Introduction

Instability in Central America—particularly the "northern triangle" nations of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras—is one of the most pressing challenges for U.S. policy in the Western Hemisphere. These countries are struggling with widespread insecurity, fragile political and judicial systems, and high levels of poverty and unemployment. The inability of the northern triangle governments to address those challenges effectively has had far-reaching implications for the United States. Transnational criminal organizations have taken advantage of the situation, using the Central American corridor to traffic 90% of cocaine destined for the United States, among other illicit activities.1 The region also has become a significant source of mixed migration flows of asylum seekers and economic migrants to the United States.2 In FY2016, U.S. authorities at the southwestern border apprehended nearly 200,000 unauthorized migrants from the northern triangle; about 60% of those apprehended were unaccompanied minors or families, many of whom surrendered to law enforcement and requested humanitarian protection.3

The Obama Administration determined that it was "in the national security interests of the United States" to work with Central American governments to improve security, strengthen governance, and promote economic prosperity in the region.4 Accordingly, the Obama Administration launched a new, whole-of-government U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America and requested significant increases in foreign assistance to implement the strategy, primarily through the State Department and U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). Congress has appropriated $1.4 billion in aid for the region since FY2016 but has required the northern triangle governments to address a series of concerns prior to receiving U.S. support.

The Trump Administration has begun to adjust the Central America strategy as part of its broader reevaluation of U.S. foreign policy. Although Secretary of Homeland Security John Kelly has asserted that the "U.S. government is committed to working with ... partners in the region to address the underlying issues driving illegal migration from Central America," the Trump Administration has proposed a $195 million (30%) cut in funding for the Central America strategy in FY2018.5 Any shifts in funding priorities or levels, however, would have to be approved by Congress.

This report examines the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America, including its formulation, objectives, funding, and relationship to the Alliance for Prosperity plan put forward by the northern triangle governments. The report also analyzes several policy issues that the 115th Congress may assess as it considers the future of the Central America strategy. These issues include the funding levels and strategy necessary to meet U.S. objectives; the extent to which Central American governments are addressing their domestic challenges; the utility of conditions placed on assistance to the region; and how changes in U.S. immigration, trade, and drug control policies could impact conditions in the region.

|

|

Source: Congressional Research Service (CRS) Graphics. Notes: The "northern triangle" countries (El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras) are pictured in orange. |

U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America

Background and Formulation

Central America is a diverse region that includes the northern triangle nations of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras, which are facing acute economic, governance, and security challenges; the former British colony of Belize, which is stable politically but faces a difficult economic and security situation; Nicaragua, which has a relatively stable security situation but a de facto single-party government and high levels of poverty; and Costa Rica and Panama, which have comparatively prosperous economies and strong institutions but face growing security challenges (see Figure 1 and Table 1).6 Given the geographic proximity of the region, the United States historically has maintained close ties to Central America and played a prominent role in the region's political and economic development. It also has provided assistance to Central American nations designed to counter potential threats to the United States, ranging from Soviet influence during the Cold War to illicit narcotics today.

|

Population (2016 est.) |

Land Area |

Gross Domestic Product (GDP, 2016 est.) |

Leadership |

|||

|

Belize |

367,000 |

22,806 sq. km. |

|

Prime Minister Dean Barrow |

||

|

Costa Rica |

4.9 million |

51,060 sq. km. |

|

President Luis Guillermo Solís |

||

|

El Salvador |

6.3 million |

20,721 sq. km. |

|

President Salvador Sánchez Cerén |

||

|

Guatemala |

16.2 million |

107,159 sq. km. |

|

President Jimmy Morales |

||

|

Honduras |

8.2 million |

111,890 sq. km. |

|

President Juan Orlando Hernández |

||

|

Nicaragua |

6.2 million |

119,990 sq. km. |

|

President Daniel Ortega |

||

|

Panama |

4.0 million |

74,340 sq. km. |

|

President Juan Carlos Varela |

Sources: Population estimates from U.N. Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), 2016 Statistical Yearbook for Latin America and the Caribbean, 2017; land area data from Central Intelligence Agency, World Factbook, 2017; GDP estimates from International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Economic Outlook Database April 2017, April 12, 2017.

The U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America is the latest in a series of U.S. efforts over the past 15 years designed to produce sustained improvements in living conditions in the region. During the Administration of President George W. Bush, U.S. policy toward Central America primarily was focused on boosting economic growth through increased trade. The George W. Bush Administration negotiated the Dominican Republic-Central America-United States Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR) and the U.S.-Panama Free Trade Agreement.7 It also awarded Honduras, Nicaragua, and El Salvador $851 million of Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) aid intended to improve productivity and connect individuals to markets.8

U.S. policy toward Central America shifted significantly near the end of the George W. Bush Administration to address escalating levels of crime and violence in the region. The George W. Bush Administration launched a security assistance package for Mexico and Central America known as the Mérida Initiative in FY2008, and the Obama Administration rebranded the Central America portion of the aid package as the Central America Regional Security Initiative (CARSI) in FY2010. Congress appropriated nearly $1.2 billion in aid between FY2008 and FY2015 to provide Central American partners with equipment, training, and technical assistance to improve narcotics interdiction and disrupt criminal networks; strengthen the capacities of Central American law enforcement and justice sector institutions; and support community-based crime and violence prevention efforts in the region.9

By the beginning of President Obama's second term, the Administration had concluded that although the resources provided through MCC, CARSI, and other U.S. initiatives had "contributed to localized gains and proof-of-concept policy examples," they had "not yielded sustained, broad-based improvements" in Central America.10 As a result, the Obama Administration already had begun to develop a new strategy for U.S. policy in Central America when an unexpected surge of unaccompanied minors and families from the northern triangle began to arrive at the U.S. border in 2014. The new strategy was approved by the National Security Council in August 2014 and became technically binding on all U.S. agencies in September 2014.11

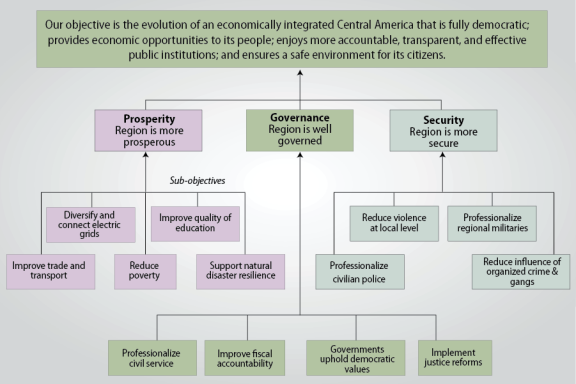

The U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America takes a broader, more comprehensive approach than previous U.S. initiatives in the region. Its stated objective is "the evolution of an economically integrated Central America that is fully democratic; provides economic opportunities to its people; enjoys more accountable, transparent, and effective institutions; and ensures a safe environment for its citizens."12 Whereas other U.S. efforts over the past 15 years generally emphasized a single objective, such as economic growth or crime reduction, the new strategy is based on the premise that prosperity, security, and governance are "mutually reinforcing and of equal importance."13

The new strategy also prioritizes interagency coordination more than previous initiatives. Many analysts criticized CARSI as a collection of "stove-piped" programs, with each U.S. agency implementing its own activities and pursuing its own objectives, which sometimes conflicted with those of other agencies, international donors, or regional partners.14 The U.S. Strategy for Engagement is designed as a whole-of-government effort that provides an overarching framework for all U.S. government interactions in Central America. While U.S. agencies continue to carry out a wide range of programs, the strategy is intended to ensure their efforts—and the messages they deliver to partners in the region—are coordinated. The strategy also seeks to combine U.S. resources with those of other donors and ensure that Central American governments are committed to carrying out complementary reforms.

