Introduction

The Home Equity Conversion Mortgage (HECM) program, administered by the Department of Housing and Urban Development's (HUD's) Federal Housing Administration (FHA), is a reverse mortgage insurance program whereby older homeowners—those age 62 and older—borrow against the equity in their homes and FHA insures lenders against potential losses associated with the loans. Unlike conventional mortgages, HECM borrowers receive payments, either periodically or in a lump sum, and the mortgages are paid off when the home is sold. If a home is sold for less than the balance of the reverse mortgage, FHA will reimburse the lender up to a maximum claim amount. Borrowers pay an up-front fee, or premium, when they enter into HECMs, and pay annual premiums based on a loan's principal balance.

The HECM program came about as a demonstration in 1988. The impetus for creating a program to help older homeowners obtain reverse mortgages was to make home equity available for aging in place—particularly for homeowners with lower incomes who may otherwise have difficulty with maintenance and other expenses. Another idea was that reverse mortgage proceeds could be used to pay for long-term care expenses. Offering government insurance was also a means to encourage private lenders to enter into the reverse mortgage market. The HECM program became permanent in 1998 and has insured nearly 1 million reverse mortgages since its creation.

The HECM program has faced financial difficulties in recent years, particularly since the economic downturn in 2008 and resulting declines in home values. Changes in the way HECMs are used, including increases in borrowers taking up-front lump-sum payments, also contributed to financial difficulties. A number of borrowers, having maximized their loans, faced loan default due to failure to pay property taxes and homeowner's insurance. The financial status of the program resulted in HUD making changes, including imposition of credit requirements for borrowers. In addition, HUD faced legal challenges in its regulatory interpretation of how non-borrowing spouses should be treated after the death of a borrower. As the result of a court decision, HUD has attempted to ensure that non-borrowing spouses are protected from foreclosure.

This report discusses the basics of how the HECM program works, including borrower eligibility, the amount that can be borrowed, and procedures for lender claims ("Basics of the Home Equity Conversion Mortgage (HECM)"); facts about HECMs and borrowers ("What Do We Know About HECMs and Borrowers?"); current issues facing the HECM program ("What Are Current Issues Surrounding HECMs?"); and the legislative history of the HECM program ("How Did the HECM Program Come About?").

Basics of the Home Equity Conversion Mortgage (HECM) Program

What Are Reverse Mortgages?

In a traditional "forward" mortgage, homeowners borrow money against the value of their homes and make monthly payments over time toward principal and interest until the mortgage is paid off. Typically forward mortgages are used to purchase homes, but homeowners may also take out second mortgages or home equity lines of credit (HELOCs) to pay for home improvements or other needs. Reverse mortgages are based on the same concept of using home equity for home maintenance and other needs, but reverse mortgages differ from forward mortgages primarily in the way that borrowers pay back the amount owed.

As with HELOCs, reverse mortgage borrowers receive money based on the equity in their home, either as a lump sum or through periodic payments. But instead of making monthly payments to repay the loan balance, a borrower is to pay back the reverse mortgage, plus accumulated interest and fees, either when they move out and sell the home or when they die and the home is sold by their estate. As a result, the term of the reverse mortgage is not fixed, unlike a forward mortgage, which extends most often for 15 or 30 years. The way in which the amount of the mortgage is determined also differs. In addition to using the home's value, the borrower's age and the interest rate are used to try to ensure that the loan balance and added interest do not outstrip the home's value.

Why Get a Reverse Mortgage?

Reverse mortgages are targeted to older homeowners and present an option for extra income as borrowers age. The ability to borrow against home equity may appeal to homeowners with lower monthly incomes and little savings. If a home is a borrower's primary asset, accessing home equity can help with everyday expenses, home improvements or modifications, or extraordinary costs that arise. Borrowers who already have home mortgage or other debt may also use reverse mortgages to pay down debt so they have fewer monthly expenses. In some cases reverse mortgages may help seniors who would otherwise not be able to remain in their homes to age in place while they remain physically able.

What Is the HECM Program?

HUD's HECM program offers FHA insurance for lenders that extend reverse mortgages to older homeowners, with borrowers paying the insurance fees. Reverse mortgages are made by private lenders, not the federal government, and for a time there was a market for reverse mortgages that did not involve government insurance. However, particularly since the 2008 economic downturn, nearly all reverse mortgages are insured through the HECM program.1 In the HECM program, HUD offers insurance to protect lenders against losses on their loans. Lenders must be approved by FHA, and the program statute and regulations determine the amount of the loans that borrowers may enter into. Borrowers pay up-front and annual insurance premiums to HUD, and if the amount of the loan exceeds the sale price at the end of its life, HUD reimburses the lender for the difference up to a maximum claim amount. (For a discussion of the maximum claim amount, see "How Much Can Be Borrowed?")

The HECM program is governed by statute and HUD regulations, but HUD may also make changes to the program via mortgagee letters.2 While the HECM statute uses the term "mortgagor" to refer to borrowers and "mortgagee" to refer to lenders, this report uses the terms borrower and lender, respectively.

