Introduction

Autonomous vehicles, which would carry out many or all of their functions without the intervention of a driver, may bring sweeping social and economic changes in their wake. The elderly, disabled Americans, urban residents, and those who do not own a car may have new travel options. Travel on public roads and highways could become less congested. Highway travel could become safer as well: U.S. roadway fatalities rose in 2015 and 2016, the first annual increases in more than 50 years,1 and a study by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) has shown that 94% of crashes are due to human errors2 that autonomous vehicles could reduce. As a U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) report noted, highly automated vehicles "hold a learning advantage over humans. While a human driver may repeat the same mistakes as millions before them, a [highly automated vehicle] can benefit from the data and experience drawn from thousands of other vehicles on the road."3

Congressional committees have held numerous hearings on federal policy regarding automated vehicles, and have debated changes in federal regulation to encourage vehicular innovation while protecting passenger safety. In July 2017, the House Energy and Commerce Committee unanimously ordered to be reported the first major legislation on autonomous vehicles (H.R. 3388); the House of Representatives passed that legislation by voice vote on September 6, 2017. The bill has been referred to the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation; members of that committee have issued principles to guide them in developing similar legislation.

Technology of Autonomous Vehicles

The technologies used in autonomous vehicles are very different from the predominantly mechanical, driver-controlled technology of the 1960s, when the first federal vehicle safety laws were enacted. Increasingly, vehicles can be controlled through electronics, requiring little human involvement. Performance can be altered via over-the-air software updates. A range of advanced driver assistance systems is being introduced to motor vehicles, many of them bringing automation to vehicular functions once performed only by the driver. These features automate lighting and braking, connect the car and driver to the Global Positioning System (GPS) and smartphones, and keep the vehicle in the correct lane. Three forces drive motor vehicle innovation:

- technological advances enabled by new materials and more powerful, compact electronics;

- consumer demand for telecommunications connectivity and new types of vehicle ownership and ridesharing; and

- regulatory mandates pertaining to emissions, fuel efficiency, and safety.

Increasingly, such innovations are being combined as manufacturers produce vehicles with higher levels of automation. Vehicles do not fall neatly into two categories of "automated" and "nonautomated," because all of today's motor vehicles have some element of automation.

The Society of Automotive Engineers International (SAE), an international standards-setting organization, has developed six categories of vehicle automation—ranging from a human driver doing everything to automated systems performing all the tasks once performed by a driver. This classification system (Table 1) has been adopted by DOT to foster standardized nomenclature to aid clarity and consistency in discussions about vehicle automation and safety.

|

SAE Automation Category |

Vehicle Function |

|

Level 0 |

Human driver does everything. |

|

Level 1 |

An automated system in the vehicle can sometimes assist the human driver conduct some parts of driving. |

|

Level 2 |

An automated system can conduct some parts of driving, while the human driver continues to monitor the driving environment and performs most of the driving. |

|

Level 3 |

An automated system can conduct some of the driving and monitor the driving environment in some instances, but the human driver must be ready to take back control if necessary. |

|

Level 4 |

An automated system conducts the driving and monitors the driving environment, without human interference, but this level operates only in certain environments and conditions. |

|

Level 5 |

The automated system performs all driving tasks, under all conditions that a human driver could. |

Source: DOT and NHTSA, Federal Automated Vehicles Policy, September 2016, p. 9, https://www.transportation.gov/AV/federal-automated-vehicles-policy-september-2016.

Note: SAE is the Society of Automotive Engineers International, http://www.sae.org.

