Introduction

The Obama Administration requested $94.5 billion for the Department of Transportation (DOT) for FY2017, $19.5 billion (26%) more than DOT received in FY2016. The Obama Administration proposal included significant increases in funding for highway, transit, and intercity passenger rail programs. Around 75% of DOT's funding is mandatory budgetary authority drawn from trust funds; the Administration's request would have drawn a larger portion (87%) from mandatory budget authority, reducing the amount of discretionary budget authority in DOT's budget from $18.6 billion in 2016 to $12.0 billion for FY2017.

The Senate Committee on Appropriations recommended a total of $76.9 billion in new budget authority for DOT for FY2017 ($74.7 billion after scorekeeping adjustments); this is $1.8 billion (2.5%) above the comparable FY2016 amount. The committee rejected the request to reclassify some DOT expenditures as "mandatory."

On May 12, 2016, the full Senate began consideration of FY2017 appropriations for Transportation, HUD, and Related Agencies. By custom, appropriations bills originate in the House of Representatives. Because House action on the FY2017 THUD bill had not yet occurred, the Senate substituted the text of the Senate-reported FY2017 THUD bill (S. 2844) for the text of H.R. 2577, which originally contained the text of the Senate-reported FY2016 THUD bill. The Senate Appropriations Committee substitute amendment (S.Amdt. 3896) to the bill also includes as Division B the text of the Senate Appropriations Committee-reported FY2017 Military Construction, Veterans Affairs, and Related Agencies bill.

On May 24, 2016, the House Committee on Appropriations reported out H.R. 5394.

According to press reports, the Trump Administration has requested that the Essential Air Service program and the TIGER (National Infrastructure Investment) grant program be eliminated, and that the transit New Starts (Capital Investment Grants) program be reduced by $400 million from its FY2016 level, for FY2017.1

|

Continuing Resolution None of the FY2017 regular appropriations bills were enacted before the end of FY2016. Instead, Congress has approved two continuing resolutions (CRs) to provide temporary funding. The first CR provided funding for most federal agencies through December 9, 2016 (P.L. 114-223); it also contained the Military Construction and Veterans Affairs Appropriations Act for all of FY2017. The second CR, which was enacted before expiration of the first, provides funding through April 28, 2017 (P.L. 114-254). Under the terms of the CRs, funding for most programs, projects, and activities—including those administered the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD)—is continued at FY2016 levels, less an across-the-board reduction of 0.496% in the first CR and 0.1901% in the second CR. Additionally, the two CRs also provided appropriations for disaster relief grants through HUD's Community Development Block Grant program: P.L. 114-223 appropriated $500 million for grants for areas that experienced presidentially declared disasters that occurred prior to the law's enactment (including flooding in Louisiana); P.L. 114-254 appropriated $1.8 billion for areas that experienced presidentially declared disasters that occurred prior to the law's enactment (including flooding in South Carolina). For more information about the two CRs, see CRS Report R44653, Overview of Continuing Appropriations for FY2017 (H.R. 5325), coordinated by James V. Saturno, and CRS Report R44723, Overview of Further Continuing Appropriations for FY2017 (H.R. 2028), coordinated by James V. Saturno. |

Understanding the DOT Appropriations Act

DOT's funding arrangements are unusual compared to those of most other federal agencies.

Two large trust funds, the Highway Trust Fund and the Airport and Airway Trust Fund, provide 91% of DOT's budget authority (see Table 1). The scale of the funding coming from these funds is not entirely obvious in DOT budget tables, because most of the funding from the Airport and Airway Trust Fund is in the form of discretionary budget authority and so is combined with the discretionary budget authority provided from the general fund.

|

Source |

Amount |

% of Total DOT Budget Authority |

|||

|

Airport and Airway Trust Fund |

|

|

|||

|

Highway Trust Fund (including Mass Transit Account) |

|

|

|||

|

Subtotal, budget authority derived from trust funds |

|

|

|||

|

Other |

|

|

|||

|

Total budget authority |

|

|

Source: Calculated by CRS using information from Title I of Division L of P.L. 114-113, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2016.

