Overview

The Pacific Islands region, also known as the South Pacific or Southwest Pacific, presents

Congress with a diverse array of policy issues. It is a strategically important region that encompasses U.S. Pacific territories.1 U.S. relations with Australia and New Zealand include pursuing common interests in the Southwest Pacific, which also has attracted Chinese diplomatic attention and economic engagement. Congress plays key roles in approving and overseeing the administration of the Compacts of Free Association that govern U.S. relations with the Marshall Islands, Micronesia, and Palau (also referred to as the Freely Associated States or FAS). The United States has economic interests in the region, particularly fishing. The United States provides foreign assistance to Pacific Island countries, which are among those most affected by climate change, particularly in the areas of climate change adaptation and mitigation.

|

Melanesian Region |

Micronesian Region |

Polynesian Region |

|

Fiji |

Kiribati |

Cook Islands (in free association with New Zealand) |

|

Papua New Guinea |

Marshall Islands (in free association with the United States) |

Niue (in free association with New Zealand) |

|

Solomon Islands |

Federated States of Micronesia (in free association with the United States) |

Samoa |

|

Vanuatu |

Nauru |

Tonga |

|

Palau (in free association with the United States) |

Tuvalu |

Notes: The Pacific Islands Forum, the main regional organization, includes the 14 states in this table, plus Australia and New Zealand, and 2 territories of France (French Polynesia and New Caledonia).

The Southwest Pacific covers 20 million square miles of ocean and 117,000 square miles of land area (roughly the size of Cuba).2 The region includes 14 sovereign states with approximately 9 million people, including three countries in "free association" with the United States—the Marshall Islands, Micronesia, and Palau. Papua New Guinea (PNG), the largest country in the Southwest Pacific, constitutes 80% of region's land area and 75% of its population. (See Table 1.) The region's gross domestic product (GDP) totals around $32 billion (about the size of Albania's GDP). Per capita incomes range from lower middle income (Solomon Islands at $2,000 per capita GDP) to upper middle income (Nauru and Palau at $14,200).3

According to many analysts, since gaining independence during the post-World War II era, many Pacific Island countries have experienced greater political than economic success. Despite weak political institutions and occasional civil unrest, human rights generally are respected and international observers largely have regarded governmental elections as free and fair. Of 12 Pacific Island states ranked by Freedom House for political rights and civil liberties, eight are given "free" status, while Fiji, Papua New Guinea, and the Solomon Islands—the three largest countries in the region—are ranked as "partly free."4

Most Pacific Island countries, with some exceptions such as Fiji, Papua New Guinea, and the Solomon Islands, have limited natural and human resources upon which to launch sustained development. Many small atoll countries in the region are hindered by lack of resources, skilled labor, and economies of scale; inadequate infrastructure; poor government services; and remoteness from international markets. In addition, some areas also are threatened by frequent weather-related natural disasters and rising sea levels related to climate change.

Regional Organizations

The Pacific Islands Forum (PIF), which was known as the South Pacific Forum until 1999, seeks to foster cooperation between member states. It is comprised of 18 states and territories. The PIF's 16 states are Australia, Cook Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia, Fiji, Kiribati, Nauru, New Zealand, Niue, Palau, Papua New Guinea, the Republic of the Marshall Islands, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tonga, Tuvalu, and Vanuatu. Its two territories are French Polynesia and New Caledonia. The PIF Secretariat is located in Suva, Fiji. Key issues addressed by the PIF include climate change, regional security, and fisheries. American Samoa, Guam, and the Northern Marianas have observer status with the PIF.

The Melanesian Spearhead Group (MSG), founded in 1986, includes the following Melanesian countries and organizations: Fiji, the Kanak Socialist Liberation Front (FLNKS) of New Caledonia, Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, and Vanuatu. The MSG seeks to have "common positions and solidarity in spearheading regional issues of common interest, including the FLNKS cause for political independence in New Caledonia."5 In 2015, the MSG granted the United Liberation Movement for West Papua observer status and Indonesia associate member status.6

The Pacific Islands and U.S. Interests

On the whole, the United States enjoys friendly relations with Pacific Island countries and has benefitted from their support in the United Nations. This is especially true of the Freely Associated States, particularly Palau, which in 2014 reportedly voted with the United States 90% of the time.7 (See "Compacts of Free Association" below.) The United States has worked with Australia, the preeminent power in the Southwest Pacific, to help advance shared strategic interests, maintain regional stability, and promote economic development, particularly since the end of the Cold War in the early 1990s. New Zealand also has cooperated with U.S. initiatives in the region, been a major provider of foreign aid, and helped lead peacekeeping efforts. France and Japan also maintain significant interests in the region. China has become a diplomatic force, major source of foreign aid, and leading trade partner in the Southwest Pacific. In addition, more recently, other nations, including Russia, India, and Indonesia, have made efforts to expand their engagement in the region.

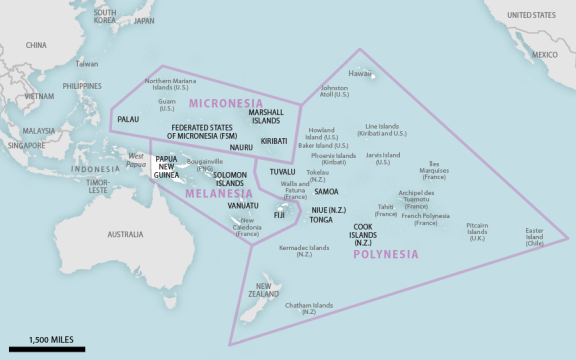

The Pacific Islands generally can be divided according to four spheres of influence, those of the United States, Australia, New Zealand, and France. The American sphere extends through parts of the Micronesian and Polynesian subregions. (See Figure 1.) In the Micronesian region lie the U.S. territories Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands as well as the Freely Associated States. In the Polynesian region lie Hawaii and American Samoa. U.S. security interests in the Micronesian subregion, including military bases on Guam and Kwajalein Atoll in the Marshall Islands, constitute what some experts call a defensive line or "second island chain" in the Pacific.8 The first island chain includes southern Japan, Taiwan, and the Philippines. Some analysts in China have viewed the island chains as serving to contain China and the Chinese navy.9 The region also was a key strategic battleground during World War II, where the United States and its allies fought against Japan.

