Introduction

Social Security provides dependent benefits and survivors benefits, sometimes collectively referred to as auxiliary benefits, to the spouses, former spouses, widow(er)s, children, and parents of retired, disabled, and deceased workers.1 Auxiliary benefits are based on the work record of the household's primary earner.

Social Security spousal benefits (i.e., benefits for a wife or husband of the primary earner) are payable to the spouse or divorced spouse of a retired or disabled worker. Social Security survivor benefits are payable to the survivors of a deceased worker as a widow(er), as a child, as a mother or father of the deceased worker's child(ren), or as a dependent parent of the deceased worker. Although Social Security is often viewed as a program that primarily provides benefits to retired and disabled workers, 34% of new benefit awards in 2015 were made to the dependents and survivors of retired, disabled, and deceased workers.2

Spousal and survivor benefits play an important role in ensuring women's retirement security. However, women continue to be vulnerable to poverty in old age, due to demographic and economic reasons, as well as program design. This report presents the current-law structure of auxiliary benefits for spouses, divorced spouses, and surviving spouses. It makes note of adequacy and equity concerns of current-law spousal and widow(er)'s benefits, particularly with respect to female beneficiaries, and discusses the role of demographics, the labor market, and current-law provisions on adequacy and equity. The report concludes with a discussion of proposed changes to spousal and widow(er) benefits to address these concerns.

Origins of Social Security Auxiliary Benefits

The original Social Security Act of 1935 (P.L. 74-271) established a system of Old-Age Insurance to provide benefits to individuals aged 65 or older who had "earned" retirement benefits through work in jobs covered by the system. Before the Old-Age Insurance program was in full operation, the Social Security Amendments of 1939 (P.L.76-379) extended monthly benefits to workers' dependents and survivors. The program now provided Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI).3

The 1939 amendments established benefits for the following dependents and survivors: (1) a wife aged 65 or older; (2) a child under the age of 18; (3) a widowed mother of any age caring for an eligible child; (4) a widow aged 65 or older; and (5) a surviving dependent parent aged 65 or older.

In its report to the Social Security Board (the predecessor to the Social Security Administration) and the Senate Committee on Finance, the 1938 Social Security Advisory Council justified creating spousal benefits on the grounds of the adequacy of household benefits:

The inadequacy of the benefits payable during the early years of the old-age insurance program is more marked where the benefits must support not only the annuitant himself but also his wife. In 1930, 63.8 per cent of men aged 65 and over were married. Payment of supplementary allowances to annuitants who have wives over 65 will increase the average benefit in such a manner as to meet the greatest social need with the minimum increase in cost. The Council believes that an additional 50 percent of the basic annuity would constitute a reasonable provision for the support of the annuitant's wife.4

The Social Security Board concurred in its own report, which it wrote based on the council's report. The board also found that benefit adequacy was the primary justification for spousal benefits:

The Board suggests that a supplementary benefit be paid for the aged dependent wife of the retired worker which would be related to his old-age benefit. Such a plan would take account of greater presumptive need of the married couple without requiring investigation of individual need.5

Since 1939, auxiliary benefits have been modified by Congress many times, including the expansion of benefits to husbands, widowers, and divorced spouses. The legislative history of auxiliary benefits is outlined in detail in Appendix A.

Auxiliary Benefits

Auxiliary benefits for a spouse, survivor, or other dependent are based on the benefit amount received by a primary earner (an insured worker). The primary earner may receive a Social Security retirement or disability benefit. Social Security retirement benefits are based on the average of a worker's highest 35 years of earnings (less up to 5 years for years of disability) from covered employment. A worker's basic benefit amount (primary insurance amount or PIA) is computed by applying the Social Security benefit formula to the worker's career-average, wage-indexed earnings (average indexed monthly earnings or AIME). The benefit formula replaces a higher percentage of the preretirement earnings of workers with low career-average earnings than for workers with high career-average earnings.

The primary earner's initial monthly benefit is equal to his or her PIA if benefits are claimed at full retirement age (FRA, which ranges from age 65 to age 67, depending on year of birth). A worker's initial monthly benefit will be less than his or her PIA if the worker begins receiving benefits before FRA, and it will be greater than his or her PIA if the worker begins receiving benefits after FRA. The purpose of the actuarial adjustment to benefits claimed before or after FRA is to ensure that the worker receives roughly the same total lifetime benefits regardless of when he or she claims benefits (assuming he or she lives to average life expectancy). For a detailed explanation of the Social Security retired-worker benefit computation, the actuarial adjustment to benefits claimed before or after FRA and other benefit adjustments that may apply, see Appendix B.

Auxiliary benefits are paid to the spouse, former spouse, survivor, child, or parent of the primary earner.6 Auxiliary benefits are determined as a percentage of the primary earner's PIA, subject to a maximum family benefit amount. For example, the spouse of a retired or disabled worker may receive up to 50% of the worker's PIA, and the widow(er) of a deceased worker may receive up to 100% of the worker's PIA. As with benefits paid to the primary earner, auxiliary benefits are subject to adjustments based on age at entitlement and other factors. A basic description of auxiliary benefits is provided in the following sections, with more detailed information provided in Appendix C.

Currently Married or Separated Spouses of Retired or Disabled Workers

Social Security provides a spousal benefit that is equal to 50% of a retired or disabled worker's PIA.7 A qualifying spouse must be at least 62 years old or have a qualifying child (a child who is under the age of 16 or who receives Social Security disability benefits) in his or her care. A qualifying spouse may be either married to or separated from the worker. An individual must have been married to the worker for at least one year before he or she applies for spousal benefits, with certain exceptions. In addition, the worker must be entitled to (generally, collecting) benefits for an eligible spouse to become entitled to benefits.8

If a spouse claims benefits before FRA, his or her benefits are reduced to take into account the longer expected period of benefit receipt. An individual who is entitled to a Social Security benefit based on his or her own work record and to a spousal benefit in effect receives the higher of the two benefits (see "Dually Entitled Beneficiaries" below).

Widow's and Widower's Benefits

Under current law, surviving spouses (including divorced surviving spouses) may be eligible for aged widow(er) benefits beginning at the age of 60. If the surviving spouse has a qualifying impairment and meets certain other conditions, survivor benefits are available beginning at the age of 50. The aged widow(er)'s basic benefit is equal to 100% of the deceased worker's PIA.9

A qualifying widow(er) must have been married to the deceased worker for at least nine months and must not have remarried before the age of 60 (or before age 50 if the widow[er] is disabled).10 Widow(er)s who remarry after the age of 60 (or after age 50 if disabled) may become entitled to benefits based on the prior deceased spouse's work record. Widow[er]s who are caring for children under the age of 16 or disabled may receive survivor benefits at any age and do not have to meet the length of marriage requirement—see "Mother's and Father's Benefits" below.

If an aged widow(er) claims survivor benefits before FRA, his or her monthly benefit is reduced (up to a maximum of 28.5%) to take into account the longer expected period of benefit receipt. In addition, survivor benefits may be affected by the deceased worker's decision to claim benefits before FRA under the widow(er)'s limit provision (see Appendix C). As with spouses of retired or disabled workers, a surviving spouse who is entitled to a Social Security benefit based on his or her own work record and a widow(er)'s benefit receives in effect the higher of the two benefits (see "Dually Entitled Beneficiaries" below).

Mother's and Father's Benefits

Social Security provides benefits to a surviving spouse or divorced surviving spouse of any age who is caring for the deceased worker's child, when that child is either under the age of 16 or disabled. Mother's and father's benefits are equal to 75% of the deceased worker's PIA, subject to a maximum family benefit. There are no length of marriage requirements for mother's and father's benefits, whether the beneficiary was married to, separated from, or divorced from the deceased worker; however, remarriage generally ends entitlement to mother's and father's benefits.

