Introduction

Thousands of oil and chemical spills of varying size and magnitude occur in the United States each year. When a spill occurs, state and local officials located in proximity to the incident generally are the first responders and may elevate an incident for federal attention if greater resources are desired.

The National Oil and Hazardous Substances Pollution Contingency Plan—often referred to as the National Contingency Plan (NCP) for short—establishes the procedures for the federal response to oil and chemical spills. The scope of the NCP specifically encompasses discharges of oil into or upon U.S. waters and adjoining shorelines and releases of hazardous substances into the environment more broadly. Several hundred toxic chemicals and radionuclides are designated as hazardous substances under the NCP, and other pollutants and contaminants also fall within the scope of its response authorities. The NCP is codified in federal regulation and is authorized in multiple federal statutes. Unlike most other federal emergency response plans that are administrative mechanisms, the regulations of the NCP have the force of law and are binding and enforceable.

After observing the effects of the 1967 Torrey Canyon oil tanker spill off the coast of England,1 the Johnson Administration developed the initial version of the NCP in 1968. The first NCP was an administrative initiative to coordinate the federal response to potential oil spills in U.S. waters. Congress later enacted the Federal Water Pollution Control Act Amendments of 19722 (often referred to as the Clean Water Act) to provide explicit statutory authority for the federal response to discharges of oil or hazardous substances into or upon U.S. waters within the contiguous zone and the adjoining shorelines.3 The 1972 amendments also explicitly directed the preparation of the NCP to carry out these authorities.

The NCP has been revised multiple times since 1968 to implement additional federal statutory authorities that Congress has enacted in the wake of other major incidents. The discovery of severely contaminated sites in the 1970s, such as Love Canal in New York, led to the enactment of the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980 (CERCLA).4 This statute addresses releases of hazardous substances, pollutants, and contaminants into the environment, and it directed a federal response plan for these incidents to be included in the NCP. Although Congress initially considered including oil spills within the response authorities of CERCLA, petroleum was excluded from the scope of the statute with the intention of addressing oil spills in separate legislation.

The 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill in Alaska led to the enactment of the Oil Pollution Act of 1990 (OPA).5 This statute clarified and expanded the oil spill response authorities of the Clean Water Act extending to U.S. waters within the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ)6 and directed revisions to the NCP to carry out these authorities.

Over time, the NCP has been applied on a routine basis to respond to many varied incidents across the United States involving discharges of oil and releases of hazardous substances. The framework and procedures of the NCP often generate interest among Members of Congress and affected stakeholders in the execution of federal resources to respond to an incident and the participation of state, local, and private entities. Whereas individual incidents may differ in terms of the magnitude, scope, complexity, and associated hazards, effective coordination of the respondents and the adequacy of resources available to carry out a response can be common issues. Larger and more complex spills may garner more prominent attention, such as the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. Some raised questions about the authorities and roles of the entities involved in the response to that incident, including federal agencies, state and local governments, and private parties.7

This report provides background information on the NCP to address potential questions that may arise in congressional oversight of the federal response to particular incidents. The report discusses the federal statutes that authorize the NCP and related executive orders; mechanisms for reporting incidents to the federal government; the framework under which federal, state, and local roles are to be coordinated; funding mechanisms for federal response actions, including liability for response costs and related damages; and circumstances under which the NCP may be integrated within the National Response Framework (NRF) to address multifaceted incidents, such as major disasters or emergencies. The Appendix to this report provides a chronology of the development of the NCP over time. A list of commonly used acronyms also is provided below.

|

ACP |

Area Contingency Plan |

|

ATSDR |

Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry |

|

CDC |

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

|

CERCLA |

Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act |

|

CWA |

Clean Water Act |

|

DHS |

Department of Homeland Security |

|

EPA |

Environmental Protection Agency |

|

HHS |

Department of Health and Human Services |

|

NCP |

National Contingency Plan (short for National Oil and Hazardous Substances Pollution Contingency Plan) |

|

NPL |

National Priorities List |

|

NRF |

National Response Framework |

|

NRT |

National Response Team |

|

OPA |

Oil Pollution Act |

|

OSC |

On-Scene Coordinator |

|

RRT |

Regional Response Team |

|

SARA |

Superfund Amendments and Reauthorization Act of 1986 |

Statutory Response Authorities

Since its inception in 1968, the NCP has been revised on multiple occasions to establish regulatory procedures for implementing the federal statutory authorities that Congress has expanded over time to respond to incidents involving a discharge of oil or a release of a hazardous substance. These statutes are outlined briefly below in chronological order of enactment. For a discussion of funding authorized under these statutes to carry out response actions and the scope of liability for response costs and related damages, see the section on "Funding and Liability" later in this report.