Also, for most federal agencies discretionary funding is close or identical to total funding. But roughly three-fourths of DOT's funding is mandatory budget authority derived from trust funds. Only one-fourth of DOT's budget authority is truly discretionary authority.2 Table 2 shows the breakdown between the discretionary and mandatory funding in DOT's budget.

|

Budget Authority (BA) |

Amount |

Percent of Total |

|||

|

DOT net discretionary BA |

|

|

|||

|

DOT mandatory BA |

|

|

|||

|

DOT total budgetary resources |

|

|

Source: Comparative Statement of Budget Authority in S.Rept. 114-243.

Note: Budget authority figures in this table are net of rescissions, advance appropriations, offsetting receipts, and other adjustments.

Approximately 80% of DOT's funding is distributed to states, local authorities, and Amtrak in the form of grants (see Table 3). Of DOT's largest sub-agencies, only the Federal Aviation Administration, which is responsible for the operation of the air traffic control system and employs roughly 83% of DOT's 56,252 employees, many as air traffic controllers, has a budget whose primary expenditure is not making grants.

|

Account |

Amount |

|

Office of the Secretary: National Infrastructure Improvement (TIGER) |

$500 |

|

Federal Aviation Administration: Grants-in-Aid to Airports |

3,350 |

|

Federal Highway Administration: Federal-aid Highway Program |

42,671 |

|

Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration: Motor Carrier Safety Grants |

313 |

|

National Highway Traffic Safety Administration: Highway Traffic Safety Grants |

547 |

|

Federal Railroad Administration: Grants to Amtrak & Rail Safety Grants |

1,440 |

|

Federal Transit Administration: Formula Grants |

9,348 |

|

Federal Transit Administration: Capital Investment Grants (New Starts & Small Starts) |

2,177 |

|

Federal Transit Administration: WMATA Capital & Preventive Maintenance Grants |

150 |

|

Maritime Administration: Assistance to Small Shipyards |

5 |

|

Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration: Emergency Preparedness Grants |

28 |

|

Total Grant Accounts |

60,529 |

|

Total DOT Funding |

$75,003 |

Source: Accounts and amounts taken from Comparative Statement of Budget Authority, S.Rept. 114-243.

Note: Amounts shown in this table represent totals for grant-making accounts, except that where administrative expenses were broken out in the source table (e.g., Federal Highway Administration), they have been subtracted from the account total.

Reauthorization of Air Transportation Programs

Since most DOT funding comes from trust funds whose revenues typically come from taxes, the periodic reauthorizations of the taxes supporting these trust funds, and the apportionment of the budget authority from those trust funds to DOT programs, are a significant aspect of DOT funding. The current authorization for the federal aviation programs is scheduled to expire during FY2017. Reauthorization of this program may affect both its structure and funding level.3

DOT Funding Trend

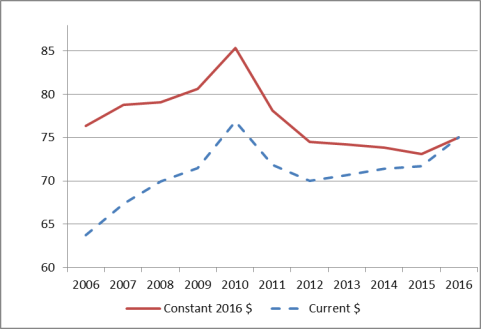

In current (nominal) dollars, DOT's nonemergency annual funding has risen from a recent low of $70 billion in FY2012 to $75 billion in FY2016. However, adjusting that funding for inflation tells a somewhat different story. DOT's inflation-adjusted funding peaked in FY2010 at $85.4 billion (in constant 2016 dollars) and declined from that point until FY2015, before rising in FY2016 (see Figure 1). Since FY2012, DOT's funding has been lower, after adjustment for inflation, than in any year during the FY2006-FY2011 period.

|

Figure 1. DOT Funding Trend (FY2006-FY2016) (in billions of dollars) |

|

|

Source: Calculated by CRS based on figures in annual House THUD Appropriations committee reports. Current dollars are converted to constant dollars using the GDP (Chained) Price Index column in Table 10.1 (Gross Domestic Product and Deflators Used in the Historical Tables: 1940-2021) in the FY2017 Budget Request: Historical Tables (https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/Historicals). Notes: Funding as shown in this chart equals discretionary appropriations plus limitations on obligations. It does not include emergency appropriations (for example, to repair storm damage) or rescissions of budget authority, rescissions of contract authority, and offsetting collections (which reduce the amount of discretionary budget authority shown as going to DOT without actually reducing the amount of funding available to DOT). |

DOT FY2017 Appropriations

Table 4 presents a selected account-by-account summary of FY2017 appropriations for DOT, compared to FY2016.

