This report provides background on teens and young adults in and exiting from foster care, and the federal support that is available to these youth as they transition to adulthood. It begins with a discussion of the characteristics of youth who have had contact with the child welfare system, including those who entered care, as well as those who exited care via emancipation because they have reached the legal age of majority. The report then provides an overview of the federal foster care system, including the Chafee Foster Care Independence program (CFCIP), and provisions in federal foster care law that are intended to help prepare youth for adulthood. The report goes on to discuss federal support for youth aging out of care in the areas of education, health care, employment, and housing. The report seeks to understand how states vary in their approaches to serving older youth in care and those who are recently emancipated. For example, 23 states, the District of Columbia, and five tribes are receiving federal funding to extend foster care to youth beyond age 18 (as of spring 2017).

Appendix A includes the state plan requirements under the CFCIP. Appendix B and Appendix C include funding data for the CFCIP.

Who Are Older Youth in Foster Care and Youth Aging Out of Care?

Children and adolescents can come to the attention of state child welfare systems due to abuse, neglect, or for some other reason, such as the death of a parent or child behavioral problems. Some children remain in their own homes and receive family support services, while others are placed in out-of-home settings. Such settings usually include a foster home, relative placement, or institution (e.g., residential treatment facility, maternity group home). A significant number of youth spend at least some time in foster care during their teenage years. They may also stay in care beyond age 18, up to age 21 (and sometimes beyond), if they are in a state that extends foster care. The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), which administers child welfare funding, collects data from states on the number and characteristics of children in foster care. On the last day of FY2015, approximately 126,000 youth and young adults comprised 29% of the foster care caseload nationally.1 These youth left foster care and were reunified with their parents or primary caretakers, adopted, or placed with relatives. However, 20,789 youth aged out that year, or were emancipated, when they reached the age of majority in their states, usually at age 18. The share of foster care youth emancipating was 9% in both FY2006 and FY2015 and between 10% and 11% in the intervening years.2

The Foster Care Dynamics report, a longitudinal study of children in 11 state child welfare systems from 2000 through 2005, provides detailed information about older youth who have been placed in out-of-home care.3 The study examined state administrative data to determine the typical trajectory of children across four age categories who first entered foster care during the five-year period, including teens ages 13 to 17. The study found that these teens tended to have shorter median lengths of stay relative to younger children; live in placements other than foster family homes (i.e., residential treatment facilities, group homes, etc.); experience more placements in their first year in care than younger children; and exit care through reunification, although running away and reaching the age of majority were exit pathways for about 10% to 24% of these older youth, depending on their age. More recent research shows that the majority of children in group care settings—or non-family settings ranging from those that provide specialized treatment or other services to more general care settings or shelters—are teenagers. In FY2013, approximately 7 out of 10 children in group care settings were ages 13 to 17.4

Youth who spend their teenage years in foster care and those who are likely to age out of care face challenges as they move to early adulthood. While in care, they may forego opportunities to develop strong support networks and independent living skills that their counterparts in the general population might more naturally acquire. Even older foster youth who return to their parents or guardians can still face obstacles, such as poor family dynamics or a lack of emotional and financial supports, that hinder their ability to achieve their goals as young adults. Perhaps the strongest evidence that youth who have spent at least some years in care during adolescence have not adequately made the transition to young adulthood is their poor outcomes across a number of domains.

Two studies—the Northwest Foster Care Alumni Study5 and the Midwest Evaluation of the Adult Functioning of Former Foster Youth6—have tracked outcomes for a sample of youth across several domains, either prospectively (following youth in care and as they age out and beyond) or retrospectively (examining current outcomes for young adults who had been in foster care) and comparing these outcomes to other groups of youth, either those who aged out and/or youth in the general population. The two studies indicate that youth who spent time in foster care during their teenage years tended to have difficulty as they entered adulthood and beyond.7 The Northwest Study looked at the outcomes of young adults who had been in foster care and found that they were more likely to have mental health and financial challenges than their peers generally. While they were just as likely to obtain a high school diploma, they were much less likely to obtain a bachelor's degree. The Midwest Evaluation has examined the extent to which outcomes in early adulthood are influenced by the individual characteristics of youth or their out-of-home care histories. The study has tracked the outcomes of youth who were in foster care since age 17 through age 26. Compared to their counterparts in the general population, youth in the Midwest study fare poorly in terms of education, employment, and other outcomes.

Separately, states have reported to HHS since FY2010 on the characteristics and experiences of certain current and former foster youth through the National Youth in Transition Database (NYTD). Among other data, states must report data on a cohort of foster youth beginning when they are age 17, and later at ages 19 and 21. Information is to be collected on a new group of foster youth at age 17 every three years. While the first cohort of NYTD respondents had some positive outcomes by age 21, about 43% reported having a homeless experience by age 21 and over one-quarter had, at some point during their lifetimes, been referred for substance abuse assessments or counseling.8

Despite the generally negative findings from the two major evaluations on youth aging out of foster care, many youth have demonstrated resiliency by overcoming obstacles, such as limited family support and financial resources, and meeting their goals. For example, youth in the Northwest study obtained a high school diploma or passed the general education development (GED) test at close to the same rates as 25- to 34-year-olds generally (84.5% versus 87.3%). Further, youth in the Midwest Evaluation were just as likely as the general youth population at age 23 or 24 to report being hopeful about their future.9

Overview of Federal Support for Foster Youth

The federal government recognizes that older youth in foster care and those aging out are vulnerable to negative outcomes and may ultimately return to the care of the state as adults, either through the public welfare, criminal justice, or other systems. Under the federal foster care program, states may seek reimbursement for youth to remain in care up to the age of 21. In addition, the federal foster care program has protections in place to ensure that older youth in care have a written case plan that addresses the programs and services they need in making the transition, among other provisions.

Separately, the John H. Chafee Foster Care Independence Program (CFCIP) provides mandatory funding for independent living services and supports (until age 21) to youth (1) who will likely age out of foster care without reunifying with their parents, being adopted, or being placed with relatives or other guardians; (2) youth who aged out between the ages of 18 and 21; and (3) youth age 16 or older who left foster care for kinship guardianship or adoption. Independent living services are intended to assist youth prepare for adulthood. The Chafee Education and Training Voucher (ETV) program separately authorizes discretionary funding for education and training vouchers for Chafee-eligible youth to cover their cost of postsecondary education (until age 21, or age 23 if they received a voucher at age 21). The Children's Bureau at HHS's Administration for Children and Families (ACF) administers the federal foster care program, CFCIP, and ETV program. As discussed in subsequent sections of this report, other federal programs are intended to help current and former youth in foster care make the transition to adulthood. Federal law authorizes funding for states and local jurisdictions to provide workforce support and housing to older foster youth and youth emancipating from care. As of January 1, 2014, states must also provide Medicaid coverage to eligible young people who age out of foster care.

Federal Foster Care

Historically, states have been primarily responsible for providing child welfare services to families and children that need them. While in out-of-home foster care, the state child welfare agency, under the supervision of the court (and in consultation with the parents or primary caretakers in some cases), serves as the child's parent and makes decisions on his or her behalf that are to promote his or her safety, permanence, and well-being.10 In most cases, the state relies on public and private entities and organizations to provide these services. The federal government plays a role in shaping state child welfare systems by providing funds and linking those funds to certain requirements.11

Federal support for foster care preceded, by several decades, the creation of the foster care program under Title IV-E of the Social Security Act in 1980 (P.L. 96-272). However, the 1980 law established this support as an independent funding source for states to provide foster homes for children in foster care. The law also stressed the importance of case planning and review to achieve permanence for foster children. Title IV-E requires states to follow certain case planning and management practices for all children in care. Title IV-B of the Social Security Act, which authorizes funding for child welfare services, includes related oversight provisions.