Three Lines of Action

To achieve its objectives, the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America supports activities grouped under three overarching lines of action:

- 1. promoting prosperity and regional integration,

- 2. strengthening governance, and

- 3. improving security.

Promoting Prosperity and Regional Integration

With the exceptions of Costa Rica and Panama, the countries of Central America are among the poorest in the Western Hemisphere. Land ownership and economic power historically have been concentrated in the hands of a small group of elites, leaving behind a legacy of extreme inequality that has been exacerbated by gender discrimination and the social exclusion of ethnic minorities. Although the adoption of market-oriented economic policies in the 1980s and 1990s produced greater macroeconomic stability and facilitated the diversification of Central America's once predominantly agricultural economies, the economic gains have not translated into improved living conditions for many of the region's residents. Central America currently is undergoing a demographic transition in which the working age population, as a proportion of the total population, has grown significantly and is expected to continue growing in the coming decades. Although this transition presents a window of opportunity to boost economic growth, the region is failing to generate sufficient employment to absorb the growing labor supply (see Table 2).

|

Per Capita Income |

Poverty |

Economic Growth Rate |

Youth Disconnection |

||||||||

|

GDP per Capita (2016 estimates) |

% of Population Living in Poverty (2014) |

Annual % Growth in GDP (2016 estimate) |

% of Youth Aged 15-24 Who Neither Study Nor Work (2014) |

||||||||

|

Belize |

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Costa Rica |

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

El Salvador |

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Guatemala |

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Honduras |

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Nicaragua |

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Panama |

|

|

|

|

Sources: Per capita income and economic growth data from IMF, World Economic Outlook Database April 2017, April 12, 2017; poverty data from Statistical Institute of Belize and ECLAC, 2016 Statistical Yearbook for Latin America and the Caribbean, 2017; youth disconnection data from Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), Running Out of Tailwinds: Opportunities to Foster Inclusive Growth in Central America and the Dominican Republic, 2017.

Notes:

a. Poverty data for Belize and Nicaragua are from 2009.

The U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America seeks to address these challenges through a variety of actions designed to promote prosperity and regional integration. The strategy aims to facilitate increased trade by helping the region take advantage of the opportunities provided by CAFTA-DR and other trade agreements. For example, USAID seeks to strengthen the capacities of regional organizations, including the Central America Integration System,15 to analyze, formulate, and implement regional trade policies.16 Likewise, the Department of Commerce is providing training and technical assistance intended to improve customs and border management and facilitate trade.17

The strategy also seeks to diversify and connect electric grids in Central America to bring down the region's high electricity costs, which are a drag on economic growth. For example, the State Department's Bureau of Energy Resources aims to strengthen the Central American power market and regional transmission system and to enhance sustainable energy financing mechanisms to increase energy trade and attract investment in energy infrastructure.18 Similarly, USAID is working with regional governments to develop uniform procurement processes and transmission rights as well as regulations to facilitate investment in renewable power generation projects.19

Other activities carried out under the Central America strategy aim to reduce poverty in the region and to help those living below the poverty line meet their basic needs. In Honduras, for example, USAID supports a multifaceted food security program designed to reduce extreme poverty and chronic malnutrition by helping subsistence farmers diversify their crops and increase household incomes. The program is introducing farmers to new crops, technologies, and sanitary processes intended to increase agricultural productivity, improve farming practices and natural resource management, and enable farmers to enter into business relationships and export their products.20

Facilitating access to quality education is another way in which the strategy seeks to promote prosperity in Central America. For example, USAID funds basic education programs in Nicaragua, including efforts to improve teacher training and student reading performance.21 In El Salvador, USAID seeks to develop partnerships between academia and the private sector and to better link tertiary education with labor-market needs. Among other activities, USAID is providing support for career centers, internship programs, and academic programs in priority economic sectors.22

Finally, the Central America strategy seeks to build resiliency to external shocks, such as the drought and coffee fungus outbreak that have devastated rural communities in recent years. For instance, USAID is working with communities in the Western Highlands of Guatemala to reduce the region's vulnerability to climate change. USAID supports efforts to increase access to climate information to inform community decisions, strengthen government capacity to address climate risks, and disseminate agricultural practices that are resilient to climate impacts.23

Strengthening Governance

A legacy of conflict and authoritarian rule has inhibited the development of strong democratic institutions in most of Central America. The countries of the region, with the exception of Costa Rica and Belize, did not establish their current civilian democratic regimes until the 1980s and 1990s, after decades of political repression and protracted civil conflicts.24 Although every Central American country now holds regular elections, other elements of democracy, such as the separation of powers, remain only partially institutionalized. Moreover, failures to reform and dedicate sufficient resources to the public sector have left many Central American governments weak and susceptible to corruption. As governments in the region have become embroiled in scandals and have struggled to address citizens' concerns effectively, popular support for democracy has declined (see Table 3).

The U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America seeks to strengthen governance in the region in a variety of ways. It calls for the professionalization of Central American civil services to improve the technical competence of government employees, depoliticize government institutions, and ensure continuity across administrations. In El Salvador, for example, USAID is supporting civil society efforts to advocate for civil service reforms and the implementation of merit-based systems.25

|

Political Rights and Civil Liberties |

Government Effectiveness |

Public-Sector Corruption |

Satisfaction with Democracy |

|||||

|

Freedom House Score and Classification; 0-100, Least Free to Most Free (2017) |

Percentile Rank Globally; 0-100, Least Effective to Most Effective (2015) |

Perceptions; 0-100, Highly Corrupt to Very Clean (2016) |

% of Population Satisfied with How Democracy Functions in Their Country (2016) |

|||||

|

Belize |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Costa Rica |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

El Salvador |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Guatemala |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Honduras |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Nicaragua |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Panama |

|

|

|

|

Sources: Political rights and civil liberties data from Freedom House, Freedom in the World 2017, 2017; government effectiveness data from World Bank, Worldwide Governance Indicators, 2015; public sector corruption data from Transparency International, Corruption Perceptions Index 2016, January 25, 2017; satisfaction with democracy data from Corporación Latinobarómetro, Informe 2016, 2016.