Table 4. Department of Transportation FY2016-FY2017 Detailed Budget Table

(in millions of current dollars)

|

Department of Transportation |

FY2016 Enacted |

FY2017 Request |

FY2017 House-Reported |

FY2017 Senate |

FY2017 Enacted |

|||||

|

Office of the Secretary (OST) |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Payments to air carriers (Essential Air Service)a |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

National infrastructure investment (TIGER) |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Total, OST |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Operations |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Facilities & equipment |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Research, engineering, & development |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Grants-in-aid for airports (Airport Improvement Program) (limitation on obligations) |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Total, FAA |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Total, FHWA (Federal-aid highways: limitation on obligations + exempt contract authority) |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA) |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Motor carrier safety operations and programs |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Motor carrier safety grants to states |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Total, FMCSA |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Operations and research |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Highway traffic safety grants to states (limitation on obligations) |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Total, NHTSA |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Safety and operations |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Research and development |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Railroad safety grants |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Amtrak |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Amtrak operating grants |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Amtrak capital and debt service grants |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Current passenger rail service |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Northeast Corridor Grants |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

National Network |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Total Amtrak grants |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Intercity Passenger Rail |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Rail Service Improvement Program |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Consolidated Rail infrastructure and safety improvements |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Federal-state partnership for State of Good Repair |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Restoration and enhancement grants |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Total, FRA |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

||||||||||

|

Formula grants (M) |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Capital investment grants (New Starts) |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Total, FTA |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Maritime Administration (MARAD) |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Assistance to small shipyards |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Total, MARAD |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

||||||||||

|

Subtotal |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Offsetting user fees |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Emergency preparedness grants (M) |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Total, PHMSA |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Office of Inspector General |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Saint Lawrence Seaway Development Corporation |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

||||||||||

|

Appropriation (discretionary funding) |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Limitations on obligations (M) |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Subtotal—new funding |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Rescissions of discretionary funding |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Rescissions of contract authority |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Net new discretionary funding |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Net new budget authority |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

Sources: Table prepared by CRS based on information in S. 2844 and S.Rept. 114-243.

Notes: "M" stands for mandatory budget authority. Line items may not add up to the subtotals due to omission of some accounts. Subtotals and totals may differ from those in the source documents due to treatment of rescissions, offsetting collections, and other adjustments. The figures in this table reflect new budget authority made available for the fiscal year. For budgetary calculation purposes, the source documents may subtract rescissions of prior-year funding or contract authority, or offsetting collections, in calculating subtotals and totals.

a. The Essential Air Service (EAS) program receives an additional amount in mandatory budget authority; see discussion below.

b. FY2016 totals include $31 million for the Surface Transportation Board, which was made an independent agency during FY2016 and whose funding will henceforth be provided outside the DOT budget.

Selected Issues

Overall, the Obama Administration's FY2017 budget request totaled $96.9 billion in new budget resources for DOT.4 The requested funding is $21.9 billion more than that enacted for FY2016. The Obama Administration request called for significant increases over the authorized amounts for highways, transit, and intercity rail.

According to press reports, the Trump Administration has requested $1 billion in reductions from FY2016 levels, zeroing out the Essential Air Services program (-$150 million) and the TIGER (National Infrastructure Investment) grant program (-$500 million) and reducing funding for the transit New Starts program (-$400 million).