Who Qualifies for HECMs?

The statute governing HECMs sets out eligibility standards for both borrowers and properties.

- Age of Borrower: To participate in the HECM program, HUD requires homeowners to be at least 62 years of age or older.3

- Type of Home: The home being mortgaged must be a one-to-four family residence, with the homeowner occupying one of the units as their primary residence.4 While most borrowers already occupy their homes, HECMs can also be used to purchase property.5 In the case of a purchase, a borrower must pay the difference between the HECM and purchase price with cash from sources approved by HUD.6

- Borrower Financial Characteristics: Until recently, the HECM program did not have income or other financial requirements for borrowers because loans are repaid from home sale proceeds. However, due to the failure of approximately 10% of HECM borrowers (representing about 54,000 loans) to pay property taxes or homeowner's insurance,7 Congress gave HUD the authority to set financial requirements via mortgagee letter.8 Effective April 27, 2015, lenders must conduct a financial assessment of new HECM borrowers.9 Borrowers' credit histories and records in paying property charges are assessed, particularly payment of property taxes and homeowner's insurance.10 This requirement was made part of final regulations, issued January 19, 2017, with an effective date of September 19, 2017.11

How Much Can Be Borrowed?

The amount that can be borrowed (or principal limit) is based on the interaction of two factors:

- The Maximum Claim Amount (MCA)—The MCA is the lesser of a home's appraised value or the HECM loan limit for the area in which the home is located.12 The maximum HECM loan limit is tied to the Freddie Mac conforming loan limit.13 The current limit is $636,150 for a single-unit residence.14 Amounts are higher for properties with 2-4 units. The MCA is the maximum that HUD will pay toward a lender's claim on insurance benefits.15

- The Principal Limit Factor (PLF)—PLFs are factors set by HUD based on borrower age, mortgage interest rate, and expected home value appreciation.16 The PLFs are percentages applied to the MCA to determine the principal limit (i.e., the amount that can be borrowed). The older the borrower and the lower the interest rate, the higher the PLF; PLFs do not change for ages above 90 years. For example, PLFs effective August 4, 2014, range from 0.130 (for a borrower age 62 at a 10% interest rate) to 0.750 (age 90 at a 3% interest rate).17 The PLF is based on the age of the youngest borrower or non-borrowing spouse, and HUD publishes separate PLFs to be used when non-borrowing spouses are under age 62. This ensures that loan amounts take into account the amount of time that both spouses are likely to remain in the home.

The Principal Limit (PL), the amount that a homeowner can borrow, is determined by multiplying the MCA and the PLF. As an example, assume a borrower who is 75 years of age and has a home valued at $200,000. The initial interest rate on the loan is 5%. The PLF in this case would be 0.614 (based on PLFs announced in August 2014), resulting in a principal limit of $122,800 ($200,000 x 0.614). The principal limit available to the borrower is reduced by any up-front fees, and, if a borrower has an existing mortgage on the property, the proceeds must be used to pay it off.

How Are Disbursements Made?

Borrowers can opt for loan payouts in a number of different ways: as a lump sum, a line of credit, in monthly payments for a term of months, in monthly payments for the borrower's lifetime, or a combination of credit line and monthly payments. Borrowers who take up-front payments (either lump sum or line-of-credit) cannot exceed an initial disbursement limit. The initial disbursement limit is currently the greater of 60% of the principal limit (as described in the previous section) or any mandatory obligations (e.g., fees, debt payoff) plus 10% of the principal limit.18 HECM regulations released on January 19, 2017, and effective September 19, 2017, provide that the FHA Commissioner will be able to adjust the initial disbursement limit, but that these percentages cannot drop below 50% or 10%, respectively.19 Total disbursements taken over time cannot exceed the principal limit. See Table 1 for more information on each payment option.

|

Type of Payment |

Method of Disbursement |

Type of Interest Rate |

Lump Sum Available? |

Limit on Lump Sum |

Percentage of Borrowers, 2016a |

|

|

Lump Sum at Closing |

Single lump sum payment |

Fixed |

Yes |

Up to the Initial Disbursement Limit.b |

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

Line of Credit |

Payments taken at borrower option. |

Adjustable |

Yes |

Up to the Initial Disbursement Limit in first 12 months and Principal Limit (PL) thereafter. |

|

|

|

Term |

Fixed monthly payments for a term of months. |

Adjustable |

No |

— |

|

|

|

Modified Term |

Combination of term of months and line of credit with a portion of the principal limit set aside for borrower draws. |

Adjustable |

Yes |

Up to the Initial Disbursement Limit in first 12 months and PL thereafter. |

|

|

|

Tenure |

Fixed monthly payments during the borrower's lifetime. The tenure option assumes payments until age 100. |

Adjustable |

No |

— |

|

|

|

Modified Tenure |

Combination of tenure payments and line of credit with a portion of the principal limit set aside for borrower draws. |

