Introduction

The Gulf of Mexico coastal region (Gulf Coast) stretches over the shoreline areas of five U.S. states: Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida. The coastal environment has been altered over time due to changes in hydrology, loss of barrier islands and coastal wetland habitat, issues associated with low water quality, human development, and natural processes, among other things. The federal government has addressed these changes through ecosystem restoration activities in the region over the past few decades. Major restoration projects led by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (Corps), the Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) have been implemented. Significant state and local efforts to restore the Gulf Coast have also been undertaken, in some cases in consultation with the federal government.

The Gulf Coast has also been affected by large-scale natural and manmade disasters that have significantly affected the environment and economy of the region. Indeed, these disasters have led to changes in restoration efforts, sometimes in a significant fashion. For example, in 2005, Hurricanes Katrina and Rita caused widespread damage to wetland and coastal areas along the Gulf, and altered the plans for restoring some parts of the coast. In 2010, a manmade disaster, the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, resulted in an unprecedented discharge of oil in U.S. waters and oiling of over 1,100 miles of U.S. shoreline.

Introduction to Deepwater Horizon Restoration

The oil spill had short-term ecological effects on coastal habitats and species, and is expected to result in long-term ecological effects (these effects are largely uncertain). This spill increased attention toward the Gulf Coast environment and modified perceptions about restoring the Gulf Coast ecosystem. In particular, the oil spill focused attention on the natural resources impacted by the incident and long-term natural resource restoration issues that existed before the spill.

As an identified responsible party,1 the oil and gas company BP is liable for response (i.e., cleanup) costs, as well as specified economic and natural resource damages related to the spill.2 As of the date of this report, oil cleanup operations have diminished substantially, and various claims processes seeking to compensate parties for damages related to the spill have been settled. Some funds already have been released and targeted toward environmental and economic restoration. Some of the primary funding streams include the following:

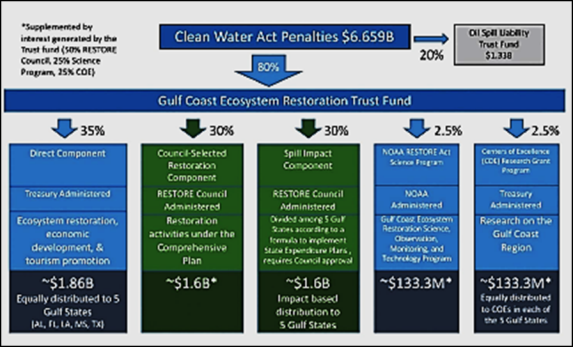

- Clean Water Act (CWA) civil damages paid by responsible parties, 80% of which are expected to support the efforts outlined under the Resources and Ecosystems, Sustainability, Tourist Opportunities, and Revived Economies act of the Gulf Coast States Act of 2012 (Subtitle F of P.L. 112-141, also known as the RESTORE Act);

- other CWA civil and criminal penalties, including funding for projects to be selected by the nonprofit National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF) under court settlements; and

- funding to compensate for spill impacts through the Natural Resources Damage Assessment (NRDA) process, a component of oil spill liability pursuant to the Oil Pollution Act.3

Each of these funding streams is subject to its own conditions, priorities, and processes, and is expected to be overseen by different entities. In some cases, funds may be spent only on restoration of habitat damaged by the oil spill. In other cases, funds can address a wider range of issues, such as economic development.

Introduction to Congressional Role

Congress has varying degrees of oversight and control over the dissemination of funding to restore the Gulf Coast. The RESTORE Act, enacted in July 2012, established a framework for the dissemination of expected civil penalties under the Clean Water Act. In this act, to provide for long-term environmental and economic restoration of the region, Congress authorized the creation of a trust fund to collect monies derived from these penalties, established guidelines for allocating and awarding funds for ecosystem and economic restoration, and provided for monitoring and reporting on progress of restoration. Separately, Congress also has an interest in overseeing other ongoing restoration processes, including the NRDA process (implemented by NOAA, pursuant to the Oil Spill Pollution Act) and the allocation of restoration funds to NFWF, an independent nonprofit that was established and funded by Congress and is subject to congressional oversight. In addition to these funding streams, Congress also funds (through discretionary appropriations) and oversees multiple federal agencies conducting ongoing restoration actions in the Gulf Coast region that are often related to, but in some cases undertaken apart from, activities initiated since the Deepwater Horizon spill.

Restoration of the Gulf Coast is complicated from a congressional perspective because multiple restoration processes are interrelated, but largely occur outside of the traditional appropriations process (including funds being used by nonfederal sources). With multiple sources of funding for ecosystem and economic restoration, Congress may be interested in how one or more restoration processes implement their activities, how they coordinate with each other, and how they are approaching and affecting the restoration of the Gulf Coast.

The remainder of this report provides information on environmental damage and restoration activities related to the Deepwater Horizon spill. It includes an overview of previous, ongoing restoration work in the Gulf Coast region and a more detailed discussion of the implementation of the RESTORE Act and other Deepwater Horizon-related processes. It concludes with a discussion of potential issues for Congress.

Background on the Gulf Coast Ecosystem

The Gulf Coast region is home to more than 22 million people and 15,000 species over five southern states: Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida. Animal, plant, and microbial populations depend on the Gulf's unique processes to survive. Overall, the Gulf Coast environment includes multiple interconnected ecosystems spanning 600,000 square miles of shoreline of the Gulf of Mexico.4 These ecosystems provide services that encompass aesthetic, economic, and environmental values for their residents. For instance, barrier islands and wetland complexes may provide some coastal storm damage protection benefits for coastal communities. They provide habitat for a number of commercially and recreationally important species of fish, invertebrates, mammals, and birds, including many threatened and endangered species. These ecosystems also filter water, remove and trap contaminants, and store carbon, among other functions.

The Deepwater Horizon spill is one of several events and ongoing processes that have altered the Gulf Coast ecosystems over time. Prior to the spill, the ecosystems were undergoing large changes due to human development and natural processes. For example, large-scale sediment and habitat loss was occurring, in part, due to altered water flows from the Mississippi River; water pollution was being exacerbated by excess nutrients such as phosphorus and nitrogen; and waterways were being altered due to dredging and levee construction; among other things.5 The spill did not change many of these processes but altered perspectives on how federal and state governments approach restoration.

Prespill Federal Restoration Activities in the Gulf

Prior to the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, several federal agencies were involved in a number of efforts to restore and conserve ecosystems in the Gulf Coast region. These efforts ranged from large-scale restoration initiatives in particular ecosystems to grant programs and projects focusing on distinct restoration issues. For example, the Corps is involved with the state of Louisiana in an initiative that aims to restore wetlands and reduce wetland loss in coastal Louisiana. The program, termed the Louisiana Coastal Area Program, is expected to entail the construction of coastal restoration features that involve habitat restoration and dredging, among other things. The Appendix to this report outlines the major ongoing federal restoration efforts and initiatives in the Gulf.6 Several interagency forums coordinate federal stewardship efforts and collaborative planning for Gulf Coast projects, some in cooperation with state, nonprofit, and local entities.