Title IV-E Reimbursement for Foster Care12

Title IV-E currently reimburses states for a part of the cost of providing foster care to eligible children and youth, who, because of abuse or neglect, cannot remain in their own homes and for whom a court has consequently given care and placement responsibility to the state. Under this program, a state may seek partial federal reimbursement to "cover the cost of (and the cost of providing) food, clothing, shelter, daily supervision, school supplies, a child's personal incidentals, liability insurance with respect to a child, and reasonable travel to the child's home for visitation and reasonable travel for the child to remain in the school in which the child is enrolled at the time of placement."13 Federal reimbursement to states under Title IV-E may be made only on behalf of a child who meets multiple federal eligibility criteria,14 including those related to the child's removal and the income and assets of the child's family. For purposes of this report, the most significant eligibility criteria for the federal foster care program are the child's age and placement setting. States may also seek reimbursement on behalf of Title IV-E eligible children for costs related to administration, case planning, training, and data collection.

Eligibility

Prior to FY2011, once a child reached his or her 18th birthday, he or she was no longer eligible for federal foster care assistance under Title IV-E.15 States have had the option, as of FY2011, to seek reimbursement for the cost of providing foster care to eligible youth until age 19, 20, or 21. The Fostering Connections to Success and Increasing Adoptions Act (P.L. 110-351) made this change by inserting a definition of "child" as it pertains to older youth in care.16 This definition specifies that a state may seek reimbursement for a "child" age 18 or older who is (1) completing high school or a program leading to an equivalent credential; (2) enrolled in an institution that provides post-secondary or vocational education; (3) participating in a program or activity designed to promote, or remove barriers to, employment; or (4) employed at least 80 hours per month. States may exempt youth from these requirements due to a medical condition as documented and updated in their case plan.

In program guidance, HHS advises that states and tribes can make remaining in care conditional upon whether youth pursue certain educational or employment pathways.17 For example, extended care could be provided just to those youth enrolled in post-secondary education. Still, the guidance advises that states and tribes should "consider how [they] can provide extended assistance to youth age 18 and older to the broadest population possible consistent with the law to ensure that there are ample supports for older youth." In other guidance, HHS has advised that youth can remain in foster care if they are married or enlisted in the military.18

As of April 2017, HHS has approved Title IV-E state plans for about half of all states (23), the District of Columbia, and five tribal nations to extend the maximum age of foster care.19 These 23 states are Alabama, Arkansas, California, Connecticut, Hawaii, Illinois, Indiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Nebraska, New York, North Dakota, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Texas, Washington, Virginia, West Virginia, and Wisconsin. The five tribal nations include Pascua Yaqui in Arizona; Eastern Band of Cherokee in North Carolina; Keweenaw Bay Indian Community in Michigan; Navajo Nation, which is in Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah; and Tolowa Dee-ni' Nation in California. (Other states extend foster care under certain circumstances; however, HHS has not approved amendments to their Title IV-E plan to allow these states to seek federal reimbursement for extended care.)20

All states with approved plan amendments, except for Indiana, extend care until age 21; Indiana extends care until age 20. Except for three states (Tennessee, West Virginia, and Wisconsin) and the Eastern Band of Cherokee, jurisdictions with approved plan amendments allow youth to remain in care under the four eligibility conditions and exempt youth from these conditions if a youth is incapable of meeting them for medical reasons. Tennessee allows youth to remain in care so long as youth are in school, or are incapable of performing these activities for medical reasons. West Virginia enables youth to remain in care if they are completing high school or completing a program leading to an equivalent credential. Wisconsin provides extended care to youth in postsecondary education who have a documented disability. The Eastern Band of Cherokee allows youth to remain in care under all of the conditions except the one related to medical reasons.

States and tribes may also provide Title IV-E subsidies on behalf of youth 18 or older (until age 19, 20, or 21, at the jurisdiction's option) who left foster care after age 16 for adoption or kinship guardianship, and meet the four eligibility conditions. This change was made by P.L. 110-351 by adding a definition of "child" to include youth up to the age of 21. Notably, HHS has advised that states can extend care to youth age 18 to 21 even if they were not in foster care prior to 18; and that young people can leave care and later return before they reach the maximum age of eligibility in the state (with certain requirements pertaining to how long youth can leave and remain eligible for foster care maintenance payments).21 In addition, state child welfare agencies can choose to close the original child abuse and neglect case and reopen the case as a "voluntary placement agreement" when the young person turns age 18 or if they reenter foster care between ages 18 and 21.22 In these cases, the income eligibility for Title IV-E would be based on only the young adult's income.23

Eligible Placement Setting

Federal reimbursement of part of the costs of maintaining children in foster care may be sought only for children placed in foster family homes or child care institutions; however, youth who remain in care beyond age 18 can live in a "supervised independent living setting.24 Foster family is not defined in law; a child care institution is defined as a private institution, or a public institution that accommodates no more than 25 children, and is approved or licensed by the state. States may not seek federal reimbursement of foster care costs for children who are in "detention facilities, forestry camps, training schools, or any other facility operated primarily for the detention of children who are determined to be delinquent."25

P.L. 110-351 directed HHS to establish in regulation what qualifies a "supervised independent living setting." In program instructions issued by HHS, the department stated that it did not have plans to issue regulations that describe the kinds of living arrangements considered to be independent living settings, how these settings should be supervised, or any other conditions for a young person to live independently. The instructions advised that states and tribes have the discretion to develop a range of supervised independent living settings that "can be reasonably interpreted as consistent with the law, including whether or not such settings need to be licensed and any safety protocols that may be needed."26

States appear to allow youth age 18 and older to live in a variety of settings. For example, in Minnesota youth can live in apartments, homes, dorms, and other settings. The state has explained that it is trying to determine how best to assist youth who pursue postsecondary education out of state, given that caseworkers must continue to meet with these youth at least once a month. Youth may live with roommates, and the state does not allow youth to live with their parent(s) from whom they were removed or significant others. The state does not require independent living settings to be licensed, and each county is given discretion on how to handle background checks for roommates and any safety concerns at the independent living setting.27

Case Planning and Review

Federal child welfare provisions under Title IV-B and Title IV-E of the Social Security Act require state child welfare agencies, as a condition of receiving funding under these titles, to provide certain case management services to all children in foster care. These include monthly case worker visits to each child in foster care;28 a written case plan for each child in care that documents the child's placement and steps taken to ensure their safety and well-being, including by addressing their health and educational needs;29 and procedures ensuring a case review is conducted not less often than every six months by a judge or an administrative review panel, and at least once every 12 months by a judge or administrative body who must consider the child's permanency plan of returning home or certain other outcomes specified in the law.30 Further, the court or administrative body conducting the hearings is to consult, in an age-appropriate manner, with the child regarding the proposed permanency plan or transition plan for the child.31

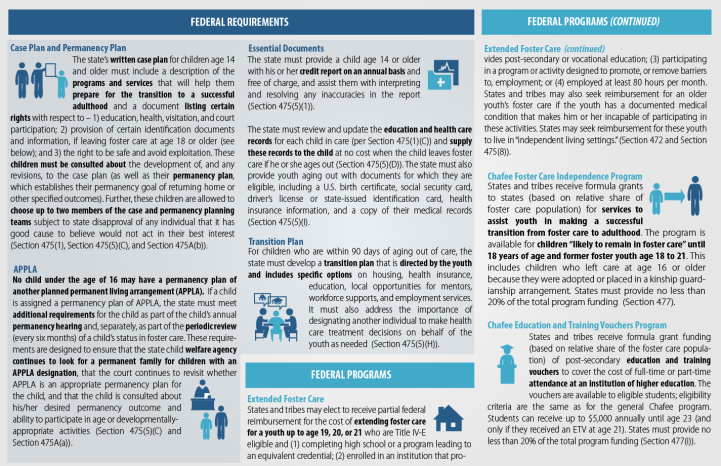

For youth age 14 and older, certain other provisions apply. For example, the written case plan must include a description of the programs and services that will help the child prepare for a successful transition to adulthood.32 These and related requirements, and applicable programs that apply to older youth in care, are summarized in Figure 1.