Adjustable |

Yes |

Up to the Initial Disbursement Limit in first 12 months and PL thereafter. |

|

Source: 2017 final HECM rule, 82 Federal Register 7122-7124, 24 C.F.R. §206.25 and Integrated Financial Engineering, Inc., Actuarial Review of the Federal Housing Administration Mutual Mortgage Insurance Fund HECM Loans for Fiscal Year 2016, November 15, 2016, p. 30, https://portal.hud.gov/hudportal/documents/huddoc?id=ActuarialMMIFHECM2016.pdf.

a. Total does not add to 100% due to loans for which information on disbursement type is missing.

b. The Initial Disbursement Limit is the greater of 60% of the principal limit (as described in the previous section) or any mandatory obligations (e.g., fees, debt payoff) plus 10% of the principal limit.

c. Starting with the FY2013 HECM Actuarial Report, borrowers opting for the line-of-credit and lump-sum payments are aggregated. In FY2016, 11% of HECMs were fixed-rate, meaning borrowers took lump-sum distributions at closing. Integrated Financial Engineering, Actuarial Review of the Federal Housing Administration Mutual Mortgage Insurance Fund HECM Loans for Fiscal Year 2016, November 15, 2016, pp. 30-31, https://portal.hud.gov/hudportal/documents/huddoc?id=ActuarialMMIFHECM2016.pdf.

How Much Are Mortgage Insurance Premiums?

Borrowers entering into HECMs must pay an up-front mortgage insurance premium (MIP) and an annual MIP.20

- The upfront premium depends on the amount made available to the borrower during the first 12 months of the loan:

- 0.5% when the amount available over the first 12 months of the loan is at or below 60% of the principal limit;

- 2.50% when the amount available over the first 12 months exceeds 60% of the principal limit.

- The annual MIP is 1.25% of the loan amount outstanding.

Lenders add the annual premiums to the borrower's loan balance so that the premiums accrue and are repaid as part of the loan repayment. Lenders transfer the premium payments to HUD each month.21

For a short period of time, from 2010 to 2014, HUD made available the option for a lower up-front MIP in exchange for lower loan amounts through a product called the HECM Saver.22 The upfront premium was .01% compared to 2.0% for the standard HECM product at the time.

What Obligations Do Borrowers Have?

Unlike forward mortgages, HECM borrowers do not make monthly payments toward the balance of the loan, but they still must satisfy other obligations.

Counseling: The HECM statute requires that potential borrowers go through counseling.23 Further, spouses are to participate in counseling even if they will not be on the mortgage. Prior to 2011 it was recommended that non-borrowing spouses attend counseling, but in 2011 HUD issued a mortgagee letter making it a requirement.24 The requirement has since been added to final HECM regulations issued January 19, 2017, and effective September 19, 2017.25 Counseling must be provided by a counselor who has gone through the HUD approval process, which requires employment by a HUD-approved counseling agency, initial and continued success in passing a counseling exam, and training and education.26 Counseling may occur over the phone or in person.27 Counselors are to talk with potential borrowers about options other than HECMs, financial implications of HECMs, possible consequences regarding taxes or eligibility for benefits, or consequences to the borrower's estate.28

- Principal Residence: Borrowers must stay in the home as their principal residence, meaning that it is maintained as a permanent residence where the borrowers stay for the majority of the year.29

- Good Repair: Borrowers are to keep the home in good repair.30

- Property Taxes and Homeowners Insurance: Borrowers must pay their property taxes and homeowner's insurance.31 In a forward mortgage, these payments are often added to the monthly mortgage payment to be set aside in an escrow account and paid on behalf of the borrower. However, for years this arrangement did not necessarily occur with HECMs. While borrowers always had the option for lenders to set aside these payments and add them to the balance of the loan, it was not required.32 Similarly, if a borrower failed to make payments toward taxes and insurance, the lender could always make the payments and add them to the balance of the HECM. In both cases, because many HECM borrowers take up-front lump-sum payments, adding taxes and insurance to the loan balance could exceed the amount that they are entitled to borrow. As the result of failure of some borrowers to remain current on property tax and insurance payments, in 2015, HUD issued new financial guidelines for borrowers via mortgagee letter.33 Depending on the results of financial assessments, lenders may require borrowers to deposit tax and insurance payments into a Life Expectancy Set-Aside Account for making these payments. Final regulations released on January 19, 2017 and effective September 19, 2017, continue these requirements.34

How Do HECMs End?

HECMs are designed to ensure that homeowners are not displaced.35 HECMs become due and payable when a borrower dies or conveys the property.36 In addition, HECMs may become due and payable upon the Secretary's approval if a borrower no longer resides in the home as a principal residence, has not lived in the home as a principal residence for 12 consecutive months for health reasons, or does not perform an obligation under terms of the mortgage.37 As noted, such obligations include paying property taxes and homeowner's insurance and keeping the home in good repair.38 In cases of unpaid property charges, lenders may give borrowers the opportunity to become current on payments before proceeding to foreclosure.39

When the HECM becomes due and payable, the lender is to notify HUD and let the borrower (or their estate40) know of their options. The borrower may do one of three things:41

- Pay the mortgage balance in full, including accrued interest and fees.