Australia's interests focus on the islands south of the equator, particularly the relatively large Melanesian nations of Papua New Guinea, which Australia administered until PNG gained its independence in 1975, the Solomon Islands, and Vanuatu. New Zealand has long-standing ties with its territory of Tokelau, former colony of Samoa (also known as Western Samoa), and the Cook Islands and Niue, two self-governing states in "free association" with New Zealand. Australia and New Zealand often cooperate on regional security matters such as peacekeeping. France continues to administer French Polynesia, New Caledonia, and Wallis and Futuna.

U.S. policymakers have emphasized the importance of the Pacific Islands region for U.S. strategic and security interests. In testimony before the Subcommittee on Asia and the Pacific of the House Committee on Foreign Affairs, former Deputy Assistant Secretary of State Matthew Matthews emphasized the changing strategic context of the Pacific Islands region:

The Pacific Island region has been free of great power conflict since the end of World War II, we have enjoyed friendly relations with all of the Pacific island countries. This state of affairs, however, is not guaranteed.... Our relations with our Pacific partners are unfolding against the backdrop of shifting strategic environment, where emerging powers in Asia and elsewhere seek to exert a greater influence in the Pacific region, through development and economic aid, people-to-people contacts and security cooperation. There is continued uncertainty in the region about the United States' ... willingness and ability to sustain a robust forward presence.10

During the hearing, then-Chairman of the Subcommittee on Asia and the Pacific former Representative Matt Salmon stated that the countries of the region deserve U.S. attention "for the important roles that they play in regional security, as participants in international organizations, and as the neighbors to our own U.S. territories of American Samoa, Guam and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands."11

Some analysts have expressed concerns about the long-term strategic implications of China's growing engagement in the region. Other experts have argued that China's diplomatic outreach and economic influence have not translated into significantly greater political sway over South Pacific countries, and that Australia, a U.S. ally, remains the dominant power and provider of development assistance in the region.12 Some observers also have contended that Chinese military assistance and cooperation in the region remain modest compared to that of Australia, and that China has not actively sought to project "hard power."13

U.S. Policies in the South Pacific

Broad U.S. objectives and policies in the region have included promoting sustainable economic development and good governance, addressing the effects of climate change, administering the Compacts of Free Association, supporting regional organizations, projecting a presence in the region, and cooperating with Australia and regional aid donors. Other areas of concern and cooperation include combating illegal fishing, supporting peacekeeping operations, and responding to natural disasters.

Areas of particular concern to Congress include overseeing U.S. policies in the Southwest Pacific and the administration of the Compacts of Free Association; regional foreign aid programs and appropriations; approving the U.S.-Palau agreement to provide U.S. economic assistance through 2024; and supporting the U.S. tuna fleet. The Obama Administration asserted that as part of its "rebalancing" to the Asia-Pacific region, it had increased its level of engagement in the Southwest Pacific, including expanding staffing and programming and increasing the frequency of high-level meetings with Pacific leaders.14 Other observers contended that the rebalancing policy had not included a corresponding change in the level of attention paid to the Pacific Islands region.15

U.S. diplomatic outreach to the region includes the following:

- In 2011, then-President Obama met with Pacific Island leaders on the margins of the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Leaders Meeting.

- In 2012, Hillary Clinton attended the Pacific Islands Forum annual summit, the first Secretary of State to do so, in the Cook Islands, where she noted U.S. assistance to the region and highlighted three U.S. objectives: trade, investment in energy, and sustainable growth; peace and security; and women's empowerment.16

- In 2013, then-Secretary of State John Kerry met with Pacific Island leaders at the United Nations and pledged to work with the region to address climate change.

- In 2014, then-Secretary Kerry visited the Solomon Islands following devastating floods there.17

- In 2015, then-President Obama met with leaders of Kiribati, the Marshall Islands, and Papua New Guinea at the Paris Climate Conference.

- In September 2016, then-Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs Daniel Russel led a U.S. delegation to the 28th Pacific Islands Forum in Pohnpei, Micronesia. Main topics of discussion included climate change, management and conservation of fisheries and other marine resources, sustainable development, regional economic integration, and human rights in West Papua.18

Foreign Assistance

|

MCC Compact with Vanuatu The Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC), an independent U.S. foreign aid agency established in 2004, awards aid packages to countries that have demonstrated good governance, investments in health and education, and a commitment to economic freedom. The 5-year MCC compact with Vanuatu (2006-2011) funded 11 public works projects worth $65 million, including roads, an air strip, wharves, and storage warehouses. |

The region depends heavily upon foreign aid. In terms of official development assistance (ODA) as defined by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), which focuses on grant-based assistance, OECD members Australia, New Zealand, the United States, France, and Japan are the principal aid donors in the Southwest Pacific. Major multilateral sources of ODA include the World Bank's International Development Association and the Asian Development Bank. According to the OECD, in 2014, the most recent year for which full data are available, the leading aid donors committed ODA to the region as follows: Australia, $850 million; New Zealand, $374 million; the United States, $277 million; France, $126 million; and Japan, $107 million.19 Although the United States remains one of the largest providers of ODA to the region by some measures, U.S. assistance remains concentrated among the Freely Associated States. China has become a major source of foreign assistance, but Chinese aid differs from traditional ODA due to its heavy emphasis on concessional loans and infrastructure projects (see "China's Foreign Assistance and Trade" below).

