Introduction and Background

The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) provides supplemental nutrition-rich foods and nutrition education (including breastfeeding promotion and support), as well as referrals to health care and social services, to low-income, nutritionally at-risk women, infants, and children up to five years old. Eligible women are specifically limited to those pregnant and postpartum (if breastfeeding, women are eligible for more benefits for a longer period of time). The WIC program seeks to improve the health status of its participants and prevent the occurrence of health problems during critical times of growth and development.1

WIC is a federally funded program administered by the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Food and Nutrition Service (USDA-FNS). In FY2016, approximately 7.7 million people participated in WIC each month in programs run by 90 state agencies (50 states, District of Columbia, 5 U.S. territories, and 34 Indian Tribal Organizations).2 USDA has said roughly half of all infants in the United States participate in the WIC program.3

This report provides an overview of the WIC program, including administration, funding, eligibility, benefits, benefits redemption, and cost containment policies. While this report is meant to be a primer and is not focused on tracking major policy issues, it may be useful for the reader to note that this report does discuss features of the WIC program that are often the topic of policy debate: funding, eligible foods, and the redemption of benefits.

Authorization and Reauthorization

The WIC program dates back to a 1972 amendment to the Child Nutrition Act, which created WIC as a two-year pilot program. WIC became a permanent program in 1975 and remains authorized by Section 17 of the Child Nutrition Act (codified at 42 U.S.C. 1786). Congressional jurisdiction over this law has typically been exercised by the Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry and the House Committee on Education and the Workforce.

Congress periodically reviews and reauthorizes expiring authorities under the Child Nutrition Act, generally in conjunction with the "Child Nutrition Programs,"4 which are authorized by the Richard B. Russell National School Lunch Act, Section 32 of the Act of August 24, 1935, and the Child Nutrition Act.5 WIC and the Child Nutrition Programs were most recently reauthorized in 2010 through the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010 (HHFKA, P.L. 111-296), and those authorities that expire do so after September 30, 2015 (the end of FY2015). During the 114th Congress, committees of jurisdiction marked up bills to reauthorize WIC but reauthorization was not completed. As of the date of this report, no bills to reauthorize WIC have been introduced or marked up in the 115th Congress.

The WIC Farmers' Market Nutrition Program (WIC FMNP) is closely related to WIC and also authorized within Section 17 of the Child Nutrition Act (Section 17(m)). This program, which serves much of WIC's population, is also typically reauthorized during the reauthorization of WIC and the Child Nutrition Program. This report discusses WIC and not WIC FMNP; however, a brief overview of that program is provided in Appendix C.

For information on WIC reauthorization laws, see the following:

- CRS In Focus IF10266, An Introduction to Child Nutrition Reauthorization

- CRS Report R44373, Tracking the Next Child Nutrition Reauthorization: An Overview

- CRS Report R41354, Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization: P.L. 111-296.

Federal, State, and Local Administration

WIC operates through a federal, state, and local partnership. The U.S. Department of Agriculture's Food and Nutrition Service (USDA-FNS) administers the WIC program at the federal level. USDA-FNS provides cash grants for foods and "Nutrition Services and Administration" to 90 state agencies (50 states, District of Columbia, 5 U.S. territories, and 34 Indian Tribal Organizations), which operate the program through local WIC agencies and clinics.6

At the federal level, USDA-FNS is responsible for issuing and enforcing regulations, providing technical assistance to state agencies, and conducting studies and producing reports to evaluate the WIC program.7 At the state level, state agencies are generally responsible for program operations within their jurisdictions. States provide subgrants and technical assistance to local WIC agencies. Federal law and regulations allow states some flexibility in program operations, including options for food delivery systems and benefit redemption systems.8 States also have discretion in deciding the specific brands, types, and package sizes to include in their approved WIC food packages, within the bounds of federal regulations.9 At the local level, local WIC agencies—generally state and county health departments—provide WIC services and benefits directly or through local service sites and clinics. As of February 2015, there are approximately 1,900 local WIC agencies operating the program in approximately 10,000 local service sites or clinics.10

Funding

Funding for WIC food and services is primarily provided by the federal government; though some states supplement their programs with their own funding, WIC law does not require matching funds. WIC's funding is categorized as discretionary with funding amounts determined entirely through the annual appropriations process.11 Since the late 1990s, the appropriations committees' practice has been to provide enough funds for WIC to serve all eligible applicants who seek program benefits (i.e., all forecasted participants).12 Lower levels of funding for the WIC program could reduce the number of pregnant and postpartum women, infants, and children served.

The WIC program is typically funded through the annual Agriculture and Related Agencies appropriations bill. Funds are available for two years (e.g., FY2015 appropriations are available for obligation through FY2016). Table 1 displays the funding provided for the WIC account in recent years' appropriations laws.

|

FY2012 |

FY2013 |

FY2014 |

FY2015 |

FY2016 |

|

|

WIC Account Total |

$6,618.5 |

$6,522.2 |

$6,715.8 |

$6,623.0 |

$6,350.0b |

Source: CRS, compiled from respective appropriations laws and related congressional documents.

a. This funding level displayed is post-sequester. For more information on the FY2013 sequester of funds provided by the Agriculture and Related Agencies appropriations bill, based on the Budget Control Act of 2011, see CRS Report R43110, Agriculture and Related Agencies: FY2014 and FY2013 (Post-Sequestration) Appropriations.

b. In addition, Section 751 provided $220 million for management information systems and WIC EBT by rescinding FY2015 carryover and recovery funding.