The 1972 amendments to the Clean Water Act added Section 311 to the statute to provide explicit statutory authority for the President to respond to a discharge of oil or a hazardous substance into or upon the navigable waters of the United States and adjoining shorelines, and the waters of the contiguous zone.8 The original NCP had focused on the federal response to oil spills. Section 311 directed the President to further develop the NCP to govern discharges of both oil and hazardous substances within the above aspects of the natural environment. The statute also required several basic elements to be included in the NCP, including mechanisms to coordinate the federal, state, and local roles in responding to an incident, and specific response procedures.

The Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA) of 1980 established the Superfund program and expanded the authorities of the President to respond to releases of hazardous substances into the environment more broadly than Section 311 of the Clean Water Act.9 Section 101(8) of CERCLA explicitly defines the term "environment" to include "the navigable waters, the waters of the contiguous zone, and the ocean waters of which the natural resources are under the exclusive management authority of the United States under the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act," and any other surface water, groundwater, surface soil, sub-surface soil, or ambient air within or under the jurisdiction of the United States.10 CERCLA also expanded federal response authority to address releases of pollutants and contaminants into the environment that may present an imminent and substantial danger to the public health or welfare. Section 105 of CERCLA directed the President to revise the NCP to include a plan for responding to these types of incidents.11 This plan is codified in Subpart E of the regulations of the NCP.12

The Superfund Amendments and Reauthorization Act of 1986 (SARA)13 amended various response, liability, and enforcement provisions of CERCLA. Among these provisions, SARA amended Section 105 of the statute directing the President to further revise the NCP and expand the criteria used to evaluate contaminated sites for placement on the National Priorities List (NPL). The primary purpose of the NPL is to identify—in conjunction with the states—the most threatening sites that warrant federal involvement in long-term remediation. Sites that may require short-term response actions to address emergency situations do not require listing on the NPL to be eligible for federal involvement under the NCP.

The Oil Pollution Act of 1990 expanded and clarified the President's authorities under Section 311 of the Clean Water Act specifically to respond to discharges of oil into or upon the navigable waters of the United States and adjoining shorelines, the waters of the EEZ, or that may affect natural resources belonging to, appertaining to, or under the exclusive management authority of the United States.14 As amended by OPA, Section 311(d) of the Clean Water Act directed the President to further revise the NCP to develop specific procedures for implementing these oil spill response authorities.15 The procedures are codified in Subpart D of the regulations of the NCP and provide the federal plan for undertaking an oil spill response.

Executive Orders

Several executive orders have delegated the President's response authorities under the above statutes to the federal departments and agencies tasked with implementing the NCP. The two executive orders discussed below amended previous executive orders that initially had delegated the President's response authorities after the enactment of the amendments to the Clean Water Act in 1972 and the enactment of CERCLA in 1980.

- Executive Order 12580 was issued in 1987 and delegated the President's authorities to respond to releases of hazardous substances, pollutants, and contaminants under CERCLA, as amended in 1986 by SARA.16

- Executive Order 12777 was issued in 1991 and delegated the President's authorities to respond to discharges of oil under Section 311 of the Clean Water Act, as amended in 1990 by OPA.17

Under both executive orders, the coordination of the federal response generally is delegated to EPA within the inland zone and to the U.S. Coast Guard within the coastal zone, unless the two agencies agree otherwise.18 For the purpose of these delegated roles, the coastal zone is defined in the NCP to include "all U.S. waters subject to the tide, United States waters of the Great Lakes, specified ports and harbors on inland rivers, waters of the contiguous zone, other waters of the high seas subject to the NCP, and the land surface or land substrata, ground waters, and ambient air proximal to those waters."19

Conversely, the NCP defines the inland zone to encompass "the environment inland of the coastal zone excluding the Great Lakes and specified ports and harbors on inland rivers."20

Although responsibility for coordinating a federal response generally is divided between EPA and the U.S. Coast Guard with respect to these two geographic zones, both executive orders assign EPA the sole responsibility of revising the regulations of the NCP, as warranted. Prior to proposing any revisions to the NCP for public comment, EPA must consult with the U.S. Coast Guard and other federal departments and agencies that serve as standing members of the National Response Team (discussed below). As generally is the case with any federal regulation, revisions to the NCP also are subject to the federal rulemaking process, including the opportunity for public comment. Both executive orders further specify that any proposed or finalized revisions to the NCP would be subject to review and approval by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB).

