Introduction

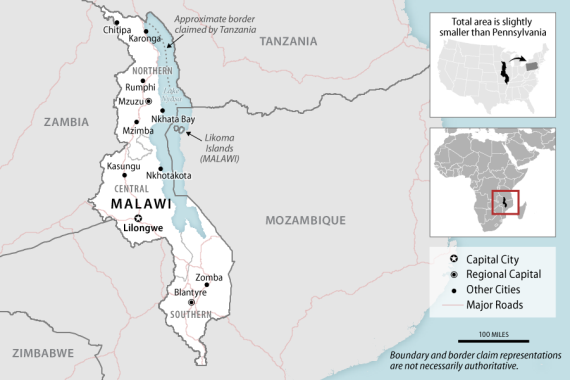

Malawi is a small, poor southeastern African country of just over 18 million people that in the early 1990s underwent a democratic transition from one-party rule. The country has long relied on foreign assistance, and U.S. aid is the main focus of U.S.-Malawian relations. Congressional interest centers mostly on such assistance, in particular health aid, as well as on concerns over governance trends, notably under the presidency of the late President Bingu wa Mutharika, the brother of incumbent President Peter Mutharika.1

In recent years, State Department and U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) bilateral assistance to Malawi has ranged between $196 million (FY2014) and $261 million (FY2016), supplemented in FY2016 with an additional $102.6 million in disaster response funding, primarily made up of food aid (see Table 1). The Obama Administration requested $195.6 million for FY2017. Under the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2017 (P.L. 115-31) congressional appropriators mandated that at least $56 million in Development Assistance account funds be allocated to Malawi, and that up to $10 million of this funding be made available for higher education programs. The Trump Administration requested $161.3 million for Malawi in FY2018. This reduction is part of a roughly one-third reduction in overall global aid levels proposed by the Trump Administration.2 Congress has yet to enact FY2018 foreign operations appropriations, but some Members have suggested that they are unlikely to enact many of the cuts proposed by the President.3

Malawi last held national elections in May 2014. Peter Mutharika garnered 36.4% of votes, a plurality that under Malawi's electoral system resulted in his victory over his reputed main political rival, then-incumbent President Joyce Banda. Banda had come to power after the death of President Wa Mutharika, who died in April 2012. Banda was serving as President Wa Mutharika's vice president at the time of his death, and constitutionally succeeded him. Reported efforts by then-Foreign Minister Peter Mutharika to prevent her succession led to treason charges against Mutharika during the Banda administration.4

Banda's tenure was initially well received by the international donor community, which had developed deep policy differences with Wa Mutharika (as discussed below), but the emergence of a corruption scandal during her administration tempered this view and led to European and multilateral donors to restrict aid; some of these restrictions remain in place.

Recent Key Developments

Drought. Like the rest of southern Africa, Malawi was affected by the 2015-2016 El Niño weather system. Drought conditions, exacerbated by delays in the distribution of state-subsidized seeds and fertilizer, resulted in poor harvests nationwide. USAID expects conditions to improve after the 2017 April-May harvest season. Nonetheless, further delays in fertilizer distributions, a worsening regional infestation of South American armyworms, and the inability of many farmers to hire agricultural laborers—a consequence of poor farm earnings in 2015-2016—are expected to result in continued low output and undercut incomes for poor rural dwellers.5 Roughly 6.7 million Malawians were experiencing acute food insecurity in early 2017.6

Territorial Dispute. Malawi and Tanzania have been engaged in a long-running dispute over competing sovereign claims to Lake Malawi (also known as Lake Nyasa), in part fueled by the prospect that it may contain deep-water fossil fuel reserves. The dispute reemerged in early 2016, when Malawi lodged a diplomatic protest with Tanzania's government after the latter published an official map showing the international border equally splitting the lake zone between the two countries. This depiction was at odds with Malawi's claim to the entire lake, based in part on mappings and the administrative history of the lake during the colonial period.