The majority of WIC's funding is distributed by USDA-FNS to states based upon allocation formulas described in federal regulations.13 The formulas used to allocate federal funds—both money from the annual appropriation and any unused money recovered and reallocated—are designed to (1) guarantee states enough money to maintain their previous year's operating level and caseload (with adjustments for inflation), and (2) distribute any extra dollars to grantees receiving comparatively less than their "fair share" of funds (based on their income-eligible WIC population and amount estimated as needed to serve their projected participation level).14 As needed and authorized, USDA-FNS may reallocate funding throughout the year.15 State-by-state allocation amounts for recent and past years can be found at USDA-FNS's website.16

In addition to the appropriated funding provided for the current fiscal year, WIC may carry over funds remaining from the prior year's appropriation; and in the event that these funds from two years prove insufficient, the program maintains a contingency fund that can be spent in any year.17 Table 2 displays three years of federal WIC obligations. Due to the availability of WIC's appropriated funds, obligated funds may include not only the current year's appropriation but carryover and contingency spending as well.

|

Project/Purpose |

FY2012 |

FY2013 |

FY2014 |

FY2015 |

|

Grants to States: |

||||

|

Supplemental Food |

4,780 |

4,823 |

4,889 |

4,680 |

|

Nutrition Services and Administration |

1,926 |

2,013 |

2,013 |

1,990 |

|

Subtotal, Grants to States |

6,706 |

6,835 |

6,902 |

6,670 |

|

Infrastructure Grants |

3 |

13 |

7 |

10 |

|

Technical Assistance |

- |

- |

0a |

0a |

|

Breastfeeding Peer Counselors |

60 |

55 |

60 |

60 |

|

Management Information Systems |

10 |

32 |

36 |

10 |

|

Program Evaluation & Monitoring |

10 |

5 |

8 |

13 |

|

Federal Administration |

9 |

10 |

6 |

3 |

|

WIC Contingency Funds |

368 |

- |

125 |

0 |

|

UPC Databaseb |

2 |

1 |

1 |

0a |

|

TOTAL WIC FUNDS OBLIGATED |

$7,168 |

$6,952 |

$7,145 |

$6,768 |

Sources: FY2012 data from FNS FY2015 Congressional Budget Justification (p. 32-63); FY2013, FY2014 data from FNS FY2016 Congressional Budget Justification (p. 32-67); FY2015 data from FNS FY2017 Congressional Budget Justification (p. 32-76).

Notes: Numbers may not add, due to rounding.

b. Per Section 17(h)(13) of the Child Nutrition Act of 1966 (42 U.S.C. 1786(h)(13)), funding for this purpose is directly appropriated. This Universal Product Code (UPC) database supports states' transition to EBT.

As Table 2 shows, the bulk of WIC funding is provided as two types of grants for states: food grants, and Nutrition Services and Administration (NSA) grants. Food grant funds may be used to pay retail grocery stores for foods purchased by program participants; to acquire, store, and provide supplemental foods to participants; and to purchase or rent breast pumps.18 NSA grant funds may be used for participant certification costs, nutrition education activities, breastfeeding promotion and support activities, and salaries and administrative costs to provide these services.19 In general, money for food costs and NSA expenses must be kept separate; however, grantees may, under federal guidelines, convert food funding to support NSA costs. The WIC appropriation also includes federal funds for specified WIC purposes (e.g., Management Information Systems, Breastfeeding Peer Counselors) that may only be used to carry out approved projects or certain activities.

Because WIC's funding is tied to the cost of food items, the program has come to include a number of cost containment measures. Such measures include approved food lists with reasonably priced food items, rebates on infant formula and other authorized foods, and the selection of WIC vendors based on competitive prices. These policies are discussed in later sections of this report.

Eligibility

Mothers and children seeking WIC assistance must apply to their local WIC agencies and be screened for eligibility.20 WIC has a number of federal and state eligibility requirements including categorical, financial, and nutritional risk tests.21

Categorical Eligibility

To qualify for benefits, an individual must be categorically eligible (i.e., in a specified participant category).22 WIC serves individuals in the following participant categories:

- women during pregnancy and up to six weeks after delivery,

- breastfeeding women up to one year after delivery,

- non-breastfeeding women up to six months postpartum,

- infants, and

- children up to age five (eligibility ends at fifth birthday).

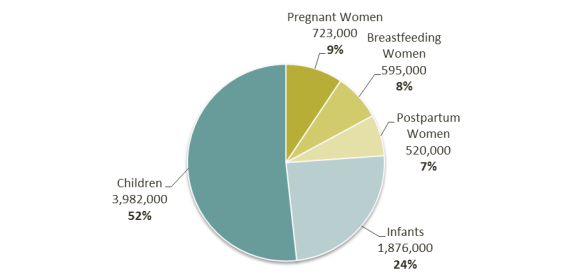

In FY2016, approximately 24% of participants were women, 24% were infants, and 52% were children under the age of 5.23 Participant characteristics by category are shown in Figure 1.

|

Figure 1. WIC Participant Characteristics, by Category FY2016, as of February 2017 |

|

|

Source: Figure prepared by CRS using USDA-FNS Administrative Data. Rounded to the nearest thousand and nearest 1%. |

Income Eligibility

Applicants must meet specific income guidelines to qualify for WIC, and applicants who participate in certain programs are deemed income-eligible. Federal law states that the maximum allowable gross family income of an applicant must not exceed the guidelines for reduced-price school meals, which are set at 185% of the federal poverty level (income eligibility guidelines shown in Table 3).24 Although federal regulation allows states to set income limits between 100% and 185% of the federal poverty level, currently all WIC state agencies set the income limit at the maximum of 185%. Federal law also sets the rules for what state agencies may exclude from counted income, with additional options provided in regulations.25

Applicants can become income-eligible for WIC by one of two pathways: (1) providing documentation of income below the 185% FPL threshold, or (2) being deemed eligible based on participation in certain means-tested programs (adjunctive eligibility).