The strategy also seeks to improve Central American governments' capacities to raise revenues while ensuring public resources are managed responsibly. For example, the Treasury Department is providing technical assistance to Guatemala's Ministry of Finance intended to improve treasury management operations and develop an investment policy to ensure financial resources are used efficiently and transparently.26 At the same time, USAID is training Guatemalan civil society organizations about transparency laws to strengthen the organizations' capacities to hold the government accountable.27

Other activities are designed to ensure partner governments uphold democratic values and practices, including respect for human rights. In Nicaragua, for example, USAID assisted civil society organizations that observed and documented the 2016 electoral process.28 The State Department's Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor (DRL) works throughout the region to support human rights defenders and civil society organizations that face threats and attacks as a result of their work. DRL assistance helps individuals avoid or mitigate threats, withstand attacks, and continue advocacy efforts domestically and internationally.29

Finally, the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America seeks to improve governance in the region by advancing justice sector reforms designed to decrease impunity. The State Department's Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (INL) is providing training and technical assistance to prosecutors, judges, and other justice sector actors on issues such as case management and justice sector administration. INL also is providing specialized training and equipment designed to strengthen forensic capabilities, internal affairs offices, and investigative skills in the region. Moreover, INL is partially funding the operations of the U.N.-backed International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG by its Spanish acronym) and the Organization of American States (OAS)-backed Mission to Support the Fight against Corruption and Impunity in Honduras (MACCIH by its Spanish acronym), which assist Guatemalan and Honduran efforts to investigate and prosecute complex cases.30

Improving Security

Security conditions in Central America have deteriorated significantly over the past 15 years. Violence has long plagued the region, and Belize, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras now have some of the highest homicide rates in the world. Common crime is also widespread. A number of interrelated factors have contributed to the poor security situation, including high levels of poverty, fragmented families, and a lack of legitimate employment opportunities, which leave many youth in the region susceptible to recruitment by gangs or other criminal organizations. In addition, the region serves as an important drug-trafficking corridor as a result of its location between cocaine-producing countries in South America and consumers in the United States. Heavily armed and well-financed transnational criminal organizations have sought to secure trafficking routes through Central America by battling one another and local affiliates and seeking to intimidate and infiltrate government institutions. Security forces and other justice sector institutions in the region generally lack the personnel, equipment, and training necessary to respond to these threats and have struggled with systemic corruption. As a result, most crimes are committed with impunity (see Table 4).

The U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America aims to improve security in the region in a number of ways, including through the professionalization of civilian police forces. For example, INL is carrying out a number of activities designed to improve the quality and strengthen the capacity of the Honduran National Police. Among other activities, INL is supporting efforts to vet police officers, improve police academy curricula and training, and enhance police engagement with civil society.31 U.S. assistance also has funded regional efforts to employ intelligence-led policing, such as the integration of the comparative statistics (COMPSTAT) model, which allows real-time mapping and analysis of criminal activity—in each of Panama's police zones.32

|

Homicide Rate |

Crime Victimization |

Rule of Law |

|||||

|

Murders per 100,000 Residents (2016) |

% of Population Reporting They or a Family Member Had Been the Victim of a Crime in the Past Year (2016) |

Percentile Rank Globally; 0-100, Weakest to Strongest (2015) |

|||||

|

Belize |

|

|

|

||||

|

Costa Rica |

|

|

|

||||

|

El Salvador |

|

|

|

||||

|

Guatemala |

|

|

|

||||

|

Honduras |

|

|

|

||||

|

Nicaragua |

|

|

|

||||

|

Panama |

|

|

|

Sources: Homicide rates from David Gagne, "2016 Homicide Rates in Latin America and the Caribbean," Insight Crime, January 16, 2017, and Benjamin Flowers, "Murders Up at the End of 2016," The Reporter (Belize), January 12, 2017; crime victimization data from Corporación Latinobarómetro, Informe 2016, 2016; rule-of-law data from World Bank, Worldwide Governance Indicators, 2015.

The strategy also expands crime and violence prevention efforts. USAID and INL have adopted a "place-based" approach that integrates their respective prevention and law enforcement interventions in the most violent Central American communities. USAID interventions include primary prevention programs that work with communities to create safe spaces for families and young people, secondary prevention programs that identify the youth most at risk of engaging in violent behavior and provide them and their families with behavior-change counseling, and tertiary prevention programs that seek to reintegrate juvenile offenders into society.33 INL interventions include primary prevention programs working to reduce gang affiliation and increase job prospects for inmates who are eligible for early release and the development of "model police precincts," which are designed to build local confidence in law enforcement by converting police forces into more community-based, service-oriented organizations.34

The U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America also continues long-standing U.S. assistance designed to professionalize regional armed forces. The strategy aims to encourage Central American militaries to transition out of internal law enforcement roles, strengthen regional defense cooperation, and enhance respect for human rights and civilian control of the military.35 U.S. support for regional militaries also is designed to increase their capabilities and strengthen military-to-military relationships. For example, some Central American armed forces personnel are receiving English language, patrol craft maintenance, and aircraft technical training at military institutions in the United States.36

In addition, the strategy seeks to reduce the influence of organized crime and gangs. Some U.S. assistance is designed to extend the reach of the region's security forces. For example, the U.S. government is providing Costa Rica with several patrol ships, planes, and other equipment, as well as training and maintenance, to enhance the capabilities of Costa Rican security forces to effectively patrol national territory, waters, and air space.37 INL is using other U.S. assistance to maintain specialized law enforcement units that are vetted by, and work with, U.S. personnel to investigate and disrupt the operations of transnational gangs and organized crime networks.38

Congressional Funding and Conditions

Congress has appropriated $1.4 billion for efforts under the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America. This figure includes $750 million in FY2016 and $655 million in FY2017 (see Table 5).39 The Trump Administration has requested $460 million for the strategy in FY2018, which would be a 30% cut compared to FY2017 but still would be more than was provided to the region in the years preceding the launch of the new strategy. From FY2010 to FY2014, foreign assistance appropriations for Central America averaged $376 million.40

Table 5. Funding for the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America by Country: FY2016-FY2018

(appropriations in millions of current U.S. dollars)

|

|

FY2016 |

FY2017 (estimate) |

FY2018 |

% Change 2017-2018 |

|||||||

|

Belize |

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Costa Rica |

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

El Salvador |

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Guatemala |

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Honduras |

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Nicaragua |

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Panama |

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Central America Regional Security Initiative |

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Other Regional Assistance |

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Total |

|

|

|

|

Sources: U.S. Department of State, Congressional Budget Justification for Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs, Fiscal Year 2018, May 23, 2017; and the explanatory statement accompanying P.L. 115-31.

Notes: "Other Regional Assistance" includes assistance appropriated or requested for Central America as a whole through funding accounts such as the State Department's Western Hemisphere Regional program, USAID's Central America Regional program, and the Overseas Private Investment Corporation. Health assistance provided through USAID's Central America Regional program is not considered part of the strategy.

The vast majority of the aid appropriated for the new strategy has been allocated to El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. Congress has placed strict conditions on aid to those three countries, however, requiring the northern triangle governments to address a range of concerns to receive assistance (see "FY2016 Conditions" and "FY2017 Conditions," below). Due to those legislative requirements, delays in the budget process, and congressional holds, most FY2016 assistance did not begin to be delivered until early 2017.

