information, including public-safety and terrorism-related information; has significant inadequacies in its identity-management protocols; has been assessed to be not fully cooperative with respect to receiving its nationals subject to final orders of removal from the United States; and has a substantial terrorist presence within its territory. Accordingly, the entry into the United States of nationals of Libya, as immigrants, and as nonimmigrants on business (B-1), tourist (B-2), and business/tourist (B-1/B-2) visas, is suspended.68

The United States issued 1,445 such B-1, B-2, and B1/B-2 visas to Libyan nationals in FY2016, which was approximately 62 percent of the total number of U.S. visas issued for Libyans.69 From March through August 2017, the United States issued 627 nonimmigrant visas to Libyan nationals.

On September 27, authorities in eastern Libya announced they plan to institute a policy of "reciprocity," calling the U.S. decision a "dangerous escalation, which puts Libyan citizens in one basket with the terrorists the army fights."70

Foreign Assistance Programs

From 2011 through 2014, U.S. engagement in Libya shifted from immediate conflict-related humanitarian assistance to focus on transition assistance and security sector support. More than $25 million in USAID-administered programs funded through the Office of Transition Initiatives, regional accounts, and reprogrammed funds were identified between 2011 and 2014 to support the activities of Libyan civil society groups and provide technical assistance to Libya's nascent electoral administration bodies (see Appendix B).

The security-related withdrawal of some U.S. personnel from Libya in the wake of the 2012 Benghazi attacks temporarily affected the implementation and oversight of U.S.-funded transition assistance programs. U.S. security assistance programs also were disrupted, but some assistance programs were reinstated by late 2013. The 2014 withdrawal of U.S. personnel from the country closed the initial chapter of direct post-Qadhafi engagement, but U.S. personnel have remained engaged through liaison programs administered from outside the country. The U.S. country team for Libya operates from the Libya External Office (LEO) at U.S. Embassy Tunis in Tunisia. As of 2017, U.S. assistance programs are implemented by LEO personnel and via the USAID Middle East Regional Platform office in Frankfurt, Germany.

Despite these challenges, Administration officials remain committed to providing transition support to Libyans and have notified Congress of planned aid obligations in 2017. The Trump Administration has requested $31 million in foreign operations funding for Libya programming in FY2018 (see Table 3 below).

|

Account |

FY2015 Actual |

FY2016 Actual |

FY2017 Request |

FY2018 Request |

|

|

Bilateral Foreign Assistance |

|||||

|

Economic Support Fund (ESF) |

19.2a |

10 |

15 |

23 |

|

|

International Narcotics Control and Law Enforcement (INCLE) |

1.987 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Nonproliferation, Antiterrorism, Demining and Related Programs (NADR) |

3.5 |

6.5 |

4.5 |

7 |

|

|

International Military Education and Training (IMET) |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

Bureau of Conflict and Stabilization Operations Funds |

2.5 |

- |

- |

- |

|

Source: State Department appropriations requests and notifications FY2015-FY2018; and, Explanatory Statement for Division K of P.L. 114-113, the FY2016 Consolidated Appropriations Act.

Notes: Amounts are subject to change. Funds from centrally managed programs, including the Middle East Partnership Initiative (MEPI), Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor (DRL) Office of Global Programming, and USAID Office of Transition Initiatives (OTI) also benefit Libyans. State and USAID may also program resources from the Migration and Refugee Assistance (MRA) and International Disaster Assistance (IDA) humanitarian accounts in Libya. Middle East Regional programs using ESF monies are not included.

a. Includes ESF and ESF-OCO notified to Congress in 2016 to support Libya programs.

In recent years, Congress has enacted appropriations legislation requiring the Administration to certify Libyan cooperation with efforts to investigate the 2012 Benghazi attacks and to submit detailed spending and vetting plans in order to obligate appropriated funds.71 Congress also has prohibited the provision of U.S. assistance to Libya for infrastructure projects "except on a loan basis with terms favorable to the United States." Pending foreign operations legislation for FY2018 would carry forward current terms and conditions on U.S. assistance to Libya (Section 7041(f) of Division G of H.R. 3354 and Section 7041(f) of S. 1780).

Division B of the December 2016 continuing resolution (P.L. 114-254) provided additional overseas contingency operations assistance and operations funding to the State Department and USAID, some of which is supporting post-IS stabilization efforts in Libya and may facilitate the eventual return of U.S. government personnel to the country.

Since 2016, the executive branch has notified Congress of planned programs to continue to engage with Libyan civil society organizations, support multilateral bodies engaged in Libyan stabilization efforts, and build the capacity of municipal authorities, electoral administration entities, and the emerging GNA administration. These notifications include, but are not limited to

- $64.5 million to support the continuation of USAID's Office of Transition Initiatives and other USAID good governance and electoral support programs;

- $1.9 million in Middle East Partnerships Initiative (MEPI) civil society support programming;

- $4 million for the United Nations Development Program Stabilization Facility for Libya;72

- $10 million for U.S. support to UNSMIL and governance programs in support of the GNA;

- $4 million for third-party monitoring of U.S. government Libya programs and for reconciliation, transitional justice, and accountability programming.