Regional mediation efforts, which had stalled in recent years, are being facilitated by Mozambique's former president, Joaquim Chissano. In February 2017, President Mutharika announced that mediation efforts would resume. Meanwhile, Malawi's government has allowed exploration for oil and gas in the lake to continue, drawing criticism from environmentalists and UNESCO. Some analysts contend that economic plans for the lake, which also include a shipbuilding plant, may remain stymied by uncertainty linked to the ongoing border dispute.7 In May 2017, the Malawian government announced that it would lodge a legal case over the dispute with the International Court of Justice in the Hague.8

Refugee Influx. Between late 2015 and April 2016, roughly 10,000 Mozambicans crossed into southern Malawi as refugees fleeing renewed fighting between the Mozambican government and an armed opposition party known as RENAMO. Most refugees have returned to Mozambique; roughly 3,000 remained in Malawi as of late March 2017. These refugees comprise a portion of a total population of about 27,300 refugees—most from Rwanda and Burundi—hosted by Malawi. Some have been living in Malawi for several years.9

|

Sources: Map created by CRS graphics team. Data from CIA, The World Factbook; International Monetary Fund World Economic Outlook database, October 2016; and World Bank, World Development Indicators database Notes: Estimates/data are for 2016 or current as of January 2017, unless otherwise specified. PPP stands for Purchasing Power Parity. PPP is expressed in international dollars, a hypothetical comparative unit that has the same purchasing power as a U.S. dollar has in the United States and is calculated based on factors including local costs for set baskets of goods, inflation, and exchange rates. These units are used to compare the purchasing value of U.S. dollars within a given domestic economy and others globally. |

Political Background10

Malawi, a former British colony, was ruled by its founding leader, Hastings Kamuzu Banda (no relation to Joyce Banda), from 1964 until he lost an election in 1994 to opposition leader Bakili Muluzi. That presidential election and the accompanying legislative races were the first multi-party elections held after a democratic transition spurred by social unrest and broad opposition to Kamuzu Banda's arguably authoritarian, patriarchal, and personalistic one-party rule. During Muluzi's two terms, political pluralism grew and market-based economic reforms took hold, as did allegations of corruption. Muluzi faced term limits and was succeeded in 2004 by Bingu wa Mutharika, whose first term was economically successful, but marred by increasing signs of a semi-authoritarian leadership style, which became more pronounced in his second term.11 He tried to expel Joyce Banda from her position as vice president, but she resisted and left Wa Mutharika's Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) to form her own People's Party (PP). The government harshly repressed mass protests in 2011, resulting in 20 deaths and about 500 arrests.

These developments prompted various international donors to withhold aid. In January 2011, the U.S. Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) paused implementation of its five-year, $350 million Compact in Malawi. In 2012, Wa Mutharika accused Western donors of falsely labeling him undemocratic and of aiding nongovernmental groups intent on ousting him, and said the donors should "go to hell."12 The MCC then suspended the Compact, which was reinstated after Wa Mutharika's death.

Presidency of Joyce Banda (2012-2014)

The Obama Administration and a number of Members of Congress expressed support for Banda in the months after she succeeded Wa Mutharika, citing what they viewed as her positive policy agenda and economic and governance decisions, several of which reversed several of her predecessor's most contentious actions.13 Banda, Africa's second female president (after Liberia's Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf), also won plaudits as an international advocate for women's rights; her tenure was seen as a sign of increasing gender equality in a region where male leaders have predominated. Her socioeconomic development and business experience also earned her a reputation as a leader with a personal commitment and the expertise necessary to advance equitable national growth and development, and as a model for other African leaders in this regard. Banda's administration drew high-level U.S. bilateral engagement, including meetings with President Obama and with Members of Congress. The MCC also reinstated its Compact after Banda took office.