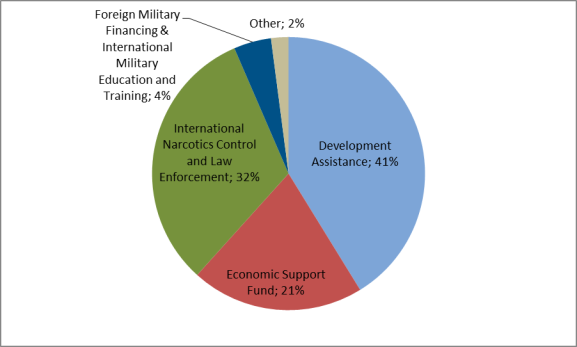

|

Figure 3. Funding for the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America by Foreign Assistance Account: FY2016 and FY2017 |

|

|

Source: CRS presentation of data from U.S. Department of State, Congressional Budget Justification for Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs, Fiscal Year 2018, May 23, 2017; and the explanatory statement accompanying P.L. 115-31, at https://www.congress.gov/crec/2017/05/03/CREC-2017-05-03-pt3-PgH3949-2.pdf. Notes: "Other" includes funding appropriated through the Global Health Programs account (1.9%); the Overseas Private Investment Corporation (0.1%); and the Nonproliferation, Antiterrorism, Demining, and Related programs account (0.1%). |

Although some of the activities supported by the Central America strategy are not new, higher levels of assistance have allowed the U.S. government to significantly scale up programs focused on prosperity and governance and to expand ongoing security efforts. For FY2016 and FY2017, Congress allocated funding for the Central America strategy in the following manner:

- 41% was appropriated through the Development Assistance account, which is designed to foster sustainable, broad-based economic progress and social stability by supporting long-term projects in areas such as democracy promotion, economic reform, agriculture, education, and environmental protection.

- 32% was appropriated through the International Narcotics Control and Law Enforcement account, with the funds roughly evenly divided between programs to support law enforcement and programs designed to strengthen other justice sector institutions.

- 21% was appropriated through the Economic Support Fund account, which funds USAID crime and violence prevention programs as well as efforts to promote economic reform and other more traditional development projects.

- 4% was appropriated through the Foreign Military Financing and International Military Education and Training accounts, which provide equipment and personnel training to regional militaries (see Figure 3).

To date, Congress has appropriated all funds for the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America to the State Department and USAID, with the exception of $2 million appropriated to the Overseas Private Investment Corporation in FY2016. Nevertheless, many other U.S. agencies are carrying out programs intended to advance the objectives of the strategy using their own resources and/or funds transferred from the State Department and USAID. The other agencies involved include the Department of Agriculture, the Department of Commerce, the Department of Defense, the Department of Homeland Security, the Department of Justice, the Department of Labor, the Department of the Treasury, the Inter-American Foundation, the Millennium Challenge Corporation, and the U.S. Trade and Development Agency.

FY2016 Conditions

In December 2015, Congress enacted the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2016 (P.L. 114-113). The act provided $750 million to begin implementing the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America but placed numerous conditions on aid for the three northern triangle governments.

The act stipulated that 25% of the "assistance for the central governments of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras" could not be obligated until the Secretary of State certified that each government was "taking effective steps" to

- inform its citizens of the dangers of the journey to the southwest border of the United States;

- combat human smuggling and trafficking;

- improve border security; and

- cooperate with U.S. government agencies and other governments in the region to facilitate the return, repatriation, and reintegration of illegal migrants arriving at the southwestern border of the United States who do not qualify as refugees consistent with international law.

The State Department issued certifications for all three northern triangle governments related to those conditions on March 10, 2016.41

The act also stipulated that another 50% of the "assistance for the central governments of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras" could not be obligated until the Secretary of State certified the governments were "taking effective steps" to

- establish an autonomous, publicly accountable entity to provide oversight of the [Alliance for Prosperity] plan;

- combat corruption, including investigating and prosecuting government officials credibly alleged to be corrupt;

- implement reforms, policies, and programs to improve transparency and strengthen public institutions, including increasing the capacity and independence of the judiciary and the Office of the Attorney General;

- establish and implement a policy that local communities, civil society organizations (including indigenous and marginalized groups), and local governments are to be consulted in the design and participate in the implementation and evaluation of activities of the [Alliance for Prosperity] plan that affect such communities, organizations, and governments;

- counter the activities of criminal gangs, drug traffickers, and organized crime;

- investigate and prosecute in the civilian justice system members of military and police forces who are credibly alleged to have violated human rights, and ensure that the military and police are cooperating in such cases;

- cooperate with commissions against impunity, as appropriate, and with regional human rights entities;

- support programs to reduce poverty, create jobs, and promote equitable economic growth in areas contributing to large numbers of migrants;

- establish and implement a plan to create a professional, accountable civilian police force and curtail the role of the military in internal policing;

- protect the right of political opposition parties, journalists, trade unionists, human rights defenders, and other civil society activists to operate without interference;

- increase government revenues, including by implementing tax reforms and strengthening customs agencies; and

- resolve commercial disputes, including the confiscation of real property, between United States entities and such government.

The State Department issued certifications related to those conditions for Guatemala on June 28, 2016; for El Salvador on August 29, 2016; and for Honduras on September 30, 2016.42

FY2017 Conditions

After a series of continuing resolutions, President Trump signed into law the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2017 (P.L. 115-31), on May 5, 2017. The act provided $655 million to continue implementation of the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America.

Congress also included a number of directives in the legislation. Within 90 days of enactment, the Secretary of State, in consultation with other relevant agencies, is required to review the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America and submit an updated strategy to the Senate Appropriations, Senate Foreign Relations, House Appropriations, and House Foreign Affairs Committees. Likewise, the explanatory statement accompanying the legislation directs the Secretary of State, in coordination with the USAID Administrator, to update the monitoring and evaluation plan for the strategy and submit a new plan to Congress by the end of the fiscal year. The plan is required to link specific programs to the strategy's objectives and subobjectives, to include performance indicators for each objective and subobjective, and to establish benchmarks and annual goals for each indicator.43

The act maintained the withholding requirements on aid for the northern triangle governments that were enacted in FY2016. However, Congress slightly altered the wording of some of the conditions.

The act stipulates that 25% of the "assistance for the central governments of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras" may not be obligated until the Secretary of State certifies that each government is "taking effective steps, which are in addition to those steps taken since the certification and report submitted during the prior year" to

- inform its citizens of the dangers of the journey to the southwest border of the United States;

- combat human smuggling and trafficking;

- improve border security, including to prevent illegal migration, human smuggling and trafficking, and trafficking of illicit drugs and other contraband; and

- cooperate with U.S. government agencies and other governments in the region to facilitate the return, repatriation, and reintegration of illegal migrants arriving at the southwest border of the United States who do not qualify for asylum, consistent with international law.

The act also stipulates that another 50% of the "assistance for the central governments of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras" may not be obligated until the Secretary of State certifies that each government is "taking effective steps, which are in addition to the steps taken since the certification and report submitted during the prior year" to

- work cooperatively with an autonomous, publicly accountable entity to provide oversight of the [Alliance for Prosperity] plan;

- combat corruption, including investigating and prosecuting current and former government officials credibly alleged to be corrupt;

- implement reforms, policies, and programs to improve transparency and strengthen public institutions, including increasing the capacity and independence of the judiciary and the Office of the Attorney General;

- implement a policy to ensure that local communities, civil society organizations (including indigenous and other marginalized groups), and local governments are consulted in the design, and participate in the implementation and evaluation of, activities of the [Alliance for Prosperity] plan that affect such communities, organizations, and governments;

- counter the activities of criminal gangs, drug traffickers, and organized crime;

- investigate and prosecute in the civilian justice system government personnel, including military and police personnel, who are credibly alleged to have violated human rights, and ensure that such personnel are cooperating in such cases;

- cooperate with commissions against corruption and impunity and with regional human rights entities;

- support programs to reduce poverty, expand education and vocational training for at-risk youth, create jobs, and promote equitable economic growth, particularly in areas contributing to large numbers of migrants;

- implement a plan that includes goals, benchmarks and timelines to create a professional, accountable civilian police force and end the role of the military in internal policing, and make such plan available to the Department of State;

- protect the right of political opposition parties, journalists, trade unionists, human rights defenders, and other civil society activists to operate without interference;

- increase government revenues, including by implementing tax reforms and strengthening customs agencies; and

- resolve commercial disputes, including the confiscation of real property, between United States entities and such government.