Chafee Foster Care Independence Program

The Chafee Foster Care Independence Program (CFCIP), authorized under Section 477 of the Title IV-E of the Social Security Act, provides services to older youth in foster care and youth transitioning out of care.33 This section provides an overview of the program, as well as information about program eligibility, youth participation, program administration, funding, data collection, and training and technical assistance.

Overview

The Foster Care Independence Act of 1999 (P.L. 106-169) replaced the prior-law Independent Living Program, established in 1985, with the John H. Chafee Foster Care Independence Program. The 1999 law doubled the annual mandatory funds available to states for independent living services from $70 million to $140 million.34 The purposes of the program are to

- identify children (youth) who are likely to remain in foster care until age 18 and provide them with support services to help make the transition to self-sufficiency;

- assist these youth to obtain employment and prepare for and enter college or other postsecondary training or educational institutions;

- provide personal and emotional support to youth aging out of foster care through mentors and other dedicated adults;

- enhance the efforts of former foster youth ages 18 to 21 to achieve self- sufficiency through supports that connect them to employment, education, housing, and other services;

- assure that youth receiving services recognize and accept personal responsibility for preparing for and then making the transition from adolescence to adulthood;

- make education and training vouchers, including postsecondary training and education, available to youth who have aged out of foster care;

- provide services to youth who, after attaining 16 years of age, have left foster care for kinship guardianship or adoption; and

- ensure that youth who are likely to remain in foster care until 18 years of age have regular, ongoing opportunities to engage in age- or developmentally appropriate activities.

States may use CFCIP funding to provide services listed in the authorizing statute. CFCIP-funded services may consist of educational assistance, vocational training, mentoring, and preventive health activities, among other services. States may dedicate as much as 30% of their program funding toward room and board for youth ages 18 to 21, including for those youth who are enrolled in an institution of higher education or who remain in foster care in states that provide care to youth until ages 19, 20, or 21.35 Room and board are not defined in statute, but they typically include food and shelter, and may include rental deposits, rent, utilities, and the cost of household startup purchases. CFCIP funds may not be used to acquire property to provide housing to current or former foster youth.36 Also, as described in HHS's Child Welfare Policy Manual, states may use CFCIP funding to establish trust funds for youth eligible under the program.37 Youth are eligible for an education and training voucher (until age 23) if they are eligible for the Chafee program. Youth who qualify for the CFCIP, including youth who left foster care at age 16 or older for kinship guardianship or adoption, are eligible for the Chafee Education and Training Voucher (ETV) Program.

Eligibility for CFCIP Benefits and Services

The CFCIP requires states to ensure that independent living programs serve children of "various ages and various stages of achieving independence" and use objective criteria for determining eligibility for benefits and services under the program. It further specifies that states are to provide services under the CFCIP for children who are "likely to remain in foster care until 18 years of age," "aging out of foster care," "and youth after attaining 16 years of age, have left foster care for kinship guardianship or adoption."

The number of youth who receive independent living program assistance with CFCIP dollars and/or other independent living dollars is collected by HHS via states through a database known as the National Youth in Transition Database (NYTD, discussed further in a following section).38 Separately, states reported to HHS that they provided ETV vouchers to 16,400 youth in FY2008; 16,650 youth in FY2009; 17,400 youth in program year (PY) 2010; 17,100 youth in PY2011; 16,554 youth in PY2012; and 16,548 in PY2013.39

Youth Likely to Remain in Foster Care Until Age 18

Under the former Independent Living Program, states could provide services to current foster youth ages 16 and 17 who were eligible for Title IV-E foster care maintenance payments, or to "other children in care," regardless of Title IV-E status. The law establishing the CFCIP removed reference to a minimum eligibility age and required states to provide supports to children "likely to remain in foster care" until age 18. This phrase is not defined in the act, and states are to create eligibility standards using objective criteria. States can provide services to any child age 17 and younger regardless of their placement in a kinship care home, family foster home, pre-adoptive home, or any other state-sanctioned placement so long as the child is in state custody. HHS's Child Welfare Policy Manual specifies that states are to fund independent living services for foster youth ages 16 to 18 regardless of their placement in another state.40

A 2008 survey of independent living coordinators in 45 states (including the District of Columbia) by the Chapin Hall Center for Children at the University of Chicago found that in about half of the states (24, 53.3%), youth as young as age 14 were eligible for CFCIP-funded services. Seven states provide these services at a younger age, while 13 provide services at an older age. One state said that the age depended on the county, and another state did not report on the minimum age for services.41 Nearly all (40) of the surveyed states reported that foster youth were eligible for CFCIP-funded services regardless of their permanency plan.

Youth Aging Out of Foster Care

Prior to the enactment of the CFCIP, states had the option to serve young people who had emancipated from care until age 21. The Foster Care Independence Act requires states that receive CFCIP funds to provide independent living services to youth who have aged out of care between the ages of 18 through 21. According to HHS, this requirement does not preclude states from providing services to other former foster care youth ages 18 to 21 who exited care prior to their 18th birthday.42 States can use the Chafee program to provide services for youth who left foster care at age 16 or older for kinship guardianship or adoption.

The 2008 Chapin Hall survey of 45 states found that almost half of the states (19; 42.2%) reported that former foster youth are eligible for aftercare services if they were not in care on their 18th birthday. Slightly more states (about 21) reported that these youth could receive services if their discharge outcome was reunification, adoption, or legal guardianship.43

Former foster youth continue to remain eligible for aftercare services until age 21 if they move to another state. The state in which the former foster youth resides—whether or not the youth was in foster care in that state—is responsible for providing independent living services to the eligible young person.44

American Indian Youth

The prior federal Independent Living Program did not specify that states consult with American Indian tribes or serve Indian youth in particular. The CFCIP requires that a state must certify that each federally recognized Indian tribal organization in the state has been consulted about that state's independent living programs and that there have been efforts to coordinate the programs with these tribes. In addition, the CFCIP provides that the "benefits and services under the programs are to be made available to Indian children in the state on the same basis as to other children in the state." "On the same basis" has been interpreted by HHS to mean that the state will provide program services equitably to children in both state custody and tribal custody.45 The importance of tribal involvement was explained by Representative J.D. Hayworth during debate of the House version of P.L. 106-169 (H.R. 1802) in June 1999, when he said that tribes are in the best position to identify the needs of tribal youth and local resources available for these young people.46

An Indian tribe, tribal organization, or tribal consortium may apply to HHS and receive a direct federal allotment of CFCIP and/or ETV funds. To be eligible, a tribal entity must be receiving Title IV-E funds to operate a foster care program (under a Title IV-E plan approved by HHS or via a cooperative agreement or contract with the state). Successful tribal applicants are to receive an allotment amount(s) out of the state's allotment for the program(s) based on the share of all children in foster care in the state under tribal custody. Tribal entities must satisfy the CFCIP program requirements established for states, as HHS determines appropriate. They must submit a plan to HHS that details their process for consulting with the state about their independent living or ETV programs, among other information, through what is known as the Child and Family Services Plan (CFSP) and annual updates to that plan. Four tribes—Prairie Band of Potawatomi (Kansas), Santee Sioux Nation (Nebraska), Confederated Tribe of Warm Springs (Oregon), and Port Gamble S'Klallam Tribe (Washington)—receive CFCIP and ETV funds.