Vehicles sold today are in levels 1 and 2 of SAE's automation rating system. Views differ as to how long it may take for full automation to become standard. Some forecast market-ready autonomous vehicles at levels 3 to 5 within five years.4 Others argue that it will take much longer, as more testing, regulation, and policy work should be done before autonomous vehicles beyond level 2 are widely deployed.5

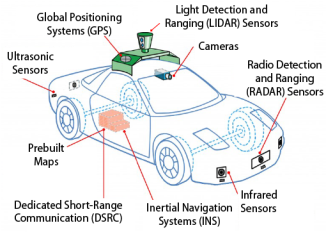

Technologies that could guide an automated vehicle (Figure 1) include a wide variety of electronic sensors that would determine the distance between the vehicle and obstacles; detect lane markings, pedestrians, and bicycles; park the vehicle; use GPS, inertial navigation, and a system of built-in maps to guide the vehicle direction and location; employ cameras that provide 360-degree views around the vehicle; and use dedicated short-range communication (DSRC) to monitor road conditions, congestion, crashes, and possible rerouting. These technologies are being offered in various combinations on vehicles currently on the market, while manufacturers study how to combine them in vehicles that could safely transport passengers without drivers.

|

|

Source: CRS, based on "Autonomous Vehicles" fact sheet, Center for Sustainable Systems, University of Michigan. |

While private-sector development has focused on vehicle equipment, federal and academic researchers, along with industry, have spent over a decade developing complementary sensor technologies that could improve safety and vehicle performance. These include vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V) and vehicle-to-infrastructure (V2I) capabilities—often referred to with the composite term V2X.

V2X technology relies on communication of information to warn drivers about dangerous situations that could lead to a crash, using DSRC to exchange messages about vehicles' speeds, braking status, stopped vehicles ahead, or blind spots to warn drivers so they can take evasive action. V2X messages have a range of 300 meters (a fifth of a mile)—up to twice the distance of onboard sensors—cameras, and radar.6 These radio messages can "see" around corners and through other vehicles.

NHTSA has evaluated V2X applications and estimates that just two of them could reduce the number of crashes by 50%: intersection movement assist warns the driver when it is not safe to enter an intersection, and left turn assist warns a driver when there is a strong probability of colliding with an oncoming vehicle when making a left turn. V2V communications may also permit technologies such as forward collision warning, blind spot warning, and do-not-pass warnings. NHTSA estimated in 2014 that installing V2V communications capability will cost about $350 per vehicle.7

Federal Regulatory Issues

DOT has issued two reports on federal regulatory issues with regard to autonomous vehicles, based on consultations with industry, technology and mobility experts, state governments, safety advocates, and others. DOT anticipates that it will continue to issue annual updates on federal regulatory guidance, in light of the pace of autonomous vehicle innovation.

The first report issued by DOT, Federal Automated Vehicles Policy,8 laid the foundation for regulation and legislation by clarifying DOT's thinking in four areas:

- a set of guidelines outlining best practices for autonomous vehicle design, testing, and deployment;

- a model state policy that identifies where new autonomous vehicle-related issues fit in the current federal and state regulatory structures;

- a streamlined review process to expedite requests for DOT regulatory interpretations to spur autonomous development; and

- identification of new tools and regulatory structures for NHTSA that could aid in autonomous deployment, such as expanded exemption authority and premarket testing to assure that autonomous vehicles will be safe.

Guidelines

The 2016 guidelines identified 15 practices and procedures that DOT expected manufacturers, suppliers, and service providers—such as driverless taxi companies—to follow in testing autonomous vehicles.9 It was expected that the data generated from this research would be widely shared with government and the public while still respecting competitive interests.

Manufacturers, researchers, and service providers were urged to ensure that their test vehicles meet applicable NHTSA safety standards10 and that their vehicles be tested through simulation, on test tracks, or on actual roadways. To assist in the regulatory oversight, NHTSA requested each entity testing autonomous vehicles to submit Safety Assessment letters that will outline how it is meeting the guidelines, addressing such issues as data recording, privacy, system safety, cybersecurity, and crashworthiness. DOT specified that vehicle software must be capable of being updated through over-the-air means (similar to how smartphones are currently updated), so improvements can be diffused quickly to vehicle owners.11

Model State Policy

Any vehicle operating on public roads is subject to dual regulation by the federal government and the states in which it is registered and driven. Traditionally, NHTSA has regulated auto safety, while states have licensed automobile drivers and established traffic regulations.12 DOT's 2016 report clarified and restated that division for the transition to fully autonomous vehicles where the automobile is the driver.