- Sell the home for at least the mortgage balance or 95% of the property's appraised value. (The servicer is to obtain an appraisal within 30 days of notifying the borrower or becoming aware of the borrower's death, or at the borrower's request42). When new regulations become effective on September 19, 2017, the FHA Commissioner will have discretion to set lower sales price requirements.43

- Provide a deed in lieu of foreclosure (i.e., a borrower signs the home over to the lender, typically satisfying the debt). Final regulations released January 19, 2017, and effective September 19, 2017, give the FHA Commissioner authority to establish a cash incentive for borrowers who provide a deed in lieu of foreclosure and vacate within six months of the due and payable date and generally allows nine months for the transaction to occur.44

If none of these occur, within six months of notifying the borrower of due and payable status or becoming aware of the borrower's death (or additional time as approved by HUD), the lender is required to proceed to foreclosure.45

What If HECMs Exceed Home Values?

The FHA insurance provided through the HECM program protects lenders against the risk that a loan balance exceeds the home's value. A lender's options are the following:

- Assignment: While HECMs are still active, lenders have the option to assign HECMs to HUD when a loan balance reaches 98% of the maximum claim amount (the lesser of its appraised value at the time the loan was extended or the FHA loan limit).46 This may occur over long loan terms where adjustable interest rates rise significantly, for example, or where taxes and insurance payments are added to the loan balance. However, assignment may not occur if the mortgage is due and payable for reasons described in the previous section. When lenders assign mortgages to HUD, they make a claim for the outstanding balance up to the maximum claim amount.47

- Claims: After HECMs become due and payable, if a home is not sold for enough to cover the cost of the HECM loan balance, lenders can make a claim to HUD for the difference, up to the maximum claim amount.48 What may be included in the claim amount depends on the way in which the property was disposed of—purchased by the lender, sold to another party at foreclosure, or sold by the borrower (or borrower's estate).49

What Consumer Protections Exist?

From the time federal involvement in home equity conversion was contemplated, advocacy groups and Members of Congress have made efforts to ensure that borrowers understand reverse mortgages and that protections exist to prevent exploitation.50 As initially enacted in the Housing and Community Development Act of 1987 (P.L. 100-242), HECMs required that borrowers undergo counseling and that lenders make certain disclosures. Over the years, additional consumer protection provisions have been added to the law.

- As part of the FY1999 HUD appropriations act (P.L. 105-276), Congress required additional disclosures regarding charges included as part of HECMs, directed the HUD Secretary to work with consumer groups about consumer education, and gave the HUD Secretary discretion to impose restrictions ensuring that consumers do not pay unnecessary or excessive costs for obtaining the loans.

- The Housing and Economic Recovery Act (HERA, P.L. 110-289) prohibited HECM counselors from being associated with lenders or entities selling financial or insurance products, prevented lenders from selling financial or insurance products directly or requiring their purchase, and limited loan origination fees that can be charged.

- HERA also removed a provision in the HECM statute (added as part of the American Homeownership and Economic Opportunity Act of 2000, P.L. 106-569) that had allowed up-front mortgage insurance premiums to be waived when borrowers purchased long-term care insurance.

What Do We Know About HECMs and Borrowers?

HECM program loans are a very small portion of the mortgage market; at the program's peak in FY2009, about 115,000 new loans were insured out of 1.8 million FHA single family loans insured in the same year.51 By comparison, the total number of mortgages originated in calendar year 2009 was nearly 9.4 million.52 By FY2015, the number of HECMs in the year was about 58,000.53 The program has insured nearly 1 million loans since its inception.54 While the HECM statute technically limits the total number of HECMs that HUD can insure to an aggregate of 275,000,55 Congress has waived the limitation in appropriations acts.56

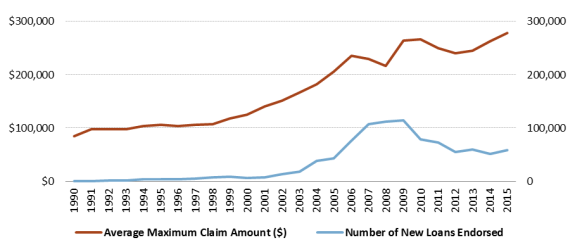

The average maximum claim amount, representing the ceiling on HUD's insurance obligation for a loan (and generally the appraised value of a home), was less than $100,000 in the early years of the HECM program, and was just over $275,000 in FY2015.57 (See Figure 1 for the number of new loans endorsed in each year and average maximum claim amounts.)

|

Figure 1. Number of HECM Loans Endorsed and Average Maximum Claim Amount FY1990-FY2015 |

|

|

Source: Data from FY1990 to FY2012 are from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Home Equity Conversion Mortgage Characteristics, September 2012, http://portal.hud.gov/hudportal/documents/huddoc?id=hecm0912.xls. HUD stopped making the data publicly available after FY2012, so FY2013-FY2015 data are from the HECM Actuarial Reports. |

Since the inception of the HECM program, borrowers have gotten younger, the way in which borrowers choose to take disbursements has changed, and more borrowers appear to use HECMs to pay off existing mortgages and other debt.