A state must certify that it will negotiate in good faith with any tribal entity that does not receive a direct federal allotment of child welfare funds but would like to enter into an agreement or contract with the state to receive funds for administering, supervising, or overseeing CFCIP and ETV programs for eligible Indian children under the tribal entity's authority.

The Role of Youth Participants

The CFCIP requires that states ensure youth in independent living programs participate directly in designing their own program activities that prepare them for independent living and further that they "accept personal responsibility for living up to their part of the program." This language builds on the positive youth development approach to serving youth.47 Youth advocates that support this approach view youth as assets and promote the idea that youth should be engaged in decisions about their lives and communities.

States have also taken various approaches to involving young people in decisions about the services they receive. These include annual conferences, with young people involved in conference planning and participation; youth speakers' bureaus, with young people trained and skilled in public speaking; youth or alumni assisting in the recruitment of foster and adoptive parents; and young people serving as mentors for children and youth in foster care, among other activities.48 Most states have also established formal youth advisory boards to provide a forum for youth to become involved in issues facing youth in care and aging out of care.49 Youth-serving organizations for current and former foster youth, such as Foster Club, provide an outlet for young people to become involved in the larger foster care community and advocate for other children in care. States are not required to utilize life skills assessments or personal responsibility contracts with youth to comply with the youth participation requirement, although some states use these tools to assist youth in making the transition to adulthood.50

Program Administration

States administer their independent living programs in a few ways. Some programs are overseen by the state independent living office, with an independent living coordinator and other program staff. For example, in Maine the state's independent living manager oversees specialized life skills education coordinators assigned to cover all of the state's district offices for the Department of Health and Human Services. In some states, like California, each county (or other jurisdiction) administers its own program with some oversight and support from a statewide program. Other states, including Florida, use contracted service providers to administer their programs. Many jurisdictions have partnered with private organizations to help fund and sometimes administer some aspect of their independent living programs. For example, the Jim Casey Youth Opportunities Initiative has provided funding and technical assistance to multiple cities to provide financial support and training to youth exiting care.51

Chafee Education and Training Vouchers

Vouchers are available for youth who qualify for the CFCIP to cover the cost of (full-time or part-time) attendance at an institution of higher education, as defined by the Higher Education Act of 1965 (HEA). HEA defines "cost of attendance" as tuition, fees, and other equipment or materials required of all students in the same course of study; books, supplies, and allowance for transportation and miscellaneous personal expenses, including computers; room and board; child care expenses for a student who is a parent; accommodations related to the student's disability that are not paid for by another source; expenses related to the youth's work experience in a cooperative education program (alternating periods of academic study and employment to give students work experience); and student loan fees or insurance premiums on the loans.52 HEA defines "institutions of higher education" to include traditional higher education institutions (e.g., public or private, nonprofit two- and four-year colleges and universities) as well as other postsecondary institutions (e.g., proprietary or for-profit schools offering technical training programs, and postsecondary vocational schools).53

Youth are eligible to receive ETVs until age 21, except that youth receiving a voucher at age 21 may continue to participate in the voucher program until age 23 if they are enrolled in a postsecondary education or training program and are making satisfactory progress toward completion of that program. Given the age restriction, this may preclude former foster youth who delay college enrollment or are applying to graduate school from receiving the voucher.

Funding received through the ETV program does not count toward the student's expected family contribution, which is used by the federal government to determine a student's need for federal financial aid. However, the total amount of education assistance provided under the ETV program and other federal programs may not exceed the total cost of attendance, and students cannot claim the same education expenses under multiple federal programs.54 In addition, a current fiscal year's ETV funds may not be used to finance a youth's educational or vocational loans incurred prior to that current fiscal year.55

ETV Program Administration

The ETV program is administered by HHS, which provides funding to states to carry out the program. The state with the placement and responsibility for a youth in foster care is to provide the voucher to that youth. The state must also continue to provide a voucher to any youth who is currently receiving a voucher and moves to another state for the sole purpose of attending an institution of higher education. If a youth permanently moves to another state after leaving care and subsequently enrolls in a qualified institution of higher education, the state where he or she resides would provide the voucher.56

Generally, states administer their ETV program through their independent living program. Some states, however, administer the program through their financial aid office (e.g., California Student Aid Commission) or at the local level (e.g., Florida, where all child welfare programs are administered through community-based agencies). Some states contract with a nonprofit service provider, such as the Foster Care to Success or the Student Assistance Foundation.

States and counties may use ETV dollars to fund the vouchers and the costs associated with program administration, including for salaries, expenses, and training of staff who administer the state's voucher program. States are not permitted to use Title IV-E foster care or adoption assistance program funds for administering the ETV program.57 They may, however, spend additional funds from state sources or other sources to supplement the ETV program or use ETV funds to expand existing postsecondary funding programs.58 Several states have scholarship programs, tuition waivers, and grants for current and former foster youth that are funded through other sources.59

Funding for States

States must provide a 20% match (in-kind or cash) to receive their full federal CFCIP and ETV allotment. CFCIP funds are often mixed with state, local, and other funding sources to provide a system of support for youth likely to age out of care and those who have emancipated. The 2008 survey of 45 states by Chapin Hall found that 31 of the states (68.9%) spend additional funds—beyond the 20% match—to provide independent living services and supports to eligible youth.60 Of the 31 states, 22 reported that they used funds to provide services for which CFCIP dollars cannot be used.61

To be eligible for CFCIP general and ETV funds, a state must submit a five-year plan (as part of what is known as the Child and Family Service Plan (CFSP) and Annual Progress and Service Report (APSR)) to HHS that describes how it intends to carry out its independent living program. Appendix A includes the full list of certifications that the state must make when submitting its plan. The plan must be submitted on or before June 30 of the calendar year in which the plan is to begin. States may make amendments to the plan and notify HHS within 30 days of modifying the plan. HHS is to make the plans available to the public.

CFCIP and ETV funds are distributed to each state based on its proportion of the nation's children in foster care. Appendix B provides the CFCIP and ETV allotments for each state (and for a small number of tribes) in FY2016 and FY2017.

Hold Harmless Provision

The CFCIP includes a "hold harmless" clause that precludes any state from receiving less than the amount of general independent living funds it received under the former independent living program in FY1998 or $500,000, whichever is greater. There is no hold harmless provision for ETV funds. The general funding for independent living services doubled nationally with the enactment of the CFCIP; however, the percentage change in funds received varies across states. This is because the distribution of funding was changed to reflect the most current state share of the national caseload (instead of their share of the 1984 caseload in all previous years).

Unused Funds

States have two fiscal years to spend their CFCIP and ETV funds. If a state does not apply for all of its allotment, the remaining funds may be redistributed among states that need these funds as determined by HHS. If a state applies for all of its CFCIP allotted funds but does not spend them within the two-year time frame, the unused funds revert to the federal Treasury. Table C-1 in Appendix C shows the percentage and share of funds returned for both programs from FY2005 through FY2014, as well as a list of jurisdictions that have returned these funds.

Training and Technical Assistance

Until FY2015, training and technical assistance grants for the CFCIP and the ETV program were awarded competitively every five years, with non-competitive grants renewed annually with this period. The most recent cooperative agreement under the old system was made for FY2010 through FY2014. The National Child Welfare Resource Center for Youth Development (NCWRCYD), housed at the University of Oklahoma, provided assistance under the grant. Beginning with FY2015, HHS has operated the Child Welfare Capacity Building Collaborative. HHS has contracted with ICF International, a policy management organization, to provide training and technical assistance on a number of child welfare issues, including youth development.62

National Youth in Transition Database (NYTD)

The CFCIP requires that HHS consult with state and local public officials responsible for administering independent living and other child welfare programs, child welfare advocates, Members of Congress, youth service providers, and researchers to (1) "develop outcome measures (including measures of educational attainment, high school diploma, avoidance of dependency, homelessness, non-marital childbirth, incarceration, and high-risk behaviors) that can be used to assess the performance of states in operating independent living programs"; (2) identify the data needed to track the number and characteristics of children receiving services, the type and quantity of services provided, and state performance on the measures; and (3) develop and implement a plan to collect this information beginning with the second fiscal year after the passage of the law establishing the CFCIP.