The model state policy, developed by NHTSA in concert with the American Association of Motor Vehicle Administrators and other safety advocates, suggested state roles and procedures,13 including administrative issues (designating a lead state agency for autonomous vehicle testing), an application process for manufacturers that want to test vehicles on state roads, coordination with local law enforcement agencies, changes to vehicle registration and titling, and liability and insurance. Liability may change significantly with autonomous vehicles, as states will have to reconsider the extent to which vehicle owners, operators, passengers, vehicle manufacturers, and component suppliers bear responsibility for accidents when no one is actively driving the vehicle.

Current Federal Regulatory Tools

In addition to its existing authority to issue federal vehicle safety standards and order recalls of defective vehicles, NHTSA has other tools it can use to address the introduction of new technologies: letters of interpretation, exemptions from current standards, and rulemakings to issue new standards or amend existing standards.

NHTSA uses letters of interpretation when it receives requests seeking clarifications of existing law. It may take NHTSA several months or even years to issue a letter of interpretation, which cannot make substantive changes to regulations.

The agency can grant exemptions from safety standards in certain circumstances. They are not granted indefinitely—an exemption may last for two or three years—or for a large number of vehicles.14 The approval process may take months or years. Rulemaking to adopt new standards or modify existing ones generally takes several years and requires extensive public comment periods.

Proposed New Regulatory Tools

Federal Automated Vehicles Policy identified potential new tools and authorities that could affect the way autonomous vehicles are regulated. These included the following:

- Premarket safety assurance tools such as premarket testing, data, and analyses reported by a manufacturer to demonstrate that a new vehicle met standards before being deployed on public roads. The report asserted that some of these tools could be used without new statutory authority.

- Premarket approval authority,15 as distinct from safety assurance as well as from the self-certification process used for the past 50 years.16 The report indicated this could be used to replace self-certification for autonomous vehicles, requiring NHTSA to test prototype vehicles to ensure that they met all federal motor vehicle safety standards. It said NHTSA would need new statutory authority and additional resources to take on certification procedures now handled by manufacturers.

- Imminent hazard authority to permit NHTSA to take immediate action to curtail serious safety risks that could harm the public. The Obama Administration unsuccessfully argued that this new tool be included in the 2015 surface transportation bill.17

- Expanded exemption authority for autonomous vehicles. The report recommended raising the current limit of 2,500 vehicles that can be exempted from federal safety standards in order to provide a larger database of real-world experience for analyzing on-road safety readiness of exempted vehicles. The report described several alternative ways in which an expanded exemption could operate, and noted that "it would be important to guard against overuse of the authority such that exemptions might displace rulemaking as the de facto primary method of regulating motor vehicles and equipment."18

- Enhanced data collection tools allowing NHTSA to utilize the large amounts of data collected by autonomous vehicles. One example would be to employ event data recorders—now used in a limited way on nearly all motor vehicles to record vehicle and driver information in the seconds before a crash—for use in autonomous vehicles to identify safety-related defects. NHTSA said it has the statutory authority now for this tool.

Trump Administration Revises DOT Guidelines

The Trump Administration issued changes to Federal Automated Vehicles Policy on September 12, 2017, announcing at the same time that DOT expects to issue annual automated driving systems (ADS) policy updates in light of the pace of vehicle innovation. The new voluntary guidance, Automated Driving Systems 2.0: A Vision for Safety,19 clarifies for manufacturers, service providers, and states some of the issues raised in the Obama Administration's predecessor report and replaces some parts of the earlier guidance; the new policy recommendations took effect immediately.20 In developing the revised autonomous vehicle policy, DOT evaluated comments, public meeting proceedings, recent congressional hearings, and state activities. Among the clarifications, which affect Level 3 through 5 vehicles, are the following:

Whereas the 2016 DOT report listed 15 vehicle performance guidelines for testing practices and procedures, the 2017 DOT report cites 12, eliminating recommendations concerning privacy; registration and certification; and ethical considerations. A DOT web page notes that "elements involving privacy, ethical considerations, registration, and the sharing of data beyond crash data remain important and are areas for further discussion and research."21