Divorced Spouses' Spousal and Survivor Benefits

Spousal benefits are available to a divorced spouse beginning at the age of 62, if the marriage lasted at least 10 years before the divorce became final and the person claiming spousal benefits is currently unmarried.11 A divorced spouse who is younger than 62 years old is not eligible for spousal benefits even with an entitled child in his or her care. Survivor benefits are available to a divorced surviving spouse beginning at the age of 60 (or beginning at age 50 if the divorced surviving spouse is disabled) if the divorced surviving spouse has not remarried before the age of 60 (or before age 50 if disabled), or if the surviving divorced spouse has an entitled child in his or her care.

Divorced spouses who are entitled to benefits receive the same spousal and survivor benefits as married or separated persons. If a divorced spouse claims benefits before FRA, his or her benefits are reduced to take into account the longer expected period of benefit receipt. In addition, a divorced spouse who is entitled to a Social Security benefit based on his or her own work record and a spousal or survivor benefit receives in effect the higher of the two benefits (see "Dually Entitled Beneficiaries" below).

Data on Duration of Marriages

A divorced person who was married to a primary earner for less than 10 years does not qualify for spousal benefits on that spouse's record (although he or she may qualify for benefits based on his or her own record or on another spouse's record).12 First marriages that end in divorce have a median duration of 8 years.13 Table 1 shows that first marriages occurring from 1960 to 1964 lasted longer than those occurring in subsequent decades. About 83% of women who married for the first time during the early 1960s stayed married for 10 years or longer; however, since the 1970s, about 71%-75% of women's first marriages have lasted for at least 10 years. According to the same source, about 16% of women aged 45-49 in 2009 had been married two or more times.14

Table 1. Percentage Reaching 10th Marriage Anniversary, by Marriage Cohort and Sex, for First Marriages

|

Year of Marriage |

Male |

Female |

||||

|

1960-1964 |

|

|

||||

|

1965-1969 |

|

|

||||

|

1970-1974 |

|

|

||||

|

1975-1979 |

|

|

||||

|

1980-1984 |

|

|

||||

|

1985-1989 |

|

|

||||

|

1990-1994 |

|

|

||||

|

1995-1999 |

|

|

||||

|

2000-2004 |

|

|

Source: Census Bureau, Number, Timing and Duration of Marriages and Divorces: 2009, May 2011, Table 4, http://www.census.gov/prod/2011pubs/p70-125.pdf; and the Congressional Research Service (CRS) calculations from the 2014 Survey of Income and Program Participation Social Security Administration Supplement.

Notes: The Census Bureau has not updated their Number, Timing and Duration of Marriages and Divorces since 2011; data for 1995-2004 are based on CRS calculations from the 2014 Survey of Income and Program Participation Social Security Administration Supplement.

Other data suggest that, for men and women aged 15 to 44 between 2006 and 2010, the probability of a first marriage lasting 10 years or longer was 68%. The probability that a first marriage would remain intact for at least 10 years was 73%, 56%, and 68% for Hispanic, black, and white women, respectively.15

Dually Entitled Beneficiaries

A person may qualify for a spousal or survivor benefit as well as for a Social Security benefit based on his or her own work record (a retired-worker benefit). In such cases, the person in effect receives the higher of the worker benefit and the spousal or survivor benefit. When the person's retired-worker benefit is higher than the spousal or survivor benefit to which he or she would be entitled, the person receives only the retired-worker benefit. Conversely, when the person's retired-worker benefit is lower than the spousal or survivor benefit, the person is referred to as dually entitled and receives the retired-worker benefit plus a spousal or survivor benefit that is equal to the difference between the retired-worker benefit and the full spousal or survivor benefit. In essence, the person receives a total benefit amount equal to the higher spousal benefit.

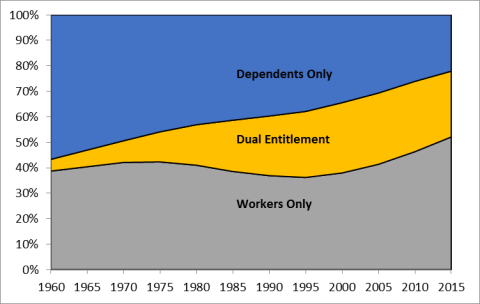

Women have increasingly become entitled to Social Security benefits based on their own work records, either as retired-worker beneficiaries only or as dually entitled beneficiaries. As shown in Figure 1, the percentage of women aged 62 or older entitled to benefits based on their own work records—as retired workers or as dually entitled beneficiaries—grew from 43% in 1960 to 79% in 2015. Most of this growth was in the percentage of dually entitled beneficiaries, however. The percentage of women aged 62 or older entitled to benefits based solely on their own work records fluctuated between 36% and 42% between 1960 and 2005, before increasing to 52% in 2015. In 2015, 48% of women aged 62 or older relied to some extent on benefits received as a spouse or survivor: 26% of spouse and survivor beneficiaries were dually entitled and 22% received spouse or survivor benefits only.

|

Figure 1. Basis of Entitlement for Women Aged 62 or Older, 1960-2015, |

|

|

Source: Social Security Administration, Annual Statistical Supplement, 2016, Table 5.A14, https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/statcomps/supplement/2016/5a.html#table5.a14. |

As shown in Table 2, among wives who are dually entitled spousal beneficiaries in December 2016, the retired-worker benefit accounted for 68% of the combined monthly benefit (the retired-worker benefit with a top-up provided by the spousal benefit) and the spousal benefit accounted for 32% of the combined monthly benefit, on average. Among widows who are dually entitled survivor beneficiaries, the retired-worker benefit and the widow(er)'s benefit each accounted for about half of the combined monthly benefit, on average.16

Many more women than men are dually entitled to retired-worker benefits and spousal or widow(er)'s benefits. As shown in the table, in December 2016, about 6.9 million women and 221,000 men were dually entitled to benefits.17

|

Average Monthly Benefit: |

||||

|

Type of Secondary Benefit |

Number |

Combined Benefit |

Retired-Worker Benefit |

Reduced Secondary Benefit |

|

All |

7,105,492 |

$1,221 |

$692 |

$530 |

|

Spouses |

3,126,904 |

$842 |

$572 |

$270 |

|

Wives of Retired and Disabled Workers |

3,050,314 |

$844 |

$573 |

$271 |

|

Husbands of Retired and Disabled Workers |

76,590 |

$777 |

$568 |

$209 |

|

Widow(er)s |

3,978,193 |

$1,520 |

$785 |

$734 |

|

Widows |

3,833,443 |

$1,522 |

$774 |

$747 |

|

Widowers |

144,750 |

$1,462 |

$1,076 |

$386 |

|

Parents |

395 |

$1,397 |

$636 |

$762 |

Source: Social Security Administration, Annual Statistical Supplement, 2017, Table 5.G3, https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/statcomps/supplement/2017/5g.html#table5.g3.

Note: Retired-worker benefit and reduced secondary benefit might not sum to the combined benefit due to rounding.

Women, Social Security, and Auxiliary Benefits

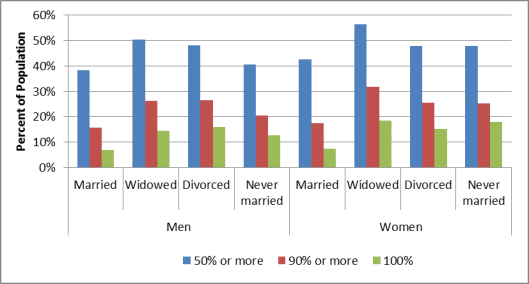

Spousal and survivor benefits play an important role in ensuring women's retirement security. In December 2016, about 24.0 million elderly (aged 65 and older) women receive Social Security benefits, including 12.1 million women who receive only retired-worker benefits, 2.1 million women who are entitled solely as the spouse of a retired worker, 3.3 million women who are entitled solely as the survivor of a deceased worker, and 6.6 million women who are dually entitled to a retired-worker benefit and a spousal or survivor benefit.18 In 2014, Social Security provided 50% or more of family income for more than 55% of elderly women in beneficiary families and 90% or more of family income for about 27% of elderly women in beneficiary families.19

Women, however, continue to be vulnerable to poverty in old age for several reasons. These reasons can generally be split into demographic reasons and economic reasons. In addition, the design of auxiliary benefits can lead to equity concerns.