In response to these requirements, HHS created the National Youth in Transition Database (NYTD). The final rule establishing the NYTD became effective April 28, 2008, and it required states to report data on youth beginning in FY2011.63 HHS uses NYTD to engage in two data collection and reporting activities.64 First, states collect demographic and information about receipt of services on eligible youth who currently receive independent living services. This includes youth regardless of whether they continue to remain in foster care, were in foster care in another state, or received child welfare services through an Indian tribe or privately operated foster care program. Second, states track information on outcomes of foster youth on or about their 17th birthday, two years later on or about their 19th birthday, and again on or about their 21st birthday.

Consistent with the statutory requirement developed by Congress in the CFCIP authorizing statute, HHS is to penalize any state not meeting the data collection procedures for the NYTD from 1% to 5% of its annual Chafee fund allotment, which includes any allotted or re-allotted funds for the general CFCIP program only. The penalty amount is to be withheld from a current fiscal year award of the funds. HHS is to evaluate a state's data file against data compliance standards, provided by statute. However, states have the opportunity to submit corrected data.65

Evaluation of Innovative Independent Living Programs

Research is limited on the efficacy of independent living and related programs for youth in and aging out of foster care. The CFCIP provides that HHS is to conduct evaluations of independent living programs funded by the CFCIP deemed to be innovative or of national significance. The law reserves 1.5% of total CFCIP funding annually for these evaluations, as well as CFCIP-related technical assistance, performance measurement, and data collection. HHS conducted an evaluation of promising independent living programs, and is in the process of identifying new ways of conducting research in this area.

For the initial evaluation, HHS contracted with the Urban Institute and its partners to conduct what is known as the Multi-Site Evaluation of Foster Youth Programs.66 The goal of the evaluation was to determine the effects of independent living programs funded by the CFCIP authorizing statute in achieving key outcomes, including increased educational attainment, higher employment rates and stability, greater interpersonal and relationship skills, reduced non-marital pregnancy and births, and reduced delinquency and crime rates. HHS and the evaluation team initially conducted an assessment to identify programs that could be evaluated rigorously, through random assignment to treatment and control groups, as required under the law. Their work is the first to involve random assignment of programs for this population.

The evaluation team examined four programs in California and Massachusetts—an employment services program in Kern County, CA; a one-on-one intensive, individualized life skills program in Massachusetts; and a classroom-based life skills training program and tutoring/mentoring program, both in Los Angeles County, CA. The evaluation of the Los Angeles and Kern County programs found no statistically significant impacts as a result of the interventions; however, the life skills program in Massachusetts showed impacts for some of the education outcomes that were measured.

The Massachusetts program is known as the Massachusetts Adolescent Outreach Program for Youth in Intensive Foster Care, or Outreach.67 Outreach assists youth who enroll voluntarily in preparing to live independently and in having permanent connections to caring adults upon exiting care. Outreach youth were more likely than their counterparts in the control group to report having ever enrolled in college and they were more likely to stay enrolled. Outreach youth were also more likely to experience outcomes that were not a focus of the evaluation: youth were more likely to remain in foster care and to report receiving more help in some areas of educational assistance, employment assistance, money management, and financial assistance for housing. In short, the Outreach youth may have been less successful on the educational front if they had not stayed in care. Youth in the program reported similar outcomes as the control group for multiple other measures, including in employment, economic well-being, housing, delinquency, pregnancy, or preparedness for various tasks associated with living on one's own.

Emerging Research

HHS has contracted with the Urban Institute and Chapin Hall for additional research on the Chafee program. Citing the lack of experimental research in child welfare, the research team is examining various models in other policy areas that could be used to better understand promising approaches of working with older youth in care and those transitioning from care. Researchers have identified a conceptual framework that takes into account the many individual characteristics and experiences that influence youth's ability to transition successfully into adulthood, as well as trauma from maltreatment and other experiences that may influence this transition.68 In addition, researchers have published a series of briefs that discuss outcomes and programs for youth in foster care in the areas of education, employment, and financial literacy. The briefs discuss that few programs have impacts for foster youth in these areas. The briefs also address issues to consider when designing and evaluating programs for youth in care.69

Related Research

Related research, conducted by the social research organization MDRC, has used random assignment to evaluate whether an independent living program for youth who were formerly in care (or the juvenile justice system) in Tennessee has promising outcomes. The program, YVLifeSet at Youth Villages, provides intensive, individualized case management provided by a case manager who has eight clients. Over a nine-month period, youth receive support for employment, education, housing, mental or physical health, and life skills. The evaluation of youth outcomes after one year following their enrollment in the study found that compared to their peers, youth who had been randomly assigned to the program had greater earnings, increased housing stability and economic well-being, and some improved outcomes related to health and safety. These youth did not have improved outcomes in the areas of education, social support, or criminal involvement.70

Other Federal Support for Older Current and Former Foster Youth

In addition to the federal programs under Title IV-E, other federal programs provide assistance to older current and former foster youth. This section describes a Medicaid pathway for certain former foster youth; educational, workforce, and housing supports; and a grant to fund training for child welfare practitioners working with older foster youth and youth emancipating from care.

Medicaid71

In the Foster Care Independence Act that established the Chafee Foster Care Independence program, Congress encouraged states to provide Medicaid coverage to children who were aging out of the foster care system. The law created a new optional Medicaid eligibility pathway for "independent foster care adolescents"; this pathway is often called the "Chafee option."72 The law further defined these adolescents as individuals under the age of 21 who were in foster care under the responsibility of the state on their 18th birthday. Within this broadest category of independent foster care adolescents, the law permits states to restrict eligibility based on the youth's income or resources, and whether or not the youth had received Title IV-E funding.

As of late 2012, more than half (30) of all states had extended the Chafee option to eligible youth. Of these states, five reported requiring youth to have income less than a certain level of poverty (180% to 400%). Four states permitted youth who were in foster care at age 18 in another state to be eligible under the pathway. States also reported whether the youth is involved in the process for enrolling under the Chafee option. In 15 states, youth are not directly involved in the enrollment process. For example, some states automatically enroll youth. In the other 15 states, youth are involved in enrollment with assistance from their caseworker or they enroll on their own. Most states that have implemented the Chafee option require an annual review to verify that youth continue to be eligible for Medicaid. States generally have a hierarchy to determine under which pathway youth qualify. For example, in most states, youth who qualify for the Chafee option and receive Supplemental Security Income (SSI) would be eligible for Medicaid under the SSI Medicaid pathway.73

As of January 1, 2014, certain former foster youth are eligible for Medicaid under a specific mandatory pathway created for this population in the Affordable Care Act (ACA). Former foster youth are eligible if they meet the following requirements:

- are under 26 years of age;

- were not eligible or enrolled under existing Medicaid mandatory eligibility groups, or described in any of the existing Medicaid mandatory eligibility groups, but have income that exceeds the upper income eligibility limit established under any such group;

- were in foster care under the responsibility of the state on the date of attaining 18 years of age (or 19, 20, or 21 years of age if the state extends federal foster care to that older age); and

- were enrolled in the Medicaid state plan or under a Medicaid waiver while in foster care.