After a brief political honeymoon, Banda faced criticism over various issues. Perhaps most important were her decisions to devalue the local currency, liberalize fuel prices, and pursue other internationally backed, market-based reforms. These resulted in economic hardship and multiple labor strikes; inflation rose and gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, already among the world's lowest, dropped from $347 (2011) to $223 (2013). Her administration's arrest of Peter Mutharika and several of his associates on treason charges in relation to their alleged attempts to engineer Mutharika's extra-constitutional succession of his late brother prompted protests. In 2013, Banda drew criticism over a state embezzlement scandal known as "Cashgate" (see below) and over the sale of a presidential jet, the proceeds of which were largely used to repay debts to an arms dealer and not to purchase food aid, as initially announced. These and other factors appear to have contributed to her electoral defeat in 2014.

2014 Election

The 2014 presidential race had been expected to be close. While then-President Banda enjoyed the advantages of incumbency, she also faced widespread criticism and an uphill electoral struggle linked to economic hardship and alleged corruption during her tenure. The polling process featured various logistical shortcomings, some violence, and legal challenges citing alleged Election Commission malfeasance and political interference in the electoral process. A key point of electoral controversy was an unsuccessful attempt by Banda to annul the election.14 In the end, Mutharika, garnered a winning 36.4% plurality of votes, defeating Banda, who came in third (with 20% of votes). All of the leading rival parties ultimately recognized his victory, as did the United States and international community.15

Legislative elections, held alongside the presidential vote, resulted in a hung parliament: two parties, including Mutharika's DPP, each hold roughly a quarter of seats, while independents hold another quarter. The remaining seats are held by Banda's PP and smaller parties. Mutharika has announced his intention to run for a second term in the next election, slated to be held in 2019.

Mutharika Administration

Mutharika took office in June 2014. His cabinet includes Finance and Economics Minister Goodall Gondwe, a long-time politician, government minister, and former International Monetary Fund (IMF) executive.16 It also includes a number of locally well-known politicians, including Minister of Lands, Housing, and Urban Development, Atupele Muluzi, the son of former President Muluzi.17 Mutharika has retained the defense portfolio.

Mutharika, born in 1940, is a former long-time U.S. resident and professor of law who held multiple teaching posts in the United States and Africa. He returned to Malawi for a period in 1993 to help design a new constitution underpinning the country's nascent multi-party political system. He left again, but returned in 2004, upon his brother's election as president. In 2009, Mutharika won a National Assembly seat as a candidate of his brother's DPP. He also held several cabinet ministerial posts in his brother's administration (Justice; Education, Science, and Technology; and later Foreign Affairs) and was a close presidential adviser.18

|

President Mutharika's Policy Agenda19 Mutharika's stated policy agenda centers on transparent and inclusive governance, a downsizing of government, and mixed public and private sector approaches to spurring economic growth. Upon taking office, he reduced the size of the cabinet from 25 to 18 ministers. He vowed to pursue a participatory, consultative governance style prioritizing socioeconomic development and inclusiveness, especially for women and youth. He began his tenure by pledging a zero tolerance policy for corruption and theft of public funds, promising to prosecute corrupt officials and ensure the independence of and adequate resources for the Anti-Corruption Bureau (ACB). The ACB has since regularly investigated and prosecuted alleged cases of public graft. In early 2015, the Mutharika administration launched the Public Finance Management Reforms Programme, which is designed to strengthen public sector finance management and prevent misuse of public funds.20 Allegations of government corruption persist, however, both petty and large-scale (see below). The Mutharika administration has launched a number of efforts to stimulate economic development through investment in infrastructure projects. Examples include the construction of roads linking urban markets to rural centers and the launching of a water transport project linking southern Malawi to a Mozambican ocean port via the Zambezi River. The administration is also endeavoring to increase electrical power capacity, a goal shared with prior administrations; develop a range of energy resources, such as renewables, biofuels, and fossil fuels; and reform and build the capacity of the power sector. The latter is a focus of U.S. support under Malawi's MCC Compact (see below). Mutharika has also created public-private partnerships in the power sector and in support of improved airport management, and is pursuing efforts to facilitate and protect private investment and increase the ease of doing business. He has enjoyed some success in this regard; under his tenure Malawi has jumped from 164th (2015) to 133rd (2017) in the World Bank's annual Doing Business index, with notable improvements in ensuring access to credit.21 Agricultural diversification is another priority. He has set out plans to promote pre-export value additions to tobacco (Malawi's main export), increase sugar exports, reform the tea sector, develop a paprika industry, and promote other crop commodities—as well as to increase food security and access to nutrition through enhancing the production of maize (the main staple food) and legumes for the domestic market. The government also supports a housing construction material subsidy program aimed at increasing access to affordable housing and boosting the construction industry. Greater development of tourism, a key source of hard currency, is another goal. |