Over the years, the Gulf Coast region has not been addressed comprehensively as an area for restoration. There has been no overarching restoration initiative addressing the region, possibly because of the size of the region and variability in its ecosystems and governing entities. Further, there has been no central entity or program responsible for planning or implementing restoration activities. Instead, responsibilities have varied by area, timing, and scope, with various combinations of federal, state, local, and nonprofit entities implementing (and in some cases directing) restoration. For instance, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas have major ongoing Corps restoration plans focused on specific projects and ecosystems. These are federal/state partnerships and differ in terms of how far projects have progressed. There are no comparable coastal initiatives in Alabama or in the northern part of Florida.7 In these areas, states, along with other entities, have initiated restoration efforts. Further complicating a comprehensive effort to restore the region is the complexity of ecological issues in the region and their connection to ecosystems outside of the region. For example, excess nutrients that cause hypoxia in the Gulf Coast area are attributed in part to agricultural runoff in the northern reaches of the Mississippi River. Addressing restoration in the Gulf Coast cuts across regions and ecosystems, as well as departmental and agency jurisdictions within the federal government.

Efforts at unifying federal agency actions and developing a process for restoring the Gulf Coast region were initiated by the Obama Administration and predated the Deepwater Horizon spill. The Obama Administration created a Gulf Coast Ecosystem Restoration Working Group, which was tasked with developing a strategy for restoring the Gulf Coast region.8 The strategy is termed the Roadmap for Restoring Ecosystem Resiliency and Sustainability in the Louisiana and Mississippi Coasts. The intent of the roadmap was to guide near-term restoration actions to be undertaken by agencies within the working group, and facilitate the coordination of federal restoration and protection activities. However, the Deepwater Horizon spill and resulting damages and financial compensation from litigation altered the federal government's approach to restoration and coordination. Some of the new processes that have developed as a result of the oil spill are discussed below.

Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill: Environmental Impacts

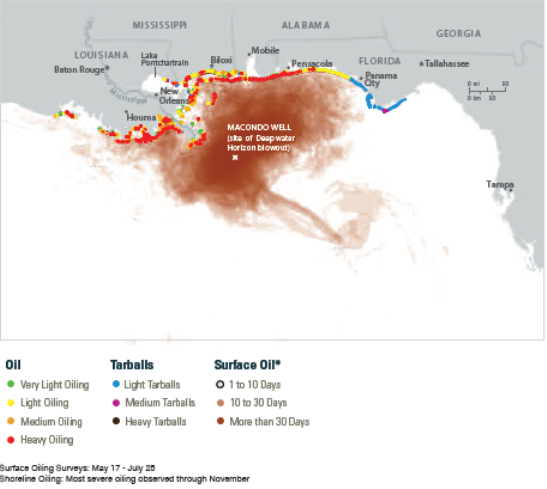

The explosion of the Deepwater Horizon offshore drilling rig on April 20, 2010, which took place 41 miles southeast of the Louisiana coast, resulted in an estimated 171 million gallons (4.1 million barrels) of oil discharged into the Gulf of Mexico over 84 days.9 An additional 35 million gallons of oil escaped the well, but did not enter the Gulf environment, because BP recovered this oil directly from the wellhead.10 At the time these calculations were made (July 14, 2010), approximately 50% of the oil had evaporated, dissolved, or been effectively removed from the Gulf environment through human activities. However, a substantial portion—over 100 million gallons—remained, in some form, in the Gulf of Mexico. The fate of the remaining oil in the Gulf is uncertain and might never be determined conclusively. Multiple challenges hinder determination of the fate of the oil, and as time progresses, determining the fate of the oil and related environmental impacts will likely become more difficult. Some study results indicate that microbial organisms (bacteria) consumed and broke down a considerable amount of the oil in the water column.11

The effects from the oil spill were spread throughout the Gulf Coast ecosystem. In the immediate aftermath of the spill, more than 88,522 square miles of coast were closed and almost 1,100 miles of shoreline and related habitat were damaged due to oiling.12 A map of some of the documented oiling impacts in the immediate area of the oil spill is shown below in Figure 1.13

|

|

Source: National Commission on the BP Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill and Offshore Drilling, Deep Water: The Gulf Oil Disaster and the Future of Offshore Drilling, Report to the President, January 2011. |

Several scientists have noted that the long-term effects of the spill are likely to persist into the future.14 One of the earliest reports on the oil spill, carried out by a presidential task force under the direction of former Secretary of the Navy Ray Mabus,15 divided the effects of the oil spill into four categories:

- 1. Water Column Effects: Due to the location and scale of the oil spill, the spill is expected to have impacts on the food chain in coastal areas.

- 2. Fisheries Effects: The oil spill led to the temporary closure of approximately 36% of federal Gulf waters, as well as in-state waters, to fishing. Although these waters have subsequently been reopened, studies on fisheries impacts are ongoing, and impacts from oil on fish eggs and larvae may be better understood over time.

- 3. Effects on Other Species: Animals face both short-term and long-term impacts from the oil spill, including impacts on food availability, growth, reproduction, behavior, and disease.

- 4. Habitat Effects: Beaches, wetlands, and other Gulf Coats habitats were exposed to oil, which could potentially exacerbate erosion issues in the region and kill plants and animals.

Specific long-term effects on the ecosystem are still being studied. Documented effects have been reported by scientists for various aspects of the ecosystem. For example, scientists provided estimates on the effect of the oil plume on deep sea sediment habitat and species around the well head. They reported that the most severe reduction of biodiversity in this habitat extended 3 km around the wellhead, and that moderate impacts were observed up to 17 km southwest and 8.5 km northeast of the wellhead.16 Further, scientists estimated that recovery rates for this habitat could be in terms of decades or longer.17 The effects on the seafood industry are also being calculated economically and environmentally for the long term.18

Federal Restoration in the Gulf since the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill

After the oil spill, efforts were focused on addressing the immediate impacts of the oil spill and monitoring how the spill was spreading through the ecosystems. Although the Oil Pollution Act (OPA) liability provisions19 are meant to address natural resource damages related to the oil spill, many policymakers and stakeholders expressed an interest in also addressing prespill natural resource issues in the Gulf. Thus, to some degree, Gulf restoration activities may be divided into short-term efforts that address natural resource impacts related to the 2010 oil spill and long-term recovery efforts that address restoration issues in place well before the 2010 spill.20

Mabus Report and Gulf Coast Ecosystem Restoration Task Force

The impetus for long-term environmental restoration and recovery efforts related to the oil spill can be traced, in part, to a September 2010 report commissioned by the Obama Administration and under the direction of former Secretary of the Navy Ray Mabus (also known as the "Mabus Report").21 The report outlined existing processes as well as potential new funding sources for Gulf Coast restoration. The final report noted the multiple challenges facing the Gulf Coast and suggested incorporating them into the response to the oil spill:

This is a region that was already struggling with urgent environmental challenges.... [I]t only makes sense to look at the broader challenges facing the system and to leverage ongoing efforts to find solutions to some of the complex problems that face the Gulf. Sustained activities that restore the critical ecosystem functions of the Gulf will be needed to support and sustain the region's economic revitalization.22