With respect to demographic reasons that lead to adequacy concerns,

- Women on average live longer than men. Women reaching the age of 65 in 2016 are likely to live another 20.7 years, on average, compared with another 18.2 years for men.20 As a consequence, women spend more time in retirement and are more vulnerable to inflation and the risk of outliving other assets. The real value of pension benefits declines with age as pensions are generally not adjusted for inflation, and some pensions cease with the death of the retired worker.

- About 11% of women aged 50-59, and about 7% of women aged 60-75, have never married and therefore do not qualify for Social Security spousal or survivor benefits.21 Some argue that the unavailability of spousal and survivor benefits for women who have never been married, or who were married for less than 10 years, may be particularly problematic for minority and poor women.22

- About 5% of women aged 50-59, about 16% of women aged 60-75, and about 56% of women aged 75 and older are currently widowed. By comparison, about 2% of men aged 50-59, about 5% of men aged 60-75, and about 21% of men aged 75 and older are widowed.23

With regards to economic reasons,

- Women are more likely to take employment breaks to care for children or parents. During 2015, 88% of men and 74% of women aged 25-54 participated in the labor force.24 Breaks in employment result in fewer years of contributions to Social Security and employer-sponsored pension plans and thus lower retirement benefits.

- The median earnings of women who are full-time wage and salary workers are 81% of their male counterparts.25 Because Social Security and pension benefits are linked to earnings, this "earnings gap" can lead to lower benefit amounts for women than for men.

Social Security benefits are designed in a way that can result in inequities between households with similar earning profiles. Spousal and survivor benefits were added to the Social Security system in 1939. At that time, the majority of households consisted of a single earner—generally the husband—and a wife who was not in the paid workforce but instead stayed home to care for children. However, in recent decades, women have increasingly assumed roles as wage earners or as heads of families.

A beneficiary who qualifies for both a retired-worker benefit and a spousal benefit does not receive both benefits in full. Instead, the spousal benefit is reduced by the amount of the retired-worker benefit; this effectively means the beneficiary receives the higher of the two benefit amounts. Because of this, a two-earner household receives lower combined Social Security benefits than a single-earner household with identical total Social Security-covered earnings. Moreover, after the death of one spouse, the disparity in benefits may increase: in a one-earner couple, the surviving spouse receives two-thirds of what the couple received on a combined basis, whereas in some two-earner couples with roughly equal earnings, the surviving spouse receives roughly one-half of what the couple received on a combined basis.

Adequacy Issues

Social Security is a key component of total retirement income for both men and women. Figure 2 shows the extent to which men and women of different marital status rely on Social Security benefits. The height of the columns represents the average proportion of each subgroup that relies on Social Security for 50% or more, 90% or more, or 100% of their total retirement income.

|

Figure 2. Relative Importance of Social Security to Total Retirement Income for Persons Aged 65 or Older in 2014 |

|

|

Source: Social Security Administration, Income of the Population 55 or Older, 2014, April 2016, Table 8.B3, https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/statcomps/income_pop55/2014/sect08.html#table8.b3. |

Social Security is credited with keeping many of the nation's elderly out of poverty. However, in 2014, 7.3% of Social Security beneficiaries aged 65 or older were below the poverty line.26

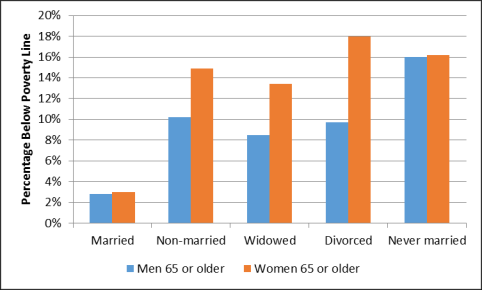

Error! Reference source not found.Figure 3 highlights the differences in poverty status among men and women aged 65 or older who receive Social Security benefits in 2014, after Social Security is combined with other sources of income such as earnings from work, pensions, income from assets, and cash assistance. In 2014, the poverty threshold for a single person aged 65 or older was $11,354 and for a married couple with a householder aged 65 or older (and no related children) was $14,309.27

|

Figure 3. Poverty Status of Social Security Beneficiaries Aged 65 or Older in 2014, by Gender and Marital Status |

|

|

Source: Social Security Administration, Income of the Population 55 or Older, 2014, April 2016, Table 11.3, https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/statcomps/income_pop55/2014/sect11.html#table11.3. Notes: Because the categories are by marital status, the "widowed" and "divorced" categories will include beneficiaries receiving widow(er) and divorced spouse benefits and beneficiaries receiving retired-worker benefits (based on his or her own work record). |

Figure 3Error! Reference source not found. shows that married beneficiaries have significantly lower poverty rates than nonmarried beneficiaries and that nonmarried women aged 65 or older—including widowed, divorced, and never-married women—are more likely to be in poverty than their male counterparts. Particularly vulnerable among women are divorced beneficiaries and the never-married. Among women aged 65 and older, about 18% of divorced Social Security beneficiaries and 16% of never-married Social Security beneficiaries have total incomes below the official poverty line. Research using data from the early 1990s found that beneficiaries receiving divorced spouse benefits have unusually high incidence of both serious health problems and poverty (in Figure 3Error! Reference source not found., the "divorced" category is the marital status, not the beneficiary status, and thus includes beneficiaries who receive divorced spouse benefits or retired-worker benefits).28 Among Social Security beneficiaries aged 65 and over, poverty rates are also high among never-married men and among minority women.29

The reasons for the disparity in poverty rates among elderly men and women relate in part to women's lower lifetime earnings, which affect Social Security benefits and pensions. Low lifetime earnings can be due to lower labor force participation of women and the earnings gap. In addition, women live two to three years longer than men on average, making them more likely to exhaust retirement savings and other assets before death. If the deceased husband was receiving a pension, the widow's benefit may be significantly reduced, or the pension may cease with the husband's death, depending on whether the couple had a joint and survivor annuity and how the joint and survivor annuity was structured. Elderly widows also may be at risk if assets are depleted by health-related expenses prior to the spouse's death.

Labor Force Participation of Women

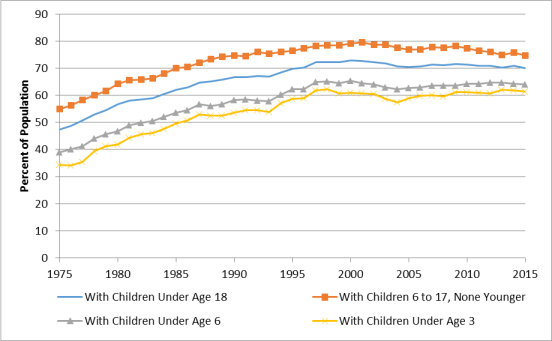

In 1950, about 34% of women aged 16 or older participated in the labor force, compared with about 86% of men aged 16 or older. By 2015, about 57% of women aged 16 or older participated in the labor force, compared with 69% of men in the same age group.30 Women with children under the age of 18 have increasingly entered the labor force in recent decades (Figure 4). However, women with children have fewer years of paid work, on average. By the age of 50, women without children who were born between 1948 and 1958 had worked on average about two years less than men overall (i.e., men with and without children). For a woman with two children, however, the gap at the age of 50 was about 6.5 years less than the average man with or without children. By the age of 50, African American women (with or without children) have worked, on average, about two years more than other women with or without children.31

|

Figure 4. Labor Force Participation Rates of Women with Children, 1975-2015 |

|

|

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Women in the Labor Force: A Databook, April 2017, Table 7, https://www.bls.gov/opub/reports/womens-databook/2016/home.htm. |

For many women, caregiving is also likely to lead to part-time work. Women are more likely than men to work part time (i.e., less than 35 hours per week in a sole or principal job). In 2015, 25% of women in wage and salary jobs worked part time, compared with 12% of men.32

In 2016, about 63% of mothers were employed. About two-thirds of mothers who worked in 2016 were in a dual-earner family. The remaining third were the sole job-holders in their family, because their spouses were either not employed or not present.33

Women with more education and women in later birth cohorts are likely to have longer employment histories than other women.34 In 2015, women accounted for more than half of all workers within several industry sectors: financial activities (women constituted 53% of employees in this sector), education and health services (75%), leisure and hospitality (51%), private households (93%), and other services (52%). However, women were under-represented (relative to their share of total employment) in agriculture (25%), mining (13%), construction (9%), manufacturing (29%), and transportation and utilities (23%).35

Earnings Gap

Another reason why women receive lower retired-worker benefits than men is that full-time women workers earn about 80%-81% of the median weekly earnings of their male counterparts.36 In 2015, women who were full-time wage and salary workers had median weekly earnings of $726, or about 81% of the $895 median earned by their male counterparts. The women's-to-men's earnings ratio was about 62% in 1979 and, after increasing gradually during the 1980s and 1990s, has ranged between 80% and 81% since 2004.37

In 2015, the earnings gap between women and men varied among age groups (see Table 3). Among full-time workers, women aged 16-24 earned 88% as much as men (down from a high of 95% in 2010); women aged 25-34 earned about 90% as much as men; and women aged 55-64 earned about 74% as much as men.