Executive Order 12580 established differing lead agency roles in responding to releases of hazardous substances at federal facilities and vessels. The Department of Defense (DOD) and Department of Energy (DOE) administer most of the federal facilities from which a release of a hazardous substance has occurred.21 Executive Order 12580 explicitly delegates the President's response authorities under CERCLA to DOD and DOE at facilities and vessels within their respective jurisdiction, custody, or control. DOD also is responsible for responding to incidents involving the removal of military weapons and munitions that are or were under its jurisdiction, custody, or control. Other federal departments and agencies may lead the federal response under CERCLA at facilities and vessels under their jurisdiction, custody, or control only in nonemergency situations. Within their respective zones, EPA or the U.S. Coast Guard would retain the lead role under CERCLA in emergency situations at these federal facilities and vessels.

Executive Order 12777 did not similarly delegate the President's oil spill response authorities under Section 311 of the Clean Water Act with respect to federal facilities and vessels. Under the NCP, the U.S. Coast Guard retains the lead role in responding to discharges of oil from federal facilities or vessels within the coastal zone, regardless of which other federal department or agency may have jurisdiction, custody, or control over that facility or vessel. EPA similarly would lead the response to such incidents at federal facilities in the inland zone. In practice, the federal department or agency that administers the facility or vessel still may carry out a response with its own funds, under the direction of the U.S. Coast Guard or EPA within their respective zones.

The NCP itself also establishes the lead roles of federal departments and agencies in accordance with the delegation of the President's authorities under these two executive orders.22

Reporting an Incident

A federal response to a discharge of oil or a release of a hazardous substance may be triggered upon reporting of the incident. The National Response Center serves as the national clearinghouse of all discharges of oil and releases of hazardous substances in the United States that are reported to the federal government.23 The U.S. Coast Guard is responsible for administering the National Response Center, collecting data on reported incidents, and notifying the appropriate federal departments and agencies that may be involved in responding to an incident under the NCP in coordination with state and local authorities. The U.S. Coast Guard itself generally would be responsible for coordinating a federal response within the coastal zone, but would notify EPA to coordinate the federal response within the inland zone.

The parties who discharge oil or release a hazardous substance are required to report the incident to the National Response Center if the quantity of the discharge or release exceeds allowable amounts.24 Reportable discharges of oil include discharges that would (1) violate applicable water quality standards, (2) cause a film or sheen upon or discoloration of the surface of the water or adjoining shorelines, or (3) cause a sludge or emulsion to be deposited beneath the surface of the water or upon adjoining shorelines.25 Reportable quantities of hazardous substances vary by individual substance in pounds (and kilograms), and in curies (and becquerels) for individual radionuclides designated as hazardous substances.26 State or local officials, or members of the public, who witness a discharge or release also may report the incident. Furthermore, state or local officials acting as the first responders on-site may contact the National Response Center to elevate a site for federal attention.

Once the National Response Center is notified of an incident, a federal response may be undertaken in accordance with the framework and procedures of the NCP to draw upon available resources to respond to potential hazards, discussed next.

Coordination of the Federal Response

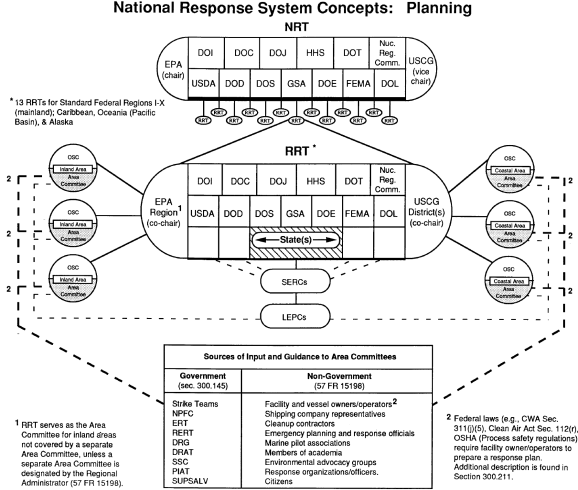

The NCP established the National Response System (NRS) as a multi-tiered framework for coordinating the federal response to a discharge of oil or a release of a hazardous substance, pollutant, or contaminant. The NRS establishes the respective roles of federal, state, and local governments in carrying out a federal response, including the party or parties responsible for the incident and other private entities that may wish to contribute resources. As stated in the NCP, the NRS is intended to be "capable of expanding or contracting to accommodate the response effort required by the size or complexity of the discharge or release."27 Accordingly, the array of respondents and resources used to carry out a response may vary with the magnitude, scope, and complexity of an incident and the associated hazards. The following sections discuss the various components of the NRS, illustrated in Figure 1 as excerpted from the NCP.