The State Department has not yet issued certifications for either set of conditions for any of the northern triangle governments.

Relationship to the Alliance for Prosperity

Many observers have confused the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America with the Plan of the Alliance for Prosperity in the Northern Triangle, which was announced by the Salvadoran, Guatemalan, and Honduran governments in September 2014. Drafted with technical assistance from the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), the five-year, $22 billion initiative aims to accelerate structural changes in the northern triangle that would create incentives for people to remain in their own countries. It includes four primary objectives and strategic actions to achieve them:

- 1. Stimulate the productive sector, by supporting strategic sectors (such as textiles, agro-industry, light manufacturing, and tourism); creating special economic zones to attract new investment; modernizing and expanding infrastructure; deepening regional trade and energy integration; and supporting the development of micro, small, and medium enterprises and their integration into regional production chains.

- 2. Develop human capital, by improving access to, and the quality of, education and vocational training; expanding access to health care and adequate nutrition; expanding social protection systems, including conditional cash transfer programs for the most vulnerable; and strengthening protection and reintegration mechanisms for migrants.

- 3. Improve public safety and access to justice, by investing in violence prevention programs; ensuring schools are safe spaces; furthering the professionalization of the police, including through the adoption of community policing practices; enhancing the capacity of investigators and prosecutors; and strengthening prison systems.

- 4. Strengthen institutions and promote transparency, by improving tax administration and revenue collection; professionalizing human resources; strengthening government procurement processes; and increasing budget transparency and access to public information.44

The northern triangle governments budgeted more than $2.8 billion for the Alliance for Prosperity in 2016, which was the first official year of implementation (see Table 6). The resources allocated to the plan included government revenues as well as loans from the IDB and other international financial institutions. About 47% of the funding was dedicated to stimulating the productive sector, 42% to developing human capital, 10% to improving public safety, and 1% to strengthening institutions.

|

Goal |

El Salvador |

Guatemala |

Honduras |

Total |

||||

|

Stimulate Productive Sector |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Develop Human Capital |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Improve Public Safety |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Strengthen Institutions |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Total |

|

|

|

|

Source: Data from the Inter-American Development Bank, May 2017.

The Obama Administration praised the northern triangle governments for developing the Alliance for Prosperity and committed to working to align U.S. programs and resources with the strategic priorities identified under the initiative.45 Congress also expressed support for the initiative and appropriated funds to implement the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America "in support of the Plan of the Alliance for Prosperity in the Northern Triangle" in the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2016 (P.L. 114-113). Nevertheless, the Alliance for Prosperity and the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America remain separate initiatives.

Although the two initiatives have broadly similar objectives and fund complementary efforts, they prioritize different activities since the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America is designed to advance U.S. interests in all seven nations of the isthmus and the Alliance for Prosperity represents the agendas of the three northern triangle governments. For example, the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America devotes significant funding to efforts intended to strengthen the capacity of civil society groups, which—to date—have played relatively minor roles in the Alliance for Prosperity. Similarly, the Alliance for Prosperity has focused heavily on large-scale infrastructure projects and conditional cash transfer programs, which are not funded by the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America.46

Policy Issues for Congress

Congress may examine a number of policy issues as it deliberates on potential changes to the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America and future appropriations for the initiative. These issues include the funding levels and strategy necessary to meet U.S. objectives in the region, the extent to which Central American governments are demonstrating the political will to undertake domestic reforms, the utility of the conditions placed on assistance to Central America, and the potential implications of changes to U.S. immigration, trade, and drug control policies for U.S. objectives in the region.

Strategy and Funding Levels

Congress and the Trump Administration have begun to reassess U.S. policy in Central America. Although most of the funding for the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America only began to be delivered in early 2017, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2017 (P.L. 115-31) directs the Secretary of State to review and update the strategy within 90 days of enactment. The Trump Administration may begin to flesh out its updated strategy at the Conference on Prosperity and Security in Central America, which is scheduled to be held in Miami on June 15-16, 2017.47

The Trump Administration's FY2018 budget request suggests that the Administration intends to reduce U.S. involvement in Central America while shifting toward a more security-oriented approach. As noted previously, the Administration has requested $460 million in assistance for Central America in FY2018, which is $195 million (30%) less than the FY2017 estimate and $290 million (39%) less than the FY2016 level. All types of assistance would decline under the request; however, development assistance would decline the most in terms of absolute dollars (see Table 7 below).

- The request would provide Central American nations with $189.5 million of bilateral development assistance intended to improve prosperity and governance in the region through a new Economic Support and Development Fund (ESDF) foreign assistance account. This amount would be $90 million (32%) less than the estimated amount provided through the Development Assistance account for the same types of aid programs in FY2017.48

- The request would provide $263.2 million for the Central America Regional Security Initiative (CARSI), including $101.4 million through the ESDF account and $161.8 million through the International Narcotics Control and Law Enforcement (INCLE) account. This amount would be $66 million (20%) less than the FY2017 estimate for CARSI.

- The request would provide $3.8 million in International Military Education and Training (IMET) assistance to Central America, which is $290,000 (2.5%) less than the FY2017 estimate. The request also would zero out Foreign Military Financing (FMF) assistance for Central America, which totaled $28.6 million in FY2017. Nevertheless, countries in the region potentially could receive some FMF assistance, either as loans or grants, through a proposed global fund.

Table 7. FY2018 Request for the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America by Foreign Assistance Account

(in millions of current U.S. dollars)

|

ESDF |

GHP |

INCLE |

NADR |

IMET |

FMF |

Total |

|||||||||||||||

|

Belize |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

Costa Rica |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

El Salvador |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

Guatemala |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

Honduras |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

Nicaragua |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

Panama |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

CARSI |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

Total |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: U.S. Department of State, Congressional Budget Justification for Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs, Fiscal Year 2018, May 23, 2017.

Notes: ESDF = Economic Support and Development Fund; GHP = Global Health Programs; INCLE = International Narcotics Control and Law Enforcement; NADR = Nonproliferation, Antiterrorism, Demining, and Related programs; IMET = International Military Education and Training; FMF = Foreign Military Financing; CARSI = Central America Regional Security Initiative.