The report made a number of recommendations for future restoration actions to address this challenge. Most importantly, the Mabus Report recommended the dedication of civil penalties under the Clean Water Act toward Gulf restoration to address recovery needs that may fall outside the scope of natural resource damages under the OPA.23 It further recommended that "Congress establish a Gulf Coast Recovery Council that should focus on improving the economy and public health of the Gulf Coast, and on ecosystem restoration not dealt with under [OPA's Natural Resource Damage Assessment program]. These three areas are inextricably linked to the successful recovery of the region."24

To further the long-term restoration objectives outlined in the Mabus Report, President Obama established the Gulf Coast Ecosystem Restoration Task Force in October 2010.25 The task force held meetings, met with public officials, and produced a restoration strategy in December 2011, which was expected to guide future restoration efforts in the region.26 The task force strategy defined ecosystem restoration goals and described milestones toward reaching those goals; considered existing research and ecosystem restoration planning efforts; identified major policy areas where coordinated actions between government agencies were needed; and evaluated existing research and monitoring programs and gaps in data collection. The task force goals for Gulf Coast restoration were

- restore and conserve habitat;

- restore water quality;

- replenish and protect living coastal and marine resources; and

- enhance community resilience.

Enactment of the RESTORE Act in P.L. 112-141 (discussed below) in July 2012 resulted in the creation of the Gulf Coast Ecosystem Restoration Council and led to President Obama disbanding the task force.27

Environmental and Economic Restoration Efforts and Funding

Since the oil spill, congressional legislation, civil and criminal settlements relating to oil spill damages, and existing federal programs have initiated a number of actions intended to restore the ecosystems and economies in the Gulf Coast region. Many of these actions are related, but have different planning processes and time lines, leadership, and goals. The below sections focus on the three most significant efforts aimed at environmentally and economically restoring the Gulf Coast region:

- RESTORE Act funding/Gulf Coast Ecosystem Restoration Trust Fund;

- National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF) Gulf Coast Restoration Funding; and

- Natural Resource Damages (NRD) under the Oil Pollution Act.

It is expected that in total, more than $18.3 billion will go to these three efforts pursuant to civil and criminal settlements with responsible parties.28 A summary of civil and criminal settlements to date and their required funding allocations is provided in the Appendix to this report. Although economic claims and other payments to individuals damaged by the spill may in some cases be used contribute to or complement the activities discussed below, they are not included in this discussion.29

In addition to these efforts, funding for Gulf Coast restoration activities also is being made available under a number of smaller settlements and through ongoing federal agency activities (as discussed above). Some of these efforts are referenced in Table A-2, below.

RESTORE Act/Gulf Coast Ecosystem Restoration Trust Fund

The RESTORE Act is a subtitle in legislation (MAP-21; P.L. 112-141) enacted on July 6, 2012.30 The RESTORE Act establishes the Gulf Coast Restoration Trust Fund in the General Treasury. Eighty percent of any administrative and civil Clean Water Act (CWA) Section 31131 penalties paid by responsible parties in connection with the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill are deposited in the fund.32 Amounts in the trust fund will be available for expenditure without further appropriation. The act directs the Secretary of the Treasury to promulgate implementing regulations concerning trust fund deposits and expenditures.33 Pursuant to CWA civil settlements, it is expected that approximately $5.5 billion in CWA penalties will be available through the trust fund through FY2031.

Fund Administration

The RESTORE Act gives the Secretary of the Treasury authority to determine how much money from the Gulf Coast Restoration Trust Fund should be expended each fiscal year, and regulations from the Treasury Department have since confirmed this approach. In accordance with the RESTORE Act and Treasury regulations, for each fiscal year the Secretary of the Treasury is to release funds from the trust fund toward the required components (discussed below), and invest the remainder "that are not, in the judgment of the Secretary, required to meet needs for current withdrawals."34 These investments are to be in interest-bearing obligations of the United States with maturities suitable to the needs of the trust fund. The Secretary also has authority to audit and stop expending funds to particular entities (e.g., states), if the Secretary determines funds are not being used for prescribed activities. The authority of the trust fund terminates when all funds owed to the trust fund have been provided and all funds from the trust fund have been expended.

Funding Distribution and Authorized Uses

The RESTORE Act distributes monies from the Gulf Coast Restoration Fund to various entities through multiple processes, or "components." All of the funds—not counting authorized administrative activities—would support activities in one or more of the five Gulf of Mexico states. The different fund allotments and their conditions are discussed below and illustrated in Figure 2. The largest component is the "Direct Component," under which 35% of Gulf Coast Restoration Trust Fund monies (an estimated $1.86 billion based on the settlements with BP, Transocean, and Anadarko) will be distributed directly by Treasury equally to the five states. Other major components include the Council-Selected Restoration Component (also referred to as the Comprehensive Plan Component), under which the council is to receive 30% for an ecosystem restoration plan (an estimated $1.86 billion, to be supplemented by interest generated by the trust fund), and the Spill Impact Component, under which the council will receive an additional 30% but will distribute this amount to states unequally (estimated at $1.6 billion total). Two other smaller allocations go toward science and research grants (2.5%, or $133.3 million, respectively). Each of these components is discussed in detail below. Pursuant to the Treasury regulations, no more than 3% of the amount received by the council and other political subdivisions (e.g., states, counties) for any of these components may be used for administrative expenses.

35%—Direct Component: Equal Shares to the Five Gulf States

The largest portion of the fund (35%, other than interest earned on investments) is to be divided equally among the five Gulf of Mexico states: Alabama, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas. The Treasury will provide this funding as grants to these states in a given fiscal year. The act has further requirements for specific distributions to political subdivisions in Florida and Louisiana. In Florida, the shares are to be divided among affected counties, with 75% of that state's share to be distributed to the eight "disproportionately affected" counties while the remaining 25% will go to "non-disproportionately impacted" counties. In Louisiana, 30% of its share goes to individual parishes based on a statutory formula, and the remainder goes to the state Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority Board. For other states, all of the funding will be distributed to similar state authorities or offices.35

The act stipulates that the state (or county) funding must be applied toward one or more of the following 11 activities:36

- 1. Restoration and protection of the natural resources, ecosystems, fisheries, marine and wildlife habitats, beaches, and coastal wetlands of the Gulf Coast region.

- 2. Mitigation of damage to fish, wildlife, and natural resources.

- 3. Implementation of a federally approved marine, coastal, or comprehensive conservation management plan, including fisheries monitoring.

- 4. Workforce development and job creation.

- 5. Improvements to or on state parks located in coastal areas affected by the Deepwater Horizon oil spill.

- 6. Infrastructure projects benefitting the economy or ecological resources, including port infrastructure.

- 7. Coastal flood protection and related infrastructure.

- 8. Planning assistance.

- 9. Administrative costs (limited to not more than 3% of a state's allotment).

- 10. Promotion of tourism in the Gulf Coast Region, including recreational fishing.