The ACA specifies that income and assets are not considered when determining eligibility for the new eligibility group of former foster care youth. Youth age 18 and older who were formerly in care and do not qualify under the pathway for former foster youth may be eligible for Medicaid under other mandatory pathways available to adults generally. For example, if former foster youth meet certain income and other criteria, they may qualify under the pathways available to low-income pregnant women and adults with disabilities who are eligible for SSI.

As of the date of this report, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) had not issued a final rule with regard to the new Medicaid eligibility group for former foster youth who aged out of foster care. However, in January 2013 it proposed rules for this group and in December 2013 it provided some clarifying guidance. This guidance notes that any youth who was in foster care—as that term is defined in federal child welfare regulations—may qualify for the new former foster youth Medicaid eligibility group. This includes youth who were in the care and placement responsibility of a state or tribal child welfare agency without regard to whether the youth received Title IV-E assistance or were placed in licensed or unlicensed foster care living arrangements. Additionally, the proposed rule interpreted the law to mean that a youth must be enrolled in Medicaid at the time he or she ages out of foster care (as opposed to at any time while the child was in foster care).

The subsequent guidance also explained that states have flexibility in determining the process for verifying that youth were in foster care receiving Medicaid at age 18 (or a later age if applicable), and may allow youth to attest to this themselves. Separately, the subsequent guidance clarified that individuals who would qualify for Medicaid under both the group for former foster youth and the low-income adult category must be enrolled under the group for former foster youth.

HHS advised that the new Medicaid option does not completely supersede the Chafee pathway. For example, states may continue to use this pathway to cover any youth who turned age 18 in foster care and were not enrolled in Medicaid.74 The guidance further advised that states are not required to cover eligible foster youth who aged out of care in another state; however, CMS signaled that it would approve state plan amendments to cover these youth. In addition, youth are eligible if they were in foster care at age 18 prior to January 2014, and meet the other eligibility criteria.75

Former foster youth may also qualify for Medicaid through other eligibility pathways available to certain groups of adults, such as for pregnant women with family income equal to or less than 133% of the federal poverty limit (FPL), some low-income adults with children, and some adults with high medical expenses (i.e., "medically needy"). These youth may also be eligible for Medicaid or CHIP coverage through waivers, known as Section 1115 waivers, which provide comprehensive coverage to categorically ineligible adults with incomes up to at least 100% of the FPL.

Educational Support

Federal funding and other supports for current and former foster youth are in place to help these youth aspire to, pay for, and graduate from college. The Higher Education Act (HEA) authorizes financial aid and support programs that target this population, among other vulnerable populations. 76

Federal Financial Aid

For purposes of applying for federal financial aid, a student's expected family contribution (EFC) is the amount, according to the federal need analysis methodology, that can be expected to be contributed by a student and the student's family toward his or her cost of education. Certain groups of students are considered "independent," meaning that only the income and assets of the student are counted.77 Individuals under age 24 who are or were orphans, in foster care, or wards of the court at age 13 or older are eligible to apply for independent student status.78 The law does not specify the length of time that the youth must have been in foster care or the reason for exiting as factors for eligibility to claim independent status; however, the federal financial aid form, known as the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA), instructs current and former foster youth that the financial aid administrator at their school may require the student to provide proof that they were in foster care.

The FY2014 appropriations law (2014, P.L. 113-76) amended the Higher Education Act to direct the Department of Education (ED) to modify the FAFSA form so that it includes a box for applicants to identify whether they are or were in foster care, and to require ED to provide these applicants with information about federal educational resources that may be available to them.79

TRIO Programs

The Higher Education Act (HEA) authorizes services, including housing services, among other related supports, specifically for youth in foster care or recently emancipated youth.80 The act provides that youth in foster care, including youth who have left foster care after reaching age 16, and homeless children and youth are eligible for what are collectively called the federal TRIO programs. The programs are known individually as Talent Search, Upward Bound, Student Support Services, Educational Opportunity Centers, and McNair Postbaccalaureate. The TRIO programs are designed to identify potential postsecondary students from disadvantaged backgrounds, prepare these students for higher education, provide certain support services to them while they are in college, and train individuals who provide these services. HEA directs the Department of Education (ED), which administers the programs, to (as appropriate) require applicants seeking TRIO funds to identify and make available services, including mentoring, tutoring, and other services, to these youth.81 In addition, HEA authorizes services for current and former foster youth (and homeless youth) through Student Support Services—a program intended to improve the retention and graduation rates of disadvantaged college students—that include temporary housing during breaks in the academic year.82 TRIO funds are awarded by ED on a competitive basis. In FY2017, Congress appropriated $900 million to TRIO programs.83

Separately, HEA allows additional uses of funds through the Fund for the Improvement of Postsecondary Education (FIPSE) to establish demonstration projects that provide comprehensive support services for students who were in foster care (or homeless) at age 13 or older.84 FIPSE is a grant program that seeks to support the implementation of innovative educational reform ideas and evaluate how well they work. As specified in the law, the projects can provide housing to the youth when housing at an educational institution is closed or unavailable to other students. Congress appropriated $67.8 million to FIPSE for FY2015; no funds were appropriated for FY2016 or FY2017.85

Workforce Support

Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act Programs

The Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA) authorizes job training programs to unemployed and underemployed individuals through the Department of Labor (DOL). Two of these programs—Youth Activities and Job Corps—provide job training and related services to targeted low-income vulnerable populations, including foster youth.86 The Youth Activities program focuses on preventive strategies to help in-school youth stay in school and receive occupational skills, as well as on providing training and supportive services, such as assistance with child care, for out-of-school youth.87 Job Corps is an educational and vocational training program that helps students learn a trade, complete their GED, and secure employment. To be eligible, foster youth must meet age and income criteria as defined under the act. Young people currently or formerly in foster care may participate in both programs if they are ages 14 to 24.88 In FY2017, Congress appropriated $873 million to Youth Activities and $1.7 billion to Job Corps.89

Housing Support

Family Unification Vouchers Program

Current and former foster youth may be eligible for housing subsidies provided through programs administered by the Department of Housing and Urban Development's (HUD's) Family Unification Vouchers program (FUP vouchers). The FUP vouchers were initially created in 1990 under P.L. 101-625 for families that qualify for Section 8 tenant-based assistance and for whom the lack of adequate housing is a primary factor in the separation, or threat of imminent separation, of children from their families or in preventing the reunification of the children with their families.90 Amendments to the program in 2000 under P.L. 106-377 made youth ages 18 to 21 who left foster care at age 16 or older eligible for the vouchers for up to 18 months. The Housing Opportunity Through Modernization Act (P.L. 114-201), enacted in July 2016, extended the upper age of eligibility for FUP vouchers, from 21 to 24, for youth who emancipated from foster care. It also extended assistance under the program for these youth from 18 to 36 months and allows the voucher assistance to begin 90 days prior to a youth leaving care because they are aging out. It also requires HUD, after consulting with other appropriate federal agencies, to issue guidance to improve coordination between public housing agencies, which administer the vouchers, and child welfare agencies. The guidance must address certain topics, including identifying eligible recipients for FUP vouchers, coordinating with other local and family providers participating in the Continuum of Care,91 implementing housing strategies to assist eligible families and youth, aligning system goals to improve outcomes for families and youth, and identifying child welfare resources and supportive families for families and youth.

FUP vouchers were initially awarded from 1992 to 2001. Over that period, approximately 39,000 vouchers were distributed.92 Each award included five years of funding per voucher and the voucher's use was restricted to voucher-eligible families for those five years. At the end of those five years, PHAs were eligible to convert FUP vouchers to regular Section 8 housing vouchers for low-income families. While the five-year use restrictions have expired for all family unification vouchers, some PHAs may have continued to use their original family unification vouchers for FUP-eligible families and some may have chosen to use some regular-purpose vouchers for FUP families. Congress appropriated $20 million for new FUP vouchers in each of FY2008 and FY2009; $15 million in FY2010; and $10 million in FY2017.93 Congress has specified that amounts made available under Section 8 tenant-based rental assistance and used for the FUP vouchers are to remain available for the program.