The U.S. government administers foreign assistance to Pacific Island countries through the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) Office for the Pacific Islands (based in the Philippines) and Pacific Islands Satellite Office (based in Papua New Guinea). U.S. foreign assistance activities include regional environmental programs; military training; disaster assistance and preparedness; fisheries management; HIV/AIDS prevention, care, and treatment programs in Papua New Guinea; and strengthening democratic institutions in Papua New Guinea, Fiji, and elsewhere.20 U.S. assistance also aims to help strengthen Pacific Islands regional fora.21

USAID has partnered with Pacific Islands regional organizations to carry out a five-year program to coordinate responses to the adverse impacts of climate change.22 Through the Coastal Community Adaptation Program, USAID supports local-level climate change interventions in nine Pacific Island countries.23 The United States supports natural disaster mitigation and response capabilities and weather and climate change adaptation programs in the Marshall Islands and Micronesia, two low-lying atoll nations, and elsewhere in the Pacific Islands region. USAID's Regional Development Mission-Asia (RDM/A) carries out several environmental programs in the region, particularly in Papua New Guinea.

Table 2. Selected U.S. Foreign Operations, Compact of Free Association, and Other Assistance to the Pacific Islands, FY2016 (estimated)

(in millions of dollars)

|

Account |

DA |

ESF |

GHP |

IMET |

Compact |

Total |

|

Fiji |

0.200 |

0.200 |

||||

|

Marshall Islands |

0.500 |

109.000 |

109.500 |

|||

|

Micronesia |

0.500 |

75.000 |

75.500 |

|||

|

Palau |

13.000 |

13.000 |

||||

|

Papua New Guinea |

1.500 |

4.500 |

0.250 |

6.25.0 |

||

|

Samoa |

0.100 |

0.100 |

||||

|

Tonga |

0.250 |

0.250 |

||||

|

Regional |

9.500 |

9.500 |

||||

|

RDM/A |

0.436 |

0.436 |

||||

|

SPTT |

21.000 |

21.000 |

||||

|

Total |

12.436 |

21.000 |

4.500 |

0.800 |

197.000 |

235.736 |

Source: U.S. Department of State, Congressional Budget Justification, Foreign Operations, FY2017; U.S. Department of the Interior, Office of Insular Affairs, FY2017 Budget Justification; USAID, Foreign Aid Explorer.

Notes: Compact—Compact of Free Association direct economic assistance; DA—Development Assistance; ESF—Economic Support Fund; GHP—Global Health Programs; IMET—International Military Education and Training; RDM/A—Regional Development Mission-Asia; SPTT—South Pacific Tuna Treaty. The amounts in this table do not include disaster assistance.

The United States conducts International Military Education and Training (IMET) programs related to peacekeeping operations, strengthening national security, responding to natural and man-made crises, developing democratic civil-military relationships, and building military and police professionalism in Fiji, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, and Tonga.24 The Obama Administration requested $1 million in Foreign Military Financing (FMF) for FY2016 for a regional program to promote peacekeeping activities, English language capabilities, and professionalism in the military. (See Table 2.) For FY2017, U.S. assistance aims to expand engagement with the PIF and other regional bodies to improve democratic development and governance in the region.25

South Pacific Tuna Treaty

Funding provided pursuant to the South Pacific Tuna Treaty (SPTT) constitutes a major source of U.S. assistance to some Pacific Island countries.26 Under the SPTT, in force since 1988, Pacific Island parties to the treaty provide access for U.S. tuna fishing vessels to fishing zones in the Southwest Pacific, which supplies one-third of the world's tuna. In exchange, the American Tunaboat Association pays licensing fees to Pacific Island parties to the treaty. In addition, as part of the agreement, the United States provides economic assistance to the Pacific Island parties totaling $21 million per year. In January 2016, the United States temporarily withdrew from the agreement, arguing that the terms were "no longer viable" for the U.S. tuna fleet. The U.S. fleet argued that it could no longer pay quarterly fees due to sharply declining prices for tuna and competition from other countries, some of which was illegal. U.S. boats resumed fishing in the region in March 2016 but with fewer fishing days allotted than in 2015.27 Talks to renegotiate the SPTT resulted in an agreement in principle in June 2016 that aims to "establish more flexible procedures for commercial cooperation between Pacific Island Parties and US industry."28

Compacts of Free Association

Congress plays roles in approving and overseeing the administration of the Compacts of Free Association that govern U.S. diplomatic, economic, and military relations with the Marshall Islands, Micronesia, and Palau. U.S. economic commitments to the Freely Associated States—totaling nearly $200 million in FY201529—are administered by the Department of the Interior. The Compact of Free Association Review Agreement, signed by the United States and the Republic of Palau in 2010, awaits congressional approval. Since 2000, the Republic of the Marshall Islands has unsuccessfully sought additional compensation for damages related to U.S. nuclear testing on Marshall Islands atolls during the 1940s and 1950s.

Background

In 1947, the Marshall Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia, Palau, and the Northern Marianas, which had been under Japanese control during part of World War II, became part of the U.S.-administered United Nations Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands. In the early 1980s, the Marshall Islands and Micronesia rejected the option of U.S. territorial or commonwealth status and instead chose free association with the United States. Compacts of Free Association were negotiated and agreed by the governments of the United States, the Marshall Islands, and Micronesia, and approved by plebiscites in the Trust Territory districts and by the U.S. Congress in 1985 (P.L. 99-239). Congress approved the Compact with Palau in 1986 (P.L. 99-658), which Palau ratified in 1994. The Compacts were intended to establish democratic self-government and to advance economic development and self-sufficiency through U.S. grant and federal program assistance, and to further the national security of the Freely Associated States (FAS) and the United States in light of Cold War geopolitical concerns.

