Introduction

Member-to-Member correspondence has long been used in Congress. Since early House rules permitted measures to be introduced only in a manner involving the "explicit approval of the full chamber," Representatives needed permission from other Members to introduce legislation.1 A common communication medium for soliciting support for this action was a letter to colleagues. For example, in 1849, Representative Abraham Lincoln formally notified his colleagues in writing that he intended to seek their authorization to introduce a bill to abolish slavery in the District of Columbia.2

The use of the phrase "Dear Colleague" has been used since at least the early 20th century to refer to a letter widely distributed among Members. In 1913, the New York Times included the text of a "Dear Colleague" letter written by Representative Finley H. Gray to Representative Robert N. Page in which Gray outlined his "conceptions of a fit and proper manner" in which Members of the House should "show their respect for the President" and "express their well wishes" to the first family.3 In 1916, the Washington Post included the text of a "Dear Colleague" letter written by Representative William P. Borland and distributed to colleagues on the House floor. The letter provided an explanation of an amendment he had offered to a House bill.4

Today, a "Dear Colleague" letter is official correspondence sent by a Member, committee, or officer of the House of Representatives or Senate and that is widely distributed to other congressional offices.5 These letters are named for their the most common opening salutation—"Dear Colleague"—and are often used to encourage others to cosponsor, support or oppose legislation; collect signatures on letters; invite Members to events; update congressional offices on administrative rules; and provide general information. "Dear Colleague" letters may be circulated through internal mail, distributed on the chamber floor, or sent electronically.6

"Dear Colleague" letters are now primarily sent electronically through the internal networks in the House and Senate. The use of internal networks has, for the most part, supplanted paper forms of the letters, as electronic dissemination has increased the speed, reduced the cost, increased the volume, and facilitated the process of distributing "Dear Colleague" letters.

Since 2009, the House has utilized a web-based distribution system—the e-"Dear Colleague" system.7 This system allows Members and staff to tag "Dear Colleague" letters with policy issue terms, send letters with graphics and hyperlinks, and subscribe to "Dear Colleague" letters based on issue terms. Additionally, the e-"Dear Colleague" system contains a searchable archive of all letters sent after 2008.8 In the Senate, no centralized electronic "Dear Colleague" distribution system exists. Instead, individual offices often maintain their own distribution lists. Additionally, some "Dear Colleague" letters have been collected by the Committee on Rules and Administration and are available on the Senate's internal website—Webster.9

This report provides a comparative analysis of how the use of the e-"Dear Colleague" system in the House of Representatives has changed between the 111th Congress (2009-2010) and the 113th Congress (2013-2014). This report provides an overview of the data and methodology used to evaluate "Dear Colleague" letter usage, discusses the characteristics and purpose of "Dear Colleague" letters, and discusses questions for Congress and observations on the use of "Dear Colleague" letters as a form of internal communications.

Data and Methodology

"Dear Colleague" letters have been sent electronically in the House of Representatives since 2003, when the House launched an email-based system to distribute "Dear Colleague" letters. This email system was replaced by the web-based e-"Dear Colleague" system beginning in 2009. For analysis of "Dear Colleague" letters in this report, data were divided into two datasets.

To evaluate the overall volume of dear colleague sent since 2003, the first dataset, which contains the total number of "Dear Colleague" letters sent electronically between January 2003 and December 2014, was utilized. For "Dear Colleague" letters sent electronically between January 2003 and December 2008, data were collected in December 2010 from the archive of email letters that were contained in the Legislative Information System (LIS).10 For letters sent between January 2009 and December 2014, the e-"Dear Colleague" system was used. In all cases, the data do not include paper "Dear Colleague" letters or electronic "Dear Colleague" letters that were not sent through the House's email "Dear Colleague" system or the e-"Dear Colleague" system. It is not known what percentage of "Dear Colleague" letters was sent by email rather than through the internal mail system in the House.

The second dataset comprises all "Dear Colleague" letters sent through the e-"Dear Colleague" system during the 111th Congress and the 113th Congress. The combined dataset allowed for a detailed examination of how the e-"Dear Colleague" system was used by Members, committees, and officers of the House in two specific congresses. Additionally, this dataset allowed a comparison of how use of the system has evolved since the 111th Congress. Analysis of the letters in the 111th Congress was originally conducted by CRS in September 2011.11 Analysis of the "Dear Colleague" letters in the 113th Congress was conducted by CRS in partnership with a capstone class at the Bush School of Government and Public Service at Texas A&M University during the 2015-2016 academic year.

For the second dataset, each letter included the date it was sent, the letter's associated issue terms, the sending office, the letter's title, and any associated bill or resolution number. For the 111th Congress, the data were downloaded from the House e-"Dear Colleague" website. For the 113th Congress, data were provided to CRS by the Chief Administrative Officer (CAO) of the House. These data were then coded for the letter's purpose, the type of office that sent the letter (Member, committee, House officer, or congressional commission), the political party of the sender (if relevant), and the final disposition of legislation associated with the letter (if any).12 In total 72,254 "Dear Colleague" letters were coded—31,767 from the 111th Congress and 40,487 letters from the 113th Congress.