A 2014 report on the FUP program examined the use of FUP vouchers for foster youth. The study was based on a survey of PHAs, a survey of child welfare agencies that partnered with PHAs that served youth, and site visits to four areas that use FUP to serve youth. The survey of PHAs showed that slightly less than half of PHAs operating FUP had awarded vouchers to former foster youth in the 18 months prior to the survey. PHAs reported that youth were able to obtain a lease within the allotted time, and many kept their leases for the full 18-month period they were eligible for the vouchers. In addition, 14% of total FUP program participants qualified because of their foster care status. According to the study, this relatively small share was due to the fact that less than half of PHAs were serving youth, and these PHAs tended to allocate less than one-third of their vouchers to youth. PHAs that provide FUP vouchers indicated that they most often did not provide them to youth due to a lack of referrals. In addition, about half of child welfare agencies working with PHAs reported that they do not refer all FUP-eligible youth they identify. This may be due to the financial burden of providing youth with supportive services, as required under the law. Of the child welfare agencies working with PHAs, 40% indicated that cost was somewhat a challenge or a major challenge in referring youth. Child welfare agencies also reported concerns that the FUP vouchers do not necessarily lead to permanency for these youth and that the 18-month time limit is too short.94

Other Support

Older current and former foster youth may be eligible for housing services and related supports through the Runaway and Homeless Youth program, administered by HHS.95 The program is comprised of three subprograms: the Basic Center program (BCP), which provides short-term housing and counseling to youth up to the age of 18; the Transitional Living program (TLP), which provides longer-term housing and counseling to youth ages 16 through 22; and the Street Outreach program (SOP), which provides outreach and referrals to youth who live on the streets. Youth transitioning out of foster care may also be eligible for select transitional living programs administered by HUD, though the programs do not specifically target these youth.

The Foreclosure Prevention Act of 2008 (P.L. 110-289) was signed into law on July 30, 2008, and enables owners of properties financed in part with Low-Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTCs) to claim as low-income units those occupied by low-income students who were in foster care. Owners of LIHTC properties are required to maintain a certain percentage of their units for occupancy by low-income households; students (with some exceptions) are not generally considered low-income households for this purpose. The law does not specify the length of time these students must have spent in foster care nor require that youth are eligible only if they emancipated.

Appendix A. State Plan Requirements Under the Chafee Foster Care Independence Program (CFCIP)

To receive funds under the CFCIP, a state must describe in its CFCIP plan how it will

- design and deliver programs to achieve the program purposes;

- ensure statewide, although not necessarily uniform, coverage by the program;

- ensure that the programs serve children of various ages and at various stages of achieving independence;

- involve the public and private sectors in helping adolescents in foster care achieve independence;

- use objective criteria for determining eligibility for and ensuring fair and equitable treatment of benefit recipients; and

- cooperate in national evaluations of the effects of the programs in achieving the purpose of the CFCIP.

The state must also certify that it will

- provide assistance and services to eligible former foster youth;

- use room and board payments only for youth ages 18 to 21;

- expend not more than 30% of CFCIP funds on room and board for youth ages 18 to 21;

- use funding under the Title IV-E Foster Care program and Adoption Assistance program (but not the CFCIP) to provide training to help foster parents and others understand and address the issues confronting adolescents preparing for independent living and coordinate this training, where possible, with independent living programs;

- consult widely with public and private organizations in developing the plans and give the public at least 30 days to comment on the plan;

- make every effort to coordinate independent living programs with other youth programs at the local, state, and federal levels, including independent living projects funded under the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act, abstinence education programs, local housing programs, programs for disabled youth, and school-to-work programs offered by high schools or local workforce agencies;

- consult each Indian tribe about the programs to be carried out under the plan, ensure that there have been efforts to coordinate the programs with such tribes, and ensure that benefits and services under the programs will be made available to Indian children in the state on the same basis as other children in the state (beginning in FY2010, states must also negotiate in good faith with any tribal entity that does not receive a direct federal allotment of child welfare funds but would like to enter into an agreement or contract with the state to receive funds for administering, supervising, or overseeing CFCIP and ETV programs for eligible Indian children under the tribal entity's authority);

- ensure that eligible youth participate directly in designing their own program activities that prepare them for independent living and that they accept personal responsibility for living up to their part of the program;

- establish and enforce standards and procedures to prevent fraud and abuse in the programs carried out under its plan;

- ensure that the ETV program complies with the federal program requirements, including that (1) the total amount of education assistance to a youth provided through the ETV program and under other federal and federally supported programs does not exceed the total cost of attendance, and (2) it does not duplicate benefits under the CFCIP or other federal or federally assisted benefit programs; and

- ensure that eligible youth receive education about (1) the importance of designating an individual to make health care treatment decisions for them (should they become unable to do so, have no relatives authorized under state law to do so, or do not want relatives to make those decisions); (2) whether a health care power of attorney, health care proxy, or other similar document is recognized under state law; and (3) how to execute such a document.

Appendix B. Funding for the Chafee Foster Care Independence Program (CFCIP) and Education and Training Voucher (ETV) Program

Table B-1. FY2016 and FY2017 CFCIP General and ETV Allotments by State

Funding in nominal dollars; excludes funding for CFCIP technical assistance and ETV set-asides

