The Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC) is a wholly owned U.S. government corporation that seeks to promote economic growth in less developed economies through the mobilization of private capital, in support of U.S. foreign policy goals.1 It is often referred to as the U.S. government's development finance institution (DFI).2

OPIC's enabling legislation is the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 (P.L. 87-195), as amended.3 The Foreign Assistance Act provides OPIC with authority to conduct its activities for a renewable period of time (see Appendix A).4 Over the past several years, Congress has extended OPIC's authority through appropriations law. Most recently, an FY2017 continuing resolution extended OPIC's authority through April 28, 2017 (P.L. 114-254).

The Foreign Assistance Act directs OPIC to "mobilize and facilitate the participation of United States private capital and skills in the economic and social development of less developed countries and areas, and countries in transition from nonmarket to market economies ... under the policy guidance of the Secretary of State."5 OPIC works to fulfill its mandate by providing political risk insurance, project and investment funds financing, and other services to promote U.S. direct investment overseas. Its services are intended to mitigate the risks affecting U.S. international investment, such as political risks (including currency inconvertibility, expropriation, and political violence), for U.S. firms making qualified investments overseas.6 OPIC characterizes itself as "demand-driven," providing services based on user interest. OPIC's activities may support U.S. exports, and it is involved in U.S. trade promotion interagency processes and initiatives.7

Congress does not approve individual OPIC projects, but has authorization, appropriations, oversight, and other legislative responsibilities related to the agency and its activities. Congress authorizes OPIC's ability to conduct its credit and insurance programs for a period of time that it chooses; can amend or change its governing legislation as it deems appropriate; and approves an annual appropriation for OPIC that sets an upper limit on the agency's administrative and program expenses, which are covered by OPIC's own funds. The Senate confirms presidential appointments to OPIC's Board of Directors and to the OPIC positions of president and executive vice president. The 115th Congress may take up a number of issues related to OPIC, chief of which could be whether to renew OPIC's authority and, if so, under what terms. Congress also may examine OPIC's financial product offerings, policies, activity composition, and organizational structure, among other issues.

This report is structured into three parts: (1) OPIC background; (2) international context for development finance; and (3) key issues for Congress related to OPIC.

Background

Origins

The U.S. government's role in overseas investment financing predates the formal establishment of OPIC. The Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 (P.L. 87-195) authorized the President to issue investment guarantees to support economic development overseas until June 30, 1964. Annual Foreign Assistance Acts for 1964-1968 extended this authority on a single-year basis.

Then, in the Foreign Assistance Act of 1969 (P.L. 91-175), Congress established OPIC in law, authorizing it until June 30, 1974. OPIC began operations in 1971 as a development finance institution amid an atmosphere of congressional disillusionment overall with U.S. aid programs, especially large infrastructure projects.8 In his first message to Congress on aid, President Nixon recommended the creation of OPIC to assume the investment guaranty and promotion functions that were being conducted by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). President Nixon also directed that OPIC would provide "businesslike management of investment incentives" to contribute to the economic and social progress of developing nations.9

In creating OPIC, the Nixon Administration indicated that it was not attempting to end official U.S. foreign assistance, because "private capital and technical assistance cannot substitute for government assistance programs," a combination that can provide "official aid on the one hand, and private investment and technical assistance on the other." Private investment activities, however, were meant to complement the official assistance programs and, thereby, multiply the benefits of both. In addition, market-oriented private investment was viewed as an antidote to the government-oriented aid projects that were considered by some to be costly and inefficient. OPIC was created as a first step in the eventual overhaul of the entire U.S. aid program. In 1973, this overhaul was completed, as the United States largely abandoned infrastructure building and other large capital projects in favor of humanitarian aid to meet basic human needs.10

Authorization Status

|

During 1961-2007, Congress extended OPIC's authority on numerous occasions on a multi-year basis, generally ranging from two to four years. On some occasions, Congress extended OPIC's authority for a shorter period during this time frame. (See Appendix A for authorization legislation for the 1961-2007 time frame.) Extensions of OPIC's authority occurred in various forms, but appear to have had substantially the same effect of allowing OPIC to continue operating. Some extensions were through laws specifically listed in the "Amendments" section to 22 U.S.C. §2195 (thus amending the Foreign Assistance Act). These included extensions in OPIC-specific legislation, legislation focused on foreign affairs or international trade more broadly, and appropriations legislation. Other extensions, particularly in more recent years, took the form of authorization "waivers" (as characterized by OPIC) in appropriations acts that allowed OPIC's functions to remain in effect but did not amend OPIC's sunset date in the Foreign Assistance Act. There appear to be a few "gaps" in legislation extending OPIC's sunset date, such as in 1981, 1985, and 1992. These possible gaps in authority appear to have been for a few weeks to a few months. Unlike the gap in 2008 (noted above), it is not clear whether these possible gaps affected OPIC's authority to conduct its functions. |

OPIC operates on a renewable basis under the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, as amended (22 U.S.C. §2191 et seq.). The Foreign Assistance Act includes a provision authorizing OPIC to perform certain functions until its sunset date, which Congress has periodically extended. That provision, in 22 U.S.C. §2195(a)(2), currently states, "The authority of subsections (a), (b), and (c) of section 2194 of this title [political risk insurance, loan guarantees, and direct loans, respectively] shall continue until September 30, 2007."

This sunset date reflects the last extension of OPIC's authority on a multi-year basis; the OPIC Amendments Act of 2003 (P.L. 108-158) extended OPIC's authority for nearly four years until September 30, 2007. Since 2007, OPIC generally has continued operating based on extensions of its authority in appropriations law, which OPIC has characterized as authorization "waivers."11 (One exception was a six-month period in 2008 when its authority lapsed.)12 These "waivers" have occurred through consolidated appropriations acts and continuing resolutions (CRs). For instance, Section 7061(b) of the FY2016 Consolidated Appropriations Act extended OPIC's authority until September 30, 2016; it stated, "Notwithstanding section 235(a)(2) of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, the authority of subsections (a) through (c) of section 234 of such Act shall remain in effect until September 30, 2016" (P.L. 114-113). FY2017 CRs subsequently extended OPIC's authority, most recently through April 28, 2017.

Programs

OPIC categorizes its operations into three main programs—insurance, finance, and investment funds—that are intended to promote U.S. private investment in less developed countries by mitigating risks, such as political risks, for U.S. firms making qualified investment overseas. OPIC's authority to guarantee and insure U.S. investments abroad is backed by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government and OPIC's own financial resources.

While private sector markets exist for financing and insuring U.S. direct investment overseas, there may be gaps in them due to "market failures" such as imperfect information, barriers to entry, risk levels, and financial crises. OPIC's primary objective in operating its programs is to promote economic development in low-income countries by supporting investment in projects, economic sectors, regions, and countries that are underserved by private markets; and mobilizing private investment in countries with viable project environments, but low credit ratings. For example, individual firms may attach more risk to investing in developing economies due to imperfect information and, thus, be unwilling to commit resources to investments in the least developed countries without risk mitigation by OPIC through its programs.13

Political Risk Insurance

OPIC provides political risk insurance to safeguard investments against certain political risks involved in investing in developing countries in three broad areas:

- Currency inconvertibility coverage compensates investors if new currency restrictions are imposed which prevent the conversion and transfer of remittances from insured investments, but does not protect against currency devaluation.

- Expropriation coverage protects U.S. firms against the nationalization, confiscation, or expropriation of an enterprise, including actions by foreign governments that deprive an investor of fundamental rights or financial interests in a project for a period of at least six months. This coverage excludes losses that may arise from lawful regulatory or revenue actions by a foreign government and actions instigated or provoked by the investor or foreign firm.