"Dear Colleague" Volume

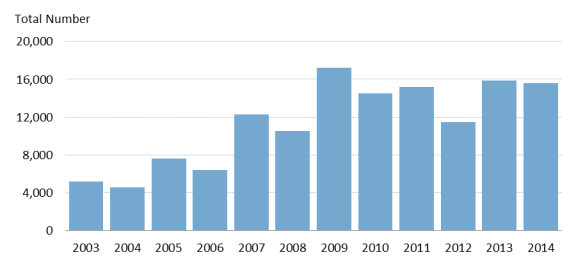

Overall, the number of "Dear Colleague" letters sent electronically between 2003 and 2014 has generally increased over time, even though in some years the total number of letters sent declined from the previous year (Figure 1). Using the first dataset to examine the volume of "Dear Colleague" letters sent electronically, Figure 1 shows the number of electronic "Dear Colleague" letters sent annually from 2003 to 2014.13 In those years, a total of 136,331 "Dear Colleague" letters were sent.

|

Figure 1. Total Electronic "Dear Colleague" Letters, 2003-2014 |

|

|

Source: Legislative Information System (LIS) of the U.S. Congress and http://e-dearcolleague.house.gov. Data for the email-based system used between January 2003 and December 2008 were compiled by Jennifer Manning, information research specialist, Knowledge Services Group, Congressional Research Service. |

Figure 1 suggests fewer "Dear Colleague" letters are sent during even-numbered years than during odd-numbered years. This effect is most pronounced during presidential election years, particularly 2008 and 2012. Those years saw the largest decrease compared to the previous year in "Dear Colleague" letters sent.

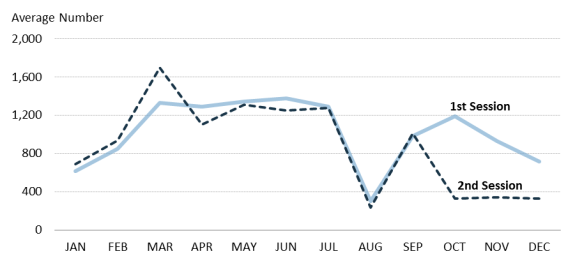

Examining the number of electronic "Dear Colleague" letters sent each year provides an overall picture of the increased use of email- and web-based distribution to send "Dear Colleague" letters. Examining the average number of letters sent each month provides a more detailed look at the distribution of "Dear Colleague" letters over an entire Congress and complements the analysis of the broader trends shown in Figure 1. At this more granular level, Figure 2 shows the average number of "Dear Colleague" letters sent each month over the six Congresses that occurred from 2003 to 2014, broken out by session.14

|

Figure 2. Monthly Electronic "Dear Colleague" Letters |

|

|

Source: Legislative Information System (LIS) of the U.S. Congress and http://e-dearcolleague.house.gov. Data for the email-based system used between January 2003 and December 2008 were compiled by Jennifer Manning, information research specialist, Knowledge Services Group, Congressional Research Service. |

As Figure 2 shows, the pattern of "Dear Colleague" letters generally aligned with the overall congressional work schedule. Between January and September, the number of "Dear Colleague" letters sent in the first and second sessions was fairly similar. After September, however, the pattern in the average number of "Dear Colleague" letters sent diverged between the first and second sessions. The volume in September was moderately high in both sessions, but there was a decline beginning in October of the second session.

In August, there was a significant reduction in the number of "Dear Colleague" letters sent in both sessions. Primarily, this reduction likely occurred because of the month-long district work period (recess) that is normally scheduled. As a result of the district work period, Members are likely more focused on their constituent service duties and concerns external to House operations during those periods than on introduction of legislation and public policy.

The data also suggest two additional trends. First, the data in Figure 1 that show a decline in the number of "Dear Colleague" letters sent during election years, especially presidential election years, suggest that the flow of internal communications declines when congressional workload declines. As Figure 2 further shows, the average number of "Dear Colleague" letters declines when Congress is in a traditional district work period.

Who Sends "Dear Colleague" Letters?