In the first pathway, the income of the "family," not only the program participants, is considered. Federal regulation defines family largely as individuals (related or unrelated) who are living together.26 State agencies have the option to choose the income time frame for applicants (e.g., annually or a shorter term).27 WIC authorizing law includes state options for whether to count or exclude certain types of military income,28 and the regulations give additional flexibilities on income exclusions.29

Table 3. WIC Income Eligibility Guidelines, 185% of Federal Poverty Level

Effective from July 1, 2016, to June 30, 2017

|

Family/Household Size |

48 States, District of Columbia, Territories |

Alaska |

Hawaii |

|

1 |

$21,978 |

$27,454 |

$25,290 |

|

2 |

$29,637 |

$37,037 |

$34,096 |

|

3 |

$37,296 |

$46,620 |

$42,902 |

|

4 |

$44,955 |

$56,203 |

$51,708 |

|

5 |

$52,614 |

$65,786 |

$60,514 |

|

6 |

$60,273 |

$75,369 |

$69,320 |

|

7 |

$67,951 |

$84,952 |

$78,126 |

|

8 |

$75,647 |

$94,572 |

$86,969 |

|

Each additional family member |

+$7,696 |

+$9,620 |

+$8,843 |

Source: USDA-FNS website, http://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/wic-income-eligibility-guidelines (also published in the Federal Register).

Note: Annual thresholds are provided here, but the state agency may determine income based on a shorter time frame.

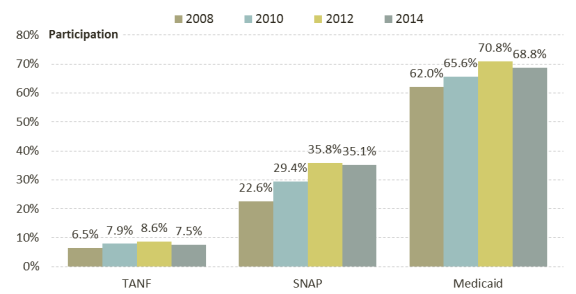

The second pathway, adjunctive eligibility, deems an applicant income-eligible based on their participation in certain means-tested programs. Applicants that currently receive or are eligible to receive Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Medicaid, or Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) are adjunctively eligible.30 Recent years' data—from a biennial USDA-FNS study using states' participant data—show that Medicaid has been consistently the most frequent source of adjunctive eligibility for WIC participants. Figure 2 displays the percentage of participants reporting participation in TANF, SNAP, and Medicaid. In April 2014, taking into account multiple program participation, 72.8% of WIC participants' income eligibility was determined through adjunctive eligibility.31 See Appendix Table A-2 for more detail on WIC participants' cross-program enrollment.

Because some states have income eligibility thresholds for SNAP and Medicaid that are above 185% of the federal poverty level, it is possible for WIC participants to have incomes over 185% of the federal poverty level. According to 2014 report data, 1.6% of WIC participants reported income above 185%.32 The vast majority of participants reporting income (74.1%) are at or below the federal poverty level.33

Nutritional Risk

Applicants must be at nutritional risk to qualify for WIC benefits, a rule that is unique to the WIC program, compared to other food assistance programs. Federal law recognizes five major types of nutritional risk,34 falling into two broad categories: "medically based risks" and "diet-based risks."35 Medically based risks include health conditions such as anemia, underweight, maternal age, history of pregnancy complications, or poor pregnancy outcomes. Diet-based risks refer to conditions that predispose applicants to inadequate nutritional patterns such as homelessness and migrancy.

To determine nutritional risk, a "competent professional authority," such as a physician, nutritionist, or nurse, must conduct a medical and/or nutritional assessment that includes the collection of anthropometric and biochemical measures, medical history, and dietary information from applicants and participants.36 This assessment allows WIC providers to tailor participant benefits and services.37

Residential Eligibility and Immigration Status

Applicants must reside within the state in which their eligibility is determined and cannot participate in WIC at more than one WIC clinic at the same time. WIC state agencies have the option to limit WIC participation to U.S. citizens, nationals, and qualified aliens.38

Other Eligibility Issues

Certification Period

Once certified eligible for WIC, participants are eligible for a certain period of time. At the end of a certification period, eligible participants must be recertified to continue receiving benefits. At recertification, the WIC clinic will confirm that the participant is still eligible for benefits (including nutritional risk) and may adjust benefits if categorical status and/or nutritional needs change. The lengths of WIC certification periods vary by participant category, but in general, participants are eligible to receive benefits for a six-month period. Pregnant women are certified for the duration of their pregnancy and up to six weeks postpartum. Breastfeeding women are certified for six-month periods up to one year after delivery, while non-breastfeeding women are certified only up to six months after delivery. States have options to certify infants through their first birthday and/or children for up to one-year periods.39