Economic Overview22

Malawi's GDP fell from $6.4 billion in 2015 to $5.5 billion in 2016, owing to decreased agricultural production linked to the severe drought. GDP per capita—which is among the world's lowest—fell substantially, from $354 in 2015 to $294 last year.23 Analysts expect growth to pick up in 2017 with the end of the drought and recuperation of the agricultural sector: the IMF projects GDP growth to accelerate from 2.7% in 2016 to 4.5% in 2017 and 5.0% in 2018.24

Malawi is landlocked, and its agriculturally-centered and undiversified economy is import-dependent for many products, such as fuel and manufactured goods. These factors, along with poor physical and communications infrastructure (despite expanding cell phone access), contribute to high transport and import costs and inhibit economic growth and trade. Such structural challenges are the focus of state economic development and reform efforts. Key government policy objectives include private sector growth, trade liberalization and pricing control reductions, reduction of administrative overhead costs, civil service reforms, and the streamlining of investment licensing procedures. Several state firms have been or are being privatized. The government is also seeking to develop the mining sector. Malawi's first uranium mine, completed in 2009, has helped to diversify export earnings moderately.

Agriculture employs a large percentage of the labor force and is a key source of export earnings, but is subject to world market price shocks and weather-related risks, especially in the often arid far south. Most Malawians are smallholder farmers who produce food for direct subsistence needs and cash crops, notably tobacco, which is by far the top export. Many are also laborers on tea and sugar plantations. Malawi has a small manufacturing base focused on agricultural processing and limited consumer goods production, but Malawi's formal sector and skilled workforce are small.

Malawi reached the Highly Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) completion point in 2006 and subsequently qualified for debt relief under the IMF and World bank-administered Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (MDRI).25 Malawi is also a member of the Southern African Development Community (SADC), a regional intergovernmental body. SADC supports efforts to link Malawi's transport and electricity networks with those of other countries in southern Africa, and to advance the regionally integrated development of its members' mineral, agricultural, forestry, gas, and tourism sectors.

Cashgate, Donor Relations, and Related Prospects

Malawi's relations with donor governments could critically affect the long-term success of Mutharika's presidency. In 2014, Malawi was the fifth most aid-dependent country or territory globally; the amount of official development assistance (ODA) it received was equivalent to 75% of the value of government expenditures, and the percentage has been even higher in the past (reaching a peak of 113% in 2012).26 When a corruption affair known as "Cashgate" came to light in 2013, most members of the European and multilateral agency Common Approach to Budget Support (CABS) group of donors, which had previously provided joint direct budget support to Malawi, instituted a hold on such aid. That hold remains in place. Most members of CABS, along with the United States, currently provide project-based or otherwise targeted development aid, rather than direct budget support, notably for social services, humanitarian needs, and infrastructure and public institutional development.