The analysis in this and subsequent sections uses the second dataset of "Dear Colleague" letters: those sent in the 111th and 113th Congresses using the e-"Dear Colleague" system. While Members, House officers, committees, and House commissions may send "Dear Colleague" letters, Members accounted for the vast majority of all letters sent in both the 111th and 113th Congresses, followed by committees, officers, and commissions. Additionally, in the 113th Congress, House leaders (e.g., the Speaker of the House or the minority leader) sent letters from their leadership office though the dataset reflected only small numbers of letters from these offices. The dataset for the 111th Congress did not include categories for senders from leadership offices (e.g., majority leader, minority leader). Table 1 shows the breakdown by sender of "Dear Colleague" letters in the 111th and 113th Congresses.

|

111th Congress |

113th Congress |

|||

|

Sender |

Total |

Percentage |

Total |

Percentage |

|

Member |

26,380 |

94.0% |

38,412 |

94.9% |

|

Committee |

1,396 |

5.0% |

1,399 |

3.5% |

|

Officer |

158 |

0.6% |

343 |

0.8% |

|

Commission |

134 |

0.5% |

316 |

0.8% |

|

Leadershipa |

— |

— |

17 |

0.0% |

|

Total |

28,068 |

100.0% |

40,487 |

100.0% |

Source: CRS and Bush School of Government and Public Service compilation of data from http://e-dearcolleague.house.gov. Numbers may not add to 100% due to rounding.

Note:

a. Leadership includes the Speaker of the House, the House majority leader, the House minority leader, and the majority and minority whips.

As Table 1 shows, Members send an overwhelming majority of "Dear Colleague" letters. This finding is expected, as the majority of "Dear Colleague" letters are sent to request legislative cosponsors. While committees account for between 3.5% and 5.0% of "Dear Colleague" letters, it is possible that the number of "Dear Colleague" letters dealing with committee activities is greater, since committee members may have sent "Dear Colleague" letters in their own name rather than under a committee's banner. In this case, a letter would have been counted as a Member letter.

There is variation by party in who sends "Dear Colleague" letters through the e-"Dear Colleague" system. In the 111th Congress, 82.5% of all Member letters were sent by Democrats compared with 17.5% by Republicans. At that time, these numbers were not descriptively representative of the overall House membership for the 111th Congress, which was 59% Democrats and 41% Republicans.15 The party breakdown for Member "Dear Colleague" letters is similar for the 113th Congress, with Democrats sending 73% of letters compared with 27% for Republicans. For the 113th Congress, however, the Republicans were the majority party (54% of seats) and the Democrats were the minority party (47% of seats).16

"Dear Colleague" Letter Characteristics and Purpose

"Dear Colleague" letters are often used to encourage others to cosponsor, support, or oppose a bill, resolution, or amendment. "Dear Colleague" letters concerning a bill or resolution generally include a description of the legislation along with a reason or reasons for support or opposition.17 For example, a "Dear Colleague" letter send during the 111th Congress solicited cosponsors for H.R. 483, the Victims of Crime Preservation Fund Act of 2009, and H.R. 3402, the Crime Victims Fund Preservation Act of 2009. The "Dear Colleague" letter asked for other Members to cosponsor the bill and then explained what the bills would do.

|

Dear Colleague, For 25 years, the Victims of Crime Act (VOCA) has been the lifeblood of victim service providers all over the country. Thanks to this legislation, current law now requires criminals convicted in Federal courts to pay for their crimes by paying into a court cost fund. That money is then used to help pay for grants to victim services providers, rent on the courthouse, and victims' medical or funeral expenses. This fund is money provided by criminals, and intended for victims. It is not paid for by taxpayer dollars. As cochairs of the Congressional Victims' Rights Caucus, we have introduced two bills to protect this fund and the victims it assists. H.R. 3402, Crime Victims Fund Preservation Act of 2009 will ensure a continued and substantial increase in the amount of Fund dollars that are made available to support critical crime victim services. The bill will do this by establishing minimum VOCA caps through 2014 that allow for suitable outlays while still leaving a substantial balance in the Fund for future use. H.R. 483, Victims of Crime Act Preservation Fund Act of 2009 will create a "lockbox" to ensure that this money cannot be used for anything other than victims programs. We hope you will consider cosponsoring these important bills. With this legislation, we can ensure that Congress honors the commitment that it made to victims 25 years ago.25 (emphasis in original.)18 |

Additionally, "Dear Colleague" letters are used to inform Members and their offices about events connected to congressional business, or modifications to chamber operations. The Committee on House Administration, for example, routinely circulates "Dear Colleague" letters to Members concerning matters that affect House operations, such as the announcement in the 111th Congress of support for Apple iPhones on the House network,19 or the announcement in the 113th Congress that a new Congressional Pictorial Directory was published.20

Self-Selected Categories

When a Member, officer, committee, or commission uses the e-"Dear Colleague" system to send a letter electronically, the sender may categorize the letter with up to three issue terms (see Table 3 for a list of categories). When the letter is sent, the categories are included with the "Dear Colleague" letter and are displayed in the subject line of the email sent to subscribers. In both the 111th and 113th Congresses, a majority of offices chose to assign three categories, the maximum, to their letters. Table 2 shows the number of letters that were assigned one, two, and three categories in the 111th and 113th Congresses.

|

111th Congress |

113th Congress |

|||

|

Issue Categories |

Number |

Percentage |

Number |

Percentage |

|

1 |

3,926 |

13.0% |

6,605 |

20.8% |

|

2 |

5,887 |

19.5% |

8,440 |

26.6% |

|

3 |

20,407 |

67.5% |

16,722 |

52.6% |

|

Total |

30,220 |

100.0% |

31,767 |

100.0% |

Source: CRS and Bush School of Government and Public Service compilation of data from http://e-dearcolleague.house.gov.