- Political violence coverage compensates U.S. citizens and firms for property and income losses directly caused by various kinds of violence, including declared or undeclared wars, hostile actions by national or international forces, civil war, revolution, insurrection, and civil strife (including politically motivated terrorism and sabotage). Income loss insurance protects the investor's share of income from losses that result from damage to the insured property caused by political violence. Assets coverage compensates U.S. citizens and firms for losses of or damage to tangible property caused by political violence. OPIC also has a number of special programs that protect U.S. banks from political violence. This type of insurance reduces risks for banks and other institutional investors, which allows them to play a more active role in financing projects in developing countries. Specialized types of insurance coverage also are available for U.S. investors involved with certain contracting, exporting, licensing, or leasing transactions that are undertaken in a developing country.

OPIC provides political risk insurance with terms of up to $250 million per project for up to 20 years, with premium rates guaranteed for the life of the contract. OPIC can insure up to 90% of a qualifying investment; OPIC's enabling legislation generally requires that investors bear at least 10% of the risk of loss.14 Political risk insurance from OPIC is available to U.S. citizens, U.S. firms that are at least majority beneficially owned by U.S. citizens, foreign subsidiaries of U.S. firms as long as the foreign subsidiary is at least 95% owned by U.S. entities or citizens, or other foreign entities that are 100% owned by U.S. entities or citizens.15

Investment Financing

OPIC's investment financing program operates like an investment bank, customizing and structuring a complete package for individual projects in countries where conventional financing institutions often are unwilling or unable to lend on a basis that is competitively advantageous for investors. OPIC provides financing to investors through direct loans and loan guarantees of up to $50 million for up to 20 years. It has specific programs for small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Most OPIC financing for a "non-financial" industry project (e.g., energy, manufacturing, transportation) is used to cover capital costs, such as facility construction or leasehold improvements, equipment, and design and engineering services associated with establishing or expanding a project. For a financial industry project, OPIC may provide financing to support lending capacity expansion, such as for microfinance, SME lending, or mortgage lending.16

To obtain OPIC financing, the venture must be commercially and financially sound and have meaningful U.S. involvement. OPIC generally defines "U.S. involvement" as a U.S.-organized entity that is 25% or more U.S.-owned, a foreign-organized entity that is majority U.S.-owned, U.S. citizens, lawful permanent residents, and U.S.-organized non-profit organizations. U.S. involvement in the project must be, at a minimum, equivalent to 25% of the project company's equity, which can be satisfied through equity investment, long-term debt investment, and/or other U.S. contracts, such as franchises.17

The amount of OPIC's participation may vary taking into consideration financial risks and benefits. In general, OPIC limits its support to 50% of the total investment, but may provide up to 75% in certain circumstances. Rates and conditions on loans and guarantees depend on financial market conditions at the time and on OPIC's assessment of the financial and political risks involved. Consistent with commercial lending practices, OPIC charges up-front, commitment, and cancellation fees, and reimbursement is required for project-related expenses.

Investment Funds

Investment funds are privately owned and managed sources of capital that make direct equity investments in portfolio companies in new, expanding, or privatizing companies in developing or emerging markets. OPIC supports these funds through financing to supplement the equity that the funds privately raise. In most instances, OPIC provides up to one-third of the fund's total capital, and receives debt returns on its investment. OPIC takes a senior creditor position.

OPIC supports these funds in situations where U.S. firms either cannot allocate or cannot raise sufficient capital to start or expand their businesses overseas. OPIC solicits these funds through a competitive "Call for Proposals" process that seeks investment funds focusing on the agency's development priorities, particularly in areas where investments have been difficult to obtain. OPIC uses the "Call for Proposals" process to select fund managers with private equity investment capability and experience. OPIC-supported investment funds cover a range of economic sectors, including financial services, insurance, housing, renewable energy, and information technology.18

OPIC approved its first investment fund in 1987.19 The investment funds program has been restructured periodically, such as in 2002, leading to the incorporation of the competitive selection process through the "Call for Proposals" (discussed above).20

Other Activities

OPIC conducts outreach to raise awareness of its programs and services for U.S. investors. For instance, OPIC offers workshops and seminars as part of its Expanding Horizons program to address concerns over political risks in emerging markets and share information about its programs and resources to support overseas investment. Expanding Horizons includes a focus on supporting U.S. small businesses in expanding to overseas markets.21

Statutory and Policy Conditions for OPIC-Supported Projects

Congress does not approve individual OPIC projects, but sets forth specific statutory requirements for OPIC in the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 (22 U.S.C. §2191 et seq.), as amended. OPIC also has various policy requirements for its support (see Table 1).

OPIC investment support falls outside of the international rules of the OECD Arrangement on Officially Supported Export Credits (the Arrangement)—which establishes guidelines for member countries' export credit agencies (ECAs), such as the Export-Import Bank of the United States (Ex-Im Bank).22 The Arrangement establishes limitations on terms and conditions of ECAs, including on minimum interest rates, maximum repayment terms, notification procedures, and reporting requirements for government-supported export credit activity that is directly tied to exports.23 Among other things, the Arrangement does not apply to investment support not directly linked or tied to procurement from the United States.24 Although OPIC's activities are considered to fall outside of the OECD Arrangement, they nevertheless may contribute to U.S. exports.

|

Requirement |

Description |

Statutory Basis |

|

OVERALL |

||

|

Mandate |

OPIC's mandate is "[t]o mobilize and facilitate the participation of United States private capital and skills in the economic and social development of less developed countries and areas, and countries in transition from nonmarket to market economies, thereby complementing the development assistance objectives of the United States... under the foreign policy guidance of the Secretary of State." |

22 U.S.C. §2191 |

|

Repayment |

OPIC is directed to operate "on a self-sustaining basis, taking into account in its financing operations the economic and financial soundness of projects[.]" |

22 U.S.C. §2191(a) |

|

TRANSACTION-SPECIFIC |

||

|

U.S. Connection |

According to OPIC, projects that it supports must have "meaningful involvement" by a U.S. citizen or business. OPIC's enabling legislation defines the term "eligible investor," and its policies provide further specifications. |

22 U.S.C. §2198(c) |

|

Economic Impact |

In determining whether to provide support, OPIC shall "be guided by the economic and social impact and benefits" of the project, and seek to support "those developmental projects having positive trade benefits for the United States[.]" OPIC must decline support if it determines that overseas investment may reduce employment in the United States, either because the U.S. firm shifts part of its production abroad, or because output from overseas investment will be shipped to the United States and "reduce substantially the positive trade benefits" of the investment. |

22 U.S.C. §2191(1); |

|

Environmental Impact |

OPIC generally is barred from participating in projects that pose an "unreasonable or major environmental health, or safety, hazard...." The Board of Directors cannot vote in favor of any project likely to have "significant adverse environmental impacts that are sensitive, diverse, or unprecedented" unless at least 60 days before the date of the vote, an environmental impact assessment of the project is conducted and made publicly available. |

22 U.S.C. §2191(n); |

|

Worker Rights |

Projects can be implemented only in countries that currently have, or are taking steps to adopt and implement, laws that uphold internationally recognized worker rights. A national economic interest determination waiver is possible by the President of the United States. |

22 U.S.C. §2191a(a) |

|

Human Rights |

OPIC is required to take into account in conducting its programs in a country, in consultation with the Secretary of State, "all available information about observance of and respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms in such country and the effect the operation of such programs will have on human rights and fundamental freedoms in such country." |

22 U.S.C. §2199(i) |

|

Small Business |

To the "maximum degree possible consistent with its purposes," OPIC must give preferential consideration to projects involving U.S. small business and to increase the proportion of projects significantly involving U.S. small business to at least 30% of certain of its activity. |