These vehicle performance guidelines, and the manufacturers' compliance with them, which had to be reported to NHTSA in a mandatory Safety Assessment letter under the 2016 policy, have now been made voluntary and no reports are required. Instead, organizations testing autonomous vehicles are encouraged to address the 12 procedures and processes by publishing a voluntary safety self-assessment of how their testing procedures align with NHTSA's recommended procedures, and sharing it with consumers, governments, and the public so a better understanding of autonomous vehicle capabilities is developed.22

The 2016 policy indicated that in the future NHTSA might make these guidelines mandatory and subject to a rulemaking. That language has been replaced with a statement that "assessments are not subject to federal approval."23

The 2017 report provides best practices recommended for state legislatures with regard to Level 3 and 4 vehicles, building on DOT's Model State Policy issued in 2016. DOT notes that it is not necessary that all state laws with regard to autonomous vehicles be uniform, but rather that they "promote innovation and the swift, widespread, safe integration of ADSs."24 In the 2017 report, NHTSA recommends states adopt four safety-related types of legislation covering the following:

- A technology-neutral environment. Legislation proposed in some states would grant motor vehicle manufacturers special standing over other organizations in testing autonomous vehicles, but the 2017 report states that "no data suggests that experience in vehicle manufacturing is an indicator of the ability to safely test or deploy vehicle technology,"25 and DOT counsels that all organizations meeting federal and state "law prerequisites" should be able to test vehicles in that state.

- Licensing and registration procedures.

- Reporting and communications methods for public safety officials.

- Review of traffic laws and regulations that could be barriers to ADS testing and deployment.

Automated Driving Systems 2.0: A Vision for Safety also includes best practices for state highway safety officials, including registration and titling and liability and insurance.26

State Concerns

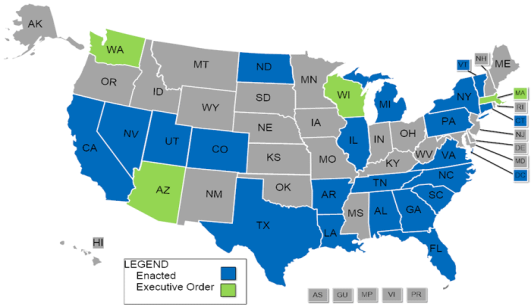

According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, 20 states plus the District of Columbia have enacted legislation related to autonomous vehicles (Figure 2), and related bills have been introduced in 33 states in 2017. DOT's model state policy and H.R. 3388, as passed by the House of Representatives, reflect concerns that the absence of federal regulation covering autonomous vehicles may encourage states to move forward on their own, potentially resulting in diverse and even conflicting state regulations.

State laws with regard to autonomous vehicles vary widely. Florida was the first state to permit anyone with a valid driver's license to operate an autonomous vehicle on public roads, and it does not require an operator to be in the vehicle. In California, the regional Contra Costa Transportation Authority approved the testing on certain public roads of autonomous vehicles not equipped with a steering wheel, brake pedal, or accelerator. A Tennessee law bars local governments from prohibiting the use of autonomous vehicles and established a new vehicle tax. North Dakota and Utah enacted laws to study safety standards and report back to the legislature with recommendations. Michigan enacted several bills in 2016 that permit autonomous vehicles to be driven on public roads, address testing procedures, and establish the American Center for Mobility for testing vehicles.27

|

|

Source: National Conference of State Legislatures, viewed on September 15, 2017, http://www.ncsl.org/research/transportation/autonomous-vehicles-self-driving-vehicles-enacted-legislation.aspx. Note: States in gray have not issued executive orders or enacted legislation on autonomous vehicles. |

Cybersecurity and Data Privacy

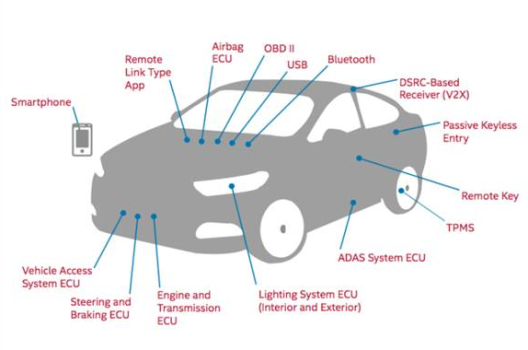

The more automated vehicles become, the more sensors and computer components are employed to provide functions now handled by the driver. Many of these new automated components will generate large amounts of data about the vehicle, its location at precise moments in time, driver behavior, and vehicle performance, thereby opening new portals for possible unauthorized access to vehicle systems and the data generated by them.