Over time, the earnings gap between women and men has narrowed for most age groups. For example, among full-time workers aged 25-34, the women's-to-men's earnings ratio increased from 68% in 1979 to 90% in 2015. For workers aged 35-44, the earnings ratio increased from 58% in 1979 to 82% in 2015. Similarly, for workers aged 45-54, the earnings ratio increased from 57% in 1979 to 77% in 2015.

Comparing the annual earnings of women and men may understate differences in total earnings across longer periods. Using a 15-year time frame (1983-1998), one study found that women in the prime working years of 26 to 59 had total earnings that were 38% of what prime-age men earned, in total, over the same 15-year period.38 Another study found that women born between 1955 and 1959 who worked full-time, year-round each year would have an average lifetime loss of $531,500 by age 59, compared with men.39

|

Age |

Women's Earnings as a Percentage of Men's, 1979 |

Women's Earnings as a Percentage of Men's, 2015 |

||||

|

Total, 16 years and older |

|

|

||||

|

Total, 16 to 24 years |

|

|

||||

|

Total, 25 years and older |

|

|

||||

|

25 to 34 years |

|

|

||||

|

35 to 44 years |

|

|

||||

|

45 to 54 years |

|

|

||||

|

55 to 64 years |

|

|

||||

|

65 years and older |

|

|

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Highlights of Women's Earnings in 2015, November 2016, Table 12, https://www.bls.gov/opub/reports/womens-earnings/2015/home.htm.

Note: Ratios are for men and women who are full-time wage and salary earners with median earnings.

As women enter the work force in greater numbers, more women will qualify for Social Security benefits based on their own work records, instead of a spousal benefit that is equal to 50% of the husband's PIA. However, retired-worker and disabled-worker benefits for women continue to be lower than those for men on average for a variety of reasons, as discussed above. Consequently, after the death of a husband, the survivor's benefit, which is equal to 100% of the husband's PIA, will continue to play an important role in the financial well-being of widows.

Equity Issues

Although Social Security provides essential income support to nonworking spouses and widows, the current-law spousal benefit structure can lead to a variety of incongruous benefit patterns that have been documented in the literature.40 For example, a woman who was never employed but is married to a man with high Social Security-covered wages may receive a Social Security spousal benefit that is higher than the retirement benefit received by a single woman, or a woman who was married less than 10 years, who worked a full career in a low-wage job.

The current system also provides proportionately more benefits relative to payroll-tax contributions to one-earner couples (which predominated when Social Security was created in the 1930s) than to single persons or to couples with two-earners, on average. As a result, the current system can lead to situations in which Social Security provides unequal benefits to one-earner and two-earner couples with the same total household lifetime earnings. Putting this in a different perspective, some two-earner couples may have to contribute significantly more to Social Security to receive the same retirement and spousal benefits that the system provides to a one-earner couple with identical total household earnings. As women's share of household income has increased, and also as women have increasingly become heads of families, these anomalies could become more relevant.

Table 4 illustrates the disparate treatment of one-earner and two-earner couples with examples developed by the American Academy of Actuaries. In the table, a one-earner couple with household earnings of $50,000 is compared with two different two-earner couples. The second couple in the comparison is a two-earner couple with the same total household earnings ($50,000) as the one-earner couple, with the earnings evenly split between the two spouses (each spouse earns $25,000). The third couple in the comparison is a two-earner couple in which one spouse earns $50,000 (the same as the primary earner in the one-earner couple) and the other spouse earns half that amount, or $25,000, for total household earnings of $75,000.

|

First Couple: One Earner with Earnings of $50,000 |

Second Couple: Two Earners with Total Household Earnings of $50,000 Split Evenly |

Third Couple: Two Earners with Earnings of $50,000 and $25,000 |

|

|

Total household earnings |

$50,000 |

$50,000 |

$75,000 |

|

Spouse A earns |

$50,000 |

$25,000 |

$50,000 |

|

Spouse B earns |

$0 |

$25,000 |

$25,000 |

|

Annual Social Security payroll taxes (employee share only) |

$3,100 |

$3,100 |

$4,650 |

|

Total monthly benefit paid to couple at retirement |

$2,655 total (equals $1,770 worker benefit to Spouse A and $885 spousal benefit to Spouse B) |

$2,240 total (equals $1,120 worker benefit to Spouse A and $1,120 worker benefit to Spouse B) |

$2,890 total (equals $1,770 worker benefit to Spouse A and $1,120 worker benefit to Spouse B) |

|

Total monthly benefit paid to survivor |

$1,770 |

$1,120 |

$1,770 |

Source: American Academy of Actuaries, Women and Social Security, Issue Brief, May 2017.

As the table illustrates, a one-earner couple may receive higher retirement and survivor benefits than a two-earner couple with identical total household earnings. Specifically, the first couple with one earner receives a total of $2,655 in monthly retirement benefits, compared with the second couple with two earners who receives a total of $2,240 in monthly retirement benefits. Similarly, the survivor of the one-earner couple receives $1,770 in monthly benefits (either as a retired worker or as a surviving spouse). In comparison, the survivor of the two-earner couple with identical total household earnings receives $1,120 in monthly benefits.

The third couple shown in Table 4, both spouses work in Social Security-covered employment, but in this example one spouse earns $50,000 annually and the other spouse earns $25,000. This couple receives monthly benefits that are $235 higher than the monthly benefits received by the one-earner couple ($2,890 compared with $2,655); however, this couple has earned much more over time ($25,000 annually) and contributed commensurately more in Social Security payroll taxes ($1,550 annually). The survivor benefit received by the third couple is identical to that received by the one-earner couple. Thus, the current-law Social Security spousal benefit structure requires some two-earner couples to make substantially higher contributions for similar benefit levels. With higher earnings but similar benefits to the one-earner couple, the third couple's replacement rate (i.e., initial monthly benefits as a percentage of preretirement earnings) is lower than that of the one-earner couple.41

After the death of one spouse, the disparity in benefits between one-earner and two-earner couples may increase, as shown in the table. For the one-earner couple, the surviving spouse receives a benefit equal to two-thirds of the couple's combined benefit (for a reduction equal to one-third of the couple's combined benefit).42 For a two-earner couple with equal earnings (the second couple), the surviving spouse receives a benefit equal to one-half of the couple's combined benefit.

Further, the surviving spouse in the first couple (the one-earner couple) receives a larger monthly benefit than the survivor of the second couple (a two-earner couple with earnings evenly split)—$1,770 compared with $1,120—although both couples paid the same amount of Social Security payroll tax contributions. Similarly, compared with the one-earner couple, the surviving spouse in the third couple (a two-earner couple with unequal earnings and higher total earnings than the one-earner couple) receives the same monthly benefit ($1,770) although the couple paid a higher amount of Social Security payroll tax contributions. For both two-earner couples in these examples, after the death of one spouse, the second earnings record does not result in the payment of any additional benefits.43

In addition to inequities among couples with different work histories and earnings levels, the current structure of Social Security auxiliary benefits creates inequities among the divorced. Divorced spouses with 9½ years of marriage, for example, receive no Social Security spousal and survivor benefits, whereas divorced spouses with 10 or more years of marriage may receive full spousal and survivor benefits.