Although the Administration's budget proposal would maintain support for a variety of assistance programs in Central America, it appears to move away from the underlying premise of the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America that prosperity, security, and governance are "mutually reinforcing and of equal importance."49 Under the request, CARSI would account for 57% of the funding for the Central America strategy, up from 50% in FY2017 and 46% in FY2016.50 By reducing assistance and shifting the balance toward security programs,51 the Trump Administration would effectively reestablish the U.S. policy approach that was in effect in the years preceding the adoption of the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America. That approach failed to generate sustained improvements in the region, however, as noted in 2015 by then-Assistant Secretary of State for Western Hemisphere Affairs Roberta Jacobson:

Over the past five years of implementing our Central America Regional Security Initiative, we've learned a great deal about what works and what doesn't work on security in Central America.... What we learned most of all was that unless we focus on improving the ability of governments to deliver services efficiently and accountably, and improve economic opportunities, especially for young people, as integral parts of security, nothing we do to make things safer will be sustainable.52

Many analysts still think that a comprehensive strategy that addresses economic and governance concerns in addition to security challenges is needed to improve conditions in Central America and ultimately reduce irregular migration and illicit trafficking from the region.53 Moreover, they maintain that steep cutbacks in assistance could lead Central Americans to question the commitment of the United States and undermine the individuals who are pushing for reforms in the region. Members of Congress who agree with those assessments could seek to maintain elevated appropriations levels for Central America or try to spread cuts more evenly across economic, governance, and security programs. Members also could consider a multiyear foreign assistance authorization for Central America to guide aid levels and priorities and reassure partners in the region that the United States is committed to a long-term effort.

Political Will in Central America

Although many analysts assert that Central American nations will require external support to address their challenges, they also contend that significant improvements in the region ultimately will depend on Central American leaders carrying out substantial internal reforms.54 That contention is supported by multiple studies conducted over the past decade, which have found that aid recipients' domestic political institutions play a crucial role in determining the relative effectiveness of foreign aid.55 Some scholars argue that this conclusion is also supported by the region's history:

How did Costa Rica do so much better by its citizens than its four northern neighbors since 1950? The answer, we contend, stems from the political will of Costa Rican leaders. Even though they shared the same disadvantageous economic context of the rest of Central America, Costa Rica's leaders adopted and kept democracy, abolished the armed forces, moderated income inequality, and invested in education and health over the long haul. The leaders of the other nations did not make these choices, at least not consistently enough to do the job.56

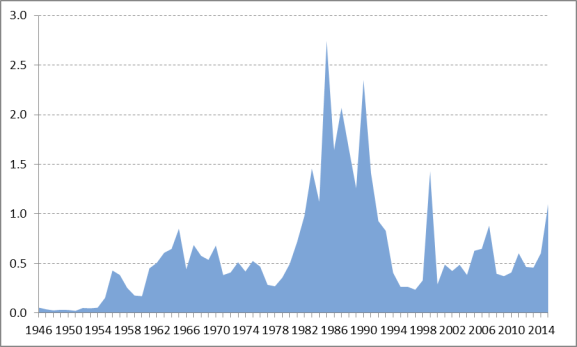

One of the underlying assumptions of the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America is that "Central American governments will continue to demonstrate leadership and contribute significant resources to address challenges" if they are supported by international partners.57 Such political will cannot be taken for granted, however, given that previous U.S. efforts to ramp up assistance to Central America—including substantial increases in development aid during the 1960s under President John F. Kennedy's Alliance for Progress and massive aid flows in the 1980s during the Central American conflicts (see Figure 4)—were not always matched by far-reaching domestic reforms in the region.58

|

Figure 4. U.S. Assistance to Central America: FY1946-FY2015 (obligations in billions of constant 2015 U.S. dollars) |

|

|

Source: CRS presentation of data from USAID, U.S. Overseas Loans and Grants: Obligations and Loan Authorizations, July 1, 1945-September 30, 2015, January 10, 2017, at https://explorer.usaid.gov/reports.html. Note: Includes aid obligations from all U.S. government agencies. |

Over the past few years, Central American governments have demonstrated varying levels of commitment to internal reform. As noted previously, the three northern triangle governments worked together to develop the Alliance for Prosperity, which includes numerous policy commitments. They already have implemented some legislative reforms and identified resources to advance the plan's objectives. Among other actions, El Salvador has begun to implement a comprehensive security plan; Guatemala has adopted reforms to improve the transparency of the national tax agency, including the creation of a new internal affairs unit; and Honduras has begun to restructure the police force, dismissing more than half of the top officers and developing new training and evaluation protocols.59 At the same time, tax collection has remained relatively flat in the region, inhibiting the governments' abilities to invest additional resources in key institutions and programs.60

Central American nations also have begun to combat systemic corruption. Attorneys general in all three northern triangle countries, with the backing of CICIG in Guatemala and MACCIH in Honduras, have taken on high-profile cases that have implicated presidents, Cabinet ministers, legislators, and members of the security forces. In Guatemala, for example, investigations into a corruption ring at the national tax agency led to the arrests of dozens of officials, including then-President Otto Pérez Molina. Nevertheless, many elected officials in the region have supported these types of anticorruption efforts only reluctantly. In Honduras, for example, President Juan Orlando Hernández established MACCIH in an attempt to mollify protestors after reports circulated that $330 million was embezzled from the Honduran social security institute and that some of the stolen funds were used to fund Hernández's 2013 election campaign. Hernández refused to grant MACCIH independent investigative or prosecutorial powers like those of CICIG, and the Honduran Congress has repeatedly delayed and modified MACCIH's proposed reforms.61

Congress could consider a number of actions to support reform efforts in the region. In addition to placing legislative conditions on aid, which is discussed in the following section (see "Aid Conditionality"), Congress could continue to offer vocal and financial support to individuals and institutions committed to change. For example, the House adopted a resolution (H.Res. 145, Torres) on May 17, 2017, that recognizes the anticorruption efforts of CICIG, MACCIH, and the attorneys general of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras, and calls on the northern triangle governments to provide the attorneys general with the support, resources, and independence they need to carry out their responsibilities. Similarly, the explanatory statement accompanying the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2017 (P.L. 115-31), stipulates that the funding appropriated for the Central America strategy includes $10.5 million for the Office of the Attorney General of El Salvador, $11 million for the Office of the Attorney General of Guatemala, $6.5 million for the Office of the Attorney General of Honduras, $6 million for CICIG, and $5 million for MACCIH.

Alternatively, Congress could call attention to individuals in the region who seek to subvert reform efforts, either by enacting legislation that focuses on their activities and establishes a new economic sanctions regime or by recommending sanctions pursuant to existing law. The Global Magnitsky Human Rights Accountability Act, adopted as part of the FY2017 National Defense Authorization Act (P.L. 114-328), for example, directs the President to consider information provided jointly by the majority and ranking leadership of the Senate Banking, Senate Foreign Relations, House Financial Services, and House Foreign Affairs Committees when determining whether to impose economic sanctions on, or to deny entry into the United States to, foreign individuals responsible for gross violations of human rights or significant corruption.62

Aid Conditionality

Congress has placed strict conditions on assistance to Central America in an attempt to bolster political will in the region and ensure foreign aid is used as effectively as possible. As noted previously, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2016 (P.L. 114-113), required the State Department to withhold 75% of "assistance for the central governments of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras" until the Secretary of State could certify those governments were "taking effective steps" to address a variety of issues. The act linked 25% of the withheld aid to efforts to improve border security, combat human smuggling and trafficking, inform citizens of the dangers of the journey to the United States, and cooperate with the U.S. government on repatriation. It linked the remaining 50% to 12 other issues, including efforts to combat corruption, increase revenues, and address human rights concerns (see "FY2016 Conditions" for the full list of conditions). The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2017 (P.L. 115-31), included similar conditions (see "FY2017 Conditions"), and some Members of Congress have called for maintaining the conditions in FY2018.