The available categories were created by the Committee on House Administration and the House Chief Administrative Officer based on conversations with offices that used the earlier email-based system and the categories that appeared most frequently on "Dear Colleague" letters sent through that system. The categories have not been updated or changed since they were initially approved by the Committee on House Administration in 2008.21

Table 3 shows that some categories were used more frequently by senders than others. If an office wanted to assign more than three categories to a letter, it may have sent the letter multiple times. Sending the letter multiple times with different issue terms assigned may have made it possible to reach a wider House audience. Table 3 lists the 32 available categories and the number and percentage of "Dear Colleague" letters associated with each category.

|

111th |

113th |

111th |

113th |

||||||

|

Category |

# |

% |

# |

% |

Category |

# |

% |

# |

% |

|

Health Care |

6,398 |

8.8% |

6,236 |

8.3% |

Taxes |

1,906 |

2.6% |

1,393 |

1.8% |

|

Foreign Affairs |

5,771 |

7.9% |

5,199 |

6.9% |

Homeland Security |

1,871 |

2.6% |

2,077 |

2.7% |

|

Education |

4,321 |

6.0% |

4,184 |

5.5% |

Agriculture |

1,790 |

2.5% |

2,016 |

2.7% |

|

Family Issues |

4,234 |

5.8% |

4,642 |

6.1% |

Transportation |

1,688 |

2.3% |

1,372 |

1.8% |

|

Economy |

4,037 |

5.6% |

3,150 |

4.2% |

Consumer Affairs |

1,516 |

2.1% |

1,440 |

1.9% |

|

Environment |

3,906 |

5.4% |

2,934 |

3.9% |

Technology |

1,456 |

2.0% |

1,665 |

2.2% |

|

Armed Services |

3,570 |

4.9% |

4,283 |

5.7% |

Small Business |

1,414 |

1.9% |

1,405 |

1.9% |

|

Judiciary |

3,124 |

4.3% |

4,129 |

5.5% |

Trade |

1,340 |

1.8% |

1,429 |

1.9% |

|

Appropriations |

3,098 |

4.3% |

4,288 |

5.7% |

Science |

1,331 |

1.8% |

1,770 |

2.3% |

|

Civil Rights |

2,564 |

3.5% |

3,381 |

4.5% |

Budget |

876 |

1.2% |

1,521 |

2.0% |

|

Energy |

2,496 |

3.4% |

2,178 |

2.9% |

Intelligence |

771 |

1.1% |

943 |

1.2% |

|

Labor |

2,337 |

3.2% |

2,158 |

2.9% |

Social Security |

526 |

0.7% |

610 |

0.8% |

|

Natural Resources |

2,272 |

3.1% |

2,483 |

3.3% |

Elections |

418 |

0.6% |

300 |

0.4% |

|

Government |

2,262 |

3.1% |

2,798 |

3.7% |

Rules/Legislative Branch |

374 |

0.5% |

465 |

0.6% |

|

Veterans |

2,213 |

3.0% |

2,772 |

3.7% |

Administrative |

278 |

0.4% |

272 |

0.4% |

|

Finance |

2,182 |

3.0% |

1,730 |

2.3% |

Ethics and Standards |

269 |

0.4% |

330 |

0.4% |

|

Total |

75,553 |

100.0% |

72,609 |

100.0% |

|||||

Source: CRS and Bush School of Government and Public Service compilation of data from http://e-dearcolleague.house.gov.

In both the 111th and 113th Congresses, the most popular category was healthcare (8.8% and 8.3%, respectively). This was followed by foreign affairs (7.9%; 6.9%) in both congresses. In the 111th Congress, education (6.0%) was third most popular followed by family issues (5.8%). For the 113th Congress, family issues was third most popular (6.1%), followed by education (5.5%). When evaluating the data, it is important to note that the sender selects a category. While it is possible that some of the self-assigned categories do not accurately reflect the content of the "Dear Colleague" letters, the top categories appear to mirror the House's legislative agenda in both the 111th and 113th Congresses.

