Overview

Since the 114th Congress, the Armed Services Committees have worked to reform the Department of Defense's acquisition processes. This focus continues in each committee's reported version of the FY2018 National Defense Authorization Act (H.R. 2810 and S. 1519).

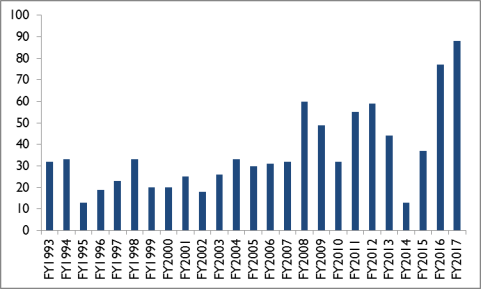

Congress has increased the volume of acquisition reform provisions enacted in recent years. In the FY2017 bill, Congress enacted 88 provisions in Title VIII, "Acquisition Policy, Acquisition Management, and Related Matters" (see Figure 1). That number of provisions was four times greater than the average number of Title VIII provisions in the past 25 years. The FY2017 act itself continued a trend started by the FY2016 enacted bill, which had 77 provisions in Title VIII, the most since the FY2008 act, which had 60 provisions.

|

Figure 1. Number of NDAA Provisions in Title VIII, "Acquisition Policy, Acquisition Management, and Related Matters," Since 1993 |

|

|

Source: CRS analysis of public laws. |

This year's Senate bill includes 66 provisions in Title VIII compared to 85 in FY2017 and 55 in FY2016, as displayed in Table 1. The House bill includes 48 provisions compared to 44 in FY2017 and 58 in FY2016. In the FY2017 bill, the conference report identified 16 provisions of which both chambers' bills had similar versions; CRS has identified 11 similar provisions or directive report language in both FY2018 reported bills.

Table 1. Number of NDAA Provisions in Title VIII, "Acquisition Policy, Acquisition Management, and Related Matters"

|

FY2016 |

FY2017 |

FY2018 |

|

|

Senate bill |

55 |

85 |

66 |

|

House bill |

58 |

44 |

48 |

|

Final NDAA |

77 |

88 |

n/a |

Source: FY2018 NDAA: S. 1519 as placed on Senate Legislative Calendar and H.R. 2810 as passed in the House; FY2017 NDAA: P.L. 114-328, S. 2943 as passed in the Senate on June 14, 2016, H.R. 4909 as passed in the House on May 18, 2016; FY2016 NDAA: P.L. 114-92, H.R. 1735 as passed in the Senate on June 18, 2015 and the House on May 15, 2015.

Note: House bill FY2017 includes 5 provisions from Title XVII, Department of Defense Acquisition Agility.

The bills address several major areas of shared interest:

- commercial items,

- contracts for services,

- intellectual property,

- "other transactions" authority, and

- management of the acquisition system.

The FY2018 House bill builds on a stand-alone acquisition reform bill (H.R. 2511) introduced by the chairman of the House Armed Services Committee in May 2017. Following a model used for FY2017, the stand-alone bill unveiled 15 of 48 provisions included in Title VIII of the House-passed NDAA. All but two of these provisions were revised from the stand-alone bill's text, though several of the revisions include only minor technical or date changes. The House passed H.R. 2810 as amended on July 14, 2017, by a vote of 344-81.

While the Senate Armed Services Committee did not preview its provisions before committee action, it summarized the bill's efforts as continuing "a comprehensive overhaul of the acquisition system to ensure that our men and women in uniform have the equipment they need to succeed and to drive innovation by allocating funds for advanced technology development and next-generation capabilities to ensure America's military dominance."1 The chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee, Senator John McCain, placed the committee-reported bill, S. 1519, on the Senate Legislative Calendar on July 10, 2017.

These shared areas of interest are treated individually below. Both bills include seven provisions with very similar language not included in the major areas, which are discussed separately below.