22 U.S.C. §2191(e) |

|

Additionality |

It is OPIC policy that its activities should complement, rather than compete with, the private sector, i.e., transactions that would otherwise be impossible or unlikely without its support. |

|

|

FOCUS AREAS AND LIMITATIONS |

||

|

Less Developed Countries |

OPIC must give preferential consideration to investment projects in less developed countries and restrict its support in other higher-income countries. However, OPIC, based on legislative history, interprets the statutory requirement as allowing it to support projects in higher income countries that are highly developmental, focus on underserved areas or populations, or support U.S. small business. |

22 U.S.C. §2191(2) |

|

Renewable Energy |

FY2010 appropriations language directed OPIC to "issue a report, not later than 180 days after December 16, 2009, highlighting its substantial commitment to invest in renewable and other clean energy technologies and plans to significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions from its portfolio," with the proviso that "such commitment shall include implementing a revised climate change mitigation plan to reduce greenhouse gas emissions associated with projects and sub-projects in the agency's portfolio as of June 30, 2008 by at least 30 percent over a 10-year period and by at least 50 percent over a 15-year period." (See "Coal-fired Power Plants" section immediately below.) |

P.L. 111-117, §7079(b); 22 U.S.C. §2191b |

|

Coal-fired Power Plants |

Since FY2014, appropriations legislation has prohibited the use of OPIC funds under certain conditions, for the enforcement of any rule, regulation, policy, or guidelines implemented pursuant to:

|

See, e.g., P.L. 114-113 , §7080(4) |

|

Sub-Saharan Africa |

The Board of Directors is directed to take "prompt measures" to increase OPIC programs and financial commitments in sub-Saharan Africa. |

22 U.S.C. §2193(e) |

|

Country Restrictions |

"From time to time, statutory and policy constraints may limit the availability of OPIC programs in certain countries, or countries where programs were previously unavailable may become eligible." |

|

|

Sectoral and Product Restrictions |

OPIC has "categorically prohibited sectors" based on economic, environmental, and other policy, e.g., projects established as a result of reducing or terminating U.S.-based operations. |

|

Source: OPIC's enabling legislation (22 U.S.C. §2191 et seq.), OPIC publications, GAO, Overseas Private Investment Corporation: Additional Acts Could Improve Monitoring Processes, GAO-16-64, December 2015, p. 10.

Notes: Descriptions provide summaries of the requirements and may not be comprehensive.

Portfolio Exposure

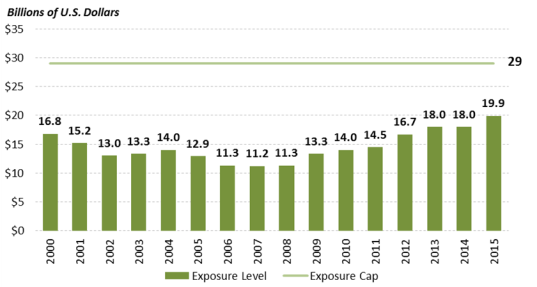

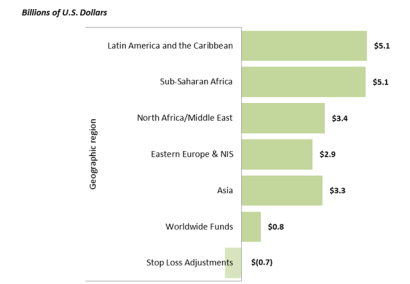

The statutory limit on the total contingent liability ("portfolio exposure") for OPIC's financing and insurance is $29 billion.25 In FY2015, OPIC's portfolio had a total exposure of nearly $20 billion, distributed across geographic regions (see Figure 1 and Figure 2).26 OPIC attributes the growth in its exposure in recent years to a combination of OPIC's efforts to "extend its development reach, capitalize on the growing appreciate for development finance and collaborate with more partners."27

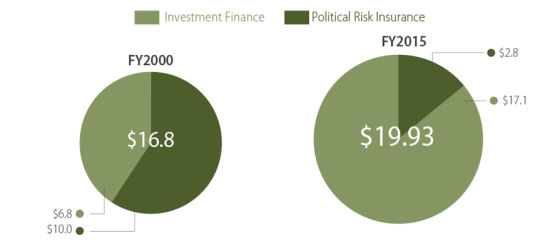

The composition of OPIC's portfolio by financial product type has evolved. In earlier years, political risk insurance constituted the larger share of OPIC's portfolio, but this share has declined as the global private political risk insurance market has developed and expanded.28 In contrast, investment financing has constituted the larger share of OPIC's portfolio (see Figure 3).29

Commitments of Finance and Insurance Support

In FY2015, OPIC made $4.4 billion in new commitments for investment projects. OPIC estimates that the 100 new projects it supported in FY2015 will bring $14.2 billion in new investment in 38 developing or emerging markets and create 20,000 permanent jobs in these host countries over the next five years. In terms of U.S. benefits, OPIC expects that its FY2015 commitments will support, over a five-year period, 401 U.S. jobs through the procurement of $264 million in goods and services from the United States.30 OPIC prioritizes its works based on U.S. foreign policy and development objectives, but is also demand-driven.

In FY2015, OPIC support was available in 161 developing and emerging economies and OPIC had active projects in about 100 countries.31 In terms of regions, sub-Saharan Africa represented the largest share of OPIC's new commitments both by value and number of commitments, followed by the Asia-Pacific region (see Table 2).

|

Value ($ millions) |

Number |

|

|

Sub-Saharan Africa |

$1,830 |

26 |

|

Asia and the Pacific |

$1,050 |

17 |

|

Middle East and North Africa |

$558 |

12 |

|

Latin America and the Caribbean |

$423 |

23 |

|

Eastern Europe |

$144 |

12 |

|

Multiple Regions |

Not specified |

10 |

Source: OPIC, FY2015 annual report and annual development impact report.

Notes: Regional categories vary among the two reports.

According to OPIC, the world's poorest countries (e.g., Rwanda, Cambodia, and Haiti) constituted close to half of its financial commitments in FY2015.32 OPIC reported that about one-third of its new FY2015 commitments by number were for projects in low-income countries (33%), the rest being in middle-income countries (46%) and high-income countries (21%)—based on statutorily defined country-income levels for OPIC.33 Regarding prior years, according to GAO, between FY2008 and FY2014, OPIC's new commitments for projects in low per capita income countries constituted about 34% of its total new commitments by number and 25% by value, with the remainder directed middle- and high- per capita income countries (also based on the statutorily defined country-income levels).34 In comparison, a separate study observes that when using World Bank-based classifications of country-income level, on a year-on-year basis for 2000-2014, the share of OPIC's commitments directed to the poorest countries has trended downward, while the share of OPIC's commitments directed toward higher-income countries in the OECD (e.g., Chile, Israel, Mexico, Turkey) has increased, with much of the support focused on renewable energy projects.35 According to the study, the decline in the share of the poorest countries could be attributed to certain "macro-level trends," the existence of fewer low-income countries now than before as countries develop economically, and many of the remaining low-income countries being small, fragile states.

OPIC is active in a range of economic sectors. In FY2015, the financial services sector accounted for the largest share (49%) of OPIC projects, with the majority of such projects focused on supporting SME and microfinance institution lending. The second-largest sector for OPIC projects was energy (19%).36 OPIC reported committing close to $1.1 billion for renewable energy projects specifically in FY2015.37 Other sectors in which OPIC is involved include manufacturing, infrastructure, services, agriculture, education, information technology, and health.