Other Program Design Considerations

The current structure of Social Security spousal and survivor benefits also raises other considerations.

- Divorced spouses receive a higher benefit after the death of their former spouse (the primary earner): benefits for a divorced spouse are equal to 50% of the primary earner's PIA, while benefits for a divorced surviving spouse are equal to 100% of the primary earner's PIA. This can create volatility in the income of divorced spouses.

- Social Security automatically provides pension rights to one or more eligible divorced spouses, in contrast to private pensions. Further, the benefit payable to the primary earner is not reduced for benefits paid to a current or one or more former spouses, again in contrast to private pensions.

- Widow(er)s who had high-earning spouses may face disincentives to marry a lower-earning second husband (if remarriage occurs before the eligibility age for widow[er]'s benefits).

- For most married women who will depend on the spousal benefit, lifetime Social Security benefits are maximized by claiming benefits as early as possible, unless the benefit based on the wife's work record is less than 40% of her husband's, in which case the age differential between the two spouses becomes important in determining the wife's optimum claiming age.44

In response to the adequacy, equity, and other program design issues described above, policymakers and researchers have proposed a number of ways to restructure Social Security auxiliary benefits. Some of these proposals are discussed in the following section.

Proposals for Restructuring Social Security Auxiliary Benefits

A number of proposals have been put forward to modify the current structure of Social Security spousal and survivor benefits. These proposals have different potential consequences for benefit levels for current, former and surviving spouses, for the redistribution of benefits among couples from different socio-economic levels, for eligibility for means-tested programs such as Supplemental Security Income, and for work incentives. Proposals can affect claiming strategies for those attempting to "game the system" into receiving the maximum benefits possible, though this possibility has been minimized due to the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015.45

Earnings Sharing

Earnings sharing has been suggested as a way to address the unequal treatment of one-earner versus two-earner couples under current law. As noted above, Social Security often provides higher benefits to one-earner couples than to two-earner couples with the same total household earnings. In addition, earnings sharing has sometimes been suggested as a way to provide benefits to divorced women whose marriages did not last long enough (at least 10 years) to qualify them for divorced spouse or survivor benefits. By definition, earnings sharing would not affect never-married persons.

Under the most basic form of earnings sharing, spousal and survivor benefits would be eliminated. Instead, for each year of marriage, a couple's covered earnings would be added together and divided evenly between the spouses. For years when an individual is not married, his or her own earnings would be recorded. If a person has multiple marriages, the earnings sharing would occur during each period of marriage. Both members of a couple would have individual earnings records reflecting shared earnings as a member of the couple as well as any earnings before or after the marriage. Social Security benefits would be computed separately for each member of the couple, based on the individual earnings records and using the current-law benefit formula. For couples who were married for the entire career of one or both members, both members of the couple would receive identical benefits and the couple's combined benefit would be equal to twice that of either member of the couple. The two spouses would receive different benefits, however, if either had earnings before or after the marriage.

Earnings sharing proposals would reduce benefits for the majority of individuals, relative to current law, and in the absence of other benefit enhancements. For example, a 2009 Social Security Administration (SSA) study (hereinafter, 2009 SSA Study)46 found that 61% of individuals would receive average benefit reductions of about 17%. About 11% of individuals would experience no change in benefits, and 28% would experience benefit increases averaging about 10%.

A report issued by the House Committee on Ways and Means in 1985 examined the impact of a generic earnings sharing plan, as described above, on one-earner and two-earner couples in 2030. In the absence of transition provisions, about 64% of men and about 37% of women would have lower benefits than under current law. Average benefits for aged beneficiaries would decline by about 4.5%.47

Studies have found that the largest benefit reductions under earnings sharing could affect widows and divorced widows. The 2009 SSA study found that about 93% of widows would experience an average benefit reduction of 27% while 45% of divorced women would experience benefit reductions averaging about 22%.48 The 1985 congressional study found that 67% of widows would experience lower benefits with the benefit loss averaging 29%, while 39% of divorced women would experience lower benefits with the benefit loss among this group averaging 31%. A 2017 study found that 39% of divorced women and 62% of widows would experience a median decrease in benefits of 6% and 14%, respectively.49

The decline in widow's benefits results from eliminating the surviving spouse benefit under current law and replacing it with earnings credits. The widow's benefit under current law is equal to 100% of the husband's PIA, where the husband's PIA is determined based on unshared earnings. Although earnings sharing would increase the amount of earnings credited to the surviving wife (assuming the husband was the higher earner), the benefit payable to the surviving wife based on shared earnings would be lower than the current-law widow's benefit. Another study found that the gains experienced by divorced spouses and some married women under earnings sharing would come largely at the expense of widowed men and women.50

Some earnings sharing proposals would mitigate these effects by providing enhanced benefits to survivors or other targeted groups. For example, an "inheritance provision" could allow a surviving spouse to count all (instead of half) of a deceased spouse's earnings (or those of a deceased former spouse) during each year of marriage, in addition to all of his or her own earnings. An inheritance provision would protect some, though not all, surviving spouses. For example, the 2009 SSA study found that 40% of widows would receive lower benefits relative to current law under earnings sharing with an inheritance provision.

Alternatively, benefits for surviving spouses could be based on an amount equal to two-thirds of the combined benefit the couple was receiving when both members of the couple were alive (see "Survivor's Benefit Increased to 75% of Couple's Combined Benefit" below), or special provisions could be targeted to surviving disabled spouses.51

Provisions to protect survivors from benefit reductions, however, would reduce the amount of savings that would otherwise be achieved through program changes. Similarly, provisions to increase benefits for survivors relative to current law would increase program costs. A higher survivor benefit could be self-financed by reducing, on an actuarially fair basis, the combined benefit the couple receives while both members of the couple are alive.52

Divorced Spouse Benefits

Under the Social Security program, a divorced spouse must have been married to the worker for at least 10 years to qualify for spousal and survivor benefits based on the worker's record, as discussed above. Benefits for divorced spouses are equal to 50% of the worker's PIA; benefits for divorced surviving spouses are equal to 100% of the worker's PIA. One approach to extend Social Security spousal and survivor benefits to more divorced spouses would be to lower the 10-year marriage requirement (for example, to 5 or 7 years). Proposals to lower the length-of-marriage requirement for divorced spouses would improve benefit adequacy for some, although not all, divorced women.

One study estimated that lowering the marriage-duration requirement from 10 to 7 years would increase benefits for about 8% divorced women and 2% of widowed women aged 60 or older in the year 2030. Lowering the marriage-duration requirement to 5 years (with a proportional decrease to benefit amounts) would increase benefits for about 11% of all divorced women in the year 2030. The study found that, among divorced women aged 60 and over who would receive higher benefits as a result of lowering the marriage-duration requirement to 5 or 7 years, the outcomes were moderately progressive in the sense that they channeled a greater share of benefit increases to low-income and non-college-educated divorced women in old age. For example, under a 7-year marriage-duration requirement, about 10% of divorced women in the lowest retirement income quintile would receive a benefit increase compared with around 4% in the highest quintile who would receive a benefit increase. Among divorced women who gain, women in the lowest retirement income quintile would see a median benefit increase of 79%, compared with a median increase of 25% among women in the highest quintile.53 An earlier study found a similar result.54

Some researchers contend that the 50% benefit rate for divorced spouses (50% of the worker's PIA) is not sufficient to prevent many divorced spouses from falling into poverty.55 The 50% benefit rate for spouses initially was established to supplement the benefit received by a one-earner couple (i.e., in 1939, a spousal benefit was provided for a dependent wife to supplement the benefit received by the worker).56 Some observers contend that it may not be sufficient for persons (divorced spouses) who may be living alone. As described above, about 16.5% of divorced women and 8.7% of divorced men have incomes below the poverty line, compared to 2.3% of married men and women (see Error! Reference source not found. Figure 3 above). It has been estimated that increasing the benefit rate for divorced spouses from 50% to 75% of the worker's PIA would lower the poverty rate among divorced spouses from 30% to 11%.57