Priority System and Waiting Lists

Federal regulations require states to use a priority system to manage WIC applicant waiting lists, in the event that limited funding prevents all eligible applicants from being served. Because WIC funding is discretionary, the number of participants served by the program is limited by the level of funding appropriated by Congress (and the allocation of these funds by USDA-FNS to each state). However, since the late 1990s funding provided has been adequate to serve all eligible applicants.40 As a result, the priority system has largely gone unused in recent years—though the issue of WIC waiting lists is often brought up by program advocates in budget-related debates.41

In the event that limited funding prevents all eligible applicants from participating in the program, local agencies are to create and maintain a waiting list of applicants seeking benefits.42 Using a seven-point priority system, applicants are prioritized on the waiting list to ensure that those with the greatest nutritional risk and overall need can receive benefits.43 Typically, applicants with medically based nutritional risks (e.g., anemia) are prioritized over those with only diet-based nutritional risks (e.g., conditions that may lead to inadequate diet). Additionally, certain participant categories—infants, pregnant women, and breastfeeding women—are given higher priority levels than other categories such as children and non-breastfeeding women.

Benefits and Services Provided

The WIC program provides grants to states to provide benefits redeemable for specified supplemental foods (i.e., the WIC food package) and specified services. In addition to foods, WIC participants receive nutrition education, breastfeeding promotion and support, and referrals to healthcare and social services. Recent WIC grants to states for food costs as well as Nutrition Services and Administration (NSA) are displayed in Table 2, with historical funding in Table A-1.

Supplemental Food Package

Typically, WIC participants receive vouchers/checks or an electronic benefit transfer (EBT) card, which are then redeemed for specific supplemental foods, and in some respects tailored to the specific participant's needs. The federal food package regulations and the basis for states' approved food lists are discussed in this section. More information about the delivery of benefits and states' food lists is provided in a subsequent section, "Redemption of Food Benefits and Related Cost Containment Policies."

Federal Requirements for WIC-Eligible Foods

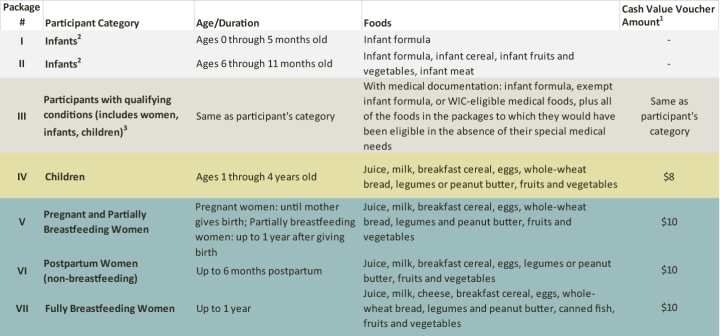

The supplemental food package in a given state is the result of federal regulation and state policies.44 Federal regulations list seven food packages, including eligible foods and their quantities, based on participant characteristics such as pregnancy status, breastfeeding practices, the age of children or infants, and dietary needs. Food items within the seven food packages include milk, juice, cereal, eggs, whole-wheat bread, legumes and peanut butter, cheese, canned fish, infant formula, infant cereal, and infant fruits, vegetables, and meats.45 State agencies create their eligible food lists within this framework.46 For instance, two states may make different brands of infant cereals WIC-eligible but both states' choices will meet the federal regulatory cereal requirements for sugar and fiber.47 States' WIC food selections are a prime way that states can control costs and make their WIC grants go further. The bulk of participants' benefits are for specific foods, but certain participants also receive a cash value voucher (CVV) for a specified monthly dollar amount to be redeemed for fruits and vegetables.48 Figure 3 summarizes the federal WIC food packages—noting which packages include a CVV.

WIC law, as amended in 2004 and 2010, requires USDA to conduct periodic ("not less than every 10 years") scientific reviews of foods included in the WIC food packages and to change the regulations as necessary.49 The current federal food package regulations, discussed in this section and displayed in Figure 3, are largely the result of significant revisions that began in 2003 with meetings of the National Academy of Sciences' Institute of Medicine (IOM) and continued with a 2007 interim rule that was finalized in 2014, with an added change (allowing CVV purchases of white potatoes) from Congress through the FY2015 appropriations law. The 2003 revision had been the first major revision since the 1970s. Note: In 2016, the IOM was renamed the Health and Medicine Division (HMD) of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM).50

Since the 2014 final rule, USDA-FNS engaged IOM/HMD for further review and assessment of the WIC food package studies. HMD convened an expert committee, and has since produced three reports, the third and final of which is expected to form the basis for FNS's next revision of the WIC food packages.51

Appendix B provides further detail on the WIC food package updates and proposed food package updates discussed in this section.

Issuance of Food Benefits

At a WIC clinic (local agency), a "competent professional authority" will assign an applicant to one of seven food packages (Figure 3). Participants are eligible to receive up to the maximum food benefits as determined by medical and nutritional need, not household income. Prescribed foods are typically reassessed at each recertification or when a participant's status changes (e.g., after a pregnant participant gives birth). Food package benefits are usually issued monthly.52

Currently, all but two state agencies have participants redeem their benefits at authorized WIC vendors (retailers).53 Most are issuing benefits through paper checks/vouchers, but (as of March 2017) 24 state agencies have implemented an electronic benefit transfer (EBT) system statewide.54 These benefit redemption concepts are discussed further in "Retail Food Delivery Systems and the Transition to EBT."