OPIC aims to expand U.S. SME involvement in overseas investment. In FY2015, U.S. SMEs accounted for nearly 75% of projects receiving OPIC support. OPIC also has focused on expanding financing available to SMEs in developing countries and emerging markets.

|

Examples of OPIC Participation in Administration Foreign Policy Initiatives In response to political change in the MENA region, OPIC pledged $2 billion of financial support to "catalyze private sector development" in the region and an additional $1 billion to support infrastructure and job creation specifically in Egypt.38 As part of these efforts, OPIC, for example, approved $500 million in lending to Egypt and Jordan ($250 million to each country) to support small businesses in those countries.39 The U.S.-Africa Clean Energy Finance (ACEF) Initiative—a joint mechanism by OPIC, along with the Department of State and the Trade and Development Agency (TDA)—is a four-year, $20 million program launched in June 2012 to catalyze private sector investment in the African clean energy sector by identifying and providing financing for project development costs. In 2013, OPIC dedicated a staff member for South Africa to support the initiative.40 The U.S.-Asia Pacific Comprehensive Partnership for a Sustainable Energy Future, announced during the 2012 East Asia Summit, is an initiative that includes up to $6 billion from federal trade and investment promotion agencies to finance exports and investments related to energy infrastructure in the region.41 OPIC stated that it will provide up to $1 billion in financing for sustainable power and infrastructure projects in the region, in support of the initiative.42 Power Africa, announced by the President in June 2013, is an initiative to double access to power in sub-Saharan Africa through U.S. government commitments of more than $7 billion. OPIC has surpassed its initial target of $1.5 billion in commitments and now has an enhanced goal of committing an additional $1 billion for the initiative by 2018.43 Look South, announced in January 2014, is a Department of Commerce-led federal government initiative to help more companies do business with Mexico and the United States' other free trade agreement partners in Latin America. Among other things, it aims to increase availability and awareness of investment tools through OPIC.44 |

Budget

Congress directs OPIC to operate "on a self-sustaining basis, taking into account in its financing operations the economic and financial soundness of projects."45 OPIC's budget is funded from its offsetting collections, which are derived from the premiums, interest, and fees generated from its insurance and finance services and the accumulated interest generated from the agency's investment in U.S. Treasury securities.46 Its budget is composed of noncredit and credit accounts, in conformity with the standards set out in the Federal Credit Reform Act of 1990 (FCRA). The noncredit portion relates to OPIC's political risk insurance program, while the credit portion is comprised of OPIC's direct and guaranteed loans. OPIC uses premium income and the interest it accrues from the assets in its noncredit account to fund the direct and indirect expenses in its noncredit and credit accounts.

While OPIC has the authority to spend from its own revenue to cover its operations, Congress and the President set OPIC's maximum spending levels for its administrative and program expenses through the annual appropriations process. The FY2016 appropriations act provided $62.8 million for OPIC's administrative expenses to carry out its credit and insurance programs and a transfer of $20 million from its noncredit account for credit program costs. In FY2016, OPIC had a staff of 289 full-time equivalents (estimate) (see Table 3).

|

FY11 |

FY12 |

FY13a |

FY14 |

FY15 |

FY16 |

FY17 |

|

|

Noncredit Account: |

|||||||

|

Amount requested |

$53.9 |

$57.9 |

$60.8 |

$71.8 |

$71.8 |

$83.5 |

$88.0 |

|

Amount appropriated |

$52.3 |

$54.99 |

$54.99 |

$62.6 |

$62.8 |

$62.8 |

CRb |

|

Credit Account: |

|||||||

|

Amount requested |

$29.0 |

$31.0 |

$31.0 |

$31.0 |

$25.0 |

$20.0 |

$20.0 |

|

Amount appropriated |

$18.1 |

$25.0 |

$25.0 |

$27.4 |

$25.0 |

$25.0 |

CRb |

|

Staff |

|||||||

|

Direct civilian full-time equivalents |

205 |

220 |

229 |

223 |

257 |

289c |

350c |

Source: Budget of the United States Government and appropriations legislation, various years.

Notes:

a. Data for amounts appropriated do not reflect sequestration reduction.

b. CR: The further continuing resolution through April 28, 2017 (P.L. 114-254) contains an across-the-board reduction of 0.1901% in the rate of operations from the amount provided in FY2016 appropriations.

OPIC has a net negative budget authority; its offsets to budget authority have been greater than its appropriations. According to OPIC, it generated $434 million in "deficit reduction" for the U.S. government in FY2015, representing its 38th consecutive year of generating negative outlays.47

OPIC's loan disbursements are financed through two sources: the long-term loan subsidy costs are financed by its collections, and the remaining non-subsidized portion of the loans is financed by borrowings from the Treasury. OPIC finances investment guarantees by issuing certificates of participation in U.S. debt capital markets. OPIC repays the Treasury through collection of loan fees, repayments, and default recoveries. OPIC uses nonbudgetary "financing accounts" to account for credit program cash flow. The subsidy expense for a direct loan or loan guarantee is estimated when it is first disbursed. OPIC reestimates its total subsidy cost at regular intervals based on updated assumptions. Permanent indefinite authority is available to fund any reestimated increase of subsidy costs that occurs after the year in which a loan is disbursed. Reestimated reductions of subsidy costs are returned to the Treasury.48

Risk Management

OPIC seeks to promote private sector investment in developing and emerging economies through offering financial products that help to mitigate the political and commercial risks of making qualified investments overseas. As such, OPIC faces certain risks in its activities. Congress directs OPIC to "conduct its insurance operations with due regard to the principles of risk management...."49 OPIC assesses the credit and other risks of proposed transactions; monitors current commitments for risks; and seeks recoveries in instances where it pays or settles valid claims.50 OPIC also states that it budgets and accounts for risk in its credit portfolio through FCRA. Additionally, OPIC says that it offsets any potential future losses with reserves (comprised of U.S. Treasury securities), which cumulatively totaled $5.6 billion in FY2015.51

In its 44 years of operations, OPIC reports that it has expended more cash than it collected in two fiscal years.52 Based on its historical record and risk management practices, OPIC recognizes but considers unlikely the possibility, "that a significant credit or insurance event affecting multiple transactions could trigger net losses in [OPIC's] portfolio," resulting in costs exceeding collections in a future fiscal year.53

International Context for Development Finance

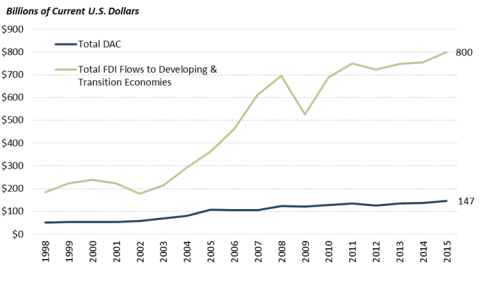

External financial flows to developing countries come through a number of channels. One is official development assistance (ODA) from foreign governments (e.g., grants, concessional lending).54 Another is private capital flows from foreign companies, including through foreign direct investment (FDI).55 In developing countries, ODA historically was the main source of external financing. Over time, FDI flows have grown relative to ODA flows (see Figure 4).56 Traditionally, FDI largely has flowed from developed countries to developing countries, but emerging markets and developing countries also are becoming significant FDI sources.57

Along with the changing international investment landscape, the international development policy landscape has evolved with bilateral and multilateral development financing institutions (DFIs) playing a more active role. DFIs are used here to refer to entities that provide officially backed (or government-backed) support (e.g., through direct loans, loan guarantees, or insurance) for private sector investment in less developed countries.58

It is difficult to find centralized, comprehensive sources of information on DFI activities. Officially backed investment financing activities are outside of the scope of the OECD Arrangement on Officially Supported Export Credits ("the Arrangement"), which includes notification procedures and reporting requirements on activity. Countries vary in terms of how much information they publish on their DFI activities.

