Introduction

The earned income tax credit (EITC), when first enacted in 1975, was a modest tax credit providing financial assistance to low-income working families with children. (It was also initially a temporary tax provision.) Today, the EITC is one of the federal government's largest antipoverty programs, having evolved through a series of legislative changes over the past 40 years. Since the EITC's enactment, Congress has shown increasing interest in using refundable tax credits for a variety of purposes, from reducing the tax burdens of families with children (the child tax credit), to helping families afford higher education (the American opportunity tax credit), to subsidizing health insurance premiums (the premium assistance tax credit). The legislative history of the EITC may provide context to current and future debates about refundable tax credits.

The report first provides a general overview of the current credit. The report then summarizes the key legislative changes to the credit and provides analysis of some of the congressional intentions behind these changes. An overview of the current structure of the EITC can be found in Appendix A at the end of this report. For more information about the EITC, see CRS Report R43805, The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC): An Overview.

An Overview of the History of the EITC

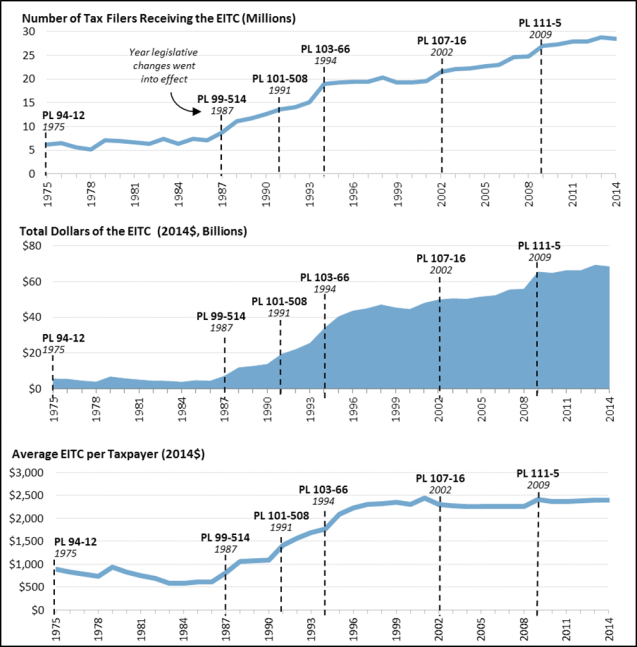

Major legislative changes to the EITC over the past 40 years can generally be categorized in one of two ways: Those that increased the amount of the credit by changing the credit formula or those that changed eligibility rules for the credit, either expanding eligibility to certain workers (for example, certain servicemembers) or denying the credit to others (for example, workers not authorized to work in the United States). Together, these changes reflect congressional intent to expand this benefit while also better targeting it to certain recipients. A summary of some of the major changes to the EITC can be found in Table 1. A summary of the growth in the EITC in terms of both the amount of the credit and the number of claimants over time can be found in Figure 1, which includes the dates of key legislative changes to the credit.

Before Enactment

The origins of the EITC can be found in the debate in the late 1960s and 1970s over how to reform welfare—known at the time as Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC).1 During this time, there was increasing concern over the growing numbers of individuals and families receiving welfare.2 In 1964, fewer than 1 million families received AFDC. By 1973, the AFDC rolls had increased to 3.1 million families. Some policymakers were interested in alternatives to cash welfare for the poor. Some welfare reform proposals relied on the "negative income tax" (NIT) concept. The NIT proposals would have provided a guaranteed income to families who had no earnings (the "income guarantee" that was part of these proposals). For families with earnings, the NIT would have been gradually reduced as earnings increased.3 Influenced by the idea of a NIT, President Nixon proposed in 1971 the "family assistance plan" (FAP)4 that "would have helped working-poor families with children by means of a federal minimum cash guarantee."5

Senator Russell Long, then chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, did not support FAP because it provided "its largest benefits to those without earnings"6 and would, in his opinion, discourage people from working. Instead, Senator Long proposed a "work bonus" plan that would supplement the wages of poor workers. Senator Long stated that his proposed "work bonus plan" was "a dignified way" to help poor Americans "whereby the more he [or she] works the more he [or she] gets."7 Senator Long also believed his "work bonus plan" would "prevent the social security tax from taking away from the poor and low-income earners the money they need for support of their families."8

1975-1986: An Earnings-Based Credit for Workers with Children

The "work bonus plan" proposal was passed by the Senate in 1972, 1973, and 1974, but the House did not pass it until 1975. The "work bonus plan" was renamed the earned income tax credit and was enacted on a temporary basis as part of the Tax Reduction Act of 1975 (P.L. 94-12). As originally enacted, the credit was equal to 10% of the first $4,000 in earnings. Hence, the maximum credit amount was $400. The credit phased out between incomes of $4,000 and $8,000. The credit was originally a temporary provision that was only in effect for one year, 1975.