Highway Trust Fund Solvency

Virtually all federal highway funding and most federal transit funding come from the Highway Trust Fund, whose revenues comes largely from the federal motor fuels excise tax ("gas tax"). For several years, expenditures from the fund have exceeded revenues; for example, for FY2017, revenues are projected to be approximately $42 billion, while authorized outlays are projected to be approximately $56 billion.5 Congress transferred about $143 billion, mostly from the general fund of the Treasury, to the Highway Trust Fund during the period FY2008-FY2016 to keep the trust fund solvent.6

One reason for the shortfall in the fund is that the federal gas tax has not been raised since 1993. The tax is a fixed amount assessed per gallon of fuel sold, not a percentage of the cost of the fuel sold: whether a gallon of gas costs $1 or $4, the highway trust fund receives 18.3 cents for each gallon of gasoline and 24.3 cents for each gallon of diesel. Meanwhile, the value of the gas tax has been diminished by inflation (which has reduced the purchasing power of the revenue raised by the tax) and increasing automobile fuel efficiency (which reduces growth in gasoline sales as vehicles are able to travel farther on a gallon of fuel). The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has forecast that gasoline consumption will be relatively flat through 2024, as continued increases in the fuel efficiency of the U.S. passenger fleet are projected to offset increases in the number of miles driven. Consequently, CBO expects Highway Trust Fund revenues of $40 billion to $42 billion annually from FY2017 to FY2026, well short of the annual level of projected expenditures from the fund.7

National Infrastructure Investment (TIGER Grants)

For FY2017, the Administration requested $1.25 billion for TIGER grants, the same amount as in previous years. The Senate bill would have provided $525 million, $25 million above the FY2106 amount. The Senate bill also recommended that the portion of funding allocated to projects in rural areas be increased from 20% to 30%; the same change was included in the Senate-passed bill in FY2016, but was not enacted. The House Committee on Appropriations recommended $450 million.

The Transportation Investments Generating Economic Recovery (TIGER) grant program originated in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (P.L. 111-5), where it was called "national infrastructure investment" (as it has been in subsequent appropriations acts). It is a discretionary grant program intended to address two criticisms of the current structure of federal transportation funding:

- that virtually all of the funding is distributed to state and local governments, which select projects based on their individual priorities, making it difficult to fund projects that have national or regional impacts but whose costs fall largely on one or two states; and

- that federal transportation funding is divided according to mode of transportation, making it difficult for projects in different modes to compete on the basis of comparative benefit.

The TIGER program provides grants to projects of national, regional, or metropolitan area significance in various modes on a competitive basis, with recipients selected by DOT.8

Although the program is, by description, intended to fund projects of national, regional, and metropolitan area significance, in practice its funding has gone more toward projects of regional and metropolitan area significance. In large part this is a function of congressional intent, as Congress has directed that the funds be distributed equitably across geographic areas, between rural and urban areas, and among transportation modes, and has set relatively low minimum grant thresholds ($5 million for urban projects, $1 million for rural projects).

Congress has continued to support the TIGER program through annual DOT appropriations.9 It is heavily oversubscribed; for example, DOT announced that it received a total of $10.1 billion in applications for the $500 million available for FY2015 grants.10

The U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) has reported that, while DOT has selection criteria for the TIGER grant program, it has sometimes awarded grants to lower-ranked projects while bypassing higher-ranked projects without explaining why it did so, raising questions about the integrity of the selection process.11 DOT has responded that while its project rankings are based on transportation-related criteria (e.g., safety, economic competitiveness), it must sometimes select lower-ranking projects over higher-ranking ones to comply with other selection criteria established by Congress, such as geographic balance and a balance between rural and urban awards.12

Critics argue that TIGER grants go disproportionately to urban areas. For several years Congress has directed that at least 20% of TIGER funding should go to projects in rural areas. According to the 2010 Census, 19% of the U.S. population lives in rural areas.13

As Table 5 illustrates, the TIGER grant appropriation process has followed a pattern for several years: the Administration requests as much as or more than Congress has previously provided; the House zeroes out the program or proposes a large cut; the Senate proposes an amount similar to the previously enacted figure; and the final enacted amount is similar to the previously enacted amount.

|

Budget Request |

House |

Senate |

Enacted |

|||||

|

FY2013 |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

FY2014 |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

FY2015 |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

FY2016 |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

FY2017 |

|

|

|

|

Source: Committee reports accompanying Departments of Transportation, Housing and Urban Development, and Related Agencies appropriations acts, various years.

Notes: Enacted figures do not reflect subsequent reductions due to sequester reductions or rescissions.

Essential Air Service (EAS)14

As Table 6 shows, the Obama Administration requested $150 million for the EAS program in FY2017, in addition to $104 million in mandatory funding for a total of $254 million. The Senate bill would have provided a total of $254 million, the requested amount. This was a reduction of $29 million (10%) from the FY2016 level. The requested reduction is based on an expectation of reduced costs as cost-saving measures previously enacted come into effect. The House Committee on Appropriations likewise recommended $150 million.