Purpose of "Dear Colleague" Letters

To determine the purpose of each "Dear Colleague" letter sent during the 111th and 113th Congresses, each individual letter in the dataset was examined for content and placed into a category. For the 111th Congress, the author examined and coded each letter. For the 113th Congress, a capstone team at the Bush School of Government and Public Service at Texas A&M University examined and coded each letter. For the data from the 111th Congress, five categories were utilized:

- 1. solicited cosponsors for legislation

- 2. collected signatures for letters to executive branch officials or congressional leadership

- 3. invited other Members and staff to events

- 4. provided information or advocated on public policy, floor action, or amendments

- 5. announced administrative policies of the House

For letters from the 113th Congress, the initial five categories were expanded into seven categories by dividing the invitation and information categories to better capture the content of "Dear Colleague" letters. The use of seven categories allowed the data to be further categorized by purpose:

- 1. solicited cosponsors for legislation

- 2. collected signatures for letters to executive branch officials or congressional leadership

- 3. invited other Members or staff to receptions briefings

- 4. solicited membership for Congressional Member Organizations (i.e., caucuses)

- 5. provided general information

- 6. advocated specific floor action

- 7. announced administrative notices

Notably, the invitation category in the 111th Congress was divided to separate requests to attend a briefing from those soliciting membership in a caucus. This addition was made because of the volume of "Dear Colleague" letters that had the specific purpose of asking Members to join a caucus during the 113th Congress. Additionally, the information category was split to separate letters that were purely informational from those that advocated a specific floor action. During the 111th Congress, both types of letters were coded as informational.

For letters that expressed multiple goals, the most prominent purpose (i.e., listed in the subject line, header, or first sentence of the letter) was coded. For example, a "Dear Colleague" letter that asked for cosponsorship often also provided information on public policy or floor action. The sending office, however, by placing the word "cosponsor" in the subject line and asking other Members to contact the office to cosponsor a bill or resolution, highlighted cosponsor solicitation over other goals. Table 4 lists the purposes of letters in the 111th and 113th Congresses and the percentage of letters associated with each purpose.

|

111th Congress |

113th Congress |

||||

|

Reason for Sending |

Number |

Percentage |

Number |

Percentage |

|

|

Cosponsor |

16,850 |

53.0% |

17,002 |

42.0% |

|

|

Signatures |

6,602 |

20.8% |

10,299 |

25.4% |

|

|

Invitation |

5,810 |

18.3% |

9,510 |

23.5% |

|

|

Event, Reception, Briefing |

— |

— |

8,533 |

21.1% |

|

|

Caucus Membership |

— |

— |

977 |

2.4% |

|

|

Information |

2,114 |

6.7% |

3,010 |

7.4% |

|

|

General Information |

— |

— |

1,153 |

2.8% |

|

|

Floor Action |

— |

— |

1,857 |

4.6% |

|

|

Administrative Policy |

391 |

1.2% |

620 |

1.5% |

|

|

Other a |

— |

— |

46 |

0.1% |

|

|

Total |

31,767 |

100.0% |

40,487 |

100.0% |

|

Source: CRS and Bush School of Government and Public Service compilation of data from http://e-dearcolleague.house.gov.

Notes:

a. "Dear Colleague" letters labeled as other include letters sent without content or which were system-generated test letters.

Cosponsorship

Soliciting cosponsors for bills and resolutions was the most common reason for sending "Dear Colleague" letters in both the 111th Congress (53.0%) and the 113th Congress (42.0%). A typical letter asking for cosponsorship provides an overview of the legislation, reasons why offices should consider cosponsorship, and often lists others who have already cosponsored the letter.

Invitation to Events

"Dear Colleague" letters are frequently used to invite other Members or staff to an event, reception, or briefing. In the 111th Congress, invitation "Dear Colleague" letters accounted for 18.3% of letters sent, including invitations to join a caucus. In the 113th Congress, a total of 23.5% of "Dear Colleague" letters sent included invitations, of which 21.1% were invitations to events, receptions, or briefings and 2.4% were invitations to join a caucus. "Dear Colleague" letters inviting Members to events such as briefings and receptions are not usually associated with a particular piece of legislation. Letters inviting Members to participate in floor activities, including special order speeches, are not included in this category. They are instead included with "Floor Action" "Dear Colleague" letters.

The increase in letters that include invitations suggest that Members of Congress may have been advertising briefings and events more often in the 113th Congress than in previous congresses (even when letters that invited caucus membership were excluded). In the 111th Congress, the invitation category included requests for Members to join caucuses. For the 113th Congress, these requests were coded separately. The increase in invitation "Dear Colleague" letters could reflect an attempt by Members to provide information to colleagues through formal briefings, usually by outside organizations.

Join Caucuses

In the 113th Congress, 2.4% of "Dear Colleague" letters were sent to ask other Members to join a Congressional Member Organization (CMO or caucus). Broadly, caucuses bring together Members interested in similar policy issues or who represent interconnected constituencies and provide networking opportunities for Members with other like-minded colleagues.22 Caucus "Dear Colleague" letters typically mention the topic covered by the caucus and ask Members to join with other colleagues to promote a cause or deal with a specific policy issue.