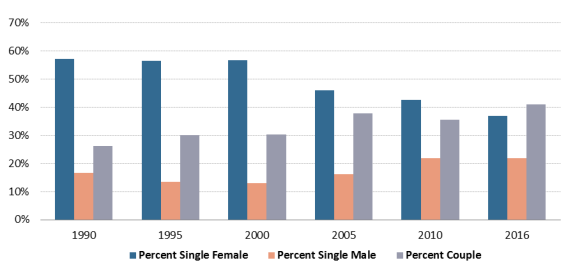

The average age of HECM borrowers has declined since the program's inception. In 1990, shortly after the HECM program was enacted as a demonstration, the average borrower age was about 77. Since then it has gradually declined, and was age 73 in FY2016.58 The gender of HECM borrowers has also changed over the years. Females made up more than 50% of HECM borrowers (compared to men and multiple borrowers/couples) through FY2002, but their percentages declined as the percentages of both male borrowers and couples increased. FY2013 was the first year in which couple borrowers exceeded female borrowers. By FY2016, couples made up 41% of borrowers compared to 37% for females. Male borrowers also increased from the early years of the program, hovering around 15% in the beginning and rising to nearly 22% in FY2016.

The growing trend in couples borrowing could be due to the fact that borrowers are getting younger. In addition, increases in both male and couple borrowing could be related to treatment of non-borrowing spouses. Until recently, it was not uncommon for the younger spouse (generally women) to be removed from the deed and mortgage to increase the amount that could be borrowed (by increasing the principal limit factor). This may have accounted for some of the growth in male borrowers. Then, HUD's inclusion of the age of non-borrowing spouses in calculating the amount of the loan (starting in 2014) may account for the most recent uptick in couple borrowing. (See Figure 2 for HECM borrower gender distribution for select years from FY1990 to FY2016.)

|

Selected Years from FY1990-FY2016 |

|

|

Source: Data from FY1990 to FY2012 are from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Home Equity Conversion Mortgage Characteristics, September 2012, http://portal.hud.gov/hudportal/documents/huddoc?id=hecm0912.xls. HUD stopped making the data publicly available after FY2012, so later data are from the HECM Actuarial Reports. Notes: HUD data prior to FY2013 did not break out missing data. The FY2016 HECM Actuarial Report reported that data were missing for 0.39% of borrowers. |

There is evidence that the credit situations of HECM borrowers may be less secure now than in earlier years of the program. In general, consumer debt, including mortgage debt, increased for homeowners age 65 and older during the 2000s.59 In 2001, 22% of older homeowners had mortgage debt with a median amount of $43,400.60 By 2011 the percentage had grown to 30% with a median mortgage amount of $79,000.61 According to a 2011 survey of HECM counselors, a growing number of potential HECM borrowers gave their reason for pursuing a reverse mortgage as paying off debt—67% compared to 51% in a similar survey taken in 2006.62 Of those counseled, 79% had existing debt, 40% of which was mortgage debt.63 HUD has also acknowledged the increase in borrowers with existing property debt.64

Growing debt may be a reason behind the way in which borrowers take HECM disbursements. Until changes in 2014 that limited the initial draws for fixed-rate lump-sum or line-of-credit HECMs, borrowers took out large percentages of their HECM loans up front. For example, in each year from FY2010-FY2013, more than 70% of HECM borrowers withdrew between 80% and 100% of their principal limit during the first month of the loan.65 In the early years of HECM loans, most borrowers either chose to take distributions as a line-of-credit, or combined term and tenure payments with lines of credit.66 The changed disbursement preference can be traced to the advent of fixed interest rate HECMs. Fixed interest rate HECMs structured as closed-end loans began to become common in 2008, largely due to the ease of securitizing fixed-rate products, with HUD releasing guidance clarifying that lenders could offer fixed interest rate loans.67 In fixed interest rate transactions, lenders require that borrowers take the entire amount of the loan up front as a lump sum (if fixed-rate products allowed future draws, lenders would have to absorb the cost of interest rate increases). Prior to 2009, lump sum payments made up less than 10% of HECMs; by the end of 2009 they made up nearly 70%.68 Today, nearly all HECM borrowers choose to use either the closed-end lump-sum option or, using a line of credit, effectively withdraw most of the balance up front. For more information about limits on initial disbursements, see "How Are Disbursements Made?"

What Are Current Issues Surrounding HECMs?