Under the Compacts, the FAS are sovereign nations that conduct their own foreign policy, but the United States and the FAS are subject to certain limitations and obligations regarding international security and economic relations. The United States is obligated to defend the Freely Associated States against attack or threat of attack. The United States may block FAS government policies that it deems inconsistent with its duty to defend the FAS (the "defense veto"), and it has the prerogative to reject the strategic use of, or military access to, the FAS by third countries (the "right of strategic denial"). The United States also may establish military bases in the FAS, and the Marshall Islands is home to a premier U.S. military facility (the Ronald Reagan Ballistic Missile Defense Test Site [RTS], also known as the Kwajalein Missile Range). 30

The Freely Associated States and their citizens are eligible for various U.S. federal programs and services. FAS citizens are entitled to reside and work in the United States and its territories as "lawful non-immigrants" and are eligible to volunteer for service in the U.S. armed forces. Several hundred FAS citizens serve in the U.S. military and roughly 12 FAS citizens serving in the U.S. armed forces died in the Iraq and Afghanistan war efforts. The Marshall Islands, Micronesia, and Palau were members of the U.S.-led coalition that launched Operation Iraqi Freedom in 2003.31

|

Kwajalein Missile Range The United States military regularly conducts intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) testing and space surveillance activities from the Kwajalein Missile Range. Former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Martin E. Dempsey referred to the site as the "world's premier range and test site for intercontinental ballistic missiles and space operations support."32 Under the Military Use and Operating Rights Agreement (MUORA), the United States makes annual payments ($18 million) to the Marshall Islands government, which compensates Kwajalein landowners for relinquishing their property through a Land Use Agreement. The amended Compact of 2003 extended U.S. base rights at Kwajalein Atoll through 2066, with the U.S. option to continue the arrangement for an additional 20 years (to 2086). |

The FAS economies depend heavily on U.S. support. The Department of the Interior provides direct economic or grant assistance to the FAS. Its Office of Insular Affairs is responsible for administering the Compacts. The Compacts with the Marshall Islands and Micronesia provided economic assistance totaling roughly $2.5 billion between 1987 and 2003, including payments for damages and personal injuries caused by U.S. nuclear testing on Marshall Islands atolls during the 1940s and 1950s. In December 2003, the Compacts were amended in order to extend economic assistance for another 20 years and establish trust funds that aim to provide sustainable sources of government revenue after 2023. Projected U.S. grant assistance and trust fund contributions to the Marshall Islands for the 2004-2023 period total $629 million and $235 million, respectively. Projected grant assistance and trust fund contributions to Micronesia for the same period total $1.4 billion and $442 million, respectively.33

Palau: Compact of Free Association Review Agreement

In 1986, the United States and Palau signed a 50-year Compact of Free Association. The Compact was approved by the U.S. Congress but not ratified in Palau until 1993 (entering into force on October 4, 1994). The U.S.-Palau Compact provided for 15 years of direct economic assistance, the construction of a 53-mile road system, a trust fund, services of some U.S. federal agencies such as the U.S. Postal Service and the National Weather Service, and eligibility for some U.S. federal education, health, and other programs. Between 1995 and 2009, U.S. assistance totaled over $850 million, including grant assistance, road construction, and the establishment of a trust fund ($574 million), Compact federal services ($25 million), and discretionary federal program assistance ($267 million).34

|

Economic Assistance Provisions |

|

|

Trust Fund Contributions, FY2013-23 |

30.3 |

|

Infrastructure Maintenance Fund, FY2011-24 |

28.0 |

|

Fiscal Consolidation Fund, FY2011-12 |

10.0 |

|

Economic Assistance, FY2011-23 |

107.5 |

|

Infrastructure Projects, FY2011-15 |

40.0 |

|

Direct Economic Assistance Subtotal |

215.0 |

Source: Government Accountability Office, 2012.

Notes: Numbers may differ slightly from other sources due to rounding.

Under the Compact, direct economic assistance was to terminate in 2009 while annual distributions from the trust fund were to increase, to help offset the loss of economic assistance. However, Palauan leaders and some U.S. policymakers argued that continued assistance to Palau beyond 2009 was necessary. Furthermore, the value of the Compact trust fund fell from nearly $170 million to $110 million in 2008-2009 due to the global financial crisis, although it rebounded and was valued at approximately $184 million in 2015.35 In September 2010, the United States and Palau agreed to renew Compact economic assistance, but it awaits approval by Congress. (See Table 3.)

The 2010 accord provided for $215.75 million in direct economic assistance over an additional 15-year period (2011-2024).36 According to some estimates, U.S. support, including both direct economic assistance and projected discretionary program assistance, would total approximately $427 million between 2011 and 2024. In addition, the agreement committed Palau to undertake economic, legislative, financial, and management reforms.37

Although there has been bipartisan support for continued assistance, Congress has yet to approve the renewal agreement, also known as the Compact of Free Association Review Agreement, largely for budgetary reasons. From FY2010 to FY2016, the U.S. government continued annual direct economic assistance to Palau at 2009 levels ($13.1 million), pending congressional approval of the 2010 agreement and resolution of funding issues. Other U.S. assistance pursuant to the agreement, however, remained unfunded.38

During the 114th Congress, two bills were introduced in support of the agreement to extend Compact assistance to Palau. S. 2610, A Bill to Approve an Agreement Between The United States and the Republic of Palau, would not significantly alter total U.S. economic assistance to Palau from the levels specified in the 2010 renewal agreement, although the assistance would be allocated in different increments due in part to the delay in implementing the agreement. H.R. 4531, To Approve an Agreement Between the United States and the Republic of Palau, and for Other Purposes, would provide an additional $31.8 million as well as reschedule U.S. assistance.39 In addition, the conference report (H.Rept. 114-840) to accompany S. 2943, The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2017, included the following statement: "The conferees believe that enacting the Compact Review Agreement is important to United States' national security interests and, as such, believe that the President should include the Compact Review Agreement in the Fiscal Year 2018 budget request."40