- 11. Promotion of the consumption of seafood harvested from the Gulf Coast Region.

Subsequently, the Treasury regulations for the program outlined a similar set of activities but noted that the first six activities above are eligible only to the extent that they are carried out in the Gulf Coast region.37 To receive its share of funds (which are to be distributed as a grant), a state must meet several conditions, including a certification (as determined by the Secretary of the Treasury) that, among other things, funds are applied to one of the above activities and that activities are selected through public input. In addition, states must submit a multi-year implementation plan, documenting activities for which they receive funding.

The RESTORE Act further stipulates that each state must agree to meet conditions for receiving funds that are promulgated by the Secretary of the Treasury, and certify that requested projects meet certain conditions.38 These conditions include that projects (1) are designed to restore and protect natural resources of the Gulf Coast environment or economy; (2) carry out one or more of the 11 activities described above; (3) were selected with public input; and (4) are based on the best available science. Under the RESTORE Act, the states are required to develop and submit a multiyear implementation plan for the use of received funds, which may include milestones, projected completion of the project, and mechanisms to evaluate progress.39 States also can use funds to satisfy requirements for the nonfederal cost share of authorized federal projects.40

30%—Gulf Coast Ecosystem Restoration Council Comprehensive Plan

The RESTORE Act authorizes the creation of a new council to govern the majority of ecosystem restoration efforts under the bill. The council is named the Gulf Coast Ecosystem Restoration Council and contains representatives from high-level officials from six federal agencies and the governor (or his/her designee) from each of the five Gulf Coast states. The act provides for the distribution of 30% of all revenues of the Gulf Coast Restoration Trust Fund, plus one-half of the interest earned on investments, to the council to fund a comprehensive ecosystem restoration plan (termed the Comprehensive Plan). In addition to allocating this funding toward restoration, the council also is responsible for allocating 30% of the trust fund to Gulf States under a formula established in the RESTORE Act (see "30%—Spill Impact Component: Unequal Shares to the Five Gulf States," below, for details). The council is authorized to conduct several actions, including developing and revising the Comprehensive Plan; identifying and conceiving projects prior to enactment that could restore the ecosystem quickly; establishing advisory committees; collecting and considering scientific research; and submitting reports to Congress.

The council published its draft Initial Comprehensive Plan in August 2013, and initial projects to be included in the plan were solicited in August 2014. After a series of public meetings, on August 23, 2016, the council released a draft Comprehensive Plan Update, which included project level selections.41 The plan set in motion a series of subsequent public meetings and a formal comment period to update the Initial Comprehensive Plan to account for funding updates and public input. The plan was finalized by the council on December 16, 2016.42

The Comprehensive Plan establishes five broad restoration goals and details how the council will select and fund projects. Project selection criteria and evaluation reflects provisions under the RESTORE Act. The Comprehensive Plan is to address restoration under two components: the Restoration Component and the Spill Impact Component. Each component reflects conditions and criteria established under the RESTORE Act for funding. The Comprehensive Plan notes that selected projects under the Restoration Component might not be balanced according to the restoration goals.43 For example, projects that aim to restore, improve, and protect water quality (one of the goals) might outnumber projects that aim to restore and enhance natural processes and shorelines (another goal). Further, according to the Comprehensive Plan and the RESTORE Act, the responsibility for implementing a project under the plan is to be given to either a state or a federal agency. Therefore, the council may not be considered an implementing entity but rather should be considered a managing and oversight entity for restoration.44

The Comprehensive Plan 2016 Update includes a description of how funds from the trust fund will be allocated to implement the plan from 2017 to 2026.45 This element is referred to in the plan as the "10-Year Funding Strategy" and was required under the RESTORE Act.46 Further, the plan contains an initial project and program priority list that the council would be expected to fund over the next three years, as required under the RESTORE Act.47 This list is referred to as the "Funded Priorities List" and also was required under the RESTORE Act.48 Regulations by the Department of the Treasury have clarified that eligible activities for the Comprehensive Plan include activities in the Gulf Coast Region that would restore and protect the natural resources, ecosystems, fisheries, marine and wildlife habitats, beaches, coastal wetlands, and economy of the region.

30%—Spill Impact Component: Unequal Shares to the Five Gulf States

The act directs the council to disburse 30% of Gulf Coast Restoration Trust Fund monies to the five Gulf States based on the relative impact of the oil spill in each state. The council is to develop a distribution formula based on criteria listed in the act. In general, the criteria involve a measure of shoreline impact; oiled-shoreline distance from the Deepwater Horizon rig; and coastal population.49 On September 29, 2015, the council published a draft Spill Impact Component regulation in the Federal Register. The final rule was published in the Federal Register on December 15, 2015, and became effective April 4, 2016, with approval from the federal court in Louisiana.50 Based on the formula and information determined in the final rule, the allocation of Spill Impact Component funds to each state is as follows:

- Alabama—20.40%;

- Florida—18.36%;

- Louisiana—34.59%;

- Mississippi—19.07%; and

- Texas—7.58%.51

To receive funding, each state must submit a plan for approval to the council. State plans must document how funding will support one or more of the 11 categories listed in the "35%—Direct Component: Equal Shares to the Five Gulf States" section, above. Information and criteria for developing the state plans are included in the Comprehensive Plan Update.52 However, in contrast to the Direct Component, only 25% of a state's funding can be used to support infrastructure projects, which are those projects in categories six (infrastructure projects benefitting the economy or ecological resources, including port infrastructure) and seven (coastal flood protection and related infrastructure).53

2.5%—Gulf Coast Ecosystem Restoration Science, Observation, Monitoring, and Technology (GCERSOMT) Program

The act establishes the Gulf Coast Ecosystem Restoration Science, Observation, Monitoring, and Technology (GCERSOMT) program, funded by 2.5% of monies in the Gulf Coast Restoration Trust Fund. The NOAA administrator will implement the program, which is to support marine research projects that pertain to species in the Gulf of Mexico. Further, the program is to conduct monitoring and research on marine and estuarine ecosystems and collect data and stock assessments on fisheries and other marine and estuarine variables. There is an emphasis on coordination with other entities to conduct this work and provisions that instruct the administrator to avoid duplication of efforts. This program is to sunset when all funds in the trust fund are expended.

2.5%—Centers of Excellence

The act disburses 2.5% of monies in the Gulf Coast Restoration Trust Fund to the five Gulf States to establish—through a competitive grant program—centers of excellence. The centers would be nongovernmental entities (including public or private institutions) and consortia in the Gulf Coast Region. Centers of excellence are to focus on science, technology, and monitoring in at least one of the following areas: coastal and deltaic sustainability and restoration and protection; coastal fisheries and wildlife ecosystem research and monitoring in the Gulf Coast region; sustainable and economic growth and commercial development in the region; and mapping and monitoring of the Gulf of Mexico water body.

Interest Earned by the Fund

Interest earned by the Gulf Coast Restoration Trust Fund would be distributed as follows:

- 50% would fund the Gulf Coast Ecosystem Restoration Council to implement the Comprehensive Plan.