|

Ongoing Cashgate Affair Cashgate-related prosecutions and trials have continued in 2017, along with related asset seizures, and the matter remains an active public policy challenge.27 Cashgate centered on the manipulation of a government payment and fiscal controls system called the Integrated Financial Management System. It was allegedly used to carry out illegitimate transactions and issue fraudulent check payments causing a reported $45 million, and possibly far more in losses. The amount may never be known, as many transactions were erased from the system. A leaked June 2016 confidential forensic audit performed by the UK firm RSM Risk Assurance Services determined that about 236 billion in Malawi Kwatcha (about $348 million) could not be reconciled and was possibly missing due to a range of corrupt practices and poor administration identified by the audit. The scheme was revealed during President Banda's tenure, and several officials from her administration and allies in other parties, were implicated—likely contributing to her election loss. Multiple individuals have been convicted and dozens more have been charged in relation to the scandal. Nonetheless, some analysts contend that political support for the anti-corruption campaign has waned as investigations into the extent of Malawi's graft have implicated members of both the ruling party and the opposition, spanning three administrations.28 Former President Banda, for her part, was named by some of those under prosecution as a beneficiary of the scheme, but she has not been charged. She has denied involvement, but reportedly has not returned to Malawi since departing in August 2014.29 |

Despite Cashgate investigations and prosecutions under the Banda and Mutharika governments and reported efforts by both administrations to prevent a recurrence of such an affair, donors remain concerned over government budget execution capacity and the potential for corruption. In January 2017, such concerns were substantiated with the emergence of allegations that the Malawian government had purchased maize from neighboring Zambia at an inflated price through opaque middlemen. Investigations into the alleged graft—dubbed "Maizegate"—resulted in the firing of the Minister of Agriculture, Irrigation, and Water Development.30

In late 2015, the IMF suspended a $145 million extended credit program due to Malawi's failure to meet jointly agreed economic program targets. In March 2016, however, noting "a concerted effort to put the program back on track," the IMF signaled its intent to reinstate the extended credit facility arrangement; in June, the program was extended until December 2016.31 It was subsequently re-extended through June 2017. The European Union is reportedly assessing the government's success in meeting policy targets as a condition for potentially resuming aid, and the World Bank resumed cooperation with Malawi in May 2017.32

Human Rights

Like many African countries, Malawi has a mixed human rights record. Key issues in Malawi include institutional weaknesses, a lack of education and training, and resource limitations, which have inhibited access to justice. There have also been reports of misconduct and/or the extralegal use of force or other coercive actions by security and law enforcement agencies. A number of institutions, however, are involved in efforts to foster human and legal rights advocacy, monitoring, and capacity-building efforts, including the government's Malawi Human Rights Commission and multiple nongovernmental organizations.

According to the State Department, the "most significant human rights problems" in Malawi in 2016 included

unlawful police killings; excessive use of force, including torture by security officers; and sexual exploitation of children, including early and forced marriage. Other human rights problems included arbitrary arrest and detention; harsh prison and detention center conditions; lengthy pretrial detention; mob violence; societal discrimination and violence against women; harmful traditional practices, including sexual initiation rituals; trafficking in persons; discrimination against lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex (LGBTI) persons; discrimination against persons with disabilities; violence against persons with albinism; and child labor.

A notable group of victims who face increasingly serious human rights threats are Malawi's estimated 7,000 to 10,000 persons with albinism. In a recent report, Amnesty International (AI) summarized the threat that albinos have increasingly faced in recent years. It reported that in Malawi in 2016

an unprecedented wave of violent attacks against people with albinism exposed a systemic failure of policing. Individuals and criminal gangs perpetrated abductions, killings and grave robberies as they sought body parts that they believed contain magical powers. Women and children were particularly vulnerable to killings, sometimes targeted by their own relatives.33

The government is attempting to address these and other human rights challenges, such as elder abuse. In his 2016 State of the Nation Address, President Mutharika reported that his government had investigated the root causes of attacks and killings of albinos, and prosecuted and convicted suspects accused of such acts. He also reported on a government public awareness campaign centered on promoting and protecting the human rights of the elderly and countering witchcraft-related violence.34 He announced plans to review the 1911 Witchcraft Act,35 undertake efforts focused on the rights and welfare of the disabled, and develop a National Elderly Bill. He also gave an update on Malawi's compliance with various international human rights treaty reporting requirements.