U.S. contributions to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs 2016 Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP) for Libya included $5.6 million in funding identified by the State Department Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration (PRM) and USAID's Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance (OFDA). The 2016 plan was 38.9% funded at year's end. In FY2017, the United States has provided $7.7 million for humanitarian activities in Libya.73 The 2017 U.N. HRP seeks $151 million, of which 50.2% was funded as of September 2017.74

Outlook and Issues for Congress

Terrorist threats, Libyans' divisive political competition, and, since mid-2014, outright conflict between rival groups have prevented U.S. officials from developing robust partnerships and assistance programs in post-Qadhafi Libya. The shared desire of the U.S. government and other international actors to empower an inclusive government and rebuild Libyan state security forces has been confounded by the strength of armed nonstate groups, weak institutions, and a fundamental lack of political consensus among Libya's interim leaders, especially regarding security issues. Control over national institutions, territory, and key energy infrastructure continues to define the balance of power in Libya. To the extent that these factors define the prospects for governance and economic viability, they are likely to remain objects of intense competition.

The 2012 attacks in Benghazi (see Appendix C), the deaths of U.S. personnel, the emergence of terrorist threats on Libyan soil, and internecine conflict among Libyan militias have reshaped debates in Washington about U.S. policy toward Libya. Following intense congressional debate over the merits of U.S. and NATO military intervention in Libya in 2011, many Members of Congress welcomed the announcement of Libya's liberation, the formation of the interim Transitional National Council government, and the July 2012 national General National Congress election. Some Members also expressed concern about security in the country, the proliferation of weapons, and the prospects for a smooth political transition. The breakdown of the transition process in 2014 and the outbreak of conflict amplified these concerns, with the subsequent emergence and strengthening of Islamic State supporters in Libya compounding congressional apprehension about the implications of continued instability in the country.

Prior to the escalation of conflict in May 2014, some Libyans had questioned the then-interim government's decision to seek foreign support for security reform and transition guidance, while some U.S. observers had questioned Libya's need for U.S. foreign assistance given its oil resources and relative wealth. During subsequent fighting, some Libyans have vigorously rejected others' calls for international support and assistance and traded accusations of disloyalty and treason in response to reports of partnership with foreign forces. These dynamics raise questions about the potential viability of the U.S. partnership approach, which has sought to build Libyan capacity, coordinate international action, and leverage Libyan financial resources to meet shared objectives and minimize the need for direct U.S. involvement. Some Libyan actors appear to view offers of external assistance and threats of external sanctions in zero-sum terms, despite assurances that third parties seek to support inclusive, consensus arrangements.

The executive branch and Congress appear to have reached a degree of consensus regarding limited security and transition support programs in Libya, some of which responded to specific U.S. security concerns about unsecured weapons, terrorist safe havens, and border security. Given that U.S. military involvement in Libya deepened in 2016 to combat the Islamic State and may expand further to provide support to the national security forces of an emergent Government of National Accord, Congress may choose to reexamine the basic terms of any new U.S.-Libyan cooperation proposed by the Trump Administration. In the meantime, Congress also may choose to conduct oversight of ongoing U.S. diplomacy and assistance programs or examine criteria for the potential resumption of U.S. diplomatic operations in Libya.

In some cases where the U.S. government has sought Libyan government action on priority issues, especially in the counterterrorism sector, U.S. officials have weighed choices over whether U.S. assistance can build sufficient Libyan capacity quickly and cheaply enough. U.S. officials also have considered whether interim leaders are appropriate or reliable partners for the United States and how U.S. action or assistance might affect Libyan politics. In some cases, such as with the threat posed by the Islamic State, U.S. officials have debated when threats to U.S. interests require immediate, direct U.S. action. With Islamic State forces degraded and rivalries among Libyan factions persistent, these questions continue to apply to debates about the future of U.S. assistance plans.

As noted above, the 2017 U.S. AFRICOM Posture Statement concludes that "the instability in Libya and North Africa may be the most significant, near-term threat to U.S. and allies' interests" in Africa. The statement describes "stability in Libya" as "a long-term proposition requiring strategic patience," and states that "Libya's absorption capacity for international support remains limited, as is our ability to influence political reconciliation between competing factions, particularly between the GNA and the House of Representatives."

The failure of U.N.-led reconciliation efforts among Libyans may present U.S. decisionmakers with hard choices about how best to mitigate threats emanating from the country in the continuing absence of a viable, legitimate national government. Possible questions before the United States may include

- whether or how to use existing sanctions provisions against parties seen as obstructing progress toward a GNA agreement;

- whether or how to continue to intervene militarily against the Islamic State and other extremist groups;

- whether or how to respond to interventions by other third parties, including Russia;

- what degree of support, if any, to provide to emergent GNA-affiliated national security forces (particularly in the absence of formal political acceptance of the GNA by the HOR);

- whether or how to respond in the event of any military clashes between rival Libyan factions that involve groups that have received U.S. assistance; and

- whether and how to enforce U.N. Security Council provisions regarding the export of oil, the enforcement of the arms embargo, and the application of sanctions measures.