- 25% would provide additional funding for the Gulf Coast Ecosystem Restoration Science, Observation, Monitoring, and Technology program mentioned above.

- 25% would provide additional funding for the centers of excellence research grants mentioned above.

Funding Levels

Amounts of approximately $816 million and $128 million have been deposited in the Gulf Coast Restoration Trust Fund pursuant to 2013 and 2015 settlements with Transocean and Anadarko Petroleum Company.54 The April 2016 settlement with BP stated that BP would pay $5.5 billion to resolve CWA claims, 80% ($4.4 billion) of which is to be distributed to the trust fund according to the RESTORE Act. Together with the Transocean and Anadarko settlements, total funding would be $5.3 billion.

Status

As of spring 2017, the RESTORE Act components had distributed the following amounts:55

- Under the Direct Component, the Treasury Department has awarded approximately $26.7 million in funds to eligible entities. It also has allocated more than $200 million in "Multiyear Implementation Plans" under the Direct Component, a process required by the RESTORE Act and the Treasury final rule for eligible state, county, and parish applicants to prioritize activities for funds and to obtain public participation as part of preparing their multiyear plans.

- Under the Comprehensive Plan Component, the council has approved approximately $156.6 million in initial Funded Priorities List (FPL) projects. During 2016, 10 initial FPL projects totaling $34.68 million completed the application phase and were awarded funding.56

- Approximately $6 million in grants have been awarded for planning activities related to the Spill Impact Component. Spill Impact Component funds are to be invested in projects, programs, and activities identified in approved State Expenditure Plans (SEPs).57 Based on the formula established by the council, each state will develop one or more SEPs describing how it will use the allocated amount.58

- The NOAA RESTORE Act Science Program completed its first round of funding in September 2015, awarding approximately $2.7 million to seven research teams. The next funding round is expected to make awards later in 2017, with $17 million available for research projects.

- The Centers of Excellence Research Grants Program had awarded $16.816 million in grant program awards to eligible applicants as of April 2017.

As noted above, the Gulf Coast Ecosystem Restoration Council voted to approve the Comprehensive Plan Update on December 16, 2016. The plan established overarching goals based on the aforementioned Mabus Report,59 and it noted broad evaluation and selection criteria on which it plans to base its decisions. In accordance with the RESTORE Act, the plan includes project selections under the FPL as well as the 10-Year Funding Strategy.60 The Comprehensive Plan Update anticipated developing future FPLs approximately every three years.61

National Fish and Wildlife Foundation Funding

Pursuant to the criminal settlements between BP and the Department of Justice (DOJ) and between Transocean and DOJ in early 2013, National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF) was scheduled to receive more than $2.5 billion for Gulf Coast restoration over the five-year period from 2013 to 2017.62 NFWF was established by Congress in 1984. It is an independent 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization governed by a 30-member board of directors.63 The NFWF board is approved by the Secretary of the Interior and includes the Director of the Fish and Wildlife Service. In the past, it typically received limited federal funds, which it used to leverage grants for conservation purposes. NFWF also administers mitigation funds targeted to specific sites or projects, including roughly 160 different funds nationally as of June 2013.64

For purposes of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill recovery settlements, both criminal settlements direct NFWF to use the funds in the following manner:

- 50% (approximately $1.3 billion) of the funding is to support the creation or restoration of barrier islands off the coast of Louisiana and implementation of river diversion projects to create, preserve, or restore coastal habitats. These projects will "remedy harm to resources where there has been injury to, or destruction of, loss of, or loss of use of those resources resulting from the [Deepwater Horizon] oil spill."

- 50% of the funding is to support projects that "remedy harm to resources where there has been injury to, or destruction of, loss of, or loss of use of those resources resulting from the [Deepwater Horizon] oil spill." NFWF will support such projects in the Gulf states based on the following proportions: Alabama, 28% ($356 million); Florida, 28% ($356 million); Mississippi, 28% ($356 million); and Texas, 16% ($203 million).

Of these funds, the vast majority are expected to be made available to NFWF in the fourth and fifth years (2017 and 2018). The payment schedule and allocations to individual states are shown below in Table 1. For both the BP and Transocean settlement allocations, NFWF is directed to consult with "appropriate state resource managers, as well as federal resource managers that have the statutory authority for coordination or cooperation with private entities, to identify projects and to maximize the environmental benefits of such projects." For the Louisiana projects, NFWF is directed to consider the State Coastal Master Plan, as well as the Louisiana Coastal Area Mississippi River Hydrodynamic and Delta Management Study, as appropriate.65

Table 1. Schedule of Payments to NFWF Gulf Environmental Benefit Fund

(payments from BP and Transocean settlements in millions of dollars)

|

Date |

Louisiana |

Alabama |

Florida |

Mississippi |

Texas |

Total Payment |

|

Apr 2013 |

$79.00 |

$22.12 |

$22.12 |

$22.12 |

$12.64 |

$158.00 |

|

Feb 2014 |

176.50 |

49.42 |

49.42 |

49.42 |

28.24 |

353.00 |

|

Feb 2015 |

169.50 |

47.46 |

47.46 |

47.46 |

27.12 |

339.00 |

|

Feb 2016 |

150.00 |

42.00 |

42.00 |

42.00 |

24.00 |

300.00 |

|

Feb 2017 |

250.00 |

70.00 |

70.00 |

70.00 |

40.00 |

500.00 |

|

Feb 2018 |

474.00 |

125.16 |

125.16 |

125.16 |

71.52 |

894.00 |

|

Totals |

$1,272.00 |

$356.16 |

$356.16 |

$356.16 |

$203.52 |

$2,544.00 |

Source: National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, Gulf Environmental Benefit Fund Timetable, at http://www.nfwf.org/gulf/Pages/GEBF-Timetable.aspx.

Status

NFWF established the Gulf Environmental Benefit Fund (Gulf Fund) to receive funding to carry out Gulf Coast restoration efforts under the settlement. NFWF also reported that it is consulting with state and federal natural resource management agencies involved in other Gulf Coast restoration efforts (e.g., RESTORE and Natural Resource Damage processes). The first projects under the Gulf Fund were announced in November 2013. As of July 2017, NFWF reported that it had funded 101 Gulf Coast restoration projects worth approximately $880 million.66

Natural Resource Damages Under the Oil Pollution Act

The Oil Pollution Act of 1990 (OPA; P.L. 101-380), which became law after the Exxon Valdez oil spill of 1989, allows state, federal, and tribal governments to act as "trustees" to recover damages to natural resources in the public trust from the parties responsible for an oil spill. Under the OPA, responsible parties are liable for damages to natural resources, the measure of which includes the following:

- cost of restoring, rehabilitating, replacing, or acquiring the equivalent of the damaged natural resources;

- diminution in value of those natural resources pending restoration; and

- reasonable cost of assessing those damages.67

NOAA developed regulations pertaining to the process for natural resource damage assessment under the OPA in 1996.68 Natural resource damages may include both losses of direct use and passive uses. Direct-use value may derive from recreational (e.g., boating), commercial (e.g., fishing), or cultural or historical uses of the resource. In contrast, a passive-use value may derive from preserving the resource for its own sake or for enjoyment by future generations.69

The damages are compensatory, not punitive. Collected damages cannot be placed into the General Treasury revenues of the federal or state government but must be used to restore or replace lost resources.70 Indeed, NOAA's regulations focus on the costs of primary restoration—returning the resource to its baseline condition—and compensatory restoration—addressing interim losses of resources and their services.71

The Deepwater Horizon NRDA Trustees are

- the United States Department of the Interior;

- NOAA, on behalf of the United States Department of Commerce;

- the state of Louisiana's Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority, Oil Spill Coordinator's Office, Department of Environmental Quality, Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, and Department of Natural Resources;

- the state of Mississippi's Department of Environmental Quality;

- the state of Alabama's Department of Conservation and Natural Resources and Geological Survey of Alabama;

- the state of Florida's Department of Environmental Protection and Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission; and

- for the state of Texas, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, Texas General Land Office, and Texas Commission on Environmental Quality.