In addition to encouraging work and reducing dependence on cash welfare, the credit was also viewed as a means to encourage economic growth in the face of the 1974 recession and rising food and energy prices. As the Finance Committee Report on the Tax Reduction Act of 1975 stated:9

This new refundable credit will provide relief to families who currently pay little or no income tax. These people have been hurt the most by rising food and energy costs. Also, in almost all cases, they are subject to the social security payroll tax on their earnings. Because it will increase their after-tax earnings, the new credit, in effect, provides an added bonus or incentive for low-income people to work, and therefore, should be of importance in inducing individuals with families receiving Federal assistance to support themselves. Moreover, the refundable credit is expected to be effective in stimulating the economy because the low-income people are expected to spend a large fraction of their disposable incomes.

|

P.L. 94-12 |

P.L. 95-600 |

P.L. 98-369 |

P.L. 99-514 |

P.L. 101-508 |

P.L. 103-66 |

P.L. 107-16 |

P.L. 111-5 |

|

|

Maximum statutory credit for eligible taxpayers including variation based on the number of qualifying childrena |

$400 Enacting legislation |

$500 |

$550 |

$800 |

one, $1,057 two or more, |

none, $323 one, $2,152 two or more, |

same |

0-2, same 3 or more, |

|

Credit Formula Based on: |

||||||||

|

Earnings |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

Number of Children |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||

|

Marital Status |

X |

X |

||||||

|

Credit Available to Childless Workers |

X |

X |

X |

|||||

|

Credit Adjusted Annually for Inflation |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

Source: CRS analysis of Internal Revenue Code (IRC) § 32, P.L. 94-12, P.L. 95-600, P.L. 98-369, P.L. 99-514, P.L. 101-508, P.L. 103-66, P.L. 107-16, P.L. 111-5.

a. Statutory amounts do not reflect annual adjustments for inflation.

The same report also emphasized that the EITC's prime objective should be "to assist in encouraging people to obtain employment, reducing the unemployment rate, and reducing the welfare rolls."10 One indication of the extent to which this credit was meant to replace cash welfare was that the bill had originally included a provision that would have required states to reduce cash welfare by an amount equal to the aggregate EITC benefits received by their residents. This provision was ultimately dropped in the conference committee.11 In addition, since the EITC was viewed in part as an alternative to cash welfare, it was generally targeted to the same recipients—single mothers with children.12 (Childless low-income adults would not receive the EITC until the 1990s, discussed subsequently.)

The credit was extended several times before being made permanent by the Revenue Act of 1978 (P.L. 95-600).13 This law also increased the maximum amount of the credit to $500.14 In summary materials of that bill, the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) stated that the credit was made permanent because "Congress believed that the earned income credit is an effective way to provide work incentives and relief from income and Social Security taxes to low-income families who might otherwise need large welfare payments."15 The modest increase in the amount of the credit in 1978 was seen as a way to take into account the increase in the cost of living since 1975 (the credit was not adjusted for inflation). Subsequent increases in the amount of the credit in 1984 (P.L. 98-369) and 1986 (P.L. 99-514) were also viewed as a way to adjust the credit for cost-of-living increases, as well as increases that had occurred to Social Security taxes.16 (The 1986 law also permanently adjusted the credit annually for inflation going forward.)

1990s: Expanding the Credit Amount While Limiting Eligibility

In the early 1990s, legislative changes again increased the amount of the EITC. Eligibility for the credit was also expanded to include childless workers. Several years later, in light of concerns related to the increasing cost of the EITC, as well as concerns surrounding noncompliance, additional changes were made to the credit with the intention of reducing fraudulent claims, better targeting benefits, and improving administration.

Adjusting the Credit for Family Size and Expanding Availability to Childless Workers

Over time, policymakers began to turn to the EITC as a tool to achieve another goal: poverty reduction. A 1989 Wall Street Journal article described the EITC as "emerging as the antipoverty tool of choice among poverty experts and politicians as ideologically far apart as Vice President Dan Quayle and Rep. Tom Downey, a liberal New York Democrat."17 Unlike other policies targeted to low-income workers, like the minimum wage, the EITC was viewed by some as better targeted to the working poor with children.18 In addition, unlike creating a new means-tested benefit program, the EITC was administered by the IRS. This may have appealed to some policymakers who did not wish to create additional bureaucracy when administering poverty programs.19