Although U.S. officials acknowledge that aid restrictions give them leverage with partner governments, many argue that the FY2016 and FY2017 appropriations measures included too many conditions and withheld too much aid. They contend that it is important to focus on a few key issues given the limited capacities of the northern triangle governments and that such prioritization is difficult with 16 different conditions. They also assert that it requires significant time to track efforts to meet the conditions and that those resources could be better used overseeing implementation of the Central America strategy.

U.S. officials argue that by subjecting nearly all "assistance for the central governments" to the withholding requirements, Congress effectively prevents U.S. agencies from carrying out some programs that would help the governments meet the conditions. For example, U.S. assistance to support police reform efforts in FY2016 had to be withheld until the State Department could certify that the northern triangle governments were taking effective steps to "establish and implement a plan to create a professional, accountable civilian police force and curtail the role of the military in internal policing." Similarly, U.S. assistance to strengthen tax collection agencies had to be withheld until the State Department could certify that the northern triangle governments were taking effective steps to "increase government revenues, including by implementing tax reforms and strengthening customs agencies." Congress could prevent such unintended consequences in the future by adding legislative language to waive withholding requirements for aid that would directly address the conditions themselves.

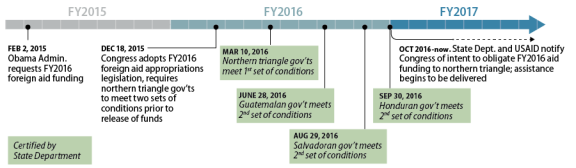

Withholding requirements also have delayed implementation of the Central America strategy. Although the FY2016 appropriations measure was enacted in December 2015, the State Department did not issue the final certification (for Honduras) until September 30, 2016—the last day of the fiscal year. As a result of the certification requirements, as well as delays in the budget process and congressional holds, most aid did not begin to be delivered until early 2017 (see Figure 5). U.S. agencies obligated some aid not subject to the withholding requirements at earlier dates, but they were hesitant to commit resources to specific activities until they knew whether they would have access to the remaining funding.

|

Figure 5. Central America Strategy Funding Timeline (status of FY2016 foreign assistance for the northern triangle) |

|

|

Source: CRS Graphics. |

At the same time, some Members of Congress and civil society organizations argue that the State Department was too quick to issue the certifications in FY2016. To date, most of the criticism has focused on the State Department's decision to certify that the Honduran government had met the second set of conditions, tied to 50% of the funds, which included several human rights requirements. The disagreement stems from the subjective wording of the legislation, which required the State Department to certify that the government was "taking effective steps" to

- investigate and prosecute in the civilian justice system members of military and police forces who are credibly alleged to have violated human rights, and ensure that the military and police are cooperating in such cases;

- cooperate with commissions against impunity, as appropriate, and with regional human rights entities; and

- protect the right of political opposition parties, journalists, trade unionists, human rights defenders, and other civil society activists to operate without interference.

In the memorandum of justification accompanying the certification, the State Department noted that an active duty Army Special Forces officer had been arrested and was facing prosecution in the civilian justice system for his alleged involvement in the murder of Berta Caceres, a high-profile indigenous and environmental activist. It also asserted that the public ministry was investigating dozens of high-level police officers, including some who allegedly were involved in the murders of top Honduran counternarcotics and anti-money laundering officials. With regard to cooperation with anti-impunity and human rights entities, the memorandum of justification noted that the Honduran government signed an agreement with the OAS to establish the MACCIH, invited the U.N. Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights to open an office in Honduras, and hosted multiple visits from special rapporteurs from the OAS and the United Nations. Finally, the memorandum of justification asserted that the Honduran government is implementing a 2015 law to protect human rights defenders, journalists, social communicators, and justice sector officials, and is dedicating additional resources and consulting with outside experts to improve the government's protection program.63

Critics argue that the human rights situation in Honduras remains poor despite those efforts and that the State Department's certification "makes a mockery" of the legislative conditions.64 Human rights groups note that political and social activists in Honduras continue to be killed, including numerous individuals who had been granted precautionary measures by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) and were supposed to be under government protection at the time they were murdered. The IACHR asserts that "no adequate or effective measures are being implemented to protect the beneficiaries of precautionary measures."65 The perpetrators of many of these attacks have yet to be identified.

Studies of aid conditionality have found that conditions generally fail to alter aid recipients' behavior when recipients think donors are unlikely to follow through on their threats to withhold aid.66 Members of Congress who are concerned that the State Department is issuing certifications too quickly and thereby weakening the conditions' effectiveness could seek changes to the certification process. The explanatory statement accompanying the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2017 (P.L. 115-31), for example, directs the Secretary of State to consult with the appropriations committees prior to submitting any certifications. Members who are not on the appropriations committees could push for additional changes in FY2018 that would require the northern triangle governments to meet specific criteria that could be measured objectively prior to receiving assistance.

Implications of Other U.S. Policy Changes

Given Central America's geographic proximity and close commercial and migration ties to the United States, changes in U.S. immigration, trade, and drug control policies can have far-reaching effects in the region. As Congress considers the future of the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America, it also may wish to evaluate how changes to other U.S. policies might support or hinder the strategy's objectives.

Immigration

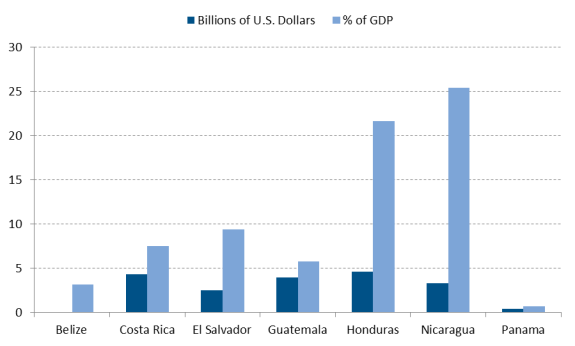

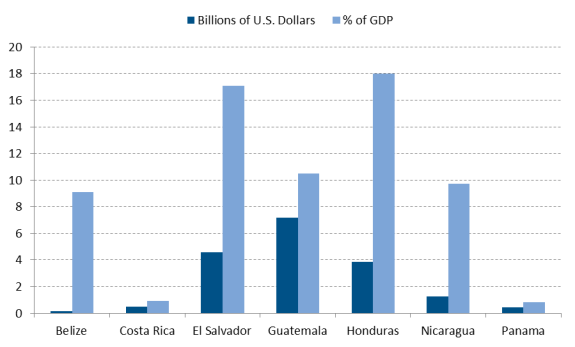

Central American nations have strong migration ties to the United States. In 2015, an estimated 3.4 million individuals born in Central America were living in the United States, including nearly 1.4 million Salvadorans; 928,000 Guatemalans; 599,000 Hondurans; and 256,000 Nicaraguans.67 Those immigrant populations play crucial roles in Central American economies. Remittances from Central American migrant workers abroad—the vast majority (78%) of whom live in the United States68—totaled nearly $18 billion in 2016, and were equivalent to 11% of GDP in Guatemala, 17% of GDP in El Salvador, and 18% of GDP in Honduras (see Figure 6). Many Central Americans reside in the United States in an unauthorized status, however, and are therefore at risk of being removed (deported) from the country. The Pew Research Center estimates that 1.7 million (more than half) of the Central Americans residing in the United States in 2014 were unauthorized migrants.69