|

|

Source: National Oil and Hazardous Substances Pollution Contingency Plan, 40 C.F.R. Part 300, Subpart B—Responsibility and Organization for Response, Section 300.105—General Organization Concepts. Notes: NRT = National Response Team, RRT = Regional Response Team, OSC = On-Scene Coordinator, SERC = State Emergency Response Commission, LEPC = Local Emergency Response Commission. Federal Departments and Agencies: EPA = Environmental Protection Agency, USCG = U.S. Coast Guard, DOI = Department of the Interior, DOC = Department of Commerce, DOJ = Department of Justice, HHS = Department of Health and Human Services, DOT = Department of Transportation, Nuc. Reg. Comm. = Nuclear Regulatory Commission, USDA = U.S. Department of Agriculture, DOD = Department of Defense, DOS = Department of State, GSA = General Services Administration, DOE = Department of Energy, FEMA = Federal Emergency Management Agency, and DOL = Department of Labor. Strike Teams (i.e. specialized teams): NPFC = National Pollution Funds Center, ERT = (EPA) Environmental Response Team, RERT = (EPA) Radiological Emergency Response Team, DRG = (U.S. Coast Guard) District Response Group, DRAT = (U.S. Coast Guard) District Response Advisory Team, SSC = Scientific Support Coordinator, PIAT = Public Information Assist Team, SUPSALV = (U.S. Navy) Supervisor of Salvage. |

National Response Team

The National Response Team (NRT) consists of 15 federal departments and agencies (Figure 1 ). The specific role of each department and agency in responding to a discharge of oil or a release of a hazardous substance is outlined in the NCP.28 These departments and agencies include

- Environmental Protection Agency (Chair),

- U.S. Coast Guard (Vice-Chair),

- Department of Agriculture,

- Department of Commerce,

- Department of Defense,

- Department of Energy,

- Department of Health and Human Services,

- Department of the Interior,

- Department of Justice,

- Department of Labor

- Department of State,

- Department of Transportation,

- Federal Emergency Management Agency,

- General Services Administration, and

- Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

EPA serves as the "standing" Chair of the NRT, and the U.S. Coast Guard serves as the standing Vice-Chair. Consistent with the delegation of the President's response authorities by executive order, the U.S. Coast Guard becomes the "acting" Chair of the NRT for a federal response to a discharge of oil or a release of a hazardous substance within the coastal zone, and EPA becomes the acting Vice-Chair in such instances.29 Conversely, EPA remains the Chair for a federal response within the inland zone, and the U.S. Coast Guard the Vice-Chair.

Due to the nature of their ongoing missions, the NRT departments and agencies employ skilled personnel and maintain specialized equipment that can enhance the effectiveness of the federal response. For example, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) maintains expertise that may be drawn upon to assess threats to public health resulting from an incident.30 Within HHS, the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) specifically is responsible for assessing public health threats from the release of a hazardous substance, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) assesses public health threats from discharges of oil. The CDC played a prominent role in assessing threats to public health from the oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico in connection with the Deepwater Horizon incident.31

Federal departments and agencies that administer federal facilities and vessels are standing members of the NRT to carry out the response to hazardous incidents that may occur in connection with their own activities. Under the NCP, these departments and agencies also may be called upon to use these capabilities in support of the response to nonfederal incidents that present similar challenges. For example, the U.S. Navy Supervisor of Salvage maintains specialized equipment and capabilities to respond to pollution incidents involving U.S. Naval vessels. These capabilities may be drawn upon to respond to a civilian incident in ocean environments.32 During the Deepwater Horizon incident, for example, the Navy dispatched oil collection equipment to aid in the federal response under the NCP.

In addition, the Department of Justice also serves as a standing member of the NRT to represent the United States in any litigation that may involve the federal response to a discharge of oil or a release of a hazardous substance under the NCP.33

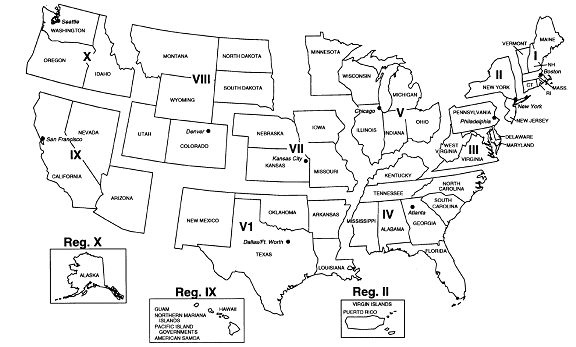

State and Local Involvement in Regional Response Teams

The NCP provides state, territorial,34 local, and tribal governments the opportunity to participate in the federal response to an incident through the Regional Response Teams that fall under the NRT (Figure 1).35 The NCP established 13 Regional Response Teams.36 (See Figure 2 for a map of these regions, as excerpted from the NCP.) Each federal department or agency that is a standing member of the NRT designates an official to serve on each Regional Response Team (RRT) to represent the federal government. The governor of each state or territory within a region may designate an official to represent the state or territorial government. The state and territorial officials serving on a RRT may invite local governments to participate. Indian tribes within a region may designate an official to represent the tribal government.