The program is funded through a combination of mandatory and discretionary budget authority. In addition to the annual discretionary appropriation, there is a mandatory annual authorization, $108 million in FY2016,15 financed by overflight fees collected from commercial airlines by FAA. These overflight fees apply to international flights that fly over, but do not land in, the United States. The fees are to be reasonably related to the costs of providing air traffic services to such flights.

|

FY2016 Enacted |

FY2017 Request |

FY2017 House-Reported |

FY2017 Senate |

FY2017 Enacted |

||||||

|

Appropriation |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Mandatory supplement |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Total |

|

|

|

|

|

Source: S.Rept. 114-243.

The EAS program seeks to preserve commercial air service to small communities by subsidizing service that would otherwise be unprofitable. The cost of the program in real terms has doubled since FY2008, in part because route reductions by airlines resulted in new communities being added to the program (see Table 7). Congress made changes to the program in 2012, including allowing no new entrants,16 capping the per-passenger subsidy for a community at $1,000, limiting communities that are less than 210 miles from a hub airport to a maximum average subsidy per passenger of $200, and allowing smaller planes to be used for communities with few daily passengers.17

Table 7. Essential Air Service Program: Number of Communities and Annual Appropriations, FY2008-FY2016

|

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

||||||||||

|

# of EAS communities |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Budget (millions of current $) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Budget (millions of constant 2016 dollars) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Prepared by CRS based on information from Office of the Secretary, U.S. Department of Transportation, FY2015 Budget Estimate, p. EAS/PAC -2; FY2014: H.Rept. 113-464, p. 12; FY2015: H.Rept. 114-129; FY2016: S.Rept. 114-243.

Note: Budget figures deflated using the "Total Non-Defense Outlays" column from Table 10.1—Gross Domestic Product and Deflators Used in the Historical Tables 1940-2021, Budget of the United States 2017. NA: not available.

Supporters of the EAS program contend that preserving airline service to small communities was a commitment Congress made when it deregulated airline service in 1978, anticipating that airlines would reduce or eliminate service to many communities that were too small to make such service economically viable. Supporters also contend that subsidizing air service to smaller communities promotes economic development in rural areas. Critics of the program note that the subsidy cost per passenger is relatively high,18 that many of the airports in the program have very few passengers,19 and that some of the airports receiving EAS subsidies are little more than an hour's drive from major airports.

Intercity Rail Safety

In 2008, Congress directed railroads to install positive train control (PTC) on certain segments of the national rail network by the end of 2015. PTC is a communications and signaling system that is capable of preventing incidents caused by train operator or dispatcher error.20 Freight railroads have reportedly spent billions of dollars thus far to meet this requirement, but most of the track required to have PTC installed was not in compliance at the end of 2015; in October 2015 Congress extended the deadline to the end of 2018—with an option for individual railroads to extend to 2020 with Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) approval.21

Congress provided $50 million in FY2010 and again in FY2016 for grants to railroads to help cover the expenses of installing PTC. The Obama Administration's FY2017 budget request included $875 million for the cost of PTC implementation on commuter railroad routes. The Senate recommended $199 million for PTC implementation on commuter and state-supported intercity passenger rail lines, as did the House Committee on Appropriations.

Intercity Passenger Rail Development

The Passenger Rail Reform and Investment Act of 2015 (Title XI of P.L. 114-94) reauthorized Amtrak while changing the structure of its federal grants: instead of getting separate grants for operating and capital expenses, it will now receive separate grants for the Northeast Corridor and the rest of its national network. This act also authorized three programs to make grants to states, public agencies, and rail carriers for intercity passenger rail development.

The Administration's FY2017 budget for intercity rail development requested a total of $6 billion in two new programs: a Current Rail Passenger Service Program, which would primarily fund maintenance and improvement of existing intercity passenger rail service (i.e., Amtrak), and a Rail Service Improvement Program, which would fund new intercity passenger rail projects as well as some improvements to freight rail. The funding would come from a new transportation trust fund rather than discretionary funding. The Administration has made a similar proposal annually since FY2014. The Senate bill includes $1.42 billion for Amtrak, $30 million more than its FY2016 appropriation of $1.39 billion (see Table 8), and observed that creating a new transportation trust fund was a task for authorizing committees, not appropriations committees, while acknowledging that Amtrak has a state of good repair backlog of $28 billion on the Northeast Corridor. The House Committee on Appropriations likewise recommended $1.42 billion for Amtrak.