In the interim, Members of Congress may engage Administration officials (1) to refine the scope and content of U.S. programs proposed to support the Government of National Accord and other Libyans; (2) regarding U.S. contingency planning for the possibility that other third parties may intervene more forcefully in Libya; and (3) regarding the possibility that negotiations among Libyans could fail to bring their conflicts to a prompt close.

Appendix A. Libyan History, Civil War, and Political Change

The North African territory that now composes Libya has a long history as a center of Phoenician, Carthaginian, Greek, Roman, Berber, and Arab civilizations. Modern Libya is a union of three historically distinct regions—northwestern Tripolitania, northeastern Cyrenaica or Barqa, and the more remote southwestern desert region of Fezzan. In the 19th century, the Ottoman Empire struggled to assert control over Libya's coastal cities and interior. Italy invaded Libya in 1911 on the pretext of liberating the region from Ottoman control. The Italians subsequently became mired in decades of colonial abuses against the Libyan people and faced a persistent anticolonial insurgency. Libya was an important battleground in the North Africa campaign of the Second World War and emerged from the fighting as a ward of the Allied powers and the United Nations.

On December 24, 1951, the United Kingdom of Libya became one of Africa's first independent states. With U.N. supervision and assistance, a Libyan National Constituent Assembly drafted and agreed to a constitution establishing a federal system of government with central authority vested in King Idris Al Sanussi. Legislative authority was vested in a Prime Minister, a Council of Ministers, and a bicameral legislature. The first parliamentary election was held in February 1952, one month after independence. The king banned political parties shortly after independence, and Libya's first decade was characterized by continuous infighting over taxation, development, and constitutional powers.

In 1963, King Idris replaced the federal system of government with a unitary monarchy that further centralized royal authority, in part to streamline the development of the country's newly discovered oil resources. Prior to the discovery of marketable oil in 1959, the Libyan government was largely dependent on economic aid and technical assistance it received from international institutions and through military basing agreements with the United States and United Kingdom. The U.S.-operated air base at Wheelus field outside of Tripoli served as an important Strategic Air Command base and center for military intelligence operations throughout the 1950s and 1960s. Oil wealth brought rapid economic growth and greater financial independence to Libya in the 1960s, but the weakness of national institutions and Libyan elites' growing identification with the pan-Arab socialist ideology of Egyptian leader Gamal Abdel Nasser contributed to the gradual marginalization of the monarchy. Popular criticism of U.S. and British basing agreements grew, becoming amplified in the wake of Israel's defeat of Arab forces in the 1967 Six Day War. King Idris left the country in mid-1969 for medical reasons, setting the stage for a military coup in September, led by a young, devoted Nasserite army captain named Muammar al Qadhafi.

The United States did not actively oppose the coup, as Qadhafi and his co-conspirators initially presented an anti-Soviet and reformist platform. Qadhafi focused intensely on securing the immediate and full withdrawal of British and U.S. forces from military bases in Libya, which was complete by mid-1970. The new government also pressured U.S. and other foreign oil companies to renegotiate oil production contracts, and some British and U.S. oil operations eventually were nationalized. In the early 1970s, Qadhafi and his allies gradually reversed their stance on their initially icy relationship with the Soviet Union and extended Libyan support to revolutionary, anti-Western, and anti-Israeli movements across Africa, Europe, Asia, and the Middle East. These policies contributed to a rapid souring of U.S.-Libyan political relations that persisted for decades and was marked by multiple military confrontations, state-sponsored acts of Libyan terrorism against U.S. nationals, covert U.S. support for Libyan opposition groups, Qadhafi's pursuit of weapons of mass destruction, and U.S. and international sanctions.

Qadhafi's policy reversals on WMD and terrorism led to the lifting of international sanctions in 2003 and 2004, followed by economic liberalization, oil sales, and foreign investment that brought new wealth to some Libyans. After U.S. sanctions were lifted, the U.S. business community gradually reengaged amid continuing U.S.-Libyan tension over terrorism concerns that were finally resolved in 2008. During this period of international reengagement, political change in Libya remained elusive. Government reconciliation with imprisoned Islamist militants and the return of some exiled opposition figures were welcomed by some observers as signs that suppression of political opposition had softened. The Qadhafi government released dozens of former members of the Al Qaeda-affiliated Libyan Islamist Fighting Group (LIFG) and the Muslim Brotherhood from prison in the years prior to the revolution as part of its political reconciliation program. The George W. Bush Administration praised Qadhafi's cooperation with U.S. counterterrorism efforts against Al Qaeda and the LIFG.

Qadhafi's international rehabilitation coincided with new steps by some pragmatic government officials to maneuver within so-called "red lines" and propose minor reforms. However, the shifting course of those red lines increasingly entangled would-be reformers in the run-up to the outbreak of unrest in February 2011. Ultimately, inaction on the part of the government in response to calls for guarantees of basic political rights and for the drafting of a constitution suggested a lack of consensus, if not outright opposition to meaningful change among hardliners. This inaction set the political stage for the revolution that overturned Qadhafi's four decades of rule and led to his grisly demise in October 2011.