Collect Signatures for Letters

"Dear Colleague" letters are also often used to solicit other Members to cosign letters to congressional leadership, committee chairs and executive branch officials. Past analysis of "Dear Colleague" letters found that 20.8% of letters in the 111th Congress asked other Members to sign letters.23 In the 113th Congress, the number of letters asking for signatures increased to 25.4%.

Sending letters to executive branch officials or congressional leadership can be an important tool for Members seeking to influence policymaking and gain more support or awareness for a specific topic.24 A letter to congressional leadership, committee chairs, or the executive branch with multiple signers can be used to express Members' opinion on legislation pending before the House or on executive branch policy implementation. A letter signed by multiple Members can also be used in an effort to gain leverage on a policy issue and to demonstrate broad support for a policy position.25

New to the study of "Dear Colleague" letters in the 113th Congress were a limited number of letters that asked Members to sign an Amicus Curiae brief to the Supreme Court. Amicus Curiae are used by individuals or groups who are not directly involved in a lawsuit, but have an interest in or an opinion about the matter.26 In the 111th Congress, five "Dear Colleague" letters mentioned an amicus brief, but none asked for a Member to join as a signing party. By the 113th Congress, this had changed as several "Dear Colleague" letters were sent to ask other Members to sign an amicus brief.27

Information

Members, committees, and commissions also use "Dear Colleague" letters to provide information to other Members. An informational "Dear Colleague" letter can advocate for a specific action to be taken or it can include information about an issue, sometimes accompanied by an op-ed written by the Member, or a suggested news article. In the 111th Congress, informational "Dear Colleague" letters accounted for 6.7% of letters sent. In the 113th Congress, the total number of information "Dear Colleague" letters increased to 7.4% of "Dear Colleague" letters. The total number of informational "Dear Colleague" letters, however, includes letters that advocate a specific floor action. In the 113th Congress, 4.6% of "Dear Colleague" letters advocated specific floor action and 2.8% of "Dear Colleague" letters provided general information.

Informational "Dear Colleague" letters are used for many purposes by Members, including to "signal their interest or opinion on a general topic or piece of legislation," which indicates their desire to be included in future legislation on the subject.28 The use of informational "Dear Colleague" letters could be a signal, as the literature suggests, that Members are attempting to search out other like-minded Members. It could also be an attempt for individual Members to frame the policy debate even when legislation on an issue is not scheduled for House floor action. In other words, informational "Dear Colleague" letters might be a way to engage in the policy process even when there is no pending action on a particular subject.

Floor Action

In the 113th Congress, 4.6% of letters advocated a specific action on the House floor. These "Dear Colleague" letters often ask other Members to vote for or against amendments, bills, or resolutions when a floor vote is taken.

Administrative

Officers of the House and committees use "Dear Colleague" letters to make administrative announcements. In the 111th Congress, administrative "Dear Colleague" letters accounted for 1.2% of letters in the database. In the 113th Congress, 1.5% of "Dear Colleague" letters were administrative. Administrative "Dear Colleague" letters in the 113th Congress included a Sergeant at Arms' announcement about access to House office buildings during Christmas week,29 a House Inspector General's announcement about fraud prevention week,30 and a House Chaplain's announcement for Ash Wednesday services.31 Also included are numerous announcements from the Committee on House Administration, including announcements about House policies and services.

"Dear Colleague" Letters and Legislation

As discussed above, the majority of "Dear Colleague" letters are sent to solicit cosponsors for bills and resolutions or to promote a specific floor action attached to a specific piece of legislation. Studies of how Members successfully navigate the legislative process suggest that the ability to get a bill passed is a reflection on a Member's "efficiency as a legislator."32 Subsequently, Members will often turn to "Dear Colleague" letters as a way to promote ideas internally and to gather support for legislation, or as a way to signal to the House leadership and other Members interest in a particular idea or measure.33

While research has shown that the number of cosponsors for a given bill or resolution does not generally impact its passage,34 the ability to attract cosponsors might do more than signal potential support for a specific measure or a more general alteration of public policy on a particular issue. Additionally, at least one congressional committee has used the number of cosponsors as a prerequisite for committee consideration of a measure. For example, in the 113th Congress, the House Committee on Financial Services adopted a committee rule to prohibit the scheduling of a hearing on commemorative coin legislation unless two-thirds of House Members had cosponsored the measure.35 The use of "Dear Colleague" letters is one way in which Members may recruit colleagues to cosponsor a measure and provide evidence to committees that sufficient support exists for the consideration of a bill or resolution.

The electronic "Dear Colleague" distribution system provides Members with the option of linking a "Dear Colleague" letter to a specific bill or resolution. Approximately 59.3% of "Dear Colleague" letters in the 111th Congress linked to a specific bill or resolution. In the 113th Congress, the number of linked "Dear Colleague" letters declined to 31%. Table 5 shows the percentage of legislation that was linked to "Dear Colleague" letters by measure type. Additionally, Table 5 provides a breakdown of total legislation introduced in the 111th and 113th Congresses for comparative purposes.