Although Secretary of Homeland Security John Kelly has asserted that "there will be no mass deportations,"70 Central American officials are concerned that removals from the United States may accelerate as a result of President Trump's executive orders on immigration enforcement.71 They also are concerned that the Trump Administration may not extend Temporary Protected Status (TPS), which provides relief from removal for an estimated 2,600 Nicaraguans and 57,000 Hondurans who have lived in the United States since 1998 and 195,000 Salvadorans who have lived in the United States since 2001. TPS is scheduled to expire on January 5, 2018, for Nicaraguans and Hondurans and on March 9, 2018, for Salvadorans.72 In FY2016, the last full year of the Obama Administration, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) removed nearly 77,000 Central Americans, including about 34,000 Guatemalans; 22,000 Hondurans; and 21,000 Salvadorans.73 Some observers maintain that deportees could bring new skills back to their countries of origin.74 Nevertheless, a significant increase in removals from the United States likely would take a toll on Central American economies as a result of reduced remittances.75

|

|

Sources: CRS, using remittance data from Manuel Orozco, Remittances to Latin America and the Caribbean in 2016, Inter-American Dialogue, February 10, 2017; and Banco Central de Honduras, Memoria 2016, 2017; and GDP data from IMF, World Economic Outlook Database April 2017, April 12, 2017. |

In addition to the potential economic impact, increased deportations could fuel instability in the region. The northern triangle countries already are struggling to absorb deportees as a result of the countries' weak labor markets and lack of social services, and an increase in deportations likely would aggravate social tensions.76 Other Central American nations, such as Costa Rica, fear that stricter immigration enforcement in the United States could lead to higher levels of intraregional migration that would strain their government resources.77 Some Central American officials also assert that deportations from the United States are exacerbating security problems.78 Although U.S. deportations in the 1990s contributed to the spread of gang violence in Central America, many analysts argue that more recent deportations have had a minimal effect on security conditions in the region. In FY2016, fewer than 2,100 individuals removed by ICE were classified as suspected or confirmed gang members.79

Trade

Most Central American nations have close commercial ties to the United States and have become more integrated into U.S. supply chains since the adoption of CAFTA-DR. In 2016, U.S. merchandise trade with the seven nations of Central America amounted to nearly $47 billion. Although Central America accounts for a small portion (1.3%) of total U.S. trade, the United States is a major market for Central American goods.80 In 2016, the value of merchandise exports to the United States was equivalent to about 8% of GDP in Costa Rica, 9% of GDP in El Salvador, 22% of GDP in Honduras, and 25% of GDP in Nicaragua (see Figure 7).

Given the economic importance of access to the U.S. market, Central American nations have closely tracked recent developments in U.S. trade policy. Some in the region were relieved by President Trump's decision to withdraw from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a proposed trade agreement among 12 Asia-Pacific countries.81 Provisions of the agreement would have allowed nations such as Vietnam to export apparel to the United States duty-free, which could have eliminated much of the competitive advantage now enjoyed by Central American apparel producers as a result of CAFTA-DR.82 The Salvadoran government and the Central American-Dominican Republic Apparel and Textile Council estimated that the CAFTA-DR region would have experienced a 15%-18% contraction in industrial employment in the first year after the TPP was implemented.83 If the United States enters into a similar trade agreement in the future, Congress could consider granting Central American nations trade preferences equal to those included in the new agreement to ameliorate the shock to economies in the region.84

The Trump Administration's initial trade policy decisions, including withdrawing from TPP and proposing to renegotiate the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), have led some observers to question whether CAFTA-DR and the U.S.-Panama Free Trade Agreement also may be reviewed. Central American leaders think the agreements are unlikely to receive new scrutiny because the United States ran a trade surplus of $8.3 billion with Central America in 2016, including bilateral surpluses with every country but Nicaragua, and the Trump Administration has focused primarily on reducing U.S. trade deficits.85 Nevertheless, other potential changes to trade policy that the President has floated, such as imposing tariffs on imports, could be detrimental to Central American economies. The IDB estimates that if the United States increased the average tariff for imports from Central America by 20% of their value, the region's GDP would decline by 2.2-4.4 percentage points.86

Drug Control

Although illicit drug production and consumption remain relatively limited in Central America,87 the region is seriously affected by the drug trade as a result of its location between cocaine producers in South America and consumers in the United States. About 90% of cocaine trafficked to the United States in 2016 transited through Central America, along with unknown quantities of opiates, cannabis, and methamphetamine.88 The criminal groups that move cocaine through the region receive immense profits; in Honduras alone, trafficking is estimated to generate $700 million per year, which is equivalent to 3.3% of the country's GDP.89 Violence in the region has escalated as rival criminal organizations have fought for control over the lucrative drug trade and gangs have battled to control local distribution. The illicit funds produced by drug trafficking also have fostered corruption and impunity in Central America as criminal organizations have financed political campaigns and parties; distorted markets by channeling proceeds into legitimate and illegitimate businesses; and bribed security forces, prosecutors, and judges.90

Upon the launch of the Mérida Initiative in FY2008, the George W. Bush Administration pledged to reduce drug demand in the United States as part of its "shared responsibility" to address the challenges posed by transnational crime.91 The Obama Administration reiterated that pledge. Between FY2008 and FY2016, U.S. expenditures on drug demand reduction efforts increased from $8.6 billion to $11.3 billion and the portion of the U.S. drug control budget dedicated to demand reduction increased from $39% to 44%.92 The estimated number of individuals aged 12 or older currently using (past month use of) cocaine declined from about 2.1 million in 2007 to 1.4 million in 2011 before climbing back up to 1.9 million in 2015 (the most recent year for which data are available).93

Legislative measures to expand or improve the effectiveness of programs to reduce cocaine and other illicit drug consumption in the United States would complement efforts under the Central America strategy and would maintain the sense of "shared responsibility" that has guided U.S. relations with the region over the past decade. The 115th Congress could build on measures adopted during the 114th Congress to address substance abuse and treatment, including the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act (P.L. 114-198) and the 21st Century Cures Act (P.L. 114-255). The 115th Congress also will consider President Trump's FY2018 budget request, which includes $12.1 billion for treatment and prevention efforts, a 7% increase compared to FY2016, and $15.6 billion for supply reduction efforts, a 1% increase compared to FY2016.94

Outlook

Central America has made some progress in recent years but continues to face significant challenges. Although economic growth has accelerated since the end of the global financial crisis and U.S. recession, it has failed to produce enough employment to absorb the region's growing labor force or reduce poverty. Civil society has grown stronger, taking to the streets to demand government accountability, but anticorruption efforts have sparked a fierce backlash from those who benefit from the status quo. Violence has declined in several countries, yet the region continues to be one of the most violent in the world, with persistent human rights abuses and widespread impunity.

The United States has begun to implement a new U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America, with Congress appropriating $1.4 billion since FY2016 to promote prosperity, strengthen governance, and improve security in the region. Most analysts think it will be difficult to achieve those objectives, however, and living conditions in the region are unlikely to improve significantly in the short term. To achieve success in the medium and long term, Central American leaders would need to address long-standing issues such as weak institutions, precarious tax bases, and the lack of opportunities for young people, and international donors would need to provide extensive support over an extended period of time. Absent such efforts, conditions are likely to remain poor in several Central American countries, contributing to periodic instability that—as demonstrated by recent migrant flows—is likely to affect the United States.