The International Finance Corporation, using its database, estimated that private sector commitments (not including political risk insurance) by certain international financial institutions to developing countries grew from about $10 billion in 2002 to over $40 billion in 2010.59 A subsequent estimate by the Center for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS), which it said was based on the same set of institutions, pegged that total at about $68 billion in 2013.60

The level of DFI support through political risk insurance also may be significant. The Berne Union, an international group of private and state export credit and foreign investment insurers, maintains statistics on political risk insurance provided by its members linked to FDI.61 However, these data may include investment support not related to development finance, given the group's membership. According to the Berne Union, its members' newly underwritten investment insurance transactions reached $97 billion in 2015.62

While developed countries, such as the United States (through OPIC) and some other G-7 countries, traditionally have been the sources of development finance, emerging economies such as China, Brazil, and India also have become significant players in this space (see Appendix B). The growing number of development finance players and volumes of investment financing have resulted in greater and varied competition for U.S. businesses—competition from firms in both developed countries and in emerging economies as they move up the value chain. U.S. companies may seek OPIC assistance to counter the officially backed investment support that their competitors receive. At the same time, from an economic perspective, the role of government-backed financing and its impact on markets is debated.

Below are some general comparisons of OPIC and selected other DFIs; these comparisons are illustrative of the DFI landscape and not comprehensive.

- Ownership: OPIC and certain other DFIs are owned exclusively by the public sector, such as CDC (United Kingdom) and DEG (Germany). Others, such as FMO (the Netherlands) and Proparco (France), have joint public and private ownership. Regional and multilateral DFIs (such as EBRD and IFC) have multiple shareholders from various countries.

- Organizational Structure: Countries vary in how they organize their investment and export financing functions. The United States houses investment and export financing functions in separate entities, OPIC and Ex-Im Bank respectively. The two agencies have different missions—with OPIC focused more on foreign policy and development goals and Ex-Im Bank geared toward commercial goals—although they do coordinate on certain transactions. By comparison, some other countries house these functions in the same entity.63 For example, JBIC (Japan) conducts both investment and export financing operations.

- International Rules: As discussed earlier, the investment financing activities of DFIs fall outside of the forms of financing regulated by international disciplines through the OECD Arrangement on Officially Supported Export Credits. The Arrangement includes limitations on financial terms and conditions in areas such as down payments, repayment terms, interest rates and premia, and country risk classifications. It contains notification procedures and reporting requirements for countries' export credit activities to encourage transparency. Among other things, the OECD Arrangement does not apply to investment support not directly linked or tied to procurement from the country providing the official support.64

- Financial Instruments: OPIC provides investment support through direct loans, loan guarantees, and political risk insurance. In contrast, many other DFIs offer a larger suite of financial products, including participating as a limited partner in private equity funds. OPIC has previously stated that it is the only one of at least 30 private sector-focused DFIs without the ability to participate as a limited partner in private equity funds.65 For instance, the portfolios of most members of the European Development Finance Institutions (EDFI) contained support through equity or "quasi-equity" instruments at the end of 2015.66 In some cases, equity or quasi-equity was the primary focus of DFI activity. Additionally, some DFIs provide "project-specific and general technical assistance."67 OPIC provides limited technical support.

- Portfolio Size: The size of DFI portfolios varies. For example, OPIC's cumulative portfolio totaled nearly $20 billion in FY2015. In comparison, the 15 EDFI members collectively had a total portfolio of €36 billion (about $39 billion) at the end of 2015.68 In comparison, China appears to have the largest presence in international development finance, according to a study conducted by Boston University and the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. This study estimates that two Chinese "policy banks" had outstanding loans to overseas borrowers totaling $684 billion at the end of 2014, making available $106 billion in development finance. Ex-Im Bank's annual competitiveness report focuses on export financing, but includes some data on investment financing. Based on Ex-Im Bank estimates, in 2015, China's new investment support alone totaled $49 billion, exceeding that of other ECAs, which had $42 billion combined.69

- Portfolio Distribution: DFIs support projects in a range of economic sectors. DFIs traditionally have favored infrastructure, but have focused more recently on other sectors such as financial services (see above for OPIC composition). In 2015, the financial sector represented the largest sector of support in the portfolios of EDFI members collectively (30% of a €36 billion, or about $39 billion, portfolio) followed by power (18%), industry or manufacturing (16%), other infrastructure (11%), agribusiness (8%), services (5%), and other sectors (12%).70 In contrast, Chinese development finance is aimed mainly at infrastructure.71 Chinese government loans and related financing have been directed at constructing roads, rail, hospitals, schools, housing, and water and energy infrastructure, with the involvement of Chinese firms, including state-owned enterprises.72

- Policy Requirements: Requirements that projects must meet in order to receive support vary by DFI, such as with respect to environmental, worker rights, and other conditions. OPIC is widely regarded in the development finance community as having among the most extensive policy requirements for projects to receive its support. According to OPIC, it has been a leader among DFIs in "developing and applying environmental and social policies that advance long-term sustainable development."73 EDFI states that its European DFI members have adopted a "shared set of principles for responsible financing, which underlines that respect for human rights and environmental sustainability is a prerequisite for financing by EDFIs."74 In terms of China's development finance regime, for example, "[d]ue to in-country dynamics, corruption, or disparate standards frameworks, some Chinese development projects have produced adverse outcomes for the environment, labor, and local livelihoods..."75

Issues for Congress

OPIC presents a number of possible issues for Congress, chief of which could be a debate about its reauthorization. Congress also may examine OPIC's product offerings, policy requirements for supporting projects, activity composition, and organizational structure.

Reauthorization

Congress may examine whether to reauthorize OPIC and, if so, the length of time for which to extend its authority and under what terms. In recent years, Members of Congress have introduced various types of bills concerning OPIC's authority (see text box). Congressional views differ on the justifications for and against OPIC.

One issue is the relationship between OPIC and the private sector.76 Supporters argue that OPIC fills gaps in private sector political risk insurance and financing for investment and helps "level the playing field" for U.S. businesses competing against foreign companies supported by their own DFIs, while critics argue that OPIC distorts the flow of capital and resources away from efficient uses and crowds out viable, private sector alternatives for investment financing and insurance. Those in favor of OPIC also assert that it provides support for projects, markets, and sectors where government-backed financing and insurance can make the most difference (e.g., large-scale, long-term infrastructure projects, investments by small businesses, projects in developing countries, and during financial crises), while those critical of OPIC point out that the majority of U.S. overseas investments occur without OPIC support and question why OPIC should take on risk when the private sector does not want to.

|

Bills Related to OPIC's Authority Several bills entitled the "Electrify Africa Act of 2015" were introduced in the 114th Congress. The bills aimed to increase U.S. government support, including through OPIC, to assist sub-Saharan African countries in expanding electricity access to support economic growth and other goals. Two of the bills, H.R. 2847 and S. 1933, would have extended OPIC's authority through FY2018. In contrast, S. 2152 did not include any extension of OPIC's authority; this bill became law in February 2016 (P.L. 114-121). |

Other issues include the composition of OPIC's activities and its outcomes. Supporters argue that U.S. companies of all sizes benefit from OPIC and that OPIC charges interest, premia, and other fees for its support, while critics contend that OPIC, as a form of government intervention, is "corporate welfare" and that, by dollar value, larger companies are the primary beneficiaries. Supporters note OPIC's risk management practices and record, while critics express concern about the potential risks that OPIC's activities pose to U.S. taxpayers. Also, supporters argue that OPIC screens projects for "additionality" and that its activities contribute to U.S. jobs and exports, while critics question OPIC's opportunity costs and express concern that OPIC supports companies whose overseas investments may result in the outsourcing of U.S. jobs.