Because state, territorial, or local officials are likely to be located in closer proximity to incidents that occur within their respective geographic regions, the NCP specifies that they are expected to be the first government representatives on the RRT to arrive at the scene of a discharge or release to take initial response actions.37 Consequently, state, territorial, or local officials usually are the first responders who may initiate immediate safety measures to protect the public. For example, the NCP indicates that state, territorial, or local officials may be responsible for conducting evacuations of affected populations according to applicable state, territorial, or local procedures. As discussed earlier, state, territorial, or local officials acting as the first responders also may notify the National Response Center to elevate an incident for federal involvement, at which point the coordinating framework of the NCP would be applied.

Enacted in 1986, the Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act (EPCRA)38 required each state to create a State Emergency Response Commission (SERC), designate emergency planning districts, and establish Local Emergency Planning Committees (LEPCs) for each district. Each LEPC must prepare a local emergency response plan for the emergency planning district. These local emergency plans are integrated into the appropriate geographic-specific area response plan that may cover several local planning districts,39 discussed in the "Area Committees" section of this report below.

Area Committees

Area Committees support the Regional Response Teams in preparing for a response to a discharge of oil or a hazardous substance into U.S. waters and the adjoining shorelines, as authorized under Section 311(j)(4) of the Clean Water Act (Figure 1).40 The President may designate "qualified" personnel from federal, state, territorial, and local agencies to serve on these committees. The primary function of each committee is to prepare an Area Contingency Plan (ACP) for its designated geographic area within a region. The geographic-specific aspects of an ACP augment the more general provisions of the NCP. When implemented together, these plans are intended to ensure an effective response to a discharge from a vessel, offshore facility, or onshore facility operating in or near the area. CERCLA does not explicitly authorize Area Committees with respect to a release of a hazardous substance into the environment, whereas Section 311 of the Clean Water Act does authorize such committees to cover discharges of hazardous substances into U.S. waters and the adjoining shorelines. In inland areas not covered by the Clean Water Act, the Regional Response Teams may fulfill the planning functions of the Area Committees.

On-Scene Coordinator

Considering the potentially large number of individuals who may be involved in the federal response to an incident under the NCP, one high-level federal official is responsible for directing and coordinating all of the on-the-ground actions at the scene of a discharge of oil or a release of a hazardous substance. A pre-designated On-Scene Coordinator (OSC) for the geographic area where the discharge or release occurs performs this lead role.41 Within their respective locales, the OSCs also oversee the development of ACPs by the Area Committees to ensure consistency with the regulatory procedures of the NCP.

EPA generally is responsible for designating the OSCs for incidents involving a discharge of oil or a release of a hazardous substance that may occur in the inland zone, and the U.S. Coast Guard in the coastal zone.42 U.S. Coast Guard Captains of the Port usually serve as the OSCs, coordinating the response to discharges of oil from all facilities and vessels operating within the coastal zone. The NCP established these lead agency roles in accordance with the executive orders that delegated the President's response authorities, including exceptions for responses to incidents at federal facilities at which the federal department or agency that administers the facility may serve as the OSC instead. See the section of this report on "Executive Orders."

The OSC is responsible for making final decisions on what specific actions are necessary to carry out the federal response to an incident, the use and allocation of federal funds to carry out those actions, what other federal resources may be needed to carry out those actions, and what specific responsibilities are delegated to each entity participating in the federal response, including the party or parties responsible for the incident. The OSC also determines when the federal response to an individual incident is complete and the regulations of the NCP are satisfied. While state, territorial, or local officials may participate in a federal response under the direction of the OSC, the NCP does not preclude states, territories, or local governments from carrying out response actions under their own authorities.

Potential Role of Secretary of Homeland Security

Although EPA and the U.S. Coast Guard usually serve as the OSCs within their respective geographic zones, the Secretary of Homeland Security may assume the lead role in directing a response taken under the NCP in certain circumstances. First, the Secretary of Homeland Security generally has the discretion to assert a lead role in the coastal zone in the capacity of administering the functions of the U.S. Coast Guard within the Department of Homeland Security.43 Second, Homeland Security Presidential Directive 5 (issued in 2003) more broadly authorizes the Secretary of Homeland Security to be the "principal federal official for domestic incident management" in response to terrorist attacks, major disasters, or other emergencies in any of the following situations:

- a federal department or agency acting under its own authority has requested the assistance of the Secretary;

- the resources of state and local authorities are overwhelmed and federal assistance has been requested by the appropriate state and local authorities;

- more than one federal department or agency has become substantially involved in responding to the incident; or

- the President has directed the Secretary to assume responsibility for managing the domestic incident.44

In any of these instances, the procedures and requirements of the NCP still would continue to apply, as the directive is an administrative mechanism that does not preempt existing authorities.45

In practice, the Secretary of Homeland Security has not been directly involved on a routine basis in leading response actions taken under the NCP. The lead role of the Secretary generally has been reserved for incidents of greater magnitude, scope, and complexity. For example, Secretary Napolitano coordinated the response taken under the NCP during the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. The Secretary's potential role in coordinating a response to other incidents under the NCP generally would depend on the nature of the incident and the need for elevating coordination within the executive branch in the types of situations identified above.