Increased Benefits for the Oldest Old

Another type of benefit modification would increase benefits for the oldest old (for example, beneficiaries aged 80 or older, or after 20 years of benefit receipt) by a specified percentage such as 5% or 10%. One rationale for this proposal is that beneficiaries tend to exhaust their personal savings and other assets over time, becoming more reliant on Social Security at advanced ages. Another rationale is that, after the age of 60, Social Security retirement benefits do not keep pace with rising living standards. In particular, the formula for computing a worker's initial retirement benefit is indexed to national average wage growth through the age of 60 and then to price inflation (the Consumer Price Index for Urban Wage and Clerical Workers, or CPI-W) starting at the age of 62. Once a beneficiary begins receiving benefits, his or her benefits increase each year with price inflation (the annual cost-of-living adjustment, based on the CPI-W) so that the initial benefit amount is effectively fixed in real terms. Some argue that the CPI-W is an inaccurate measure of price inflation that seniors face.58

In 2010, the National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform and the Bipartisan Policy Center both proposed packages that combined, among other measures, a benefit "bump up" after 20 years of benefit receipt, a change in the benefit formula, and a move to basing the Social Security COLA on the chained CPI-U instead of on the CPI-W (the chained CPI-U tends to grow more slowly than the CPI-W).59

According to one study, a 5% bump-up in benefits at the age of 80 would result in a slight decline in poverty rates among widows and nonmarried retired-worker beneficiaries aged 80 or older (declines of 3 percentage points and 4 percentage points, respectively). The same study found that this option is not targeted toward low-income beneficiaries: less than 30% of the additional benefits would accrue to beneficiaries in the bottom quintile of the income distribution.60

Alternatively, a benefit increase for the oldest old could be limited to beneficiaries who receive a below-poverty-level benefit. One proposal along these lines would provide a benefit to persons aged 82 or older that would be pro-rated based on the number of years the person contributed to Social Security.61

Minimum Benefit for Low Earners

Some observers argue that a carefully designed minimum benefit has the potential to reduce poverty rates among older women, including divorced and never-married women, more efficiently than existing spousal and survivor benefits.62 Minimum benefit proposals are aimed at improving the adequacy of benefits, in comparison with some other proposals that address issues of equity among individuals and couples with different marital statuses.

Most minimum benefit proposals would require the worker to have between 20 and 30 years of Social Security-covered earnings to qualify for a minimum benefit at the poverty line or somewhat above it (for example, 120% of the poverty line).63 These work tenure requirements are intended to address, although not resolve, concerns that providing a minimum benefit could discourage work effort. Setting eligibility for a minimum benefit at 20 to 30 years of covered earnings would allow many workers to take several years out of the labor force to care for children (or other family members) and still receive a higher benefit than they would have qualified for in the absence of a minimum benefit. Arguably, intermittent work histories play a greater role than long-term low earnings in leading to below-poverty-level benefits among women.64 Therefore, proposals for a minimum benefit based on a specified number of years of covered employment could be combined with modified spousal benefits or with a caregiver credit to balance recognition of longer work effort with recognition of the requirements of caregiving.65

Some women, however, do not reach 20 years of covered earnings. About 40% of women aged 60 to 64 in 2000 had fewer than 20 years of earnings.66 This percentage is likely to decline in younger cohorts. Moreover, minimum benefit provisions may have the unintended effect of providing minimum benefits to workers with high earnings but sporadic work histories.

To maintain the minimum benefit at a constant ratio to average living standards, some proposals would link the minimum benefit to wage growth instead of setting the minimum benefit equal to a specified percentage of the poverty line.67 The official poverty line is indexed to price growth, whereas living standards rise with increases in wages and productivity. Wage growth generally outpaces price growth.68

Social Security already has a "special minimum" benefit designed to help workers with long careers at low wages.69 The number of beneficiaries who receive the special minimum benefit under current law declines each year, however, and the Social Security Administration estimates that it is likely to cease raising benefits for new retirees in the near future.70 A worker is awarded the special minimum benefit only if it exceeds the worker's regular benefit. The value of the special minimum benefit, which is indexed to prices, is rising more slowly than the value of the regular Social Security benefit, which is indexed to wages.

The 2010 National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform and the Bipartisan Policy Center both proposed packages that included, among other measures, provisions to create new minimum benefits.71 Some researchers propose modernizing the special minimum benefit by tying it to a poverty level that is in line with the recommendations of the National Academy of Social Insurance.72 If a new minimum benefit is provided, it would be necessary to address interactions between Social Security benefits and eligibility for Supplemental Security Income, Medicaid, and other means-tested programs for low-income individuals.

Caregiver Credits and Drop-out Years for Caregiving

Women are more likely than men to take career breaks to care for a child or other relative, as discussed above. The Social Security retired-worker benefit is based on the average of a worker's 35 highest years of covered earnings. If a worker has fewer than 35 years of earnings, for example due to years of unpaid caregiving, years of no earnings are entered as zeros in the computation of career-average earnings. Years of zero earnings lower the worker's career-average earnings, resulting in a lower initial monthly benefit.

One approach is to replace years of low or zero earnings with a caregiver credit equal to a specified dollar amount. Some proposals would provide the same fixed credit to all eligible persons.73 Other proposals would link the amount of the credit to foregone earnings, so that higher earners would receive higher credits. The latter proposal would require that the caregiver have been in the paid labor force previously. Some proposals to base benefits on caregiving, rather than on marriage, would eliminate the current spousal benefit.

A second approach is to drop years of caregiving, up to a fixed maximum number of years, from the benefit computation period. This approach could be implemented either by dropping years of zero earnings or by dropping years of low earnings.74 The proposal to drop years of zero earnings (rather than low earnings) would require a person to leave the workforce completely. This could be problematic for many women, making the proposal less likely to reach as many women as a caregiver credit. Allowing a parent to drop up to five years of zero (or low) earnings for caring for a child at home would cause the parent's AIME to be calculated based on the highest 30 years of earnings, rather than the highest 35 years of earnings (the benefit computation periods would be reduced from 35 years to 30 years). This change in the benefit computation would result in higher initial monthly benefits for these workers (and higher benefits for family members who receive benefits based on their work records).

The Social Security Disability Insurance program allows up to three "drop-out" years for caregiving.75 Policies to credit years of caregiving in the provision of public pension benefits have been implemented in other countries in a variety of ways. In making such a provision, one question to consider is whether the credit should be available only to parents who have stopped working completely or also to parents who continue to work part-time or full-time. Another question to consider is whether to provide credits only for the care of young children or also for the care of other immediate family members such as an aging parent. For example, Canada excludes years of caring for children under the age of 7 from the averaging period in the pension calculation and from the contributory period under its earnings-related scheme, while Germany provides one pension point (equal to a year's contributions at the national average earnings) for three years per child, which can be taken by either the employed or nonemployed parent, or shared between parents (there are also credits for working while children are under the age of 10).76

Other recent proposals, however, would count additional years of earnings (more than 35 years) in the Social Security benefit computation. For example, some proposals would increase the averaging period from 35 to 38 years.77 These proposals are aimed at helping improve Social Security's projected long-range financial position and at encouraging people to work longer. Such proposals generally would affect women disproportionately.

A criticism of proposals to drop or credit years of caregiving is that they may be of most benefit to higher-wage households that can afford to forego one spouse's earnings over a period of several years. Lower-wage spouses, and single working mothers, may not be in a position to stop working for any period of time. In addition, a practical issue involves ascertaining that years out of the workforce are actually spent caring for children or other family members.