Nutrition Education, Breastfeeding, and Referral Services

In addition to food benefits, WIC also provides nutrition education and related support. States are required to ensure that nutrition education, including breastfeeding promotion and drug abuse education, is available to all pregnant, postpartum, and breastfeeding participants in the program.55 States develop and coordinate nutrition education services and oversee and support the administration of these benefits at local agencies. Under federal guidelines, WIC nutrition education must emphasize the relationship between nutrition, physical activity, and health and it must assist each participant in improving health status and achieving a positive change in dietary and physical activity habits.56 Nutrition education is provided through a number of approaches, including individual consultations, group counseling sessions, and online educational modules.

Though WIC does provide infant formula for infants whose mothers do not breastfeed, or do not exclusively breastfeed, WIC also promotes and supports breastfeeding in a variety of ways. States must establish standards and practices for breastfeeding promotion within nutrition education services.57 Additionally, states must spend an annual average of at least $21 per pregnant and breastfeeding woman to promote breastfeeding.58 Examples of breastfeeding promotion and support services include breastfeeding peer counselors, lactation consultants, classes and support groups, educational materials, and a breastfeeding hotline for questions.59 According to USDA-FNS, breastfeeding initiation has increased in recent years. 69.8% of WIC infants 6 to 13 months old were breastfed at some point in 2014, an increase from 67.1% in 2012.60

In an effort to integrate available services, state and local WIC agencies often provide applicants and participants with information on other health-related and public assistance programs (such as Medicaid, SNAP, and immunizations).61 WIC law requires that states provide Medicaid information to individuals that are income-eligible and not participating.62

Redemption of Food Benefits and Related Cost Containment Policies

State agencies, under federal guidelines, design and oversee the delivery of food benefits to participants. As stated earlier, almost all state agencies currently provide benefits using a voucher or EBT card for redemption at an authorized vendor. This section provides an overview of benefit redemption, states' transitions to EBT, authorization and management of vendors, and related cost containment policies.

Retail Food Delivery Systems and the Transition to EBT

Currently, most states have their participants redeem WIC benefits using a paper food instrument in the form of a check or voucher that specifies the types and quantities of foods that can be purchased at an authorized WIC vendor. Vendors send vouchers to the states, and the states reimburse vendors (using food grant funds) for WIC benefit redemptions. With paper vouchers, each will typically be redeemable for a group of approved foods (e.g., milk and eggs for the month), and WIC participants will have to redeem the entire group in the same transaction or lose the benefits if they make a partial transaction (e.g., only milk with the "milk and eggs" voucher).

WIC's 2010 reauthorization included the requirement that state agencies transition to using electronic benefit transfer (EBT) by October 1, 2020 (the end of FY2020).63 SNAP underwent the transition from paper food stamps to EBT from 1988 to 2004.64 WIC EBT (referred to by some states and stakeholders as "eWIC") replaces vouchers with a card, similar to a debit card, which keeps track of remaining and redeemed benefits. Policy rationales for this transition include program integrity considerations as well as improved services for participants and vendors.65 EBT, for instance, allows food benefits to be redeemed for each item individually or in groupings of the participant's choice. The WIC technology is more complex than SNAP's, however, and state agencies are at varying stages of making the transition.66 24 state agencies (20 states and 4 Indian Tribal Organizations), as of March 2017, have fully transitioned to WIC EBT.67 The fruit and vegetable cash-value voucher (CVV) is included in a transition to EBT, and so some states and stakeholders have begun referring to it instead as a cash-value benefit (CVB).

States' Cost Containment through Approved Foods

Approved Food Lists

Referred to earlier, the specific types and quantities of approved foods for redemption are a prime way states control food costs. In practice, states often control food costs by limiting participants' food-item selection to specific brands, economically priced package sizes and product forms, or least-cost brands. States' approved food lists, along with geographic variation in food costs, explain much of the variation between average food package costs in states. In FY2015, the average monthly food package cost was over $43 nationwide; individual state agencies' average monthly food package costs ranged from around $29 to $96.68 However, states balance cost containment considerations with participant satisfaction, as an approved food list that is too limited may stifle participation.69

Infant Formula (and Other Food) Rebates

Manufacturers' rebates for infant formula (and some other foods) also serve to contain WIC food costs.

Over time, one of the ways that WIC has controlled costs has been to require competitive bidding for infant formula, which has resulted in infant formula being available to states at well below market costs, especially due to manufacturers' discounts in the form of rebates to states. Infant formula has been shown to be the most expensive WIC food category. A study of FY2010 found that, without infant formula rebates, infant formula would have accounted for 42% of WIC food costs in FY2010; after rebates, formula costs were only 20%.70

Infant formula manufacturers submit bids through a state's (and, in some cases, alliances of states) competitive bidding process, and the contract is awarded to the manufacturer with the lowest price. The requirement that states pursue such cost containment systems for infant formula was added by the Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization Act of 1989 (P.L. 101-147), although some states had begun to enter into these arrangements prior to the law's passage and implementation.71

A rebate contract is a legal agreement between an infant formula manufacturer and a state (or multistate alliance).72 In a rebate contract, the state agency receives a rebate payment from the manufacturer, with total rebate payments depending upon how much infant formula was ultimately purchased with WIC benefits.73 The manufacturer receives the exclusive right to sell formula to the state's WIC participants.74 (Note: Some states competitively bid their milk- and soy-based formulas separately, so WIC participants buy formula from two manufacturers rather than a sole source.) WIC-authorized retailers are reimbursed for the "full" retail price of the infant formula, but state agencies then submit their reimbursements to the manufacturers for rebates.