Select Areas of Interest

Commercial Items

In the last few years, both chambers have focused on the procurement of commercial items.2 The Senate created a new subtitle under Title VIII in its version of the FY2016 NDAA, "Provisions Relating to Commercial Items," which it repeated in its FY2017 and FY2018 bills. The House responded in FY2017 by adding its own commercial items subtitle but it did not include a separate subtitle in FY2018.

Title 10, Section 2377, of the United States Code sets out procedures to prefer the acquisition of commercial items. Generally, commercial items are items sold to the public. However, items that have been modified for government use can still be considered commercial items.3 A separate term—commercially available off-the-shelf—applies to items that have not been modified in any way for government use.4 To encourage the use of commercial items, Section 2375 exempts them from many statutes and regulations that otherwise apply to defense acquisition.5 For example, items may be exempted from the government's right to see the contractor's cost, and pricing data and how the government solicits and evaluates bids may be streamlined.6 Many provisions in the two bills expand the range of what may be considered commercial items, thus exempting them from these and other regulations.

Intending to make buying commercial products easier, the House included a provision in its bill, Section 801, to "establish a program to procure commercial products through online marketplaces for purposes of expediting procurement and ensuring reasonable pricing of commercial products." In explaining the provision, Representative Thornberry stated: "If you're buying office supplies, you ought to be able to go on Amazon and do it."7

Representative Thornberry also expected that over time DOD would expand the types of products it purchases through the online marketplaces, as described in the committee report: "The committee expects, however, that opportunities to purchase additional products through marketplaces may arise as GSA gains familiarity with the use of online marketplaces."8 The provision also includes guidelines to ensure marketplaces comply with certain acquisition regulations, such as compliance with domestic sourcing mandates and small business participation requirements, and handling of suspended or debarred contractors.

Some observers have expressed concern the provision will not increase competition (and therefore not reduce costs), which is one of the key reasons for Congress's effort to promote purchasing commercial items.9

The Senate's subtitle E, "Provisions Related to Commercial Items," specifically includes items that expand what is considered a commercial item.

- Section 852 adds sales to foreign governments to those made to state and local governments, rendering all three as qualifications for considering an item a commercial item.

- Section 853 asserts that once an item is acquired as a commercial item, it is always considered a commercial item.

- Section 854 asserts the preference for commercial items supersedes small business set-asides.

- Section 855 mandates a review of those regulations and laws applicable to commercial items, with a presumption they will be made inapplicable. It also eliminates clauses currently required in contracts and subcontracts for commercial items, to ease their procurement.

- Section 851 would modify the statutory definition of a commercial item to rule out an item so modified it "includes a preponderance of government-unique functions or essential characteristics." Such a standard may restrict what is considered a commercial item. However, depending on how modifications are judged, it may also expand what is a commercial item by allowing more modification.

Section 803 of the House bill would raise the dollar threshold at which a contractor must provide the government cost or pricing data under the Truth in Negotiations Act (TINA) from $500,000 to $2.5 million. Section 813 of the Senate bill would also raise the threshold, but only to $1 million. These increased thresholds allow more products to be treated like commercial items, which are already exempt, for the purposes of TINA. Raising the threshold would generally reduce the compliance burden on contractors, but would also reduce government access to data supporting a contractor's purported pricing. In addition, Section 866 of the Senate bill's subtitle G makes prior foreign military sales a justification for exempting a transaction from TINA.

Section 812 of the Senate bill also would raise the simplified acquisition threshold for DOD from the government-wide threshold of $100,000 to $250,000. Purchases under the simplified acquisition threshold are exempt from a number of regulations and laws, giving such acquisitions commercial-like characteristics.10

To ensure contracting and procurement officers understand these and other features of commercial items, Section 866 of the House bill and Section 841 of the Senate bill use similar, though not exact, language which would require training on acquiring commercial items.