From a foreign policy perspective, supporters contend that OPIC's activities, on a demand-driven basis, advance U.S. development and national security interests by contributing to economic development in poor countries, while critics counter that the actual composition of OPIC's activities may not reflect U.S. foreign policy priorities and that the development benefits of OPIC's activities are questionable.77

From an operational standpoint, some argue that OPIC would benefit from multi-year authorizations and "that the potential risk of a lapse undermines the private sector's confidence in OPIC's effectiveness, given that clients and projects require long-term planning and exit horizons."78 Others argue that shorter extensions may provide opportunity for Congress to weigh in more frequently on OPIC operations through the lawmaking process. Questions may be raised about the extent that yearly renewals of authority through the appropriations process affect OPIC and what issues may be discussed in a broader debate about OPIC's authority. Congress also may evaluate the impact of a lapse or expiration of OPIC's authority. For instance, OPIC's authority lapsed during April-September 2008. During this period, OPIC was able to disburse funds for already committed projects, but was unable to sign contracts for new projects.79 This lapse in authority reportedly contributed to a backlog of projects in OPIC's pipeline of, by one estimate, about $2 billion of potential transactions.80

Product Offerings

OPIC currently provides political risk insurance, project and investment funds financing through direct loans and loan guarantees, and other services. Congress may consider whether to adjust OPIC's product offering.

Equity Authority. A long-standing topic of debate is whether OPIC should be able to make equity investments in investment funds, in addition to the current debt financing that it provides for such funds.81 According to OPIC, it currently does not have resources to make limited partnership investments.82 OPIC's FY2017 congressional budget justification includes a request for authority to use up to $20 million from its Credit Reform Appropriation and $20 million in transfer authority to invest in private equity funds that serve OPIC's mission. Proponents argue that equity authority would enable OPIC to exert greater influence in an investment's strategic goals and economic, social, and governance policies; that foreign counterparts, many of whom have equity authority,83 may be more likely to partner with OPIC on projects, increasing OPIC's ability to leverage its resources; and that OPIC could use the higher returns generally associated with equity investments to support more projects. Critics may raise concerns about the U.S. government taking an ownership stake in a private enterprise, the greater resources required for equity investments, and the greater risks and financial exposure that equity investments entail.

Technical Assistance. Another point of debate is whether OPIC should have a consistent ability to provide grants, such as for technical assistance, for the projects that it supports. Those in favor of such proposals contend that providing technical assistance would enhance OPIC's effectiveness in supporting projects.84 On the other hand, critics contend that providing OPIC with a significant grant function would duplicate the roles of USAID and TDA in development assistance.

Policies

In supporting U.S. private sector investment overseas, OPIC seeks to balance multiple policy objectives, including foreign assistance, development, economic, environmental, and other policy goals. Congress could evaluate how OPIC might prioritize and balance these various objectives.

OPIC's environmental policies on greenhouse gas (GHG) emission reductions (which some stakeholders refer to as a "carbon cap"), in particular, have been the subject of congressional action and vigorous stakeholder debate (see text box). On one hand, such efforts may serve U.S. environmental policy goals and help to improve the sustainability of OPIC's activities. On the other hand, some U.S. businesses argue that the GHG emissions reduction effort can constrain their ability to utilize OPIC support and place them at a competitive disadvantage vis-à-vis foreign firms when competing for international project contracts (e.g., major infrastructure projects in sub-Saharan Africa). Other DFIs generally do not have the same level of policy restrictions that OPIC has, potentially enabling them to support a broader array of energy-related projects. From a development perspective, some argue that the GHG emission reduction effort prevents OPIC from supporting projects likely to have the largest development impact.

|

OPIC's Environmental Policy Based on FY2010 appropriations (P.L. 111-117, §7079(b)) and other factors, OPIC has engaged in efforts to reduce the direct GHG emissions associated with projects in its active portfolio (i.e., all insurance contracts in force and all guaranty and direct loans with an outstanding principal balance) by 30% over a 10-year period (June 30, 2008-September 30, 2018) and by 50% over a 15-year period (June 30, 2008-September 30, 2023).85 Since FY2014, appropriations acts have prohibited the use of OPIC funds under certain conditions, until September 30, 2016, for enforcing any rule or guideline implementing (1) OPIC's GHG reductions policy; or (2) OPIC's proposed modification to its Environmental and Social Policy Statement (ESPS) related to coal.86 As such, the use of appropriated funds by OPIC to implement the GHG emissions reduction policy and proposed coal-related modification to the ESPS is not allowed if the implementation would prohibit (or have the effect of prohibiting) any coal-fired or other power-generation projects that satisfy two conditions: (1) the project's purpose is to "provide affordable electricity in International Development Association (IDA)-eligible countries and IDA-blend countries";87 and (2) the project's purpose is to "increase exports of goods and services from the United States or to prevent the loss of jobs from the United States." For example, see the FY2016 appropriations act (P.L. 114-113 , §7080(4)). The appropriations ban could lead to more opportunities for OPIC support for overseas coal-related projects in developing countries. Some stakeholders may favor the prohibition because they view it as giving OPIC greater flexibility to more effectively meet its development mandate and, in turn, support U.S. jobs and growth, while others may oppose it for environmental reasons. |

Activity Areas

One area of congressional interest could be whether OPIC's portfolio has an appropriate mix in terms of its development objectives and is directed sufficiently to those areas in which it may be most needed. Some stakeholders, for example, have expressed concern about what they see as OPIC's shift away from projects in sectors commonly viewed as contributing to poverty reduction (e.g., agriculture, infrastructure, and transportation) and toward projects in other sectors where development benefits may be less clear (e.g., finance and hotels). Drivers of such trends may have been environmental policies constraining support for large-scale infrastructure projects, as well as the need to balance financial risks and be self-sustaining. Congressional concern was voiced, for example, about OPIC's support for projects that do not necessarily, on their face, appear to align with OPIC's development mission, such as the construction of a shopping mall in Jordan, expanded billboard advertising in Ukraine, and hotels in Armenia and Georgia.88 Others may counter that OPIC conducts development impact assessments of proposed projects and monitors the development impact of existing projects; they also may point to the development impacts of projects discussed in OPIC's annual policy reports, for instance in terms of host country employment.89

Another area of interest could be considering opportunities for enhancing OPIC's support for specific geographical areas or sectors that are of U.S. policy priority. For example, the Electrify Africa Act of 2015 (P.L. 114-121), among other things, directs OPIC to prioritize and expedite its support for power projects in sub-Saharan Africa. On one hand, greater resources may increase capacity to promote investment, but on the other hand, federal agencies' allocation of funds for trade and investment promotion is generally demand-driven. Thus, for example, if U.S. firms do not seek such assistance due to lack of sufficient commercial interest, such funds may not be fully tapped. At the same time, promotion of development finance opportunities by OPIC could motivate U.S. companies to become more engaged.

Organizational Structure

OPIC's organizational structure may present possible areas of congressional consideration, including in the following areas.

Reorganization. During the presidential campaign, President-elect Trump proposed to consolidate trade-related agencies and departments into one office called the "American Desk" under the Department of Commerce.90 The general contours of the Trump proposal appear to be reminiscent of President Obama's call for reorganization authority to reorganize and consolidate, into one department, the trade-related functions of OPIC and five other federal entities into one department to streamline the federal government and make it more effective.91 The proposal, however, did not gain much traction in Congress, largely due to concerns about its implications for the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) and its U.S. trade negotiation and enforcement functions. Other proposals offered by stakeholders include consolidating federal agencies focused on promoting international development through private sector tools (such as OPIC, TDA, and certain elements of USAID), and/or creating a "development finance agency."92 Such proposals raise debates about whether reorganization would reduce costs and improve the effectiveness of trade policy programs, or undermine their effectiveness given the differing missions of federal trade agencies.93

Privatization or Termination. Other possible options include privatizing or terminating OPIC, the feasibility of which previously has been analyzed.94 Supporters of such options may argue that OPIC's self-sustaining nature is proof that there is no market failure; that OPIC competes with or crowds out the private sector, which is more efficient and better suited than the federal government to support investments; and that OPIC's activities impose potential costs and risks on U.S. taxpayers, since they are backed by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government.95 Those in favor of OPIC may argue that the federal government plays a unique role in addressing market failures; that OPIC's backing by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government may make certain transactions more commercially attractive or give OPIC leverage to guarantee repayment in a way that is not available to the private sector; and that federal investment support is critical when there is a shortfall in private sector financing and insurance.