Though the rebate may impact the manufacturers' profit on the WIC purchases, economic research indicates that the manufacturer who wins the state's WIC business also gains non-WIC business in the state.75

Infant formula rebates have significantly defrayed the costs of operating the WIC program. USDA-ERS estimates that, in FY2013, rebates generated $1.9 billion in savings.76 USDA-ERS also found that infant formula manufacturers in FY2013 were providing percentage discounts ranging from 77% to 98%, with 21 state agencies receiving discounts of 95% or greater.77

Although the law does not require states to pursue competitive bidding for other foods, some states have pursued rebate contracts for infant foods. According to March 2017 USDA-FNS data, eight WIC state agencies had rebate contracts for infant foods.78

Vendor Authorization and Management79

WIC uses the term "vendors" to describe the retailers that states authorize to accept WIC benefits.80 In FY2013, there were over 48,000 WIC authorized vendors nationwide.81 The sections that follow provide an overview of how states authorize WIC vendors and federal and state price-related policy impacting cost containment in WIC.

States' Authorization of Vendors

Vendors include a variety of retailers from supermarkets to convenience stores to military commissaries. State agencies are responsible for setting criteria and authorizing WIC vendors, within the framework of federal law and regulations. State agencies select and authorize vendors based on a set of criteria, such as competitive pricing, minimum stocking requirements of supplemental foods, and business integrity.82 If a vendor satisfies the state's criteria and participates in the agency's WIC training, it may enter into a vendor agreement with the state agency, thereby agreeing to comply with the state's rules and regulations.

Overseeing Vendors

As discussed earlier, WIC food benefits are provided in the form of specific foods, rather than a dollar amount of benefits (the cash value voucher/benefit is the exception). This can set up challenges for program spending, as participants are less sensitive to the price of goods and vendors can potentially take advantage of this. Therefore, states consider and monitor WIC vendors' pricing as a means of cost containment. For instance, federal law requires (1) the establishment of vendor "peer groups" and (2) additional strictures for vendors that receive over 50% of their revenue from WIC transactions. These policies, discussed further below, were added to WIC law in the 2004 reauthorization.83

Federal law requires states to establish a vendor peer group system for their WIC vendors. State agencies group vendors based on shared characteristics or criteria that affect food prices and compare prices within the group. Groups are based upon factors such as store size, geographic location, sales, and/or type of ownership. For example, large chain groceries may be grouped together as one peer group, while pharmacies may be grouped in another. States establish competitive price criteria for each peer group, with most states establishing a Maximum Allowable Reimbursement Level (MARL) or the total maximum reimbursement rate for each WIC transaction.84 When a vendor sends in a WIC voucher for reimbursement, the vendor will not be reimbursed above the MARL.

Also per the 2004 reauthorization law, states enforce additional requirements for vendors that receive over half their revenue from WIC transactions. These stores have been colloquially referred to as "WIC-only" vendors and in WIC regulations are called "above-50-percent" (A50) vendors. The 2004 law restricted A50 stores from providing incentives or other free merchandise to customers, and states are also required to limit A50 maximum reimbursements to the average of all other stores in the state.85 Not all states have A50 stores.86

At times, USDA and/or state agencies have imposed a vendor moratorium in states that have had issues managing cost containment and maintaining the integrity of existing WIC vendors. Under a vendor moratorium, no new vendors are authorized.87

Conclusion

Several aspects of the WIC program discussed in this primer—funding, eligible foods, and retail transactions—have been of interest to policymakers in the past and may continue to be in the future. Although the program has been reauthorized roughly every five years, interest in or debate over the program also arises in the context of annual appropriations deliberations. In light of budget laws' discretionary spending limits, congressional appropriators consider forecasted WIC need against other priorities. In addition to funding matters, moving forward, policymakers may be interested in overseeing the next update to the WIC food package regulations and states' transitions to EBT.

Along with the sources cited throughout the report, please see the text box below for a listing of additional resources which provide finer detail than was included in this overview.