Oil Spills of National Significance

The NCP establishes differing roles with respect to the OSC for an oil spill of national significance (SONS).46 The NCP does not provide a similar counterpart for releases of hazardous substances.47 The Administrator of EPA is responsible for designating a SONS in the inland zone, and the Commandant of the U.S. Coast Guard is responsible for making such designations in the coastal zone. For a SONS in the inland zone, the Administrator of EPA may appoint a senior agency official to assist the OSC in "communicating with affected parties and the public and coordinating federal, state, local, and international resources at the national level."48 For a SONS in the coastal zone, the Commandant of the U.S. Coast Guard may appoint a National Incident Commander (NIC) to assume the role of the OSC in these capacities, rather than merely assist the OSC. Although the designation of a SONS may affect communication and coordination roles, it does not alter the oil response procedures or requirements of the NCP, and does not make any additional funds available to carry out a response.

In practice, the designation of a discharge of oil as a SONS is rare. On April 29, 2010, Secretary Napolitano classified the Deepwater Horizon event as a SONS and appointed U.S. Coast Guard Admiral Thad Allen as the NIC for that incident. This was the first spill to receive such a designation.

Nongovernmental Participation

The participation of nongovernmental entities in a federal response may include parties responsible for a discharge of oil or a release of a hazardous substance who perform response actions under the direction of the OSC, private contractors procured either by a responsible party or a federal agency to conduct the physical work, and members of the general public who may wish to contribute resources.49 In particular, Section 311(j)(5)(D) of the Clean Water Act requires certain types of facilities and vessels to prepare response plans that would ensure the availability of private personnel and equipment to address a worst case discharge of oil or a hazardous substance into or upon navigable waters of the United States, adjoining shorelines, and the Exclusive Economic Zone.50 These facility and vessel plans must be consistent with the applicable ACPs. In many instances, private facilities and vessels may maintain a contractual relationship with an oil spill removal organization to satisfy this planning requirement for potential oil spills.

The NCP also encourages industry groups, academic organizations, and others to commit resources for federal response operations.51 Commitments of nongovernmental entities may be identified in ACPs, which can be called upon when an incident occurs. Nongovernmental entities also may generate scientific or technical information to assist in the development of response strategies, which can be incorporated into ACPs. Individual volunteers also may participate in the federal response. The NCP requires Area Committees to establish procedures that allow for "well organized, worthwhile, and safe use of volunteers."52 However, the participation of volunteers in the response to a specific incident may be limited to certain activities more appropriate for their skill level or could be restricted if dangerous conditions exist.

Funding and Liability

Congress has established two dedicated trust funds to finance the costs of a federal response to a discharge or oil or release of a hazardous substance, pollutant, or contaminant. Through its National Pollution Funds Center, the U.S. Coast Guard administers the Oil Spill Liability Trust Fund to finance the costs of responding to a discharge of oil.53 Currently, revenues for the Oil Spill Liability Trust Fund primarily are derived from a dedicated nine cents per-barrel tax on domestic and imported oil. The tax is scheduled to terminate at the end of 2017.

EPA administers the Hazardous Substance Superfund Trust Fund to finance the costs of responding to a release of a hazardous substance, pollutant, or contaminant.54 The Superfund Trust Fund is financed mostly with revenues transferred from the General Fund of the U.S. Treasury, since the taxes on domestic and imported oil, chemical feedstocks, and corporate income that once financed this trust fund expired at the end of 1995. Neither of these trust funds is available to cover the costs of responding to a discharge of oil or a release of a hazardous substance from a federal facility or vessel. Congress appropriates separate funding directly to the federal departments or agencies with jurisdiction, custody, or control over the facility or vessel from which the discharge or release occurred to pay the response costs of the federal government.

These two trust funds differ in terms of how the monies are made available to carry out a response. Monies from the Oil Spill Liability Trust Fund are authorized as mandatory (i.e., permanent) appropriations that do not require a subsequent discretionary appropriation before they are made available to federal agencies for obligation. However, these monies are subject to certain caps on annual withdrawals from the trust fund55 and total expenditures per incident.56 Monies from the Superfund Trust Fund are subject to discretionary appropriations before they are made available for response actions. To enable response capabilities, Congress has annually appropriated monies out of this trust fund to EPA's Superfund account and has reserved separate portions of these funds for emergency "removal" actions versus long-term "remedial" actions. These funds remain available indefinitely until they are expended.