Internal Oversight. OPIC's own internal oversight structure presents another area of interest. USAID's Inspector General has legal authority to conduct reviews, investigations, and inspections of OPIC's operations and activities, while external auditors conduct audits of OPIC's financial statements and report findings to OPIC's Board of Directors.96 One possibility is establishing an OPIC-specific Inspector General.97 Some may support this approach given differences in OPIC's private sector financing focus and USAID's grant-making functions. Opponents may assert that the current OPIC-USAID arrangement suffices or express concern about the additional resources a new Inspector General could require. Other possibilities include directing Ex-Im Bank's Inspector General to conduct OPIC oversight. Some may support this on the basis that Ex-Im Bank and OPIC offer some similar financing and insurance products, though others may express concern because of differences in the two agencies' missions and stakeholders.

Appendix A. OPIC Authorization History98

OPIC operates on a renewable basis under the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, as amended (22 U.S.C. §2191 et seq.). The Foreign Assistance Act includes a provision authorizing OPIC to perform certain functions until its sunset date, which Congress has periodically extended. That provision, in 22 U.S.C. §2195(a)(2), currently states, "The authority of subsections (a), (b), and (c) of section 2194 of this title [political risk insurance, loan guarantees, and direct loans, respectively] shall continue until September 30, 2007."

This sunset date reflects the last extension of OPIC's authority on a multi-year basis; the OPIC Amendments Act of 2003 (P.L. 108-158) extended OPIC's authority for nearly four years until September 30, 2007. Since then, OPIC generally has continued operating based on extensions of its authority in appropriations law, which OPIC has characterized as authorization "waivers."99 (One exception was a six-month period in 2008 when its authority lapsed.)100 These "waivers" have occurred through consolidated appropriations acts and continuing resolutions (CRs). For instance, Section 7061(b) of the FY2016 Consolidated Appropriations Act extended OPIC's authority until September 30, 2016; it stated, "Notwithstanding section 235(a)(2) of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, the authority of subsections (a) through (c) of section 234 of such Act shall remain in effect until September 30, 2016" (P.L. 114-113). Most recently, an FY2017 continuing resolution extended OPIC's authority through April 28, 2017 (P.L. 114-254).

Table A-1 provides a list of legislation identified by CRS as creating OPIC and extending its authority during 1961-2007, as well as the associated statutory text and new sunset date. To identify the legislation in this table, CRS examined the notes of Title 22 sections 2194 and 2195 of the U.S. Code, and searched Congress.gov and ProQuest Congressional for additional pieces of legislation extending OPIC's authority. While all efforts were made to ensure the comprehensiveness of this list, the presence of any gaps in authorization legislation should not be regarded as determinative of OPIC's authorization status.

During 1961-2007, Congress extended OPIC's authority on numerous occasions on a multi-year basis, generally ranging from two to four years. On some occasions, Congress extended OPIC's authority for a shorter period during this time frame. Extensions of OPIC's authority occurred in various forms, but appear to have had substantially the same effect of allowing OPIC to continue operating. Some extensions were through laws specifically listed in the "Amendments" section to 22 U.S.C. §2195 (thus amending the Foreign Assistance Act). These included extensions in OPIC-specific legislation, legislation focused on foreign affairs or international trade more broadly, and appropriations legislation. Other extensions, particularly in more recent years, took the form of authorization "waivers" (as characterized by OPIC) in appropriations acts that allowed OPIC's functions to remain in effect but did not amend OPIC's sunset date in the Foreign Assistance Act.

In a few instances, there appear to be "gaps" in legislation extending OPIC's sunset date, such as in 1981, 1985, and 1992. These possible gaps in authority appear to have been for a few weeks to a few months. Unlike the gap in 2008 (noted above), CRS has not been able to determine whether these possible gaps affected OPIC's authority to conduct its functions.

|

Legislation |

Enacted |

Sunset Date |

|

Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 |

September 4, 1961 |

June 30, 1964 Law authorized President to issue investment guarantees to support economic development overseas, prior to establishment of OPIC. SEC. 221. GENERAL AUTHORITY.— (a) In order to facilitate and increase the participation of private enterprise in furthering the development of the economic resources and productive capacities of less developed friendly countries and areas, the President is authorized to issue guaranties as provided in subsection (b) of this section of investments in connection with projects, including expansion, modernization, or development of existing enterprises, in any friendly country or area with the government of which the President has agreed to institute the guaranty program. The guaranty program authorized by this title shall be administered under broad criteria, and each project shall be approved by the President. ...Provided further, That this authority shall continue until June 30, 1964. |

|

Foreign Assistance Acts of 1964-1968 |

P.L. 88-633, October 7, 1964 P.L. 89-171, September 6, 1965 P.L. 89-583, September 19, 1966 P.L. 90-137, November 14, 1967 P.L. 90-554, October 8, 1968 |

June 30, 1971 (Annual Foreign Assistance Acts reauthorized this general authority on a single-year basis, for 1964-1968. The 1968 Act [P.L 90-554] reauthorized until June 30, 1971.) P.L. 90-554: SEC. 103. (a) Section 221(b) of title III of chapter 2 of part I of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, as amended, which relates to general authority for investment guaranties, is amended as follows: ... (C) In the last proviso, strike out "1970" and substitute '1971--. |

|

Foreign Assistance Act of 1969 |

December 30, 1969 |

June 30, 1974 Law specifically established OPIC. H. Rept. 91-611 stated: "this bill creates a new Overseas Private Investment Corporation to take over the Agency for International Development's (AID's) present U.S. investment incentive programs and carry out other activities..." (p. 3). Sec. 235. Issue Authority Direct Investment Fund and Reserves. (4) The authority of section 234 (a) and (b) shall continue until June 30, 1974. (On January 19, 1971, the President transferred rights and responsibilities, outlined in the Foreign Assistance Act, to OPIC [Executive Order 11579, January 19, 1971].) |

|

Foreign Assistance Act of 1973 |

December 17, 1973 |

December 31, 1974 In section 235(a) (4), strike out "June 30, 1974" and insert in lieu thereof "December 31, 1974[.]" |

|

OPIC Amendments Act of 1974 |

August 27, 1974 |

December 31, 1977 (3) In section 235---(A) strike out "1974" in subsection (a)(4) and insert in lieu thereof "1977[.]" |

|

Foreign Assistance and Related Programs Appropriations Act 1978 (P.L. 95-148) |

October 31, 1977 |

September 30, 1978 Title I: For expenses necessary to enable the President to carry out the provisions of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, as amended, and for other purposes, to remain available until September 30, 1978, unless otherwise specified herein, as follows: ... Title II: ... The Overseas Private Investment Corporation is authorized to make such expenditures within the limits of funds available to it and in accordance with law (including not to exceed $10,000 for entertainment allowances), and to make such contracts and commitments without regard to fiscal year limitations as provided by section 104 of the Government Corporation Control Act, as amended (31 U.S.C. 849) as may be necessary in carrying out the program set forth in the budget for the current fiscal year. |

|

OPIC Amendments Act of 1978 |

April 24, 1978 |

September 30, 1981 SEC. 4. Section 235 of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 is amended—(1) in subsection (a) (2), by striking out ", of which guaranties of credit union investment shall not exceed $1,250,000"; and (2) in subsection (a) (4), by striking out "December 31, 1977" and inserting in lieu thereof "September 30, 1981[.]" |