Table 5. "Dear Colleague" Letters Linked to Legislation and Legislation Introduced in the 111th and 113th Congresses

|

111th Congress |

113th Congress |

|||

|

Legislation Type |

"Dear Colleague" Letters Linked to Legislation |

Legislation Introduced |

"Dear Colleague" Letters Linked to Legislation |

Legislation Introduced |

|

House Bills (H.R.) |

78.1% |

74.7% |

89.9% |

85.0% |

|

House Resolution (H.Res.) |

17.6% |

20.3% |

7.8% |

11.3% |

|

House Concurrent Resolution (H.Con.Res) |

3.9% |

3.8% |

1.4% |

1.8% |

|

House Joint Resolution (H.J.Res.) |

0.4% |

1.2% |

0.9% |

1.9% |

|

Total |

100.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

Source: CRS and Bush School compilation of data from http://e-dearcolleague.house.gov; "Interim Resume of Congressional Activities: 1st Session, 111th Congress," Congressional Record, vol. 156 (January 5, 2010), p. D3; "Interim Resume of Congressional Activities: 2nd Session, 111th Congress," Congressional Record, vol. 156 (December 29, 2010), p. D1249; "Resume of Congressional Activity: 1st session, 113th Congress," Congressional Record, daily digest vol. 160 (February 27, 2014), p. D195; and "Resume of Congressional Activities: 2nd session, 113th Congress," Congressional Record, vol. 161 (March 4, 2015), p. D224.

Notes: Senate-initiated legislation (i.e., Senate bills, Senate joint resolutions, and Senate concurrent resolutions) is not included in the analysis because House Members do not have the opportunity to cosponsor these bills and resolutions.

Overall, the percentage of "Dear Colleague" letters linked to legislation declined from the 111th Congress to the 113th Congress. This was also true within each type of legislation, with the exception of House bills (H.R.), which saw an increase in the percentage of "Dear Colleague" letters linked with bills rise from 78.1% in the 111th Congress to 89.9% in the 113th Congress. Even though the number of "Dear Colleague" letters linked with non-House bills declined, the percentage of linked "Dear Colleague" letters by type of legislation continued to mirror the overall introduction of legislation by type. This included a rise in the number of House bills introduced in the 113th Congress and a corresponding rise in the number of "Dear Colleague" letters sent that linked to House bills.

Questions for Congress

Since the adoption and implementation of the e-"Dear Colleague" system in August 2008, the number of "Dear Colleague" letters sent in the House has continued to increase. In light of the analysis of the volume, use, characteristics, and purpose of "Dear Colleague" letters, several possible administrative and operations questions could be raised to aid the House in future discussions of the e-"Dear Colleague" system.

Volume Questions

As the e-"Dear Colleague" system continues to process and archive a higher volume of letters on an annual basis, consideration of the capacity of the system to deliver and archive "Dear Colleague" letters may be useful. Can the current software or infrastructure handle a continuing increase in the number of "Dear Colleague" letters? Can the current system handle the indefinite archiving of "Dear Colleague" letters? The ability for Members, committees, officers, and congressional commissions to access historic "Dear Colleague" letters is a significant addition to the e-"Dear Colleague" system. Ensuring that this form of internal communication continues to be available would provide a new dimension to Member and staff ability to understand past legislative and administrative actions.

Additionally, as the number of "Dear Colleague" letters increases, how Member and committee offices handle the receipt of letters could be important. Under the current system, individual staff can receive (by subscription) "Dear Colleague" letters of interest to them. As the number of letters increase and the number of letters with cross-listed categories grows, individual subscribers could begin receiving a single letter multiple times or could miss letters that touch on a topic that is not tagged in a particular category by the sender. Creating a process at the system level to help subscribers manage letters might alleviate problems associated with receiving multiple copies of a single letter or not receiving letters that might be of interest to an office.

Characteristics and Purpose

Examining the characteristics and purpose of "Dear Colleague" letters in the House raises several questions about additions to the current system that might aid subscribers. First, the addition of information on a letter's purpose could refine the targeting of letters to the correct audience. For example, if a letter was sent to generate bill or resolution cosponsors, labeling the letter as such would allow subscribers to immediately identify the letter's purpose. Such a label has the potential to ensure that other Members see the request for cosponsorship and the overall topic of the letter in an expedited manner.

Second, creating a linkage between "Dear Colleague" letters discussing pending legislation and Congress.gov might be useful for Member and committee offices. Such a linkage would allow Members and committees to identify "Dear Colleague" letters associated with specific legislation without searching the e-"Dear Colleague" website. Listing relevant "Dear Colleague" letters on Congress.gov could also improve the visibility of letters and attract additional interest from individuals who had not received the letter through their subscriptions.