NRDA Process

When a spill occurs, natural resource trustees conduct a natural resource damage assessment to determine the extent of the harm. Trustees may include officials from federal agencies designated by the President, state agencies designated by the relevant governor, and representatives from tribal and foreign governments.

The trustees' work occurs in three steps: the preassessment phase, the restoration planning phase, and the restoration implementation phase. As of 2017, the Deepwater Horizon NRDA process is in the restoration implementation phase. During this phase, the trustees develop project-specific restoration plans and implement the projects in compliance with federal and state environmental laws.72 This process can take years, especially for complex incidents such as the Deepwater Horizon spill. However, during the NRDA process, early restoration projects can be completed to begin restoration of natural resources sooner than might otherwise be possible. This has been the case during the Deepwater Horizon NRDA process (see next section).

Status

The NRDA evaluation process is ongoing; however, as noted above, early restoration projects may be initiated in the meantime to allow for expedited restoration activities. On April 21, 2011, the trustees for the Deepwater Horizon oil spill announced an agreement with BP to provide $1 billion toward early restoration projects in the Gulf of Mexico to address injuries to natural resources caused by the spill. The agreement, known as the Framework for Early Restoration Addressing Injuries Resulting from the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill (or the Framework Agreement), provided the basis for subsequent early restoration actions.73 Under the Framework Agreement, a proposed early restoration project may be funded only if all of the trustees, DOJ, and BP agree on, among other things, the amount of funding to be provided by BP and the Natural Resources Damages Offsets (or NRD Offsets) that will be credited for that project against BP's liability for damages resulting from the spill. Following announcement of the Framework Agreement in 2011, the NRDA trustees solicited projects from the public.

Dissemination of early restoration funds has been divided into five phases as of July 2017. The first two phases of early restoration, announced in 2012, were completed and resulted in 10 projects at an estimated cost of approximately $71 million.74 On May 6, 2013, the trustees issued a notice in the Federal Register that included additional projects under a proposed Phase III.75 The plan for these projects, finalized in June 2014, proposed funding an additional 44 early restoration projects at a cost of approximately $627 million.76 On May 20, 2015, the trustees published a draft Phase IV plan proposing 10 early restoration projects with an estimated cost of $134 million.77 For Phase V, the trustees have selected the first phase of the Florida Coastal Access Project, which intends to enhance public access and recreational opportunities in the Florida Panhandle. The first part of that project, as described in the draft Phase V plan, estimates a cost of approximately $34.4 million, with a second phase of the project to be included in a future restoration plan. Thus, as of July 2017, the total funding allocated or spent on early restoration projects was $866 million for 65 projects.

The funding for the early restoration projects will be credited against BP's liability for natural resource damages resulting from the spill. Further, in early 2016, NOAA released a final damage assessment and restoration plan, which plans to fund a total of $8.8 billion in natural resource damages (i.e., early restoration projects) that were approved under the 2016 settlement with BP.78

Other Settlement Funding for Gulf Coast Restoration

In addition to the major restoration processes and funding mechanisms, civil and criminal pleas also have provided funding to other programs. This funding is generally of lesser magnitude than the RESTORE Act funding, the NFWF funding, and the NRDA funding, but it is expected to inform and complement this funding. To date, these funding allocations include

- $500 million to the National Academy of Sciences from the Transocean and BP criminal plea agreements, to be used for research on human health and environmental protection in the Gulf Region. It is also to be used for research on oil spill prevention and spill response strategies in the Gulf.

- $100 million to the North American Wetlands Conservation Fund from the BP criminal plea agreement for wetlands restoration, conservation, and projects benefiting migratory birds.

Potential Issues and Questions for Congress

Many of the ongoing Gulf Coast restoration efforts discussed above have yet to be finalized, and the planning processes and funds available for deposit into the Gulf Coast Restoration Trust Fund have yet to be fully determined. Further, project priority lists, state implementation plans, and other required restoration planning documents are still being developed. Nevertheless, a number of issues may be of interest to Congress in its oversight role related to Gulf Coast restoration. Some of these issues include the coordination of restoration activities among implementing entities; the development and implementation of a comprehensive plan for restoration; governance of restoration activities; and the balancing of the dual goals of ecological restoration and economic development in the Gulf Coast region.

Coordination

The coordination of restoration efforts among the multiple implementing entities in the Gulf Coast region is one likely area of congressional interest. As discussed above, several disparate streams of funding and resources are going toward new and existing restoration activities in the Gulf. These restoration activities are to be planned and implemented according to multiple planning documents and processes. For example, efforts conducted by NFWF will be done under its planning process after consultation with state and federal entities, while the council will be conducting its own coordination with state and federal agencies and governments for disbursing funds from the Gulf Coast Restoration Trust Fund pursuant to the RESTORE Act. Although the primary entities have highlighted coordination of their efforts, there is no formal entity that oversees all ongoing restoration in the Gulf nor is there a formal coordination process required among the implementing entities. This lack of formal requirements may cause concerns among some related to the potential duplication of projects, implementation of restoration projects that address the same issue yet promote different solutions, or projects with conflicting goals at local and regional levels. However, others may argue that formal coordination has not been necessary, as the informal coordination among the multiple restoration entities has thus far been effective.

The 2016 Comprehensive Plan Update under the RESTORE Act acknowledges some of these potential shortfalls and discusses the council's intention to coordinate among implementing entities. For example, the Comprehensive Plan states that the council will strive to coordinate with other partners involved in restoration activities to "maximize ecological and socio-economic benefits and avoid duplication."79 The RESTORE Act itself also includes some requirements related to coordination, although it does not provide for a congressionally authorized coordinating entity with authority over all relevant processes going forward.80 The act authorizes memoranda of understanding between the council and federal agencies to establish integrated funding and implementation plans, which could reduce project duplication and promote an integrated restoration effort among federal entities.81 It also addresses duplication of efforts in relation to monitoring the Gulf Coast ecosystem. The RESTORE Act requires the Gulf Coast Science Program to avoid duplication of other research and monitoring activities and requires the NOAA administrator to develop a plan for the coordination of projects and activities between the program and other similar state and federal programs and centers of excellence.82

Broader questions of coordination among restoration activities go beyond the RESTORE Act and may include, in addition to NRDA and NFWF activities, existing federal and state projects and activities, as well as activities conducted in other states that might have an effect in the Gulf Coast region. Some potential questions addressing coordination include the following:

- How are restoration plans and projects coordinated among implementing entities? Is there a need for a congressionally authorized mechanism for coordination?