The federal government may recover its response costs from the responsible parties under the liability provisions of OPA and CERCLA, respectively. Recovered funds are to be deposited back into the respective trust fund that financed the federal response.57 The responsible parties also may perform and pay for response actions up-front with their own monies, subject to direction by the OSC. In the event that the responsible parties are not financially viable or cannot be identified, the applicable trust fund still may pay for federal response actions, up to the amounts made available from that trust fund and within certain limitations.

Financial liability differs somewhat for discharges of oil versus releases of hazardous substances. Section 1002 of OPA establishes the liability of parties responsible for a discharge of oil, including response costs, natural resource damages, certain categories of economic damages, and damages for net costs borne by states and local governments in providing public services in support of a response.58 Section 107 of CERCLA establishes the liability of parties responsible for a release of a hazardous substance, including response costs, natural resource damages, and the costs of federal public health studies performed by the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry.59 Unlike OPA, CERCLA does not establish a separate category of liability for economic damages, with the exception of certain economic losses that may be compensable through natural resource damages based on the loss of the use of resources.60 Other economic damages attributed to releases of hazardous substances primarily are left to tort law. Notably, CERCLA also does not apply liability to a release of a pollutant or contaminant. The federal government still may respond to such incidents, albeit without a mechanism to recover the costs under CERCLA.

For a presidential declaration of an incident as a major disaster or emergency, funds provided under the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act (the Stafford Act) may finance the federal response costs,61 rather than the above trust funds. The use of Stafford Act funds usually would entail the Secretary of Homeland Security applying the NCP under the National Response Framework (discussed below) to address a discharge of oil or a release of a hazardous substance associated with a major disaster or emergency. In practice, the use of Stafford Act funds to pay for the federal response to a discharge of oil or a release of a hazardous substance has been more limited to discharges or releases caused by natural disasters or other emergencies for which there is not a responsible party to pursue. In such instances, the President may make a Stafford Act declaration to provide federal assistance to augment state and local resources, in the absence of viable responsible parties to pay for the response.62

National Response Framework

The National Response Framework (NRF) is the federal government's broader administrative mechanism that is intended to coordinate the array of federal response plans.63 As such, the NRF provides the administrative policies and guiding principles for a unified response from all levels of government, and all sectors of communities, to all types of hazards through the combined scope of the various federal response plans that it incorporates. However, the NRF itself is not an operational plan that dictates a step-by-step process for responding to a specific type of hazard, nor is the NRF codified in federal regulation like the NCP.64

Through Emergency Support Function (ESF) #10 of the NRF, the Secretary of Homeland Security may apply the operational elements of the NCP for incidents involving the discharge of oil or release of hazardous materials that require a coordinated federal response.65 (ESF #10 references the term hazardous materials and defines that term to include hazardous substances, pollutants, and contaminants covered under the NCP.) Situations in which the application of the NCP through the NRF may occur include

- a major disaster or emergency declared under the Stafford Act, when state and local authorities are overwhelmed and federal assistance is requested;

- an incident to which a federal agency is responding under its own authority and requests support from other federal agencies to respond to aspects of the incident that involve the discharge of oil or release of hazardous materials; or

- an incident for which the Department of Homeland Secretary determines that it should lead the response because of special circumstances.

In practice, the federal response to a discharge of oil or a release of a hazardous substance is most often executed under the regulations of the NCP alone, rather than through the coordinating structures of the NRF under ESF #10. The Secretary of Homeland Security's application of the NCP through the NRF appears to be less common and more limited to multifaceted incidents of greater magnitude, scope, and complexity that may necessitate the coordination of multiple federal response plans. For example, the Department of Homeland Security has stated that the NCP still was applied to the Deepwater Horizon oil spill as a stand-alone regulatory authority without involvement of other federal response plans under the NRF.66 Regardless of whether the NCP is applied as a stand-alone regulatory authority or through the NRF, the procedures for responding to a discharge of oil or release of a hazardous substance are the same because the NCP remains the operative plan in either instance.

Appendix. Chronology of the NCP

Since its inception in 1968, the NCP has been revised on multiple occasions to develop procedures for implementing the federal statutory authorities that Congress has expanded over time to respond to discharges of oil and releases of hazardous substances, pollutants, and contaminants. Major events in the development of the NCP are outlined below.