Third, creating additional issue terms could help "Dear Colleague" letter senders better target their letters. Having additional issue term choices would allow interested subscribers to more narrowly refine the types of letters they receive, thus diminishing the overall number of potentially superfluous letters they receive. Creating additional issue terms, however, could also result in an additional influx of letters for subscribers. So long as a limit of three issue terms is placed on each letter, when a sender wants to tag a letter with more than three issue terms the letter must be sent multiple times. Adding additional issue terms may increase the number of cross-posted letters, creating additional work for subscribers to sort through the "Dear Colleague" correspondence.

Finally, since cosponsorship continues to be the most popular reason why "Dear Colleague" letters are sent, an automated way of handling responses to cosponsorship requests might be useful. Under the current e-"Dear Colleague" system, individual offices are responsible for fielding and processing requests for cosponsorship. If a new feature could be developed to compile positive responses for cosponsors, Member offices could be relieved of compiling cosponsorship lists.

Archiving Questions

"Dear Colleague" letters sent by individual House Members and committees represent the vast majority of all letters sent. A smaller percentage of letters, however, is sent by the Committee on House Administration and by House officers announcing numerous administrative and operational provisions and actions. These "Dear Colleague" letters, especially those that announce changes in administrative or operational policies, are important for the historical record of House operations. As it currently stands, the e-"Dear Colleague" system is searchable by sender, letter title, and self-selected issue category. One issue category is for administrative matters. As the e-"Dear Colleague" system matures, it could be useful to the House to ensure that administrative letters be archived to allow easy access to statements of policy implementation or enforcement announced by the House. For example, in the 113th Congress, the Committee on House Administration sent out a "Dear Colleague" letter to remind offices that a new policy was in place that required franked mailing labels are used for large items or boxes and that taped franks would no longer be accepted.36 This change to the franking regulations might be important for future Congresses to ensure that they comply with new Postal Service regulations.37

Status Quo

The House might determine that the current e-"Dear Colleague" system is effective in distributing and archiving "Dear Colleague" letters. Instead of altering how the e-"Dear Colleague" system tags, archives, or sends letters, the House could continue to use the current system to distribute and archive letters. Changes to the e-"Dear Colleague" system could then be made if necessary to strengthen the back-end computer infrastructure or make adjustments to the user interface.

Concluding Observations

The sending of electronic "Dear Colleague" letters continues to increase. In 2003, 5,161 "Dear Colleague" letters were sent by email. By 2014, 40,847 letters were sent through the web-based e-"Dear Colleague" system. This report analyzed the number of "Dear Colleague" letters sent and showed that, overall, the volume of letters sent continues to rise. This report also showed that the volume of letters closely follows the congressional calendar, with more letters sent during the first session of a Congress than during the second session. Additionally, the average number of "Dear Colleague" letters sent in the second session generally declines between September and December, which coincides with a decline in overall legislative activity at the end of a Congress.

As this report showed, more "Dear Colleague" letters were sent to solicit cosponsors (53.0% in the 111th Congress and 42.0% in the 113th Congress) than for any other purpose. While the percentage of letters asking for cosponsors has declined between the 111th and 113th Congresses, Members still frequently asked their colleagues to join them in support of legislative ideas. Also of note, the number of "Dear Colleague" letters sent to form social networks within the House (e.g., caucuses) or to influence others to take a specific action has increased. During the 111th Congress, invitation and information "Dear Colleague" letters accounted for 25.0% of all letters sent. In the 113th Congress, those letters accounted for 30.9% of all letters sent.

Cosponsorship continues to be the overriding reason to send "Dear Colleague" letters in the House. While past studies have shown that the number of cosponsorships does not influence whether legislation passes the House or is signed into law,38 cosponsorships can be an important signaling mechanism to show support for legislative ideas. Members often use "Dear Colleague" letters as a way to gauge support for specific ideas and to explore which other members might be interested in a general policy area. While party, committee service, and caucus membership might aid Members in discovering who else could be interested in a given policy area,39 response to cosponsorship requests, and the willingness of other Members to be formally listed as supporting a measure, provides a more formal signal of support for legislative ideas. The demographics of those providing formal support could contribute to whether or not a specific measure is chosen over others to move through the legislative process or whether those Members might be engaged to draft a legislative solution to a policy problem.40

Sending "Dear Colleague" letters can also be used to expand social networks and supplying information to colleagues. Past studies of social networks within Congress have found that Members are more likely to form networks with other like-minded members.41 While cosponsorship might be a tool to solidify social networks and interpersonal relationships,42 "Dear Colleague" letters allow both for the solidification of relationships between copartisans and the ability to reach out to opposite party Members for potential support.43 The ability to share information and recruit other Members for partisan and bipartisan caucuses can strengthen the informational position of the sender within the chamber and demonstrate that their office is a leader on particular policy issues.