Marshall Islands Nuclear Test Damages Claims

From 1946 to 1958, the United States conducted 67 atmospheric atomic and thermonuclear weapons tests on the Marshall Islands atolls of Bikini and Enewetak. In 1954, "Castle Bravo," the second test of a hydrogen bomb, was detonated over Bikini atoll, resulting in dangerous levels of radioactive fallout upon the populated atolls of Rongelap and Utrik. Between 1957 and 1980, the residents of the four northern atolls returned to their homelands (Rongelap and Utrik in 1957; Bikini in 1968; and Enewetak in 1980). However, the peoples of Bikini and Rongelap were re-evacuated to other islands in 1978 and 1985, respectively, after the levels of radiation detected in the soil were deemed unsafe for human habitation. Although diving and tourist facilities have operated on Bikini on and off since 1996, and the U.S. government had declared some parts of Rongelap safe for human habitation following a $45 million cleanup effort, neither atoll has been resettled.41 Some experts claim that remediation techniques, primarily replacing surface soil in populated areas and adding potassium chloride fertilizer to agricultural areas, has made resettlement possible, although most of the displaced people have refused to return.42

U.S. Nuclear Test Compensation

The Compact of Free Association established a Nuclear Claims Fund of $150 million and a Nuclear Claims Tribunal (NCT) to adjudicate claims. Investment returns on the Fund were expected to generate revenue for personal injury and property damages awards, health care, resettlement, trust funds for the four atolls, and quarterly distributions to the peoples of the four atolls for hardships suffered. In all, the United States reportedly has provided over $600 million for nuclear claims, health and medical programs, and environmental cleanup and monitoring.43

The Compact deems the Nuclear Claims Fund as part of a "full and final settlement" of legal claims against the U.S. government. However, the Fund was depleted by 2009 and was not sufficient to cover the NCT's awards of $96 million to approximately 2,000 individuals for compensable injuries. In addition, the Tribunal awarded, but was unable to pay, approximately $2.2 billion to the four atoll governments for remediation and restoration costs, loss of use, and consequential damages.44

Marshall Islands Legal Actions

The Marshall Islands government and peoples of the four most-affected atolls long have argued that greater U.S. compensation was justified for loss of land, personal injuries, and property damages. They have claimed that the nuclear tests caused high incidences of miscarriage, birth defects, and weakened immune systems, as well as high rates of thyroid, cervical, and breast cancer.45 In addition, some experts contend that more than a dozen Marshall Islands atolls, rather than only four, were affected.46 Some experts have disputed the Marshall Islands claims, pointing to some earlier studies.47

In September 2000, the government of the Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI) submitted to the U.S. Congress a Changed Circumstances Petition requesting additional compensation of roughly $1 billion for personal injuries, property damages, public health infrastructure, and a health care program for those exposed to radiation. The Petition based its claims upon the "changed circumstances" provision of Section 177 of the Compact, arguing that "new and additional" information, such as greater radioactive fallout than previously known or disclosed and revised radiation protection standards, constituted "changed circumstances" and that existing compensation was "manifestly inadequate." In November 2004, the George W. Bush Administration released a report evaluating the Petition, Report Evaluating the Request of the Government of the Republic of the Marshall Islands Presented to the Congress of the United States of America, concluding that there was no legal basis for considering additional compensation payments.48

In April 2006, the peoples of Bikini and Enewetak atolls filed lawsuits against the United States government in the U.S. Court of Federal Claims seeking additional compensation related to the U.S. nuclear testing program. The court dismissed both lawsuits on August 2, 2007. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit upheld the lower court ruling on January 30, 2009, finding that Section 177 of the Compact removed U.S. jurisdiction. In April 2010, the Supreme Court declined to hear the case.49

In April 2014, the RMI filed suits in the United States and the International Court of Justice in the Hague against the United States and eight other nuclear powers, claiming their failure to meet their obligations toward nuclear disarmament under Article VI of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. The lawsuits did not seek compensation but rather action on disarmament. On February 3, 2015, a federal court in California dismissed the RMI suit against the United States, on the grounds that the RMI lacked standing to bring the case and that the case was resolvable by the political branches of government rather than the courts. 50

China's Growing Influence

Some policymakers, including Members of Congress, have expressed concerns about China's growing influence in the region.51 China has become a growing political and economic actor in the Southwest Pacific, and some observers contend that it aims to promote its interests in a way that potentially displaces the influence of traditional actors in the region such as the United States, Australia, and New Zealand. In the view of one analyst, "China clearly does seek to become at least a leading power in the Western Pacific and perhaps the leading power in the Western Pacific."52 One expert reports that China's principal strategic activity in the region is signals intelligence monitoring. Toward this end, China reportedly has regularly sent vessels to the region that both track satellites and ballistic missiles and also gather intelligence.53

Other analysts argue that Beijing does not consider the South Pacific to be of key strategic importance, and note that Australian assistance remains significantly larger than that provided by Beijing.54 Some believe that although many Pacific Island leaders say they appreciate China's economic engagement and diplomatic policy of "non-interference" in domestic affairs, the region maintains strong ties to Australia and the West that are rooted in shared history and culture as well as migration.55