Survivor's Benefit Increased to 75% of Couple's Combined Benefit

Under current law, an aged surviving spouse receives the higher of his or her own retired-worker benefit and 100% of the deceased spouse's PIA. This leads to a reduction in benefits compared with the combined benefit the couple was receiving when both members of the couple were alive. The reduction ranges from one-third of the combined benefit for a one-earner couple to one-half of the combined benefit for some two-earner couples.78 However, there is not always a corresponding reduction in household expenses for the surviving member of the couple. Some contend that 75% of the income previously shared by the couple more closely approximates the income needed by the surviving spouse to maintain his or her standard of living.79

One frequently mentioned proposal would increase the surviving spouse's benefit to the higher of (1) the deceased spouse's benefit, (2) the surviving spouse's own benefit, and (3) 75% of the couple's combined monthly benefit when both spouses were alive.80 The couple's combined monthly benefit when both spouses were alive would be the sum of (1) the higher-earner's benefit and (2) the higher of the lower-earner's worker benefit and spousal benefit. Some proposals for a 75% survivor benefit would target the provision to lower-income households by capping the survivor benefit, for example, at the benefit amount received by the average retired-worker beneficiary.81

A 75% minimum survivor benefit would increase benefits for many surviving spouses, both in dollar terms and as a replacement rate for the combined benefit received by the couple when both spouses were alive. For a one-earner couple, the benefit for the surviving spouse would increase from 100% to 112% of the worker's benefit (112% = 75% of 150% of the worker's benefit that the couple received when both spouses were alive). For a two-earner couple with similar earnings histories, the surviving spouse's benefit would increase from roughly 50% of the couple's combined benefit when both spouses were alive (under current law, the surviving spouse receives the benefit received by the higher-earning spouse while he or she was alive) to 75% of the couple's combined benefit when both spouses were alive.

A 75% minimum survivor benefit provision would "reward" the second income of a two-earner couple and improve equity between one-earner and two-earner couples. Under current law, upon the death of either spouse, the earnings record of the lower-earning spouse does not result in the payment of any additional benefits (i.e., in addition to the benefits payable on the earnings record of the higher-earning spouse). Stated another way, the earnings record of the lower-earning spouse effectively "disappears" with the death of either spouse.

Because a 75% survivor benefit would increase costs to the Social Security system, some have proposed financing it through a gradual reduction in the spousal benefit from 50% to 33% of the primary earner's benefit, while both spouses are alive.82 For a one-earner couple, the couple's combined benefit would be reduced from 150% to 133% of the worker's benefit. This is broadly consistent with the structure of private annuities, where the annuity payout is lower to adjust for a longer expected payout period. As a result, more dually entitled spouses would likely qualify for a retirement benefit based on their own work record only, because more dually entitled spouses would likely have a retired-worker benefit of their own that is equal to at least 33% (rather than 50%) of the higher-earning spouse's retired-worker benefit.

Reducing a one-earner couple's combined monthly benefit to 133% of the worker's benefit, as a way to finance a 75% survivor benefit, could be problematic for low-income couples. Effectively, the increased survivor benefit would help the survivors of both one-earner and two-earner couples, but it would be financed by reducing the combined benefits of one-earner couples from 150% to 133% of the worker's benefit. In addition, unless this proposal were modified for divorced spouses, it would also reduce the spousal benefits received by divorced spouses from 50% to 33% of the primary earner's benefit. After the death of the primary earner, benefits for a divorced spouse would jump to 100% of the primary earner's benefit, creating income volatility unless this outcome is addressed for divorced spouses.

Although the 75% survivor benefit option could increase benefits for vulnerable groups such as aged widows, it would not address the needs of other vulnerable groups, such as individuals who were never married or who divorced before reaching 10 years of marriage. In addition, a 75% survivor benefit option would provide somewhat more additional benefits to higher-income beneficiaries than to lower-income beneficiaries. To address this outcome, as noted above, some proposals would cap the 75% survivor benefit at the average retired-worker benefit.

Conclusion

This report described the current-law structure of Social Security auxiliary benefits for spouses, former spouses, and surviving spouses. When Social Security auxiliary benefits were established in 1939, they were based on the typical family structure at the time consisting of a single wage-earner—generally the husband—and a wife who stayed at home to care for children and remained out of the paid workforce. As a result, a woman who was never employed but is married to a man with high Social Security-covered wages may receive a Social Security spousal benefit that is larger than the retirement benefit received by a single woman, or a woman who was married less than 10 years, who worked a full career in a low-wage job. In recent decades, this family structure has changed: women have entered the workforce in increasing numbers, more men and women remain single, and divorce rates have risen. As a result, more women now qualify for Social Security retirement benefits based on their own work records.

Social Security auxiliary benefits, however, continue to play a crucial role in improving income security for older women, as well as for young surviving spouses and children of deceased workers. Women in particular continue to be vulnerable to poverty in old age and depend on the income support provided by Social Security.

Some policymakers and researchers have expressed concerns about the current structure of Social Security auxiliary benefits on both equity and adequacy grounds. The current structure can lead to situations in which a one-earner couple receives higher retirement and survivor benefits than a two-earner couple with identical total household earnings. In addition, auxiliary benefits do not reach certain groups, such as persons who divorced before 10 years of marriage or mothers who never married.

This report presented a number of recent proposals for modifying the current structure of Social Security spousal and survivor benefits. Each of the proposals generally targets benefit increases to certain, but not all, vulnerable groups. For example, an enhanced widow(er)'s benefit would provide income support to many elderly women and men, but it would not help those who divorced before 10 years of marriage or who never married. Similarly, a caregiver credit for workers who stay at home to care for young children would increase benefits for never-married and divorced women, but it would not help those without children, whether married or unmarried.

The consideration of potential changes to Social Security spousal and survivor benefits involves balancing improvements in benefit equity, for example, between one-earner and two-earner couples, with improvements in benefit adequacy for persons who experience relatively higher poverty rates, such as never-married men and women. In addition, the policy discussion about auxiliary benefits may involve balancing benefit increases for spouses and survivors, divorced spouses, or never-married persons with other potential program changes to offset the higher program costs in light of the Social Security system's projected long-range financial outlook.83

Appendix A. Major Changes in Social Security Auxiliary Benefits

|

Amendment |

Type of Benefit |

Amendment |

Type of Benefit |

|||

|

Retired Workers |

Dependents of Disabled Workers |

|||||

|

|

Retired worker aged 65 and older |

|

Same as dependents of retired-worker recipient |

|||

|

|

Retired woman aged 62-64 |

|

||||

|

|

Retired man aged 62-64 |

|

Widowed Mother |

|||

|

|

|

Widowed mother any age caring for eligible child |

||||

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

Disabled worker aged 50-64 |

|

Widow |

|||

|

|

Disabled worker under age 65 |

|

Widow aged 65 and older |

|||

|

|

|

Widow aged 62-64 |

||||

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

Wife |

|

Divorced widow aged 60 and older |

|||

|

|

Wife aged 65 and older |

|

Disabled widow aged 50-59 |

|||

|

|

Wife under age 65 caring for eligible child |

|

||||

|

|

Wife aged 62-64 |

|

Widower |

|||

|

|

|

Dependent widower aged 65 and older |

||||

|

|

Child |

|

Dependent widower aged 62-64 |

|||

|

|

Child under 18 |

|

Disabled dependent widower aged 50-61 |

|||

|

|

Disabled child aged 18 and older |

|

Widower aged 60-61 |

|||

|

|

Full-time student aged 18-21 |

|

||||

|

|

Student category eliminated except for high school |

|

Widowed Father |

|||

|

|

students under age 19 |

|

Widowed father caring for eligible child |

|||

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

Husband |

|

Child |

|||

|

|

Husband aged 65 and older |

|

Child under age 18 |

|||

|

|

Husband aged 62-64 |

|

Disabled child aged 18 and older |

|||

|

|

Husband under age 65 caring for eligible child |

|

Full-time student aged 18-21 |

|||

|

|

|

Student category eliminated except for high school |

||||

|

|

Divorced Wife |

|

students under age 19 |

|||

|

|

Divorced wife age 62 and older |

|

||||

|

|

|

Parent |

||||

|

|

Divorced Husband |

|

Dependent parent aged 65 and older |

|||

|

|

Divorced husband aged 62 and older |

|

Dependent female parent aged 62-64 |

|||

|

|

Dependent male parent aged 62-64 |

|||||

Appendix B. Computation of the Social Security Retired-Worker Benefit

To be eligible for a Social Security retired-worker benefit, a person generally needs 40 quarters of coverage (among other requirements).84 A worker's initial monthly benefit is based on his or her 35 highest years of earnings, which are indexed to historical wage growth to bring past earnings in line with current wage levels (earnings through the age of 60 are indexed; earnings thereafter are counted at nominal value). The 35 highest years of indexed earnings are divided by 35 to determine the worker's career-average annual earnings. The resulting amount is divided by 12 to determine the worker's average indexed monthly earnings (AIME). If a worker has fewer than 35 years of earnings in covered employment (because of time out of the labor force for family caregiving, spells of unemployment or other reasons), years of no earnings are entered as zeros.