Homosexuals also face widespread social discrimination in Malawi. State bias against homosexuals was a point of U.S.-Malawian bilateral contention during the Wa Mutharika administration, but President Banda suspended anti-homosexuality laws in 2012 and committed to repealing them, though this did not occur.36 In late 2015, a neighborhood watch group detained two men whom they suspected of being homosexual and turned them over to police, and a criminal case against the men was initiated. The Mutharika administration later ended the prosecution and stated that no further arrests or prosecutions would occur pending the outcome of a parliamentary review of sexual conduct laws.37 The government has announced plans to hold public consultations on whether to reform laws banning homosexuality, but such efforts are controversial; in late 2016, there was a large protest by religious groups opposed to homosexuality. Also in late 2016, notwithstanding the reported suspension of anti-gay laws, a magistrate's court convicted two men of participating in homosexual sexual acts.38

U.S. Relations

U.S.-Malawi relations warmed following Malawi's democratic transition in 1994, but became strained during President Wa Mutharika's second term (see "Political Background," above), before improving under Banda. General acceptance by Malawians of the legitimacy of the 2014 electoral process, despite some reported flaws in its administration, was a key consideration for continued close bilateral cooperation.39 U.S. relations with Malawi under President Mutharika have thus far remained close and positive; he attended the Obama Administration's 2014 U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit and reportedly meets regularly with the U.S. ambassador.40 According to the State Department, the United States and Malawi have "worked together to advance health, education, agriculture, energy, and environmental stewardship in Malawi" and the two countries' "views on the necessity of economic and political stability in southern Africa generally coincide."41 Malawi is a participant in the Young African Leaders Initiative, a learning exchange program. Malawi is eligible for trade benefits, including apparel benefits, under the U.S. African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA, Title I, P.L. 106-200, as amended).

There are currently no indications of any changes to bilateral ties under the Administration of President Donald Trump, although the Trump Administration has proposed general cuts to aid for Malawi that could affect the extent and focus of bilateral cooperation and engagement.

U.S. Assistance

State Department and USAID bilateral assistance to Malawi totaled $222.4 million in FY2015, not including $21.3 million in additional emergency disaster aid (see Table 1). FY2016 bilateral aid is estimated at $260.9 million, supplemented with an additional $102.6 million in disaster response funding, primarily comprising food aid. The Obama Administration requested $195.6 million for FY2017. In the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2017 (P.L. 115-31) congressional appropriators mandated that a minimum of $56 million in Development Assistance account funds be allocated to Malawi, and that of these funds, up to $10 million be made available for higher education programs.

The Trump Administration requested $161.3 million for Malawi in FY2018, not including any Development Assistance (DA) account funding.42 This request would almost exclusively fund global health programs.43 An additional $317,000 would support International Military Education and Training (IMET) programs.

In recent years, Malawi has also received additional USAID regional program aid; some centrally allocated USAID and State Department functional program aid for which country allocations are not routinely reported; and periodic functionally specialized, generally small-scale program aid from other federal agencies. U.S. development programs in Malawi have centered on efforts to help the government counter the HIV/AIDS epidemic (9.1% of adults are HIV-positive); increase food security; spur agriculture-based economic growth; and reduce poverty. Additional aims of U.S. assistance have included strengthening public and private institutions to ensure effective social service delivery, with a focus on health and education; increasing private sector and civil society capacities; preserving biodiversity; and strengthening local capacities to mitigate climate change effects.44

A significant portion of U.S. assistance for Malawi has been allocated toward health programs, including through the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), the President's Malaria Initiative (PMI), and the presidential Global Health Initiative (GHI). Malawi has also been a Feed the Future (FTF) participant country. FTF efforts in Malawi have focused on expanding production of sweet potatoes, enhancing marketing and production value chains for legumes and horticultural production, and expanding access to seeds. Among other ends, these activities have been intended to expand access to nutrition and increase income opportunities for the country's predominantly poor farming sector.45 Development Assistance (DA) has focused on improving social development prospects, promoting sustainable livelihoods and incomes, and expanding participatory governance. Malawi's military receives IMET assistance and has participated in the State Department's African Contingency Operations Training Assistance (ACOTA) program, which focuses on peacekeeping training.46