- How are new restoration activities authorized under the RESTORE Act integrated with existing restoration programs and efforts, without causing overlap?

- Will there be assurances that project monitoring and oversight are measured with similar metrics? Will data and results from restoration activities be comparable to similar activities implemented by another entity?

- Will baseline ecosystem restoration activities continue under their authorities and funding or will they be integrated into efforts authorized under the RESTORE Act and other Deepwater Horizon-related restoration activities?

Planning

Another potential issue for Congress is the status and content of multiple planning processes related to Gulf restoration. Although the planning process and implementation progress under the RESTORE Act may receive significant attention from Congress, planning under the NFWF and NRDA processes may be of interest to some in Congress, as well.

As discussed previously, the Gulf Coast Ecosystem Restoration Council published a Comprehensive Plan Update in December 2016. The stated intent of the plan is to provide a framework to implement restoration activities in the Gulf Coast region. When it was published, the council noted that the updated plan was intended to "provide strategic guidance that will help the Council more effectively address these complex and critical challenges and supersedes the Initial Plan approved by the Council in August 2013."83

The Comprehensive Plan Update published by the council included some of the elements required by Congress that were not in the Initial Plan. Among these, it included a description of the process underpinning project selection and state expenditure plans, as well as congressionally required elements, such as the 10-Year Funding Strategy and the 3-year FPL. Additionally, other elements that are related to Gulf Coast restoration were not required by Congress to be included in the report. For instance, Congress did not require that the report cover the Direct Component under the RESTORE Act (i.e., funding which goes directly to states). Similarly, activities under the Gulf Coast Science Program and centers of excellence were not included in this plan.

The two other Gulf Coast restoration planning processes discussed herein are those coordinated by NFWF and NRDA trustees, respectively. Notably, neither is governed by RESTORE Act planning processes. NFWF restoration actions are governed first by the criminal settlements between DOJ and BP and DOJ and Transocean (and subsequent guidance from NFWF), whereas the NRDA planning process is governed by NOAA regulations, pursuant to the OPA. These planning processes may be more targeted than those under the RESTORE Act and are expected to proceed independently.

Another issue for Congress is whether the current approach to ecosystem restoration in the Gulf is effective and whether or not it would be better implemented under alternative organizational structures. For instance, in the Everglades, restoration is federally led and ostensibly guided by a centralized, "comprehensive" plan, known as the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan (CERP). Authorized in the Water Resources Development Act of 2000 (P.L. 106-541), CERP outlined 68 distinct projects that are intended to comprise a large amount of the restoration effort. Generally speaking, CERP is more centralized and detailed than the comprehensive planning process that has been carried out for the Gulf under the RESTORE Act to date. However, it is similar to the current planning process in the Gulf in that it is dependent on other restoration efforts that are not formally covered by CERP or led by the federal government.84 In the case of the Everglades, planning for these activities is coordinated by a separate congressionally authorized body, the South Florida Ecosystem Restoration Task Force.85 A complete comparison and assessment of the disparate planning processes in the Gulf is made difficult by the absence of some information from the processes. For instance, to date no plans have provided an estimated time frame for completing restoration, nor have the plans addressed the maintenance of restoration activities when funding has been exhausted and governance structures have been dissolved. The Comprehensive Plan Update discusses consideration of regional planning frameworks, with collaboration meetings and workshops to begin in 2017, but as of July 2017 no such documentation is available.86 Potential questions Congress may have related to planning for restoration may include the following:

- How is the planning process under the RESTORE Act incorporating other processes, such as those related to prespill restoration activities or restoration activities conducted by states and other entities such as NFWF or under NRDA?

- What is the anticipated time line for the implementation of the individual elements of the RESTORE Act?

- Will a vision or set of criteria for defining what a restored ecosystem will look like be created or required under RESTORE Act and other planning processes in the Gulf? Will it include an estimate of how long restoration will take or how much it will cost?

- Who will be responsible for providing future funding to continue restoration activities in the Gulf after activities funded under the Deepwater Horizon settlements are complete?

- In addition to the 3% limit on administrative expenditures, will there be limits for other expenditure types?

- What internal and external controls procedures or processes are overseeing Gulf Coast restoration planning, and how effective have they been?

Implementation

Implementation and governance of restoration activities in the Gulf is another important aspect of restoration that is still under development by various entities involved in the Gulf Coast. Several questions related to implementation of activities could be posed, including questions on the division of labor between federal and state activities, how progress will be measured, and the timing of activities going forward.

As discussed previously, restoration activities in the Gulf Region will be implemented by several federal, state, and nongovernmental entities under different structures. The RESTORE Act does not specify an overarching entity that would monitor and report on the implementation of all aspects of restoration. The council's responsibility appears to be focused on the implementation of the Comprehensive Plan and state plans pursuant to the Spill Impact Component, while NRDA and NFWF plans will focus on those elements separately.87 This could raise questions about how restoration activities derived from various funding streams relate to each other. For example,

- Will any entity be responsible for evaluating and reporting on the overall status of restoration activities in the Gulf, or will reporting be conducted separately?

- If restoration crosses state borders, will there be oversight to determine if restoration activities among states are complementary or contrasting?

- How will conflicting implementation objectives be handled among the various initiatives?

Monitoring the implementation and progress of all restoration activities and actions does not appear to be the objective of any one entity in this restoration initiative. The Gulf Coast Ecosystem Restoration Council is responsible for reporting on the progress of projects or programs to protect the Gulf Coast region under the Comprehensive Plan and State Plans, but it appears to have limited authorities over other activities. Two projects on the initial FPL include the Council Monitoring and Assessment Program and the Gulf of Mexico Alliance Monitoring Community of Practice.88 These projects would fund the development of Gulf region-wide monitoring, create a data management plan, and collaborate with other restoration entities.89 This could lead to questions such as the following:

- Is the council considered the overarching entity for measuring the progress of restoration based on all restoration actions or those just associated with the Comprehensive Plan? Does it have authorities that it is not using?

- Will the council be measuring the progress of individual projects and programs or addressing the overall, holistic view of restoration? What indicators and metrics are being used?

- When the fund is empty and the council is dissolved, who will be responsible for maintaining the restoration initiative or measuring its progress?

- Is adaptive management being used to evaluate and guide restoration actions?

- Is there a process or entity that could change the direction of restoration efforts, and would they have the authority to initiate and carry out holistic changes or just changes to individual projects and programs?