In contrast to these efforts to expand the use of commercial items, the Senate committee report also includes directive report language that cautions against unguarded use of commercial items and services. In discussing U.S. Transportation Command's ability to share information across unclassified networks with its commercial partners, the report states "While commercial service providers can offer innovation, efficiencies, and cost savings, these benefits should not be to the detriment of security or other military unique standards."11 The report also expresses concern that program managers are relying too much on commercial power supplies: "The fact remains, commercially available power supplies remain a primary failure mode of military systems."12 Finally, the report directs GAO to study whether some suppliers are overcharging DOD for spare parts by "disguising their cost structures from procurement officers," which the suppliers have done at least partly by claiming their items are commercial items.13

Service Contracts

Both chambers emphasized oversight of service contracts. The House report states "The bill increases oversight of service contracts, which constitute a majority of Department of Defense contracting dollars." The Senate report also emphasizes "[t]he sheer size, complexity, and value of these service contracts."14 GAO has found that despite this scale both DOD and Congress track the funding spent on products better than they do the funding spent on services.15

Both chambers seek to better evaluate the services contracts DOD lets. The Senate bill would prohibit DOD from entering into service contracts unless they were measured by outcome or performance rather than effort—for example, the number of bathrooms to be cleaned rather than hours spent cleaning bathrooms—unless DOD provides a justification (§818). The House bill would not require outcome-based measures, but House report language directs the Secretary of Defense to evaluate their use.16 The House bill emphasizes similar points by directing existing review boards to assess the need for the contract rather than how well the contract complies with regulations (§814), and it encourages the use of common guidelines for evaluating the need for services contracts (§869).

Both bills seek greater visibility of service contracts. The Senate bill requires DOD to provide an estimate of the number of service contracts and their total cost in DOD's five-year plan (§829). The House bill requires only information on the first year but that it be displayed by category in a common way across all DOD organizations (§814).

The Senate bill would create a temporary authority for DOD to enter into multiyear services contracts for up to 15 years instead of the current limit of 5 years (§819) and would echo the emphasis on commercial products by requiring the Secretary of Defense to list industries where there are significant numbers of commercial services providers (§820).

Finally, the House bill again contains a provision limiting the total amount spent on services contracts to the amount requested in FY2010 (§870). This limit was enacted from FY2012 to FY2015. Although the House bill carried an extension in FY2016 and FY2017, neither provision was enacted.

"Other Transaction" (OT) Authority

Both bills seek to increase DOD's use of "other transaction" (OT) authority. An OT is a special vehicle that allows DOD, using the authority found in 10 U.S.C. §2371, to enter into transactions with private organizations for basic, applied, and advanced research projects.17 An OT, in practice, is defined in the negative: an OT is not a contract, grant, or cooperative agreement, and its advantages come mostly from OTs not being subject to certain procurement statutes and acquisition regulations.18

The Senate bill includes a subtitle dedicated to such transactions. The Senate bill Section 871 and House bill Section 855 would both extend this authority to include developing prototypes. The Senate bill would also

- require education and training on OT (§872),

- set a preference for using OT for science and technology projects (§873), and

- list OT as an authorized means to perform research and development programs (§874).

While the House bill does not include similar provisions, it does include report language directing the Secretary of Defense to provide a briefing "on ways to improve the use of other transactions."19

Section 814 of the Senate bill would extend what counts as competitive procedures in soliciting bids. Currently, DOD can use peer or scientific reviews of proposals to select who conducts basic research. The provision would allow DOD to also use such reviews to select who conducts applied and advanced research and development projects, and who builds prototypes. While not formally an OT authority under 10 U.S.C. 2371, the provision expands how DOD can enter into agreements for similar purposes.

Intellectual Property

The House and Senate bills also both focus on bolstering DOD's role in acquiring intellectual property rights for the goods and services it procures. DOD seeks intellectual property rights to ensure the department does not become beholden to a single contractor.20 However, some—particularly in industry—fear government claims to intellectual property rights will limit innovation.21

The House bill would require that DOD negotiate a price for a major weapon system's technical data before entering into a development or production contract (§812). The bill would also create an office within the Office of the Secretary of Defense to help negotiate these rights and promulgate policy and guidance on acquiring intellectual property rights (§813).