Protecting autonomous vehicles from hackers is of paramount concern to federal and state governments, manufacturers, and service providers. A well-publicized hacking of a conventional vehicle by professionals28 demonstrated to the public that such disruptions can occur. Hackers could use more than a dozen portals to enter even a conventional vehicle's electronic systems (Figure 3), including seemingly innocuous entry points such as the airbag, lighting systems, and tire pressure monitoring system (TPMS).29 Requirements that automated vehicles accept remote software updates, so that owners do not need to take action each time software is revised, are in part a response to concerns that security weaknesses be rectified as quickly as possible.

|

|

Source: Tom Huddleston Jr., "This graphic shows all the ways your car can be hacked," Fortune, September 15, 2015, http://fortune.com/2015/09/15/intel-car-hacking/. Note: Graphic courtesy of Intel Corp. |

To address these concerns, motor vehicle manufacturers established the Automotive Information Sharing and Analysis Center (Auto-ISAC),30 which released a set of cybersecurity principles in 2016. DOT's automated vehicle policies address cybersecurity, calling for a product development process that engineers into vehicle electronics a thorough cybersecurity threat mitigation system, and sharing of incidents, threats, and violations to the Auto-ISAC so that the broader vehicle industry can learn from them.

Aside from hackers, many legitimate entities would like to access vehicle data, including the manufacturer, the supplier providing the technology and sensors, the vehicle owner and occupants, urban planners, insurance companies, law enforcement, and first responders (in case of an accident). Relevant types of data include the following:

Vehicle testing crash data. DOT's autonomous vehicle policy reports address how data from vehicle crashes during a test should be handled, with entities conducting the testing adopting best practices established by standard-setting organizations such as the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) and the Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) International. NHTSA recommended that the data from autonomous vehicle crashes be stored and made available for retrieval and shared with the government for crash reconstruction.31

Data Ownership. Current law does not address ownership of most of the data collected by vehicle software and computers. Most new conventional vehicles on the road have an event data recorder (EDR), which captures a limited amount of information about a vehicle, the driver, and passengers in the few seconds before a crash (e.g., speed and use of seat belts). The most recent surface transportation legislation32 enacted the Driver Privacy Act of 2015 to address data ownership with regard to EDRs—establishing that EDR data is property of the vehicle owner—but it does not govern the other types of data that will be accumulated by autonomous vehicles. The National Association of City Transportation Officials has recommended that the federal government identify these data, their ownership, and instances where they should be shared.33

Consumer Privacy. The 2016 DOT report included a section on privacy, but the 2017 DOT report omits that discussion. In the earlier report, DOT discussed elements that testing organizations' policies should include, such as transparency for consumers and owner access to data.34 Separately, two motor vehicle trade associations have developed Privacy Principles for Vehicle Technologies and Services, which are similar to the practices discussed in the 2016 DOT report.35

Educating Motorists and Pedestrians

There may not be a consensus on when large numbers of autonomous vehicles will hit U.S. roads, but whenever that time comes, those vehicles will be a small segment of the more than 264 million passenger cars and light trucks now registered in the United States.36 With Americans keeping their cars for an average of more than 11 years, traditional vehicles are likely to have a highway presence for decades.