|

Additional WIC Resources

|

Appendix A. Additional WIC Data

|

Federal Spending (in millions of dollars)a |

||||||

|

Fiscal Year |

Total Participationb (in thousands) |

Food Costs |

Nutrition Services and Administration (NSA) Costs |

Total (including other costs)c |

Per Participant Monthly Food Cost |

|

|

1989 |

4,119 |

$1,489.4 |

$416.5 |

$1,908.9 |

$30.13 |

|

|

1990 |

4,517 |

1,636.8 |

478.7 |

2,120.4 |

30.20 |

|

|

1991 |

4,893 |

1,751.9 |

544.0 |

2,298.3 |

29.84 |

|

|

1992 |

5,403 |

1,960.5 |

632.7 |

2,598.2 |

30.24 |

|

|

1993 |

5,921 |

2,115.1 |

705.6 |

2,825.5 |

29.77 |

|

|

1994 |

6,477 |

2,325.2 |

834.4 |

3,164.4 |

29.92 |

|

|

1995 |

6,894 |

2,511.6 |

904.6 |

3,429.7 |

30.36 |

|

|

1996 |

7,186 |

2,689.9 |

985.1 |

3,688.5 |

31.19 |

|

|

1997 |

7,407 |

2,815.5 |

1,008.2 |

3,837.2 |

31.68 |

|

|

1998 |

7,367 |

2,808.1 |

1,061.4 |

3,880.0 |

31.76 |

|

|

1999 |

7,311 |

2,851.6 |

1,063.9 |

3,926.0 |

32.50 |

|

|

2000 |

7,192 |

2,853.1 |

1,102.6 |

3,966.1 |

33.06 |

|

|

2001 |

7,306 |

3,007.9 |

1,110.6 |

4,132.6 |

34.31 |

|

|

2002 |

7,491 |

3,129.7 |

1,182.3 |

4,322.7 |

34.82 |

|

|

2003 |

7,631 |

3,230.3 |

1,260.0 |

4,504.7 |

35.28 |

|

|

2004 |

7,904 |

3,562.0 |

1,272.4 |

4,865.7 |

37.55 |

|

|

2005 |

8,023 |

3,602.8 |

1,335.5 |

4,968.4 |

37.42 |

|

|

2006 |

8,088 |

3,597.5 |

1,402.6 |

5,050.6 |

37.07 |

|

|

2007 |

8,285 |

3,881.1 |

1,479.0 |

5,389.1 |

39.04 |

|

|

2008 |

8,705 |

4,534.0 |

1,607.6 |

6,169.3 |

43.40 |

|

|

2009 |

9,122 |

4,640.9 |

1,788.0 |

6,451.9 |

42.40 |

|

|

2010 |

9,175 |

4,561.8 |

1,907.9 |

6,671.3 |

41.43 |

|

|

2011 |

8,961 |

5,020.2 |

1,961.3 |

7,159.6 |

46.69 |

|

|

2012 |

8,908 |

4,809.9 |

1,877.8 |

6,782.9 |

45.00 |

|

|

2013 |

8,663 |

4,497.1 |

1,881.6 |

6,463.1 |

43.26 |

|

|

2014 |

8,258 |

4,325.7 |

1,903.3 |

6,277.5 |

43.65 |

|

|

2015 |

8,024 |

4,176 |

1,922 |

6,210 |

43.37 |

|

|

2016 |

7,696 |

3,949 |

1,948 |

5,960 |

42.76 |

|

Source: USDA-FNS data, as of March 8, 2017.

a. USDA-FNS describes these data as both outlays and unliquidated obligations for the given year.

b. Average monthly participation in the given year.

c. This total includes Food and NSA as well as EBT, Infrastructure, Breastfeeding Peer Counselors, and other federal WIC costs.

Table A-2. Number and Percentage of WIC Participants Reporting Participation in Other Programs

Participant reports at certification

|

By Programs |

||

|

Program |

Number of Participants |

% of U.S. WIC Participationa |

|

TANF |

699,952 |

7.5% |

|

SNAP |

3,268,231 |

35.8% |

|

Medicaid |

6,402,851 |

68.8% |

|

TANF, SNAP, and/or Medicaid |

6.769,683 |

72.8% |

|

By Combination of Programs, Where Applicable |

||

|

Program |

Number of Participants |

% of U.S. WIC Participation |

|

TANF, SNAP, and Medicaid |

557,853 |

6.0% |

|

TANF and SNAP |

29,099 |

0.3% |

|

TANF and Medicaid |

61,692 |

0.7% |

|

SNAP and Medicaid |

2,394,853 |

25.7% |

|

TANF only |

51,308 |

0.6% |

|

|

286,426 |

3.1% |

|

Medicaid only |

3,388,453 |

36.4% |

|

Do not participate in TANF, SNAP, or Medicaid |

1,960,470 |

21.1% |

|

Not reported |

573,100 |

6.2% |

|

Total WIC Participation |

9,303,253 |

100.0% |

Source: B. Thorn, C. Tadler, and N.Huret et al., WIC Participant and Program Characteristics 2014, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, Final Report, Alexandria, VA, November, 2015, p. 34, Table III.1.

Notes: Source notes that this data likely underestimates participation in TANF, SNAP, and Medicaid. Reasons for underreporting include (1) information is recorded at time of certification and some participants are referred to these programs after certification, and (2) variations in office information systems and documentation policies.

a. Total of this column exceeds 100% because of participation in combinations of programs.

Appendix B.

Revisions of WIC Food Packages,

2003-Present

2009 Changes to the WIC Food Packages

Effective October 1, 2009, USDA significantly revised the WIC food packages. These changes were made to reflect updates and revisions in nutrition science, public health concerns, and cultural eating patterns. The revised packages provide participants with a wider variety of foods, including whole grains, fruits, and vegetables; increase incentives for breastfeeding; and allow states greater flexibility in accommodating cultural preferences of participants. Before USDA embarked on this process to update the food packages, there had not been a major revision since the 1970s.88

In 2003, USDA-FNS contracted with the Institute of Medicine (IOM) to independently review the WIC food packages, in order to align them more closely with updated nutrition science.89 IOM released its final report in 2005, recommending significant, though cost-neutral, changes to the food packages.90 IOM's major recommendations included the addition of whole-wheat bread and infant foods including fruits, vegetables, and meats; revised food quantities and food package categories; additional foods for breastfeeding women and breastfed infants; providing new optional food-substitutions (such as soy milk and tofu); and the introduction of a cash-value voucher (CVV) redeemable for a specified dollar amount of fruits and vegetables.