Financial Status of HECMs

The HECM portfolio has shown volatility for the last eight years, the span during which it has been subject to actuarial review. (HECMs became part of FHA's Mutual Mortgage Insurance (MMI) Fund in 2009, which made the loan portfolio subject to actuarial review.69) Since 2009, the estimated economic value of the HECM loan portfolio has fluctuated between positive and negative.70 When the economic value is negative, this means that the combination of funds that the HECM program has on hand, plus mortgage insurance premium revenue expected in the future from HECMs existing at the time of the analysis, are not expected to be enough to cover anticipated future claims on existing HECMs (assuming no loans are insured going forward).

HUD began to make changes to the HECM program to increase its financial stability when, in FY2013, the FHA MMI Fund required a mandatory appropriation of $1.7 billion—largely due to the status of HECMs—and an additional $4 billion was transferred from the MMI capital account to the HECM financing account.71 Despite changes to the program, most recently, the FY2016 HECM actuarial review reported an economic value of negative $7.7 billion.72 This section discusses the reasons behind financial instability and actions taken by Congress and HUD to shore up the HECM portfolio.

Reasons for Financial Instability

Over the years, a variety of factors have contributed to estimates of negative economic value for the HECM portfolio. For example, at the time of the FY2012 Actuarial Review, the year of the first negative estimate exceeding $1 billion (the estimate was negative $2.8 billion), contributing factors included declines in home values after the housing market decline that began in 2008; longer loan life than expected; an increase in the number of homes conveyed to FHA (versus retained and sold by the borrower or lender), meaning that FHA had to maintain and market the homes; and an increasing number of borrowers who withdrew the maximum lump sum payment at loan closing rather than receiving smaller amounts.73 This latter change increased the risk that principal balances could eventually outstrip home values. Another (and similar) issue was that as of 2012, approximately 10% of HECM borrowers (representing about 54,000 loans) had failed to pay property taxes or homeowner's insurance and were reportedly at risk of losing their homes.74 In large part, lenders paid the outstanding debts, adding them to borrower loan balances.75 For many borrowers, adding taxes and insurance to the loan balance exceeded the amount that they were entitled to borrow and further increased chances of additional claims.

The FY2016 actuarial review had the largest negative estimate of economic value for the current year to date: negative $7.7 billion. Newly available FHA data for the FY2016 analysis resulted in changed assumptions about the HECM portfolio contributing to the negative estimate. HECM home sales prices were not as high as had been estimated in previous actuarial reports due to the "discount" in price of HECM properties relative to market prices. The discount is the difference in sales price of HECM properties relative to similar non-HECM homes and is due to factors such as failure to maintain the properties.76 In addition, new FHA data also showed that there were higher costs than previously estimated for lenders and FHA to maintain and sell properties.77 When the costs to maintain and sell homes increase, so do costs to FHA.

Actions Taken to Restore Financial Stability

In August 2013, Congress enacted the Reverse Mortgage Stabilization Act of 2013 (P.L. 113-29) to give HUD the ability to use notices or mortgagee letters to "to improve the fiscal safety and soundness of the reverse mortgage program." Previously, a notice and comment period had been required, which HUD indicated was too time-consuming a process to allow timely changes to be made to protect the HECM insurance fund.78 After enactment of P.L. 113-29, HUD initiated a number of program changes, some of which are included in final regulations released on January 19, 2017, and that will be effective September 19, 2017.

- In 2013, HUD limited lump sum payments to borrowers by making them available only for HECMs extended under a product existing at the time called the HECM Saver. The HECM Saver offered lower up-front mortgage insurance premiums (0.01%) in exchange for low loan amounts.79

- Later in 2013, HUD eliminated the HECM Saver and applied new lump sum payment limits to all HECMs. HUD reduced the amount that borrowers could draw during the first 12 months of the loan and increased mortgage insurance premiums if initial draws exceed 60% of the principal limit.80 (See "How Much Can Be Borrowed?")

- While lenders have never allowed future draws on fixed interest rate HECMs, HUD acknowledged that the possibility of this occurring presented a risk to the stability of the insurance fund. So in 2014 HUD stated that it will only insure fixed rate loans where all proceeds are taken up front in a lump sum without any possibility of future draws.81

- As of April 27, 2015, HUD requires that borrowers' credit histories and their ability to pay taxes and insurance be taken into account in approving HECMs.82 This had not previously been required, unlike with many forward mortgages where credit history and ability to repay have often been a component of eligibility. FHA issued a Financial Assessment and Property Charge Guide along with a Mortgagee Letter containing details about what lenders should consider in determining eligibility.83 Borrowers may be required to set up a "life-expectancy set-aside account," (LESA) an escrow account where a portion of funds that would otherwise be proceeds to the borrower are deposited to ensure payments are made.84 Further, in final regulations effective September 19, 2017, the FHA Commissioner will have the authority, through Federal Register notice, to create an incentive for borrowers to voluntarily set up life-expectancy-set-aside accounts.85

- HUD regulations published on January 19, 2017, and effective September 19, 2017, provide that HECM insurance reimbursement for lenders' property charge advances (e.g., payments made on behalf of borrowers for property taxes, insurance, etc.) will be limited to two-thirds of the total payments made. The two-thirds reimbursement will only apply to HECMs with case numbers assigned on or after September 19, 2017.86