To use the credit as a poverty reduction tool, the formula used to calculate the credit was modified. As previously discussed, the EITC as originally designed did not vary by family size. Thus, as family size increased, the credit became less effective at helping families meet their needs. The EITC was restructured to vary based on family size beginning with the Omnibus Reconciliation Act of 1990 (OBRA90; P.L. 101-508) and greatly expanding with the Omnibus Reconciliation Act of 1993 (OBRA93, P.L. 103-66).20 Specifically, following these legislative changes, the EITC was calculated such that at any given level of earnings, the credit was one size for a taxpayer with one child and larger for taxpayers with two or more children.21

OBRA93 also—for the first time—extended the credit to childless workers. Unlike the expansion of the credit to workers with more than one child, the main rationale for this "childless EITC" was not poverty reduction.22 Instead the credit was intended to partly offset a gasoline tax increase included in OBRA93.23 The credit for childless workers was smaller than the credit for individuals with children—a maximum of $323 as opposed to $2,152 for those with one child and $3,556 for those with two or more children in 1996. The childless EITC was also only available to adults aged 25 to 64 who were not claimed as dependents on anyone's tax return. Notably, aside from inflation adjustments, the formulas for the childless EITC and the EITC for individuals with one or two children have remained unchanged since OBRA93.

Targeting the Credit

Other legislation passed later in the 1990s—The Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (PRWORA; P.L. 104-193) and the Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997 (P.L. 105-34)—included modifications to the EITC intended to reduce fraud, limit eligibility to individuals authorized to work in the United States, prevent certain higher-income taxpayers from claiming the credit, and improve administration of the credit.

Before and during consideration of PRWORA, Congress was increasingly concerned with the rising cost of the credit. Some policymakers attributed the increasing cost of the program to the significant legislative expansions that had occurred earlier in the decade and the expansion of EITC eligibility to childless workers.24 In addition, there were concerns, as Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich stated, that "as the EITC becomes more generous, it invite[s] fraud and abuse."25 A 1994 GAO report had identified significant amounts of the credit claimed in error.26 Other policymakers were concerned that the credit was available to certain higher-income taxpayers—specifically those with little earned income, but significant unearned income (like interest income, dividends, and rent and royalty income).27 Finally, "Congress did not believe that individuals who are not authorized to work in the United States should be able to claim the credit."28

Ultimately, PRWORA addressed these concerns by "tighten[ing] compliance tax rules and mak[ing] it harder for some people to qualify for the credit."29 These changes included expanding the definition of "investment income" above which an individual would be ineligible for the credit,30 expanding the definition of income used to phase out the credit so certain taxpayers with capital losses would be ineligible for the credit,31 and denying the EITC to individuals who did not provide an SSN for work purposes.32

One year after PRWORA, Congress modified the EITC again with the intention of both improving administration and further limiting the ability of certain higher-income taxpayers to claim the credit. The Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997 (TRA97; P.L. 105-34) created penalties for taxpayers who claimed the credit incorrectly, including denying the credit to individuals for 10 years if they claimed the credit fraudulently, that were intended to improve administration of the credit.33 And if after this period of time, the taxpayer ultimately was eligible for the credit and wished to claim it, they would need to provide the IRS with additional information (as established by the Treasury) to prove eligibility. According to the JCT, these new penalties were enacted because "Congress believed that taxpayers who fraudulently claim the EITC or recklessly or intentionally disregard EITC rules or regulations should be penalized for doing so."34 In addition, TRA97 included new requirements of paid tax preparers that were also meant to improve administration and reduce errors.

Finally, TRA97 expanded the definition of income used in phasing out the credit, by including additional categories of passive (i.e., unearned) income. The rationale for this change, according to the JCT, was that "Congress believed that the definition of AGI used currently [prior to TRA97] in phasing out the credit [was] too narrow and disregard[ed] other components of ability-to-pay."35

2000s: Adjusting the Credit for Marital Status and Family Size

In the 2000s, additional changes to the EITC credit formula were enacted by Congress. These legislative changes expanded the credit for certain recipients—namely married couples and larger families.

Reducing the "Marriage Penalty"

At beginning of 2000, there was bipartisan congressional interest in reducing tax burdens of married couples generally (although the means by which they intended to achieve this goal varied).36 For low-income taxpayers with little or no tax liability, a marriage penalty is said to occur when the refund the married couple receives is smaller than the combined refund of each partner filing as unmarried. (Marriage bonuses also arise in the U.S. federal income tax code.)37 In 2001, the JCT identified the structure of the EITC as one of the primary causes of the marriage penalty among low-income taxpayers.38 Specifically, the JCT found that the phaseout range of the credit and its variation based on number of children could result in smaller credits among married EITC recipients than the combined credits of two singles. As the JCT stated in 2001,39

Because the [earned income credit] EIC increases over one range of income and then is phased out over another range of income, the aggregation of incomes that occurs when two individuals marry may reduce the amount of EIC for which they are eligible. This problem is particularly acute because the EIC does not feature a higher phase out range for married taxpayers than for heads of households. Marriage may reduce the size of a couple's EIC not only because their incomes are aggregated, but also because the number of qualifying children is aggregated. Because the amount of EIC does not increase when a taxpayer has more than two qualifying children, marriages that result in families of more than two qualifying children will provide a smaller EIC per child than when their parents were unmarried. Even when each unmarried individual brings just one qualifying child into the marriage there is a reduction in the amount of EIC per child, because the maximum credit for two children is generally less than twice the maximum credit for one child.