Table 8. Federal Intercity Passenger Rail Grant Program Funding, FY2016-FY2017

(in millions of dollars)

|

Program |

FY2017 Authorized Level |

FY2016 Enacted |

FY2017 Administration Request |

FY2017 Amtrak Independent Budget Request |

H.Rept. 114-606 House-Reported |

FY2017 Senate |

FY2017 Enacted |

||||||

|

Amtrak: Northeast Corridor Grants |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Amtrak: National Network Grants |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Subtotal, Amtrak |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Consolidated Rail Infrastructure and Safety Improvement |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Federal-State Partnership for State of Good Repair Grants |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Restoration and Enhancement Grants |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Total Intercity Passenger Rail Grant Funding |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Authorized level: Title XI of P.L. 114-94; funding: S.Rept. 114-243 and H.Rept. 114-606.

Notes: Amtrak submits a budget request directly to Congress each year, separate from DOT's request for Amtrak funding. Amtrak received $1,390 million in FY2016 under a different account structure. NA ("not applicable"): these accounts were created by the FAST Act (P.L. 114-94), which was enacted after the beginning of FY2016.

The $85 million in the Senate bill, and $50 million recommended in the House bill, for intercity passenger rail grants in FY2017 in addition to the grants to Amtrak would be the first funding provided for intercity passenger rail (other than grants for positive train control implementation) since the 111th Congress (2009-2010), which provided $10.5 billion for DOT's high-speed and intercity passenger rail grant program. Since then, Congress has provided no additional funding, and in FY2011 rescinded $400 million that had been appropriated but not yet obligated.

Federal Transit Administration Capital Investment Grants

The majority of the Federal Transit Administration's (FTA's) roughly $12 billion in funding is funneled to state and local transit agencies through several formula programs. The largest discretionary transit grant program is the Capital Investment Grants program (commonly referred to as the New Starts and Small Starts program). It funds new fixed-guideway transit lines22 and extensions to existing lines. The program has four components. New Starts funds capital projects with total costs over $300 million that are seeking more than $100 million in federal funding. Small Starts funds capital projects with total costs under $300 million that are seeking less than $100 million in federal funding. Core Capacity grants are for projects that will increase the capacity of existing systems. The Expedited Project Delivery Pilot Program will provide funding for eight projects in the previous three categories that require no more than a 25% federal share and are supported, in part, by a public-private partnership.

The Capital Investment Grants program funds for any project are typically disbursed over a period of years. Much of the funding for this program each year is committed to projects with multiyear grant agreements signed in previous years.

For FY2017, the Obama Administration requested $3.5 billion for the program, $1.323 billion (61%) more than the $2.177 billion provided in FY2016. The Senate bill would have provided $2.338 billion, the authorized level, which is 7% ($161 million) above the FY2016 level. The House Committee on Appropriations recommended $2.5 billion.

A New Starts grant, by statute, can be up to 80% of the net capital project cost. Since FY2002, DOT appropriations acts have included a provision directing FTA not to sign any full funding grant agreements for New Starts projects that would provide a federal share of more than 60%. That provision was not included in the Senate bill. The House-reported bill included a provision prohibiting grant agreements where the federal share was more than 50%.

Critics of lowering the federal share provided for New Starts projects note that the federal share for highway projects is typically 80%, and in some cases is higher. They contend that the higher federal share makes highway projects relatively more attractive than public transportation projects for communities considering how to address transportation problems. Advocates of this provision note that the demand for New Starts funding greatly exceeds the amount available, so requiring a higher local match allows FTA to support more projects with the available funding. They also assert that requiring a higher local match likely encourages communities to estimate the costs and benefits of proposed transit projects more carefully, reducing the risk of subsequent cost overruns.

Grant to the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority

The Passenger Rail Investment and Improvement Act of 2008 authorized $1.5 billion over 10 years in grants to the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA) for preventive maintenance and capital grants, to be matched by funding from the District of Columbia and the states of Maryland and Virginia. Under this agreement, Congress has provided $150 million to WMATA in each of the past six years.