Balancing Goals

Restoration in the Gulf Coast is different from some other restoration initiatives around the nation, primarily because a considerable amount of funding is expected to be provided up front toward the dual objectives of restoring the ecosystem and the economic vitality of the Gulf Coast. Some in Congress might seek to weigh in on how efficiently funds are used to satisfy the dual goals of restoration and economic vitality, and may conduct oversight on balance of resources used for restoring the ecosystem versus restoring the economy of the region. Under the RESTORE Act and Treasury regulations, there are no formulas or provisions that address the exact balance of efforts to restore the ecosystem and the economy. Acknowledging that these two objectives are not mutually exclusive, preliminary questions could include the following:

- How will funding allocated from the Gulf Coast Restoration Trust Fund balance the dual goals of ecosystem restoration and economic restoration?

- Under state plans, will there be guidance on how funds should be split among economic and ecosystem-related projects?

- Is restoration funding derived from the trust fund intended to replace state funding for ecosystem restoration and economic vitality or add to existing restoration funding in state budgets?90

- The Comprehensive Plan Update contains seven objectives and notes that funding for these objectives will not be equally distributed.91 How will the funding be distributed? Are the objectives prioritized?

- Is the Comprehensive Plan Update prioritizing ecological activities over economic activities?

- Will the concept of ecosystem services be used to determine the priority of projects to be implemented? If so, how will the assessment of ecosystem services be conducted?

Concluding Remarks

Although implementation has progressed on several fronts, several aspects of Gulf Coast restoration planning, implementation, and funding are uncertain or still being developed. Some funding under the RESTORE Act, NFWF, and NRDA early restoration efforts has been released. Developments, such as the BP settlement, and the release of funding under NFWF, NRDA, and RESTORE Act processes, have increased the attention on Gulf Coast restoration. As the multiple processes governing these efforts move forward, Congress might consider questions related to their coordination, planning, and implementation and may look to other comparable initiatives for lessons learned that could be incorporated into work on the Gulf Coast. Questions aimed at addressing adaptive management, governance, and striking a balance between restoration and the economy could be among the issues raised in congressional oversight of Gulf Coast restoration.

Appendix. Sources of Funding and Ongoing Federal Efforts for Gulf Coast Restoration

Table A-1. Sources of Funding for Restoration in the Gulf Region

(includes established and potential sources; does not include allocations for non-restoration activities)

|

Source/Mechanism |

Status |

Amount and Uses for Restoration Activities |

|

Anadarko Civil Settlement |

Approved by the U.S. District Court in the Eastern District of Louisiana on November 20, 2015 |

$159.5 million, of which $128 million is to be made available pursuant to the RESTORE Act. |

|

BP Civil Settlement |

Approved by the U.S. District Court in the Eastern District of Louisiana on April 4, 2016 |

The civil claims total more than $20 billion. Over a 15-year period, BP will pay

BP also reached a separate agreement with the Gulf states to pay $4.9 billion, in total, to the five Gulf states and up to $1 billion to local governments. |

|

Transocean Civil Settlement |

Approved by the U.S. District Court in the Eastern District of Louisiana on February 14, 2013 |

$1 billion, of which 20% goes to the Oil Spill Liability Trust Fund and 80% ($800 million) goes into the Gulf Coast Restoration Trust Fund, to be divided as outlined under the RESTORE Act (P.L. 112-141, see "RESTORE Act/Gulf Coast Ecosystem Restoration Trust Fund" section):

|

|

Transocean Criminal Settlement |

Approved by the U.S. District Court in the Eastern District of Louisiana on February 14, 2013 |

$150 million to NFWF to support restoration efforts in the Gulf states related to the damages from the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. NFWF will allocate funding as follows:

|

|

MOEX Civil Settlement |

Approved by the U.S. District Court in the Eastern District of Louisiana on June 8, 2012 |

$25 million is to be distributed in various amounts among the five Gulf states for unspecified purposes. Supplemental environmental projects:

|

Source: Table compiled by CRS.

Table A-2. Ongoing Federal Ecosystem Restoration and Related Efforts in the Gulf

(selected federal coordination and funding efforts in the Gulf Coast region)

|

Initiative |

Description/Issue Addressed |

Agency Lead |

|

Louisiana Coastal Area Protection and Restoration Plan (LCAPR) |

Comprehensive ecosystem restoration and hurricane protection plan for Coastal Louisiana. |

Corps |

|

Louisiana Coastal Area Near-Term Plan (LCA) |

Projects to improve ecosystem function in coastal Louisiana, as well as other incidental benefits. Projects include beneficial use of dredged material, diversion of sediment and water, barrier island restoration, and coastal protection |

Corps |

|

Mississippi Area Coastal Improvement Program (MsCIP) |

Comprehensive planning to address hurricane/storm damage reduction, salt water intrusion, shoreline erosion, fish and wildlife preservation through restoration and flood control projects in coastal Mississippi. |

Corps |

|

Gulf Hypoxia Task Force |

Provides executive-level direction and support for coordinating the actions of 10 states and 5 federal agencies working on nutrient management within the Mississippi River and Gulf of Mexico watershed. |

EPA (chair) |

|

Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan (CERP) |

Federal/state framework to restore, protect, and preserve the water resources of central and southern Florida, including the Everglades. |

Corps/DOI |

|

National Ocean Council |

Coordinates federal stewardship efforts for oceans through support for regional planning bodies, including one such body for the Gulf of Mexico. |

CEQ/OSTP (co-chairs) |

|

National Estuary Program (NEP) |

Works to restore and maintain water quality and ecological integrity of estuaries of national significance. Seven of 18 NEPs are in the Gulf Region. |

EPA |

|

Gulf of Mexico Program/Gulf of Mexico Alliance |

Program to facilitate collaborative actions to protect, maintain, and restore health and productivity of the Gulf of Mexico. Made up of Gulf Coast governors and supported by 13 federal agencies. |

EPA (DOI, NOAA co-leads) |

|

Coastal Wetlands Planning Protection and Restoration Act (CWPPRA) |

Federal/state program that focuses on marsh creation, restoration, protection, and enhancement as well as barrier island restoration. CWPPRA has planned and designed several larger-scale projects, which may be constructed by other initiatives. |

FWS |

|

Coastal and Estuarine Land Conservation Program (CELCP) |

Provides matching funds to state and local governments to purchase significant coastal and estuarine lands from willing sellers. |

NOAA |

|

North American Wetlands Conservation Act (NAWCA) |

Provides matching grants to organizations and individuals that have developed partnerships to carry out wetlands conservation projects for the benefit of wetlands-associated migratory birds and other wildlife. |

FWS |

Sources: Table compiled by CRS from multiple sources, including U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Gulf of Mexico Regional Ecosystem Restoration Strategy and America's Gulf Coast: A Long-Term Recovery Plan after the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill (also referred to as the "Mabus Report").

Notes: List is illustrative of federal efforts only and does not include state-led efforts. List of federal efforts is not exhaustive. CEQ = White House Council on Environmental Quality; Corps = U.S. Army Corps of Engineers; DOI = U.S. Department of the Interior; EPA = U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; FWS = U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; NOAA = National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; OSTP = White House Office of Science and Technology Policy.