|

FY2016 Chafee |

FY2016 ETV |

FY2016 Total |

FY2017 Chafee |

FY2017 ETV |

FY2017 Total |

|

|

States |

||||||

|

Alabama |

$1,441,038 |

$467,620 |

1,908,658 |

$1,441,886 |

$470,954 |

$1,912,840 |

|

Alaska |

$692,685 |

$224,778 |

$917,463 |

$806,180 |

$263,317 |

$1,069,497 |

|

Arizona |

$5,138,520 |

1,667,463 |

$6,805,983 |

$5,390,133 |

$1,760,542 |

$7,150,675 |

|

Arkansas |

$1,203,817 |

$390,642 |

$1,594,459 |

$1,382,024 |

$451,401 |

$1,833,425 |

|

California |

$17,956,353 |

$5,826,882 |

$23,783,235 |

$17,011,836 |

$5,556,457 |

$22,568,293 |

|

Colorado |

$1,830,397 |

$593,968 |

$2,424,365 |

$1,715,070 |

$560,182 |

$2,275,252 |

|

Connecticut |

$1,287,002 |

$417,635 |

$1,704,637 |

$1,187,543 |

$387,879 |

$1,575,422 |

|

Delaware |

$500,000 |

$65,175 |

$565,175 |

$500,000 |

$67,690 |

$567,690 |

|

District of Columbia |

$1,091,992 |

$100,688 |

$1,192,680 |

$1,091,992 |

$93,992 |

$1,185,984 |

|

Florida |

$6,234,797 |

$2,023,207 |

$8,258,004 |

$6,795,860 |

$2,219,685 |

$9,015,545 |

|

Georgia |

$2,848,232 |

$924,258 |

$3,772,490 |

$3,322,872 |

$1,085,327 |

$4,408,199 |

|

Hawaii |

$500,000 |

$125,321 |

$625,321 |

$500,000 |

$134,984 |

$634,984 |

|

Idaho |

$500,000 |

$123,987 |

$623,987 |

$500,000 |

$134,090 |

$634,090 |

|

Illinois |

$5,421,287 |

$1,759,221 |

$7,180,508 |

$5,060,733 |

$1,652,953 |

$6,713,686 |

|

Indiana |

$4,571,089 |

$1,483,329 |

$6,054,418 |

$5,172,863 |

$1,689,577 |

$6,862,440 |

|

Iowa |

$1,890,809 |

$613,572 |

$2,504,381 |

$1,798,332 |

$587,377 |

$2,385,709 |

|

Kansas |

$2,120,818 |

$688,210 |

$2,809,028 |

$2,179,305 |

$711,811 |

$2,891,116 |

|

Kentucky |

$2,374,107 |

$770,403 |

$3,144,510 |

$2,290,609 |

$748,166 |

$3,038,775 |

|

Louisiana |

$1,369,239 |

$444,321 |

$1,813,560 |

$1,381,111 |

$451,103 |

$1,832,214 |

|

Maine |

$589,574 |

$191,318 |

$780,892 |

$569,158 |

$185,900 |

$755,058 |

|

Maryland |

$1,275,300 |

$413,838 |

$1,689,138 |

$1,238,095 |

$388,475 |

$1,626,570 |

|

Massachusetts |

$3,143,968 |

$1,020,225 |

$4,164,193 |

$3,125,354 |

$1,020,813 |

$4,146,167 |

|

Michigan |

$4,254,794 |

$1,380,691 |

$5,635,485 |

$4,171,796 |

$1,215,646 |

$5,387,442 |

|

Minnesota |

$2,000,246 |

$649,085 |

$2,649,331 |

$2,312,489 |

$755,312 |

$3,067,801 |

|

Mississippi |

$1,385,370 |

$449,556 |

$1,834,926 |

$1,450,395 |

$473,733 |

$1,924,128 |

|

Missouri |

$3,743,029 |

$1,214,622 |

$4,957,651 |

$3,695,120 |

$1,206,912 |

$4,902,032 |

|

Montana |

$741,710 |

$240,687 |

$982,397 |

$852,977 |

$278,602 |

$1,131,579 |

|

Nebraska |

$1,209,016 |

$392,329 |

$1,601,345 |

$1,168,877 |

$381,783 |

$1,550,660 |

|

Nevada |

$1,436,926 |

$466,286 |

$1,903,212 |

$1,362,879 |

$445,148 |

$1,808,027 |

|

New Hampshire |

$500,000 |

$90,835 |

$590,835 |

$500,000 |

$99,650 |

$599,650 |

|

New Jersey |

$2,297,848 |

$732,632 |

$3,030,480 |

$2,297,848 |

$682,262 |

$2,980,110 |

|

New Mexico |

$748,353 |

$242,842 |

$991,195 |

$750,875 |

$245,253 |

$996,128 |

|

New York |

$11,585,958 |

$2,301,357 |

$13,887,315 |

$11,585,958 |

$2,076,464 |

$13,662,422 |

|

North Carolina |

$3,118,348 |

$1,011,911 |

$4,130,259 |

$3,137,205 |

$1,024,684 |

$4,161,889 |

|

North Dakota |

$500,000 |

$140,101 |

$640,101 |

$500,000 |

$134,884 |

$634,884 |

|

Ohio |

$3,959,690 |

$1,284,929 |

$5,244,619 |

$4,012,668 |

$1,310,631 |

$5,323,299 |

|

Oklahoma |

$3,625,684 |

$1,176,543 |

$4,802,227 |

$3,395,195 |

$1,108,949 |

$4,504,144 |

|

Oregon |

$2,323,888 |

$754,107 |

$3,077,995 |

$2,196,261 |

$717,349 |

$2,913,610 |

|

Pennsylvania |

$4,693,810 |

$1,523,153 |

$6,216,963 |

$4,876,889 |

$1,592,905 |

$6,469,794 |

|

Puerto Rico |

$1,169,025 |

$379,351 |

$1,548,376 |

$1,273,236 |

$415,868 |

$1,689,104 |

|

Rhode Island |

$579,452 |

$188,033 |

$767,485 |

$554,875 |

$181,235 |

$736,110 |

|

South Carolina |

$1,094,694 |

$355,231 |

$1,449,925 |

$1,132,238 |

$369,815 |

$1,502,053 |

|

South Dakota |

$500,000 |

$120,497 |

$620,497 |

$500,000 |

$127,043 |

$627,043 |

|

Tennessee |

$2,406,052 |

$780,770 |

$3,186,822 |

$2,364,147 |

$772,185 |

$3,136,332 |

|

Texas |

$9,602,069 |

$3,115,894 |

$12,717,963 |

$9,113,209 |

$2,976,585 |

$12,089,794 |

|

Utah |

$936,232 |

$303,809 |

$1,240,041 |

$821,678 |

$268,379 |

$1,090,057 |

|

Vermont |

$500,000 |

$115,263 |

$615,263 |

$500,000 |

$132,204 |

$632,204 |

|

Virginia |

$1,454,006 |

$471,828 |

$1,925,834 |

$1,438,848 |

$469,961 |

$1,908,809 |

|

Washington |

$3,347,416 |

$1,086,244 |

$4,433,660 |

$3,224,946 |

$1,053,342 |

$4,278,288 |

|

West Virginia |

$1,441,038 |

$467,620 |

$1,908,658 |

$1,506,916 |

$492,194 |

$1,999,110 |

|

Wisconsin |

$2,188,125 |

$710,052 |

$2,898,177 |

$2,154,777 |

$703,800 |

$2,858,577 |

|

Wyoming |

$500,000 |

$101,099 |

$601,099 |

$500,000 |

$107,391 |

$607,391 |

|

Total for States |

$137,823,803 |

$42,583,418 |

$180,407,221 |

$137,813,258 |

$42,442,844 |

$180,256,102 |

|

Tribal Entities |

||||||

|

KS Prairie Band of Potawatomi |

$17,966 |

$5,830 |

$23,796 |

$15,584 |

$5,090 |

$20,674 |

|

NE Santee Sioux Nation |

$12,829 |

$4,163 |

$16,992 |

12,284 |

4,012 |

$16,296 |

|

OR Confederated Tribe of Warm Springs |

$30,608 |

$9,933 |

$40,541 |

42,994 |

14,043 |

$57,037 |

|

WA Port Gamble S'Klallam Tribe |

$14,794 |

$4,801 |

$19,595 |

15,880 |

5,187 |

$21,067 |

|

Total for Tribal Entities |

$76,197 |

$24,727 |

$100,924 |

$86,742 |

28,332 |

$115,074 |

|

Total for States and Tribal Entities |

$137,900,000 |

42,608,145 |

$180,508,145 |

$137,900,000 |

42,471,176 |

$180,371,176 |

Source: Congressional Research Service, based on correspondence with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration on Children Youth and Families, Administration for Children, Children's Bureau, August 2017.

Notes: The Fostering Connections to Success and Increasing Adoptions Act (P.L. 110-351) permits, as of FY2010, an Indian tribe, tribal organization, or tribal consortium that receives direct funding from HHS to provide child welfare services or enters into a cooperative agreement or contract with the state to provide foster care to apply for and receive an allotment of CFCIP and ETV funds directly from HHS. To be eligible, a tribal entity must be receiving Title IV-E funds to operate a foster care program (under a Title IV-E plan approved by HHS or via a cooperative agreement or contract with the state).

Appendix C. Funding Returned to the Treasury for the Chafee Foster Care Independence Program (CFCIP) and Education and Training Voucher (ETV) Program

Table C-1. Chafee Foster Care Independence Program (CFCIP) and Education and Training Voucher (ETV) Program Funds Returned By States to the Treasury, FY2006-FY2014

Funding in nominal dollars; "jurisdiction" refers to each of the 50 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and tribal entities

|

FY2007 |

FY2008 |

FY2009 |

FY2010 |

FY2011 |

FY2012 |

FY2013 |

FY2014 |

|

|

Total amount and share of CFCIP funds awarded to jurisdictions that were returned |

$230,136 |

$352,337 |

$662,419 |

$1,635,560 |