Beijing's engagement in the region has been motivated largely by a desire to garner support in international fora and find sources of raw materials. According to some analysts, China began to fill a vacuum created by waning U.S. attention following the end of the Cold War.56 While the United States does not maintain an embassy in several Pacific Islands countries, for example, Beijing has opened diplomatic missions in all eight of the Pacific Island countries with which it has diplomatic relations. China-Taiwan "dollar diplomacy," in which the two entities competed for official diplomatic recognition through offers of foreign aid, has been a declining factor since the late 2000s.57

|

Fiji-China Relations Some analysts view Fiji as an example of how deteriorating relations between Pacific Island countries and Western powers in the region may result in greater Chinese influence, although the significance of that influence is debated. China has become a main source of foreign aid and diplomatic support to Fiji, particularly after major foreign aid donors, including Australia, New Zealand, the EU, and the United States, imposed limited sanctions in response to the 2006 military coup.58 Major donors resumed foreign aid after Fiji held parliamentary elections in 2014, which international observers viewed as free and fair.59 During the interim period, Josaia Voreqe "Frank" Bainimarama, who has been the leader of Fiji since 2007 and was elected Prime Minister in 2014, put in place a "Look North" policy under which relations with China became more important.60 After Australia and New Zealand supported Fiji's suspension from the PIF, the Fijian government focused its attention on the Melanesian Spearhead Group. According to analysts, China seized this opportunity, sponsoring the creation of the MSG Secretariat, and building its headquarters in Vanuatu.61 Prime Minister Bainimarama has argued that Australia and New Zealand should only be allowed to remain members of the Pacific Islands Forum if China and Japan are allowed to join.62 In 2015, China and Fiji agreed to expand military cooperation.63 |

China's Foreign Assistance and Trade

China is one of the top providers of foreign assistance in the Southwest Pacific, providing $150 million in foreign assistance per year on average during the past decade. China has held two China-Pacific Island Countries Economic Development and Cooperation Forums (2006 and 2013), where Chinese officials announced large aid packages, including pledges of preferential loans ($376 million in 2006 and $1 billion in 2013). In November 2014, Chinese President Xi Jinping travelled to Fiji to establish a strategic partnership between China and eight Pacific Island countries.64 China also has provided support to the Pacific Islands Forum and has helped finance some of the organization's activities and initiatives.

Despite China's rise, Australia remains the dominant foreign aid donor in the region. Between 2006 and 2014, Australia reportedly provided approximately $7.7 billion in foreign aid to the region, compared to the United States ($1.9 billion), China ($1.8 billion), New Zealand ($1.3 billion), Japan ($1.2 billion), and France ($1.0 billion).65 In terms of grant-based aid, China's foreign assistance is relatively small. Unlike other major donors, which provide mostly grant assistance, nearly 80% of Chinese aid reportedly has been provided in the form of preferential loans, generally to finance infrastructure projects that use Chinese companies and labor.66

Table 4. Pacific Island Trade with the China, Australia, and the United States, 2015

(in millions of dollars)

|

China |

Australia |

United States |

||||

|

Cook Islands |

|

|

|

|||

|

Micronesia |

|

|

|

|||

|

Fiji |

|

|

|

|||

|

Kiribati |

|

|

|

|||

|

Nauru |

|

|

|

|||

|

Niue |

|

|

|

|||

|

Palau |

|

|

|

|||

|

Papua New Guinea |

|

|

|

|||

|

Marshall Islands |

|

|

|

|||

|

Samoa |

|

|

|

|||

|

Solomon Islands |

|

|

|

|||

|

Tonga |

|

|

|

|||

|

Tuvalu |

|

|

|

|||

|

Vanuatu |

|

|

|

|||

|

Totals |

|

|

|

Source: Global Trade Atlas

China's foreign assistance to the Southwest Pacific, like its economic assistance to many other regions, largely consists of concessional loans, infrastructure and public works projects, and investments in the extraction of natural resources. Papua New Guinea is the largest Pacific recipient of Chinese aid, having received 35% of Chinese assistance to the region. Other major recipients include Fiji, Vanuatu, and Samoa. China's foreign assistance has resulted in 218 projects since 2006, including Chinese-built roads, sea ports, airports, hydropower facilities, mining operations, hospitals, government buildings, educational facilities, sports stadiums, and other public works. Other Chinese assistance areas include public health, education, fisheries conservation, the environment, and financial support for Fiji's elections in 2014.67 Recent, smaller forms of aid reportedly include rowing machines for Samoa, water supply systems for small towns in Tonga, and quad bikes for Cook Islands legislators. Beijing also reportedly has provided modest military equipment and training to Fiji, Papua New Guinea, and Tonga.68

Some observers have criticized Chinese assistance, arguing that some infrastructure projects are poor in quality and that some Chinese loans and aid activities lack transparency and exacerbate corruption, increase debt burdens, or harm the environment. Other concerns are that some Chinese economic projects and investments do not employ local labor or that they are not directly aimed at reducing poverty.69 Some experts contend that Chinese aid has reduced the regional influence of Australia, the United States, and European countries, while others dispute this contention. Another issue is the relatively recent influx of Chinese traders and shop owners in some urban areas, which reportedly has caused resentment among some native residents. 70

China is a major trading partner in the region, surpassing even Australia, and has economic interests in the following sectors: energy production (hydro power and gas), mining, fisheries, timber, agriculture, and tourism. (See Table 3.) The largest Chinese investment project is the $1.6 billion Ramu Nickel mine in Papua New Guinea. China also has become a major source of tourists and is the only non-Pacific Island nation to be a member of the South Pacific Tourism Organization.