The worker's basic benefit amount (i.e., basic benefit before any adjustments for early or delayed retirement) is called the primary insurance amount (PIA). The PIA is determined by applying a formula to the AIME as shown in Table B-1. First, the AIME is sectioned into three brackets (or levels) of earnings. Three progressive replacement factors—90%, 32%, and 15%—are applied to the three different brackets of AIME. The three products derived from multiplying each replacement factor and bracket of AIME are added together to get the worker's PIA. Because the replacement factors are progressive, the benefit formula replaces a higher percentage of the preretirement earnings of workers with low career-average earnings than for workers with high career-average earnings. For workers who become eligible for retirement benefits, become disabled, or die in 2017, the PIA is determined as shown in the example in Table B-1.

Table B-1. Computation of a Worker's Primary Insurance Amount (PIA) in 2017 Based on an Illustrative AIME of $6,000

|

Factors |

Three Brackets of AIME |

PIA for Worker with an Illustrative AIME of $6,000 |

||

|

90% |

first $885 of AIME, plus |

|

||

|

32% |

AIME over $885 and through $5,336 plus |

|

||

|

15% |

AIME over $5,336 |

|

||

|

Total Worker's PIA (rounded down to nearest 10 cents) |

$2320.40 |

|||

Source: Congressional Research Service.

Adjustment to Benefits Claimed Before or After FRA

A worker's initial monthly benefit is equal to his or her PIA if he or she begins receiving benefits at full retirement age (FRA).85 A worker's initial monthly benefit will be less than his or her PIA if he or she begins receiving benefits before FRA, and it will be greater than his or her PIA if he or she begins receiving benefits after FRA. Workers can claim as early as the earliest eligibility age (EEA), which is 62.

Retirement benefits are reduced by five-ninths of 1% (or 0.0056) of the worker's PIA for each month of entitlement before FRA up to 36 months, for a reduction of about 6.7% a year. For each month of entitlement before FRA in excess of 36 months (up to 24 months), retirement benefits are reduced by five-twelfths of 1% (or 0.0042) of the worker's PIA, for a reduction of 5% a year.

Workers who delay filing for benefits until after FRA receive a delayed retirement credit (DRC). The DRC applies beginning with the month the worker attains FRA and ending with the month before he or she attains the age of 70. Starting in 1990, the DRC was increased until it reached 8% per year for workers born in 1943 or later.

The actuarial adjustment to benefits claimed before or after FRA is intended to provide the worker with roughly the same total lifetime benefits regardless of the age at which he or she begins receiving benefits (assuming he or she lives to average life expectancy). Therefore, if a worker claims benefits before FRA, his or her monthly benefit is reduced to take into account the longer expected period of benefit receipt. Similarly, if a worker claims benefits after FRA, his or her monthly benefit is increased to take into account the shorter expected period of benefit receipt.

Other benefit adjustments may apply, such as those related to simultaneous entitlement to more than one type of Social Security benefit (for more information see the section above entitled "Dually Entitled Beneficiaries"). Under the windfall elimination provision (WEP), the Social Security benefit formula is modified to reduce benefits for persons who have pensions from noncovered employment.86 The Social Security maximum family benefit provision may cap total benefits received by members of a family, by reducing the benefits of individual family members.87 Under the retirement earnings test (RET), the monthly Social Security benefit is reduced for persons who are below FRA and have wage or salary incomes above an annual dollar threshold (annual exempt amount).88

Appendix C. Summary of Social Security Spousal and Widow(er)'s Benefits Under Current Law

Social Security benefits for spouses and widow(er)s are based on a percentage of the worker's primary insurance amount (PIA), with various adjustments for age at entitlement and other factors. The following section describes some of the adjustments that apply to benefits for spouses and widow(er)s.

Age-Related Benefit Adjustment for Spouses

Spousal benefits (including those for divorced spouses) are reduced when the spouse claims benefits before full retirement age (FRA) to take into account the longer expected period of benefit receipt (assuming the individual lives to average life expectancy).89 A spouse who claims benefits at the age of 62 (the earliest eligibility age for retirement benefits) may receive a benefit that is as little as 32.5% of the worker's PIA.90

Age-Related Benefit Adjustments for Widow(er)s

The earliest age a widow(er) can claim benefits is age 60. If a widow or widower (including divorced and disabled widow(er)s) claims survivor benefits before FRA,91 his or her monthly benefit is reduced by a maximum of 28.5%92 to take into account the longer expected period of benefit receipt (assuming he or she lives to average life expectancy).

In addition, survivor benefits may be affected by the deceased worker's decision to claim benefits before FRA. If the deceased worker claimed benefits before FRA (and therefore was receiving a reduced benefit) and the widow(er) claims survivor benefits at FRA, the widow(er)'s benefit is reduced under the widow(er)'s limit provision. Under the widow(er)'s limit provision, which is intended to prevent the widow(er)'s benefit from exceeding the deceased worker's retirement benefit, the widow(er)'s benefit is limited to (1) the benefit the worker would be receiving if he or she were still alive, or (2) 82.5% of the worker's PIA, whichever is higher.93

Benefit Adjustments Based on Other Factors

Benefits for spouses and widow(er)s may be subject to other reductions, in addition to those based on entitlement before FRA. For example, under the dual entitlement rule, a Social Security spousal or widow(er)'s benefit is reduced or fully offset if the person also receives a Social Security retired-worker or disabled-worker benefit (see "Dually Entitled Beneficiaries" above). Similarly, under the government pension offset (GPO), a Social Security spousal or widow(er)'s benefit is reduced or fully offset if the person also receives a pension based on his or her own employment in certain federal, state or local government positions that are not covered by Social Security.94 In some cases, a spousal or widow(er)'s benefit may be reduced to bring the total amount of benefits payable to family members based on the worker's record within the maximum family benefit amount (see Appendix B, "Other Adjustments to Benefits").95

Under the Social Security retirement earnings test, auxiliary benefits may be reduced if the auxiliary beneficiary is below the FRA and has earnings above specified dollar thresholds. Also, under the RET, benefits paid to spouses may be reduced if the benefits are based on the record of a worker beneficiary who is affected by the RET (excluding benefits paid to divorced spouses who have been divorced for at least two years).

Table C-1 shows the percentage of a worker's PIA on which various categories of spousal and widow(er)'s benefits are based. It also shows the age at which benefits are first payable on a reduced basis (the eligibility age) and the maximum reduction to benefits claimed before FRA relative to the worker's PIA.

|

Basis for Entitlement |

Eligibility Age |

Basic Benefit Amount Before Any Adjustments |

Minimum Possible Benefit, Expressed as a Percent of the Worker's PIA0 |

|

Spouse |

Age 62, or Any age if caring for the child of a retired or disabled worker. The child must be under the age of 16 or disabled, and the child must be entitled to benefits. |

50% of worker's PIA |

32.5% of the worker's PIA (The figure of 32.5% is found as follows. The spousal benefit is 50% of the worker's PIA. A spouse who claims benefits at age 62 and has an FRA of 67 would have his or her spousal benefit reduced by 35%, as described in footnote 91. Mathematically, the calculation is (1-.35)*0.50 of the retired worker's benefit= 0.325. ) |

|

Divorced Spouse (The divorced individual must have been married to the worker for at least 10 years before the divorce became final.) |