The Senate bill would expand the statutory definition of technical data for software programs and what contractors must provide when delivering software programs (§881).

Additionally, the Senate bill would require the U.S. government to retain the rights to medical research developed exclusively with federal funds (§892). The bill also requires DOD to report when a prime contractor limits its subcontractors' intellectual property rights, a concern which most often stems from a subcontractor believing it has not received fair payment for intellectual property it developed (§899). A directed GAO study on spare parts suppliers may involve intellectual property rights as well; some of the concerns that prompted the GAO study stemmed from suppliers claiming proprietary intellectual property locked the government into unfavorable prices.22

Acquisition System Management

Following on previous efforts to reform acquisition process management, both bills again propose changing parts of the process.

- Section 804 of the Senate bill would direct that the defense-specific acquisition regulations adopt language stating the purpose of the defense acquisition system.

- Section 811 of the House bill would insert new requirements to consider "reliability and maintainability" when DOD designs weapon systems. The House bill would also codify use of operating and support costs in evaluating major programs at every stage of acquisition (§852).

- Section 806 of the Senate bill would require a report on whether Special Operations Command should have the same acquisition authorities as the military departments.

The bills also address data analytics, should-cost management, software acquisition, and revising previous reforms.

Data Analytics

Both bills include provisions to enhance DOD's use of data to manage acquisition and other processes. Most of the data analytics provisions seem to respond to concerns that DOD is not effectively using data—especially centralized data—to support decisionmaking.23 Section 831 of the House bill would require DOD to establish an architecture that extracts, stores, and displays data from every DOD component in a standard format to make those data better available to the Secretary of Defense. These data would cover

- accounting for expenditures,

- budget and programming data,

- acquisition costs and other data, including operating and support (O&S) and maintenance, and

- contracts and task orders.

The Senate bill would create pilot programs to integrate data from across DOD (§937) covering

- the budget,

- logistics,

- personnel security and insider threats, and

- two other "challenges" identified by the Secretary of Defense.

The Senate bill would require greater use of data analytics in the acquisition process by directing DOD to collect and share more data (§936).

The House bill would require that DOD provide more data to Congress in its annual budget documents, including specific displays of funding for major programs' test and evaluation, developmental and operational, as well as purchasing cost and technical data from contractors (§832).

Section 833 would require more information on operational test and evaluation. However, while most of the data analytics provisions seem to respond to concerns DOD is not effectively using data, Section 833 appears to respond to concerns that independent testers are not fully considering military service perspectives.24 Specifically, it requires the independent Director of Operational Test and Evaluation to explain why he is reviewing certain programs, to allow military departments to comment on his reports, and to contrast how the capabilities of new systems would improve on older systems regardless of whether those capabilities are testing well or not.25

Should-Cost Management

Section 803 of the Senate bill would mandate regulating "should-cost" reviews—a DOD initiative of the past few years intended to lower prices DOD pays—to ensure the contractor on a program is treated fairly.26 The House did not include such a provision, but its report language shows a similar concern about how contractors are treated and requires a briefing from the Secretary of Defense.27

Software Acquisition

The Senate bill includes a series of provisions reforming DOD's purchasing of software. Section 835 of the Senate bill would stipulate that software programs, like automated information or defense business systems, are not major defense acquisition programs, which require a high level of oversight. Sections 883 to 885 would require DOD to identify software-intensive major programs, defense business systems, and software to be developed and acquired using "agile" methods. The sections define "agile" methods as "delivering multiple, rapid, incremental capabilities to the user for operational use, evaluation, and feedback" using "the incremental development and fielding capabilities, commonly called 'spirals,' 'spins,' or 'sprints,' which can be measured in a few weeks or months." Furthermore, Section 886 would mandate that all unclassified software developed for DOD be managed as open source software.