Australia, New Zealand, and Other External Actors

The United States has relied upon Australia, and to a lesser extent New Zealand, to help advance shared strategic interests, maintain regional stability, and promote economic development in the Southwest Pacific. Australia has played a critical role in helping to promote security in places such as Timor-Leste, which gained its independence from Indonesia following a 1999 referendum that turned violent, the Solomon Islands, and Bougainville, which is part of Papua New Guinea.71 The 2016 Australia Defence White Paper articulates Australia's approach to the South Pacific:

The South Pacific region will face challenges from slow economic growth, social and governance challenges, population growth and climate change. Instability in our immediate region could have strategic consequences for Australia should it lead to increasing influence by actors from outside the region with interests inimical to ours. It is crucial that Australia help support the development of national resilience in the region to reduce the likelihood of instability. This assistance includes defence cooperation, aid, policing and building regional organisations.... We will also continue to take a leading role in providing humanitarian and security assistance where required.72

New Zealand's Pacific identity, derived from its geography and growing population of New Zealanders with Polynesian or other Pacific Island ethnic backgrounds, as well as its historical relationship with the South Pacific, undergirds its relationship with the region.73 The June 2016 New Zealand Defence White Paper articulates New Zealand's ongoing interest in the South Pacific:

Given its strong connections with South Pacific countries, New Zealand has an enduring interest in regional stability. The South Pacific has remained relatively stable since 2010, and is unlikely to face an external military threat in the foreseeable future. However, the region continues to face a range of economic, governance, and environmental challenges. These challenges indicate that it is likely that the Defence Force will have to deploy to the region over the next ten years, for a response beyond humanitarian assistance and disaster relief. New Zealand will continue to protect and advance its interests by maintaining strong international relationships, with Australia in particular, and with its South Pacific partners, with whom it maintains a range of important constitutional and historical links.74

New Zealand works closely with Pacific Island states on a bilateral and multilateral basis. It has played a key role in promoting peace and stability in the Southwest Pacific in places such as Timor-Leste, the Solomon Islands, and Bougainville, and Papua New Guinea. Approximately 60% of New Zealand's foreign assistance goes to the Southwest Pacific.75 In September 2015, Wellington pledged to increase foreign assistance to the region by $100 million to reach a total of $1 billion in expenditures over the next three years.76 New Zealand also has provided development and disaster assistance to the region. In 2015, New Zealand's then-Prime Minister John Key reaffirmed New Zealand's support for the Pacific Islands Forum and sustainable South Pacific economic development, including for sustainable fisheries.77 An estimated $2 billion worth of fish is taken legally from the waters of the 14 PIF countries, with an additional $400 million worth of fish thought to be taken illegally each year.78

France

France's decision to stop nuclear testing in the South Pacific in 1996 opened the way for improved relations with the region. Although much of France's regional military presence was withdrawn following its decision to stop nuclear testing, France continues to have a military presence that reportedly includes 2,800 personnel and 7 ships, including surveillance frigates and patrol vessels.79 France is also a member of the Quadrilateral Defense Coordination Group, along with the United States, Australia, and New Zealand, which seeks to coordinate maritime security in the South Pacific. France recently signed a $39 billion deal to provide 12 new submarines to the Australian Navy.80

Other External Actors

Other external actors are becoming more active in the Southwest Pacific.81 Russia reportedly has sent a shipment of weapons with advisors to help train the Fijian military in the use of recently delivered equipment.82 India reportedly is exploring the possibility of establishing a satellite monitoring station in Fiji.83

Indonesia, too, has become more interested in the region, often with regards to its relations with the Melanesian countries. Indonesia has been a dialogue partner of the Pacific Islands Forum since 2001. Indonesian objectives related to the PIF include repositioning Indonesia's foreign policy towards a "look east policy" and getting "closer to the countries of the Pacific region," maintaining "the integrity of the unitary Republic of Indonesia," and improving the "image of Indonesia."84 The PIF and Melanesian countries have criticized human rights abuses in West Papua, Indonesia, which has a large, ethnically Melanesian indigenous population.85 Alleged human rights violations include the harassment of human rights groups and arbitrary arrests of independence activists.86 Some Melanesian countries have supported self-determination for West Papua and its inclusion in the Melanesian Spearhead Group.87 Indonesia has responded that it is a democratic country that is committed to human rights. It has resisted "interference in its domestic affairs" and in 2015 refused to accept a PIF fact-finding mission to investigate human rights violations.88

Climate Change and Other Environmental Issues

Pacific Island countries have sought international support for helping them to cope with the impacts of climate change, reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, and increase renewable energy use and energy efficiency. U.S. assistance efforts in the region have focused on climate change adaptation and strengthening governmental capacity to attract international financing and successfully implement environmental programs.89 Many experts view the Pacific Islands as highly vulnerable to the effects of climate change and other environmental problems, such as sea level rise, ocean acidification, invasive species, and extreme weather events. These environmental issues can have adverse effects on agriculture, drinking water supplies, fisheries, and tourism.

A report by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service states

Climate change presents Pacific Islands with unique challenges including rising temperatures, sea-level rise, contamination of freshwater resources with saltwater, coastal erosion, an increase in extreme weather events, coral reef bleaching, and ocean acidification. Projections for the rest of this century suggest continued increases in air and ocean surface temperatures in the Pacific, increased frequency of extreme weather events, and increased rainfall during the summer months and a decrease in rainfall during the winter months.90

Some areas of the region lie only 15 feet above sea level, and if sea levels continue to rise as projected, Kiribati, Tokelau, and Tuvalu may be uninhabitable by 2050.91 Some experts predict that many Pacific Islanders face displacement over the coming decades. Kiribati reportedly is buying land in Fiji in case its population needs to relocate.92

Much of the Republic of the Marshall Islands is less than six feet above the sea, and some experts say that rising sea levels may make many areas of the country unfit for human habitation in the coming decades.93 Bikini Islanders, with the support of the U.S. Department of the Interior, have asked to be allowed to resettle in the United States. They claim that Kili and Ejit, the islands to which Bikini Islanders were relocated before and after the nuclear tests of the 1940s and 1950s and where about 1,000 of them currently live, can no longer sustain them, due to a lack of resources and a greater frequency of bad weather. Recurrent flooding from storms and high tides has disrupted water supplies and destroyed crops. The Department of the Interior has proposed that the U.S. resettlement fund set up for Bikini Islanders help to support their relocation to the United States.94