Spouses of Borrowers

For a number of years, there was uncertainty surrounding the way in which spouses of HECM borrowers who themselves were not a party to the loan (i.e., non-borrowing spouses) would be treated when the borrowing spouse passed away. The confusion centered on HUD interpreting the term "homeowner" in section 1715-20(j) of the code—"Safeguards to prevent displacement of homeowner"—in a way that a federal district court ruled was at odds with the statute. For years, HUD interpreted the statute to require that HECMs become due and payable upon the borrower's death, with the result that numerous non-borrowing spouses found themselves facing foreclosure or full loan repayment when their spouses passed away. However, due to the court decision invalidating HUD's interpretation of the statute, HUD has changed the way in which non-borrowing surviving spouses are treated to ensure that, in most cases, they may remain in the home.87

Protections for non-borrowing spouses exist in both mortgagee letter and HECM regulations released on January 19, 2017, and effective September 19, 2017.

- Loans Entered into Prior to August 4, 2014: HECM Mortgagee Letter 2015-15 gives lenders the option to assign HECMs to HUD, with HUD deferring payment of the HECM, as long as the non-borrowing spouse fulfills certain conditions.88 Among the conditions that non-borrowing spouses must fulfill are (1) being married at the time of HECM extension and at borrower death, or being in a committed relationship but prohibited from marrying at the time the borrower entered into the HECM and later married, (2) residing and continuing to reside in the property as a principal residence, and (3) obtaining marketable title within 90 days of the borrower's death or the ability to remain in the property for life. To qualify, the HECM cannot be due and payable for reasons other than the borrower's death at the time of assignment, and non-borrowing spouses must keep up with property tax and insurance payments. If HECMs are ineligible for assignment or a lender chooses not to assign the loan to HUD, then foreclosure should proceed within six months of the borrower's death.

- Loans Entered Into On or After August 4, 2014: Originally provided via mortgagee letter, HUD released final HECM regulations on January 19, 2017, and effective September 19, 2017, that include provisions to protect non-borrowing spouses and to ensure that, going forward, the ages of non-borrowing spouses are taken into account when determining loan levels.89 Non-borrowing spouses may remain in the home as long as they satisfy certain qualifying attributes and maintain additional criteria during the deferral period. The qualifying attributes are (1) borrower and non-borrower were spouses at the time the loan was entered into and remained spouses through the duration of the borrower's lifetime; (2) the relationship as a non-borrowing spouse was disclosed at the time of mortgage origination and was included in the mortgage documents; and (3) the non-borrowing spouse occupied and continues to occupy the house as a principal residence. If these qualifying attributes fail to be met, then the loan becomes due and payable. Additional criteria required during the deferral period provide that the non-borrowing spouse must (1) establish legal ownership within 90 days; (2) continue to satisfy HECM obligations; and (3) ensure that the HECM does not become due and payable.

How Did the HECM Program Come About?

While reverse mortgages were made privately on a small scale starting in the 1970s,90 the initial federal government involvement occurred as a one-time grant through the Administration on Aging (AoA), within the Department of Health and Human Services, called the Home Equity Conversion Project. AoA awarded a grant to researchers in the State of Wisconsin to conduct a feasibility study for reverse mortgages.91 The Wisconsin Department of Aging had already begun a "Reverse Mortgage Study Project" in 1978. It used the AoA funding to conduct consumer research and provide technical assistance on six pilot projects across the country that experimented with lending against home equity for seniors.92

About the same time that the Home Equity Conversion Project was underway, as part of the 1980 White House Conference on Aging, the conference's Mini-Conference on Housing for the Elderly released a report with recommendations for providing housing assistance as individuals age. One of the recommendations was to develop a way in which seniors could use home equity to supplement their income; the reverse mortgage was one of the options proposed.93 In 1982, partially in response to the mini-conference recommendations, the Senate Special Committee on Aging held a hearing on the issue of home equity conversion,94 and later released an informational report about options for converting home equity into income.95

The HECM Program from 1988 to 2000

Legislation to enact a home equity conversion mortgage program was introduced in the 98th and 99th Congresses, but no laws were enacted.96 In the subsequent Congress, in 1988, the HECM program was enacted as a demonstration, the Home Equity Conversion Mortgage Insurance Demonstration (P.L. 100-242). The program was based on a combination of provisions from both a Senate-passed bill (S. 825) and a House-passed bill (H.R. 4) that were brought together in conference.97 Based on hearings and congressional committee reports leading up to the program's enactment, the rationale for creating a reverse mortgage insurance program was to help seniors with lower incomes, and who had available home equity, remain in their homes and pay for expenses that they might not otherwise be able to afford.98

In addition, both of the relevant House and Senate committees discussed in their respective reports regarding HECMs the need for government insurance as a means to encourage private lenders to enter into reverse mortgages. For example, the House Committee on Banking, Finance, and Urban Affairs, in its report accompanying H.R. 4, explained its inclusion of the HECM demonstration:

This demonstration program is designed to encourage private lenders to provide home equity conversion mortgages because many financial institutions have been hesitant to enter the field due to laws that do not recognize these types of mortgage instruments as well as the fact that the concept itself is relatively new.99

The committee report went on to cite with approval the fact that the bill contained protections for borrowers such as required counseling and the prohibition on involuntary displacement. The Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs report accompanying S. 825 contained similar language.100

P.L. 100-242 provided that HUD could insure up to 2,500 HECMs from the date of the demonstration program's enactment through September 30, 1991. The program had the following characteristics:

- Only those owning single-unit homes qualified (i.e., properties with two or more units did not qualify).

- Borrowers were allowed to prepay the mortgage without penalty.

- The law allowed for a fixed or variable interest rate.

- Homeowners were not liable for any balance outstanding on the mortgage after sale.

- The law included the requirement that borrowers receive counseling from a third party (not the lender) regarding other financial options besides a reverse mortgage, financial implications of a reverse mortgage, and "a disclosure that a home equity conversion mortgage may have tax consequences, affect eligibility for assistance under Federal and State programs, and have an impact on the estate and heirs of the homeowner."

- The law also required that the mortgage contract contain a provision that borrowers need not repay the balance of the loan until death or sale of the home.

The HECM program continued as a demonstration for about 10 years. During that period, the program was extended three times, through September 30, 2000, and the maximum number of mortgages that HUD could insure was increased to 25,000 in 1990 (P.L. 101-508), to 30,000 in 1996 (P.L. 104-99), and shortly thereafter to 50,000 (P.L. 104-120). HUD also released three reports during this time evaluating the HECM demonstration program, as required by the statute.101

The only substantive change to the HECM program during the demonstration period was made as part of the Housing Opportunity Program Extension Act of 1996 (P.L. 104-120). The law expanded the program to allow FHA insurance to cover 1-4 family residences.

The FY1999 Departments of Veterans Affairs and Housing and Urban Development, and Independent Agencies Appropriations Act (P.L. 105-276) removed the demonstration status from the HECM program and increased the number of mortgages that could be insured to 150,000. The law also

- directed the HUD Secretary to consult with consumer groups, industry representatives, and representatives from counseling organizations to "identify alternative approaches to providing consumer information" to potential HECM borrowers;

- authorized (from FY2000-FY2003) up to $1 million of the amount appropriated for HUD's Housing Counseling program to be used for HECM counseling and consumer education;

- expanded disclosure requirements, requiring that borrowers know all charges involved in the mortgage, including those for estate planning and financial advice, and which charges are required for obtaining the mortgage and which are not; and

- gave the HUD Secretary the authority to put in place restrictions to ensure that a borrower "does not fund any unnecessary or excessive costs for obtaining the mortgage, including any costs of estate planning, financial advice, or other related services."

Changes to the HECM Program Since 2000

The American Homeownership and Economic Opportunity Act of 2000 (P.L. 106-569):

- The law provided that borrowers could refinance existing HECMs. As part of the refinancing, they could receive credit for the up-front premium paid on the previous HECM, as well as waive counseling if the previous HECM had been made within the last five years. The law also gave the HUD Secretary the authority to set limits on the origination fee for the subsequent HECM.

- Owners of units in housing cooperatives were made eligible for HECMs.

- The law allowed the up-front mortgage insurance premium to be waived in instances where borrowers used the amount borrowed from the reverse mortgage to purchase long-term care insurance.

FY2007 Department of Defense Appropriations Act (P.L. 109-289):

- The law expanded the aggregate number of mortgages that can be insured to 275,000, and as of the date of this report, the limit remains at that number. Note that this limitation is waived in appropriations acts.

The Housing and Economic Recovery Act of 2008 (P.L. 110-289):

- The law strengthened the counseling requirement for HECM borrowers. Third party housing counselors cannot be associated (directly or indirectly) with the loan originator or servicer, or with an entity involved in selling annuities, long-term care insurance, or other financial or insurance products.

- The HUD Secretary was given authority to use a portion of mortgage insurance premiums to fund housing counseling.

- Mortgage originators were prevented from participating in the sale of insurance or financial products, or to establish firewalls within the company to ensure that there is no incentive to sell insurance or financial products to borrowers.

- Lenders were prohibited from requiring borrowers to purchase insurance and financial products as part of the reverse mortgage transaction.

- The provision that allowed the up-front mortgage insurance premium to be waived when borrowers purchased long-term care insurance (added as part of P.L. 106-569) was removed.

- The law limited the amount of origination fees that can be charged.

- HECMs were allowed to be used to purchase a one- to four-family home.

The Reverse Mortgage Stabilization Act of 2013 (P.L. 113-29):

The law gave HUD the authority to establish requirements via notice or mortgagee letter (rather than regulation) regarding the fiscal safety and soundness of the HECM program.