MCC

Malawi was awarded a $21 million Millennium Challenge Corporation Threshold program in 2005 that focused on enhancing good governance and fighting corruption. The MCC approved a $350 million, 5-year MCC compact for Malawi in January 2011, but little progress was initially made due to concern over the Wa Mutharika administration's policies, and the compact was suspended in March 2012. The Compact was reinstated in June 2012, after the inauguration of President Banda.47 It entered into force in September 2013 and is slated to be completed in September 2018.48 The Compact focuses on improving the national power grid and hydropower generation efficiency; institutionally and financially rebuilding the national power utility and supporting regulatory reforms; and mitigating and managing environmental constraints on hydropower facilities. The goal is to reduce energy costs and enhance economic productivity.

Table 1. State Department and USAID-Administered Assistance for Malawi

State Department- and USAID-administered funds

Appropriations in millions of dollars

|

FY2014 (actual) |

FY2015 (actual) |

FY2016 (actual) |

FY2017 (request) |

FY2018 (request) |

|

|

DA |

51.5 |

45.0 |

46.3 |

30.0 |

- |

|

GHP–State |

64.2 |

77.6 |

71.1 |

88.0 |

120.0 |

|

GHP–USAID |

71.2 |

71.2 |

70.7 |

70.4 |

41.0 |

|

IMET |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

|

FFPa |

8.9 |

28.3 |

72.7 |

7.0 |

- |

|

TOTAL |

196.0 |

222.4 |

260.9 |

195.6 |

161.3 |

Sources: State Department, Congressional Budget Justifications for Foreign Operations (CBJ), FY2015-FY2018; USAID, Southern Africa-Drought Fact Sheet #4, Fiscal Year (FY) 2017, January 30, 2017; and Southern Africa–Disaster Response Fact Sheet #7, Fiscal Year (Fy) 2017, April 27, 2017.

Notes: DA = Development Assistance; GHP = Global Health Programs; IMET = International Military Education and Training; FFP = Food For Peace (P.L. 480 Title II). Figures do not include emergency humanitarian assistance or certain types of aid provided through regional programs. Totals may not add up due to rounding.

a. The Trump Administration did not request FFP aid in FY2018, and instead seeks to fund all emergency food aid under the International Disaster Assistance (IDA) account. FFP aid may be used for developmental purposes and for emergency food need. FFP levels reported in this table are those reported in annual CBJ. Some additional emergency food needs may be funded by additional FFP or IDA funding. IDA funds also may fund non-food humanitarian emergency needs. Total IDA account breakouts are not routinely reported by country, USAID's Office of Food for Peace, which administers both FFP and IDA food aid, merges FFP and IDA in their reporting on emergency food aid. Total USAID IDA and FFP emergency response funding for Malawi totaled $102.6 million in FY2016 and, as of April 27, 2017, $28.5 million in FY2017,

Outlook

Malawi is likely to remain among the world's most impoverished countries for years to come, but socioeconomic conditions may improve as a result of ongoing investment in public goods and services, efforts to alleviate poverty, and initiatives aimed at promoting private sector growth. U.S.-Malawian relations will likely continue to center on U.S. assistance and development cooperation. The nature and extent of such engagement may, nevertheless, depend on the outcome of emerging debate over U.S. assistance levels and foreign policy priorities under the Trump Administration. While there are some indications that Congress may not enact cuts as sharp as those proposed by the Administration, U.S. development cooperation will be strongly affected by whether—and to what extent—the Trump Administration continues key development initiatives pioneered by past Administrations, such as PEPFAR and FTF. These initiatives are key delivery channels for aid to Malawi, and any major reordering of the scale, scope, or goals of such efforts may significantly change the nature and focus of bilateral relations.