- September 1968: Several departments in the Johnson Administration published the National Multi-Agency Oil and Hazardous Materials Pollution Contingency Plan. This version established a Joint Operations Center, a national reaction team, and regional reaction teams. This first version of the NCP was prepared under an administrative initiative, and some have characterized its legal authority as being "not as straightforward" as subsequent versions codified in federal regulation.67

- April 1970: The Water Quality Improvement Act of 1970 (P.L. 91-224) directed the President to publish a National Contingency Plan for the removal of oil. The act included specific details such as task forces at major ports, a national coordination center, and a schedule identifying potential dispersant uses. This act also altered the primary response authority provision, stating that "the President is authorized to act to remove or arrange for the removal of such oil at any time, unless he determines such removal will be done properly by the owner or operator of the vessel, onshore facility, or offshore facility from which the discharge occurs."

- June 1970: Pursuant to P.L. 91-224, the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) published in the Federal Register a National Oil and Hazardous Materials Pollution Contingency Plan.68 This plan established the National Response Center, National Response Team, Regional Response Team, and the On-Scene Commander roles (later termed On-Scene Coordinator).69 The plan addressed discharges of oil and "hazardous polluting substances."

- August 1971: CEQ made several modifications to the NCP. CEQ changed the name of the plan to the one that still exists today—the National Oil and Hazardous Substances Pollution Contingency Plan. The revised plan established roles for the newly created Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.70 In particular, the plan designated EPA as the chair of the National Response Team.71

- October 1972: The Federal Water Pollution Control Act Amendments of 1972 (P.L. 92-500)—often referred to as the Clean Water Act—amended the 1970 statutory authority of the NCP by explicitly requiring it to address hazardous substances as well as oil.72

- August 1973: Executive Order 11735 delegated presidential authorities pursuant to the 1972 amendments to the Clean Water Act to various federal agencies, including EPA, the Secretary of the Department in which the U.S. Coast Guard is operating, and the Council on Environmental Quality.73

- August 1973: CEQ published a revised NCP, pursuant to the 1972 amendments to the Clean Water Act and lessons learned from the National Response Team.74 The NCP was codified in 40 C.F.R. Part 1510.

- February 1975: CEQ issued a revised version of the NCP, based on comments regarding the 1973 NCP.75

- December 1977: The Clean Water Act Amendments of 1977 (P.L. 95-217) required revisions to the NCP to address "imminent threats" of oil and hazardous substance discharges.

- March 1980: CEQ revised the NCP based on the 1977 amendments to the Clean Water Act and experiences with several, high-profile spills at that time.76 The 1980 changes involved, among other things, state participation, local contingency plans, and a national pollution equipment inventory.

- December 1980: The Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980 (CERCLA; P.L. 96-510) required the President to develop, and incorporate into the NCP, procedures for prioritizing and responding to releases of hazardous substances, pollutants, and contaminants into the environment.

- August 1981: Executive Order 12316, among other provisions, delegated to EPA the authority to amend the NCP.77

- July 1982: EPA issued a revised NCP pursuant to CERCLA.78 The existing NCP structure was largely unchanged. EPA added a new subpart in the regulations with authorities and requirements that specifically addressed hazardous substance response activities.

- November 1985: EPA revised the NCP regulations to, among other changes, address "applicable or relevant and appropriate requirements" (ARARs) during response activities.79

- October 1986: The Superfund Amendments and Reauthorization Act of 1986 (SARA; P.L. 99-499) amended various response, liability, and enforcement provisions of CERCLA and directed the President to revise the NCP to carry out these authorities.80 Title III of the act (EPCRA) created SERCs and LEPCs.

- January 1987: Executive Order 12580 delegated various functions assigned to the President in CERCLA, as amended by SARA.81

- March 1990: EPA revised the NCP based on Executive Order 12580 and the amendments to CERCLA in SARA, including changes to hazardous substance reporting and response provisions, federal department and agency roles for federal facilities and vessels, and state and public participation.82

- October 1990: Catalyzed by the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill in Alaskan waters, Congress enacted the Oil Pollution Act of 1990 (OPA; P.L. 101-380).83 Among other provisions, OPA provided authority to the President to perform cleanup immediately using federal resources, monitor the response efforts of the spiller, or direct the spiller's cleanup activities.84 The act also required the President to amend the NCP to establish procedures and standards for responding to worst-case oil spill scenarios.

- October 1991: Executive Order 12777 delegated various functions assigned to the President in OPA.85

- September 1994: EPA revised the NCP based on OPA and its amendments to the Clean Water Act. The modifications to the NCP reflected the revised authorities of the President (delegated to the U.S. Coast Guard or EPA) to direct and/or undertake responses to oil spills. Additions to the NCP also included provisions regarding the National Strike Force Coordination Center, Area Committees, Area Contingency Plans (ACPs), vessel and facility oil spill response planning requirements, and other response elements.