Revising Previous Reforms

Finally, the bills propose revising several reform provisions enacted in the past two years' NDAAs.

- The Senate bill would

- require confirmation of the Under Secretary for Research and Engineering created in the FY2017 NDAA instead of allowing the incumbent Under Secretary for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics to assume the position with no confirmation hearing (§905);

- downgrade the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment (A&S) created in the FY2017 NDAA from an Executive Schedule II position to an Executive Schedule III (§904); and

- clarify that A&S has only "advisory authority" rather than "supervisory authority" over programs the military services are managing (§903).

- Section 854 of the House bill would amend the FY2017 requirement for sustainment reviews to allow the Under Secretary for Acquisition and Sustainment to see the documents submitted during the reviews.

- Section 825 in the Senate bill and Section 856 in the House bill would add two cases to the FY2017 language that limited when lowest-price, technically acceptable (LPTA) criteria could be used to select contractors for programs;

- The House section would add electronic test and measurement equipment as a case in which LPTA shall be avoided.

- The Senate bill goes on to prohibit the use of LPTA for all major defense acquisition programs, which are principally programs so designated by the Secretary of Defense (§836).28

The FY2016 bill created a penalty to the military departments if the programs they manage fare poorly: 3% of the cost overruns in the major programs the department manages would be transferred from the department's research, development, testing and evaluation accounts to a Rapid Acquisition Prototyping Fund created by that act and managed within the Office of the Secretary of Defense. The original language allowed cost overruns to be offset by underruns, but Section 827 of the Senate bill would eliminate that offset.

Common Provisions

While most of the areas discussed above were of shared interest to both chambers, the bills do not agree on how to address those areas. Other provisions, however, have nearly identical language indicating that the chambers already agree how to address them.

- House bill Section 843 and Senate bill Section 899B would except contracted DOD operations from using $1 coins.

- House bill Section 842 and Senate bill Section 899A would extend from 20 years to 30 years the maximum length contracts can be let to store, handle, or distribute liquid fuels and natural gas.

- House bill Section 851 and Senate bill Section 823 would limit contracting officers to "definitizing" contracts only after a certain period has elapsed once the contracting officer notifies the contractor of the impending definitization. "Definitizing" refers to specifying on what terms a contract is being executed; some contracts can be signed before all of the terms are agreed. The House bill applies these limits to contract actions greater than $1 billion and after 30 days elapse while the Senate bill applies the limits to actions greater than $50 million and after 60 days elapse.

- House bill Section 863 and Senate bill Section 824 would add safety equipment to those items for which a contractor may not be selected based on a lowest price technically acceptable methodology. The House bill only includes aviation critical safety equipment.

- House bill Section 867 would require DOD websites posting contracting opportunities to notify small businesses they may be eligible for free federal procurement technical assistance services. The Senate report includes similar directive report language.29 House bill Section 853 would allow Procurement Technical Assistance Centers (PTACs)—local entities that help small businesses navigate DOD contracting—to carry over income to another fiscal year. The Senate report includes directive report language encouraging the Defense Logistics Agency to fund a greater share of some PTACs.30

- House bill Section 868 would require a GAO report on a FY2013-authorized program to improve contractors' business systems' ability to provide information to DOD. Senate report language directs a similar study.31

Both bills adjust what items must be procured from manufacturers in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Australia as defined by 10 U.S.C. 2500(1). The Senate bill in Section 863 sunsets the requirement to buy all items but ball and roller bearings from such manufacturers. In contrast, House bill Section 862 adds the components for auxiliary ships to the existing list.

Conclusion

Both chambers' versions of the National Defense Authorization Act demonstrate Congress's continued interest in reforming the defense acquisition process. While less momentous than the past year's organizational change breaking DOD's acquisition office into two parts, the FY2018 bills contain a number of provisions that, if enacted, will continue changing the DOD acquisition system.