Several recent studies and surveys reveal public skepticism about autonomous vehicles. A recent survey by IHS Markit, a market research firm, shows that motorists overwhelmingly approve of some Levels 1 and 2 automated vehicle technologies—such as blind spot detection and automatic emergency braking—but that fully autonomous vehicles are not as popular.37 A similar 2017 study by J.D. Power, a consumer research firm, found that most Americans are becoming more skeptical of self-driving motor vehicle technology, although strong interest exists in some of the elements of autonomy, such as collision protection and driving assistance technologies. The report noted that "automated driving is a new and complex concept for many consumers; they'll have to experience it firsthand to fully understand it."38 The Governors Highway Safety Association also reported on three additional surveys with similar results.39

To address the lack of understanding about autonomous vehicles, the 2017 DOT report calls for major consumer education and training as vehicles are tested and deployed. Organizations testing vehicles are encouraged to "develop, document, and maintain employee dealer, distributor, and consumer education and training programs to address the anticipated differences in the use and operation of ADSs from those of the conventional vehicles that the public owns and operates today."40

DOT underscores the need for a wide range of potential autonomous vehicle users to become familiar before vehicles are sold to consumers, using on- and off-road demonstrations, virtual reality, and onboard vehicle systems. Others have made suggestions for consumer education about autonomous vehicles, including the following:

- the vehicle should let people on the road—including pedestrians—know when a vehicle is in self-driving mode;

- vehicle sales representatives should be trained about the technical aspects of the vehicle and the benefits and risks of such vehicles compared to conventional vehicles; and

- manufacturers should hold training seminars, including crashworthiness and fall back options (should a system fail), with updates as new levels of autonomy are introduced.41

Congressional Action

Committees in the House of Representatives and Senate have held numerous hearings on the technology of autonomous vehicles and possible federal issues that could result from their deployment.

House of Representatives

On September 6, 2017, the House of Representatives passed by voice vote H.R. 3388, the Safely Ensuring Lives Future Deployment and Research In Vehicle Evolution Act—or SELF DRIVE Act. The bill addresses concerns about state action replacing some federal regulation, while also empowering NHTSA to take unique regulatory actions to ensure safety and encouraging innovation in autonomous vehicles. It retains and clarifies the current arrangement of states controlling most driver-related functions and the federal government being responsible for vehicle safety. The major provisions focus on the following:

State Preemption. States would not be allowed to regulate the design, construction, or performance of highly automated vehicles, automated driving systems, or their components unless those laws are identical to federal law.42 The legislation reiterates that vehicle registration, driver licensing, driving education, insurance, law enforcement, and crash investigations should remain in state jurisdiction as long as they do not restrict autonomous vehicle development. H.R. 3388 states that nothing in the preemption section should prohibit states from enforcing their laws and regulations on the sale and repair of motor vehicles.

New Safety Standards. Within two years of enactment, DOT would have to issue a final rule requiring each manufacturer to show how it is addressing safety in its autonomous vehicles, with updates every five years thereafter. DOT would not be allowed to condition vehicle deployment on review of these certificates, however. The regulation establishing the safety assessment certifications would have to specify the testing requirements and data necessary to demonstrate safety in the operation of the autonomous vehicle. In the interim, manufacturers would have to submit safety assessment letters.43

Safety Priority Plan. DOT would be expected to submit a safety priority plan within a year of enactment, indicating which existing federal safety standards must be updated to accommodate autonomous vehicles, the need for new standards,44 and NHTSA's safety priorities for autonomous vehicles and other vehicles.

Cybersecurity. Highly autonomous vehicles will rely on computers, sensors, and cameras to navigate, so cybersecurity protections will be necessary to ensure vehicle performance. The legislation stipulates that no highly autonomous vehicle, or vehicle with partial driving automation, could be sold domestically unless a cybersecurity plan has been developed by the automaker. The plan would have to include

- a written policy on mitigation of cyberattacks, unauthorized intrusions, and malicious vehicle control commands;

- a point of contact at the automaker with cybersecurity responsibilities;

- a process for limiting access to automated driving systems; and

- the manufacturer's plans for employee training and for maintenance of the policies.

Exemption Authority. As recommended in DOT's 2016 Federal Automated Vehicles Policy, the bill would expand DOT's ability to issue exemptions from existing safety standards to encourage autonomous vehicle testing.45 To qualify for an exemption, a manufacturer would have to show that the safety level of the automated vehicle equals or exceeds the safety level of that standard for which an exemption is sought.