EGTRRA reduced the EITC marriage penalty by increasing the income level at which the credit phased out for married couples. This "marriage penalty relief" was scheduled to gradually increase to $3,000 by 2008. In 2009, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA; P.L. 111-5) temporarily increased EITC marriage penalty relief to $5,000.

Expanding the EITC for Families with Three or More Children

In addition to expanding marriage penalty relief, ARRA also temporarily created a larger credit for families with three or more children by increasing the credit rate for these families from 40% to 45%. A larger credit rate of 45% (as opposed to 40%), while leaving other EITC parameters unchanged (earned income amount and phaseout threshold), resulted in a larger credit for families with three or more children.

These two ARRA modifications to the EITC were originally enacted as part of legislation meant to provide temporary economic stimulus. There was debate surrounding whether these temporary modifications should be further extended. After these changes were enacted in 2009, the Obama Administration proposed making these provisions permanent as part of its budget proposals.40,41 During negotiation on the "fiscal cliff" legislation at the end of 2012 (The American Taxpayer Relief Act [ATRA; P.L. 112-240]), some Senators expressed a desire to have the EITC modification made permanent.42 ATRA extended these modifications for five years, through the end of 2017. Ultimately, increased marriage penalty relief and the larger credit for families with three or more children were made permanent by the Protecting Americans from Tax Hikes Act (PATH Act; Division Q of P.L. 114-113).43

Appendix A. Current Structure of the EITC

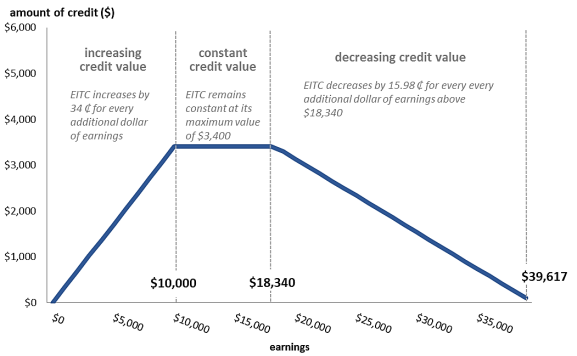

There are eight formulas currently in effect to calculate the EITC (four for unmarried individuals and four for married couples, depending on the number of children they have), illustrated in Table A-1.44

|

Number of Qualifying Children |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 or more |

|

unmarried tax filers (single and head of household filers) |

||||

|

credit rate |

7.65% |

34% |

40% |

45% |

|

earned income amount |

$6,670 |

$10,000 |

$14,040 |

$14,040 |

|

maximum credit amount |

$510 |

$3,400 |

$5,616 |

$6,318 |

|

phaseout amount threshold |

$8,340 |

$18,340 |

$18,340 |

$18,340 |

|

phaseout rate |

7.65% |

15.98% |

21.06% |

21.06% |

|

income where credit = 0 |

$15,010 |

$39,617 |

$45,007 |

$48,340 |

|

married tax filers (married filing jointly) |

||||

|

credit rate |

7.65% |

34% |

40% |

45% |

|

earned income amount |

$6,670 |

$10,000 |

$14,040 |

$14,040 |

|

maximum credit amount |

$510 |

$3,400 |

$5,616 |

$6,318 |

|

phaseout amount threshold |

$13,930 |

$23,930 |

$23,930 |

$23,930 |

|

phaseout rate |

7.65% |

15.98% |

21.06% |

21.06% |

|

income where credit = 0 |

$20,600 |

$45,207 |

$50,597 |

$53,930 |

Source: IRS Revenue Procedure 2016-55 and Internal Revenue Code (IRC) Section 32.

For any of the eight formulas, the credit has three value ranges similar to those illustrated in Figure A-1, for an unmarried taxpayer with one child. First, the credit increases to its maximum value from the first dollar of earnings until earnings reach the "earned income amount." Over this "phase-in range" the credit value is equal to the credit rate multiplied by earnings. When earnings are between the "earned income amount" and the "phaseout threshold"—referred to as the "plateau"—the credit amount remains constant at its maximum level. For each dollar over the "phaseout threshold," the credit is reduced by the phaseout rate until the credit equals zero. This final range of income over which the credit falls in value is referred to as the "phaseout range."