In December 2007, USDA-FNS published an interim final rule to update the WIC food packages. This interim rule largely included the IOM's recommendations, and state agencies were required to implement the changes in their state lists by October 1, 2009.91 While the interim final rule was in effect, USDA-FNS collected comments on its implementation, receiving over 7,500 letters. The agency published a final rule in March 2014.92

About the White Potato Policy Changes93

The description of the WIC food packages in the "Supplemental Food Package" section of this report largely reflects the March 2014 final rule. Both the interim and final rules restricted the purchase of white potatoes, but a 2015 legislative change now allows their purchase.

One of the changes in the updated food packages was the inclusion of the CVV. Based on the 2005 IOM recommendations, these interim and final regulations did not allow participants to purchase white potatoes with the CVV. IOM cited the 2005 Dietary Guidelines for Americans for starchy vegetable consumption as well as food intake data showing that white potatoes, unlike many other vegetables, were already widely consumed.

This policy proved to be controversial in Congress and related proposals were included in the 112th and 113th Congress.94 In December 2014, Congress enacted a FY2015 appropriations law that included a policy rider (Section 753 of P.L. 113-235) to change WIC's exclusion of white potatoes. The law barred USDA from excluding any vegetable (without added sugar, salt, or fat) from the WIC food packages, therefore allowing white potatoes. The provision also required USDA to conduct another review of the WIC food packages, and, based on the results of that review, white potatoes (or other vegetables) would either continue to be included or would return to being excluded. In response to the appropriations law, on December 30, 2014, FNS issued policy guidance to states for implementing the inclusion of white potatoes.95 States were required to submit implementation plans to FNS by January 30, 2015. FNS's memo states that "state agencies are expected to complete all implementation actions as soon as possible, but no later than July 1, 2015."

IOM/HMD's WIC Food Package Review: 2015-Present

Note: In 2016, the IOM was renamed the Health and Medicine Division (HMD) of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM).96

Since the 2014 final rule, USDA-FNS engaged HMD for further review and assessment of the WIC food package studies. HMD convened an expert committee and has since produced three reports, the third and final of which is expected to form the basis for FNS's next revision of the WIC food packages.97

The first, published in February 2015, was a "letter report" regarding the inclusion of the white potatoes issue (this was the review required by P.L. 113-235). The committee evaluated the 2009 regulation and, along with recommendations on data collection and study topics, recommended that USDA allow white potatoes as a WIC-eligible vegetable for purchase with the cash value voucher so long as this was consistent with the (forthcoming at that time) 2015 Dietary Guidelines for Americans.98

The second, published in November 2015, established a framework by which the HMD committee would subsequently evaluate the current WIC food packages and make findings in the final report.99

The third and final report of the series was published in January 2017; it is the HMD committee's final analysis of the current WIC food packages and includes recommendations for changes.100 In general, the committee recommends increasing the amounts of the cash value voucher, servings of whole grains, and seafood, while decreasing juice, milk, legumes, peanut butter, infant vegetables, fruits, and meats. For all food packages for women and children, the committee recommends

- increasing the dollar amount of cash value vouchers;

- adding fish;

- increasing the amount of whole grains from 16 ounces to 24 ounces; and

- reducing the amounts of juice, dairy, legumes, and peanut butter.

HMD also recommended policy changes to encourage partial breastfeeding over the exclusively formula-feeding package. Additional recommendations and the committee's rationale for its recommendations are included in the final report.

As of the date of this CRS report, USDA has not published any rules to amend the WIC food package regulations. As discussed earlier, USDA-FNS regulations based upon scientific recommendations, not the scientific recommendations themselves, govern the program's eligible foods and related issuance policies.

Appendix C. WIC Farmers' Market Nutrition Program (WIC FMNP)

The WIC Farmers' Market Nutrition Program (WIC-FMNP) was first established in 1992.101 WIC-FMNP provides grants to participating states to offer vouchers/coupons/EBT to WIC participants that may be used in farmers' markets, roadside stands, and other approved venues to purchase fresh produce.102

Not all states participate in WIC-FMNP; in FY2015, 38 states, the District of Columbia, 3 U.S. territories, and 6 Indian Tribal Organizations received WIC-FMNP grants.103 Federal funds primarily cover the program's food costs and 70% of the administrative costs for each participating state. Participating state agencies must provide program income or state, local, or private funds for the program in an amount that is equal to at least 30% of its administrative cost, with some exceptions for tribal agencies.104

In FY2015, the program covered an estimated 1.7 million recipients, and about 17,900 farmers, 3,400 farmers' markets, and 2,900 roadside stands. Participants received an average benefit of $23.105 In FY2015, total WIC-FMNP grant funding was approximately $20 million.106 FY2016 appropriations (P.L. 114-113) provided $18.5 million for WIC FMNP. These are discretionary funds, but while WIC funding is appropriated to the WIC account, WIC-FNMP funds are included in the Commodity Assistance Program account.107