Whereas current laws limit exemptions to 2,500 vehicles per manufacturer per year, the bill would phase in increases over four years of up 100,000 vehicles per manufacturer per year. DOT would be directed to establish a publicly available and searchable database of motor vehicles that have been granted an exemption.

Privacy. Before selling highly automated vehicles, manufacturers would be required to develop written privacy plans concerning the collection and storage of data generated by the vehicles, as well as a method of conveying that information to vehicle owners and occupants. However, a manufacturer would be allowed to exclude processes from its privacy policy that encrypt or make anonymous the sources of data. The Federal Trade Commission would be tasked with developing a report for Congress on a number of vehicle privacy issues.

Consumer Information. DOT would be directed to complete a research program within three years that would lay the groundwork for a consumer education program about the capabilities and limitations of highly automated vehicles. DOT would be mandated to issue a regulation requiring manufacturers to explain the new systems to consumers.

Highly Automated Vehicle Advisory Council. A new NHTSA advisory group would be established with up to 30 members from business, academia, states and localities, and labor, environmental, and consumer groups to advise on mobility access for senior citizens and the disabled; cybersecurity; labor, employment, environmental, and privacy issues; and testing and information sharing among manufacturers.

The legislation also addresses several vehicle safety standards not directly related to autonomous vehicles:

Rear Seat Occupant Alert System. In an effort to reduce or eliminate infant fatalities, the bill would direct DOT to issue a final regulation within two years requiring all new passenger vehicles to be equipped with an alarm system to alert the driver to check the back seats after the vehicle's motor or engine is shut off.

Headlamps. DOT would be directed to initiate research into updating motor vehicle safety standards to improve performance and safety, and to revise the standards if appropriate. If NHTSA chooses not to revise the standards, it must report to Congress on its reasoning.

Controversy with the Legislation

Although H.R. 3388 was passed the House of Representatives without objection, several groups have raised specific concerns about the legislation. These groups include the following:

- Five state and local government associations46contend the bill goes beyond the traditional definition of motor vehicle safety and expands federal preemption to "encroach on vehicle operations, currently under states' purview." They argue that this may imply that the federal government "will take on the role of being the sole regulator of vehicle operations." They ask that the legislation reaffirm the traditional state and federal vehicle regulatory roles and provide for state government representation on the Highly Autonomous Vehicle Advisory Council. They also ask that the legislation direct NHTSA to immediately notify state and local officials when it grants an exemption for testing of autonomous vehicles.

- A coalition of seven vehicle safety advocacy groups47 contends that H.R. 3388 "takes an unnecessary and unacceptable hands-off approach to hands-Free driving." The signatories warn that the large number of exemptions that could be permitted by NHTSA could allow "potentially millions of vehicles on America's roads" that do not meet federal safety standards. They are also critical of allowing crashworthiness standards to be relaxed for autonomous vehicles, believe the data collected should be more widely and publicly shared, and contend that the preemption of state authority is too broad, undermining the ability of states to ensure public safety. The group also calls on Congress to provide more NHTSA resources and the inclusion of imminent hazard authority.

- Transportation for America, a nonprofit organization advocating for urban transportation solutions, contends that the legislation was not developed with a broad enough consultation with stakeholders who will be affected by autonomous vehicles. It argues that the new exemption policy may allow too many experimental vehicles on the road, that provisions to require test data sharing with cities, states, and independent researchers are inadequate, and that the preemption provisions will prevent local governments "from managing their own streets."48

Senate

The Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation has not voted on autonomous vehicle legislation, but the committee's chairman and ranking member49 issued a set of principles in June 2017 that may form the basis of future legislation that the committee may consider. Their principles call for legislation that will

- prioritize safety, acknowledging that federal standards will eventually be as important for self-driving vehicles as they are for conventional vehicles;

- promote innovation and address the incompatibility of old regulations written before the advent of self-driving vehicles;

- remain technology-neutral, not favoring one business model over another;

- reinforce separate but complementary federal and state regulatory roles;

- strengthen cybersecurity so that manufacturers address potential vulnerabilities before occupant safety is compromised; and

- educate the public through government and industry efforts so that the differences between conventional and self-driving vehicles are understood.