WMATA faces a number of difficulties. It is dealing with a backlog of maintenance needs due to inadequate maintenance investment over many years, and it has experienced several fatal incidents, most recently in January 2015, and a number of other incidents that have raised questions about the safety culture of the agency. An investigation that found numerous instances of mismanagement of federal funding has led FTA to restrict WMATA's use of federal funds. An FTA audit of WMATA's safety practices in 2015 produced many recommendations for change, and in October 2015 FTA assumed oversight of WMATA's safety compliance practices from the Tri-State Oversight Committee, the agency created by the governments of the District of Columbia, Maryland, and Virginia to oversee WMATA safety performance. The three jurisdictions are to create a new, more effective oversight entity to replace the Tri-State Oversight Committee. The National Transportation Safety Board has recommended that oversight of WMATA's rail operations be assigned to the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA), which has a long history of safety enforcement, rather than the FTA, which is primarily a grant management agency. However, Congress would have to act to give FRA authority to oversee WMATA, while FTA already has such authority.

For FY2017, the Senate bill would have provided $150 million for WMATA, while expressing frustration at the lack of progress the agency has made in improving safety with the additional funding it has been receiving. The House Committee on Appropriations likewise recommended $150 million.

Commercial Driver Hours of Service and the 34-Hour Restart Requirement

The Senate bill would have amended a provision from the FY2016 THUD act, and made a provisional change in the hours-of-service rule. The FY2016 THUD act included a provision that suspends portions of the commercial driver hours-of-service rules pending a study of their costs and benefits. These Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA) rules took effect in June 2013. Prior to that time, drivers were required to take at least 34 hours off duty after working for 60 hours in a seven-day period (or 70 hours in an eight-day period); this was referred to as the "34-hour restart requirement." The 2013 rules required that the 34-hour off-duty period cover two consecutive 1 a.m.-5 a.m. periods, and drivers were limited to taking this 34-hour "restart" once in a 168-hour (seven-day) span. If drivers work for less than 60 hours in a week, they do not have to take the 34-hour restart; for example, if a driver works eight hours every day, for a total of 56 hours in any seven-day period, that driver is not required to take a 34-hour rest period.

The purpose of the 2013 change in the hours-of-service rules was to promote highway safety by reducing the risk of driver fatigue. Under the previous rules, drivers could start their 34-hour rest period at any time of the day, and could take more than one such rest period per seven-day period. Thus a driver was able to work the maximum permitted time per day (14 hours) and take the 34-hour restart after five days, and then, after a rest period of as little as one night and two daytime periods, work 14 hours a day for another five consecutive days. FMCSA asserted that this schedule allowed a driver to work up to 82 hours over a seven-day period, which it judged to not allow sufficient rest over time to prevent driver fatigue. By requiring that the 34-hour restart period cover two 1 a.m.-5 a.m. periods, the 2012 rule was intended to allow drivers to get more sleep during the night hours, when studies indicate that sleep is most restorative (compared to sleeping during other times of the day).

A provision included in the FY2016 THUD appropriations act prohibited enforcement of the new requirements, returning the rule to what it was prior to June 2013, unless a study required by Section 133 of Division K of P.L. 113-235 (the FY2015 THUD act) finds that commercial drivers operating under the new restart provisions showed "statistically significant improvement in all outcomes related to safety, operator fatigue, driver health and longevity, and work schedules." This is slightly different than the original standard set in the FY2015 DOT appropriations act, P.L. 113-235, which set as the standard whether the study showed a "greater net benefit for the operational, safety, health and fatigue impacts of the restart provisions."

The Senate bill would have made a technical correction to the provision in the FY2016 THUD bill.23 It also would have provided that, should the results of the study be such that the rule changes implemented in 2013 are rolled back, the maximum work time for a driver would be 73 hours in a seven-day period (down from the potential 82 hours calculated by FMCSA).

FMCSA published a cost-benefit analysis in the final rule that implemented the 2013 changes, which found that the changes were cost-beneficial, but critics of the changes said that the costs were greater than FMCSA had estimated. FMCSA submitted the new study to Congress at the beginning of March 2017; it found that the 2013 rule changes did not result in significant safety benefits.