The Paris Agreement and the Pacific

Pacific Island states were very active in seeking to influence the outcome of the U.N. Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP) in Paris, France, in 2015. The Paris Agreement includes several outcomes sought by Pacific Island countries, such as a commitment to limit temperature rise.95 The Agreement reaffirms "the goal of limiting global temperature increase well below 2 degrees Celsius, while urging efforts to limit the increase to 1.5 degrees."96 Twelve Pacific Island countries signed the Paris Agreement on April 22, 2016.97

The Pacific Islands Forum 2016 annual meeting continued the organization's focus on climate change. The Forum Communique included the following statement:

Leaders reiterated the importance of the Pacific Islands Forum in maintaining a strong voice considering the region's vulnerabilities to the impact of climate change. Leaders welcomed the Paris Agreement and reinforced that achieving the Agreement goal of limiting global temperature increases to 1.5°C above pre-industrialised levels is an existential matter for many Forum Members which must be addressed with urgency. Leaders congratulated the eight Forum countries that have ratified the Agreement and encouraged remaining Members and all other countries to sign and ratify the Agreement before the end of 2016 or as soon as possible. Leaders called for ambitious climate change action in and across all sectors and encouraged key stakeholders to prioritise their support for the implementation of key obligations under the Agreement. 98

Ocean Acidification

Climate change and sea level rise are not the only environmental challenges "substantially enhanced" by anthropogenic activity facing the region.99 Ocean acidification is likely to have a severe impact on Pacific Island states. According to some experts, carbon dioxide, absorbed by seawater, creates acidification which in turn reduces the ability of many marine organisms, such as coral, from regenerating.100 Coral reefs play a key role in supporting fisheries and tourism which are two key components of the economy of many Pacific Island states. A recent study has found that coral cover in the Great Barrier Reef off the coast of Australia has declined by 50% over the past 30 years. Various studies have predicted that if current trends continue, ocean reefs will "be the first major ecosystem in the modern era to become ecologically extinct" by the end of the century. Others predict an earlier demise.101

Fisheries

The Southwest Pacific straddles the largest tuna fisheries in the world. According to one advocacy group, over half of the tuna consumed in the world is harvested from the Western and Central Pacific Ocean at an unsustainable rate.102 Many of the Pacific Islands states lack the capacity to effectively monitor and patrol their fisheries resources. In one example, Palau, a nation with a land area of 177 square miles and a maritime exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of 230,000 square miles, has a maritime police division of 18 personnel and one patrol ship. The global black market for seafood is estimated to be worth $20 billion with one in five fish caught illegally.103 As a result, poaching of fisheries is a major problem in the Pacific. In order to minimize poaching, the United States and nine Pacific Island states have entered into ship rider agreements. Under the program, enforcement officials from Pacific Island states may ride U.S. Coast Guard ships while they are patrolling the EEZs of those states. U.S. Coast Guard ships are empowered to enforce the laws of the host nation.104

Referenda on Self-Determination

New Caledonia, a territory of France, and Bougainville, which is part of Papua New Guinea, are to hold referenda on independence in 2018 and 2019. Issues and areas of possible concern to Congress include U.S. assistance for the administration of free and fair elections, the building of political institutions, and the mitigation of potential conflict. Developments in Bougainville also may affect U.S. relations with Papua New Guinea.

New Caledonia

The French Overseas Territory of New Caledonia, annexed by France in 1853 and formerly used as a penal colony for French convicts, may become the world's next state. An estimated 39% of New Caledonia's 260,000 people are Kanaks while 27% are European, with the balance composed of "mixed race" persons and others from elsewhere in the Asia-Pacific.105 In the 1980s, the indigenous Kanaks clashed with pro-France settlers. In a referendum in 1987, which was boycotted by local independence groups, New Caledonians voted to remain with France.106 Under the Noumea Accord of 1998, signed by France, the Kanak Socialist Liberation Front, and the territory's anti-independence RCPR Party,107 a referendum on independence must be held by the end of 2018.

Bougainville

The Bougainville conflict between the Papua New Guinea Defense Force and the pro-independence Bougainville Revolutionary Army began over disputes related to the Panguna copper mine on Bougainville in the late 1980s. Key grievances related to the mine included the influx of workers from elsewhere in Papua New Guinea and Australia, environmental damage caused by the mine, and Bougainville islanders' dissatisfaction with their share of mine revenue.108 Tensions over the mine and secessionist sentiment led to a decade-long, low-intensity war in which an estimated 10,000 to 20,000 government troops, militants, and civilians died. Peace between the government and rebels was restored in 1997 under a New Zealand-brokered agreement.109 Under the terms of the agreement, a referendum on self-determination is to be held by mid-2020. A target date of June 2019 has now been agreed to by the Papua New Guinea government and Bougainville regional government.110 Some factions reportedly have held onto their weapons out of concern that the PNG government will not go through with the referendum.111

Appendix. Social and Economic Indicators

|

Country |

Population |

GDP per capita |

Life Expectancy |

|

Papua New Guinea |

6,672,429 |

2,700 |

67 |

|

Fiji |

909,389 |

9,000 |

72 |

|

Solomon Islands |

622,469 |

1,900 |

75 |

|

Vanuatu |

272,264 |

2,500 |

73 |

|

Samoa |

197,773 |

5,200 |

73 |

|

Tonga |

106,501 |

5,100 |

76 |

|

Kiribati |

105,711 |

1,800 |

65 |

|

Micronesia |

105,216 |

3,000 |

72 |

|

Marshall Islands |

72,191 |

3,200 |

72 |

|

Palau |

21,265 |

15,100 |

72 |

|

Tuvalu |

10,869 |

3,400 |

66 |

|

Cook Islands |

9,838 |

12,300 |

75 |

|

Nauru |

9,540 |

14,800 |

66 |

|

Niue |

1,190 |

5,800 |

n/a |

Source: Central Intelligence Agency, The World Factbook, 2016.

Note: PPP = Purchasing Power Parity