|

OPIC Amendments Act of 1981 |

October 16, 1981 |

September 30, 1985 Sec. 5... (b)(1) Section 235(a)(5) of such Act, as redesignated by subsection (a)(2)(A) of this section, is amended by striking out "September 30, 1981" and inserting in lieu thereof "September 30, 1985[.]" |

|

OPIC Amendments Act of 1985 |

December 23, 1985 |

September 30, 1988 Section 235(a)(5) (22 U.S.C. 2195(a)5)) is amended by striking out "1985" and inserting in lieu thereof "1988[.]" |

|

OPIC Amendments Act of 1988 |

October 1, 1988 |

September 30, 1992 P.L. 100-461: Sec. 555...That title I of H.R. 5263 as passed by the House of Representatives on September 20, 1988, is hereby enacted into law: H.R. 5263 (100th Congress, 2nd Session): Sec 107. Extending Issuing Authority. Section 235(a)(6) of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 (22 U.S.C. 2195(a)(6)) is amended by striking out "1988" and inserting in lieu thereof "1992[.]" |

|

Jobs Through Exports Act of 1992 |

October 28, 1992 |

September 30, 1994 SEC. 104. ...(3) TERMINATION OF AUTHORITY.—The authority of subsections (a) and (b) of section 234 shall continue until September 30,1994[.] |

|

Jobs Through Trade Expansion Act of 1994 (P.L. 103-392) |

October 22, 1994 |

September 30, 1996 SEC. 103. EXTENDING ISSUING AUTHORITY. Section 235(a)(3) of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 (22 U.S.C. 2195(a)(3)) is amended by striking "1994" and inserting "1996[.]" |

|

Omnibus Consolidated Appropriations Act, 1997 (P.L. 104-208) |

September 30, 1996 |

September 30, 1997 That section 235(a)(3) of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 (22 U.S.C. 2195(a)(3)) is amended by striking out ''1996'' and inserting in lieu thereof ''1997[.]'' |

|

Continuing Appropriations, 1998 (P.L. 105-46) |

September 30, 1997 |

October 23, 1997 SECTION 101. (a) Such amounts as may be necessary under the authority and conditions provided in the applicable appropriations Act for the fiscal year 1997 for continuing projects or activities including the costs of direct loans and loan guarantees (not otherwise specifically provided for in this joint resolution) which were conducted in the fiscal year 1997 and for which appropriations, funds, or other authority would be available in the following appropriations Acts: ... (6) the Foreign Operations, Export Financing, and Related Programs Appropriations Act, 1998, notwithstanding section 10 of Public Law 91–672 and section 15(a) of the State Department Basic Authorities Act of 1956 ... SEC. 106. Unless otherwise provided for in this joint resolution or in the applicable appropriations Act, appropriations and funds made available and authority granted pursuant to this joint resolution shall be available until: (1) enactment into law of an appropriation for any project or activity provided for in this joint resolution; or (2) the enactment into law of the applicable appropriations Act by both Houses without any provision for such project or activity; or (3) October 23, 1997, whichever first occurs. |

|

Further Continuing Appropriations, 1998 |

P.L. 105-64, October 23, 1997 P.L. 105-69, November 9, 1997 P.L. 105-71, November 10, 1997 P.L. 105-84, November 14, 1997 |

November 26, 1997 (Short-term CRs extended OPIC's authority, ultimately through November 26, 1997.) P.L. 105-84, enacted on November 14, 1997: That section 106(3) of Public Law 105–46 is further amended by striking ''November 14, 1997'' and inserting in lieu thereof ''November 26, 1997[.]' |

|

Foreign Operations, Export Financing, and Related Programs Appropriations Act, 1998 (P.L. 105-118) |

November 26, 1997 |

September 30, 1999 SEC. 581. (a) IN GENERAL.—Section 235(a) of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 (22 U.S.C. 2195(a)) is amended— (1) by striking paragraphs (1) and (2)(A) and inserting the following: ''(1) INSURANCE AND FINANCING.—(A) The maximum contingent liability outstanding at any one time pursuant to insurance issued under section 234(a), and the amount of financing issued under sections 234(b) and (c), shall not exceed in the aggregate $29,000,000,000.''; (2) by redesignating paragraph (3) as paragraph (2); and (3) by amending paragraph (2) (as so redesignated) by striking ''September 30, 1997'' and inserting ''September 30, 1999[.]'' (b) CONFORMING AMENDMENT.—Paragraph (2) of section 235(a) of that Act (22 U.S.C. 2195(a)), as redesignated by subsection (a), is further amended by striking ''(a) and (b)'' and inserting ''(a), (b), and (c)[.]'' |

|

Continuing Appropriation for FY 2000 (P.L. 106-62) |

September 30, 1999 |

October 21, 1999 SEC. 106. Unless otherwise provided for in this joint resolution or in the applicable appropriations Act, appropriations and funds made available and authority granted pursuant to this joint resolution shall be available until: (a) enactment into law of an appropriation for any project or activity provided for in this joint resolution; (b) the enactment into law of the applicable appropriations Act by both Houses without any provision for such project or activity; or (c) October 21, 1999, whichever first occurs. SEC. 117. Notwithstanding section 235(a)(2) of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 (22 U.S.C. 2195(a)(2)), the authority of section 234(a) (b) and (c), of the same Act, shall remain in effect during the period of this joint resolution. |

|

Continuing Appropriation for FY 2000 (various CRs, see "Enacted" column) |

P.L. 106-75, October 21, 1999 P.L. 106-85, October 29, 1999 P.L. 106-88, November 5, 1999 P.L. 106-94, November 10, 1999 P.L. 106-105, November 18, 1999 P.L. 106-106, November 19, 1999 |

December 2, 1999 (Short-term CRs extended authority until December 2, 1999.) P.L. 106-106, enacted on November 19, 1999: Public Law 106–62 is further amended by striking ''November 18, 1999'' in section 106(c) and inserting ''December 2, 1999'', and by striking ''$346,483,754'' in section 119 and inserting ''$755,719,054[.]'. |

|

Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2000 (P.L. 106-113) |

November 29, 1999 |

November 1, 2000 Appendix B: OPIC AUTHORIZATION SEC. 599E. Section 235(a)(2) of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 (22 U.S.C. 2195(a)(2)) is amended by striking ''1999'' and inserting ''November 1, 2000[.]'. |

|

Export Enhancement Act of 1999 |

December 9, 1999 |

September 30, 2003 SEC. 2. OPIC ISSUING AUTHORITY. Section 235(a)(2) of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 (22 U.S.C. 2195a)(3)) is amended by striking "1999" and inserting "2003[.]" |

|

Continuing Appropriations for FY 2004 (P.L. 108-84) |

September 30, 2003 |

October 31, 2003 SEC. 107. Unless otherwise provided for in this joint resolution or in the applicable appropriations Act, appropriations and funds made available and authority granted pursuant to this joint resolution shall be available until (a) enactment into law of an appropriation for any project or activity provided for in this joint resolution, or (b) the enactment into law of the applicable appropriations Act by both Houses without any provision for such project or activity, or (c) October 31, 2003, whichever first occurs.... ...SEC. 115. Notwithstanding section 235(a)(2) of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 (22 U.S.C. 2195(a)(2)), the authority of subsections (a) through (c) of section 234 of such Act, shall remain in effect through the date specified in section 107(c) of this joint resolution[.] |

|

Continuing Appropriations for FY 2004 (various CRs, see "Enacted" column) |

P.L. 108-104, October 31, 2003 P.L. 108-107, November 7, 2003 P.L. 108-135, November 22, 2003 |

January 31, 2004 (In three additional CRs, authority was extended successively to January 31, 2004.) P.L. 108-135, enacted on November 22, 2003: That Public Law 108–84 is amended by striking the date specified in section 107(c) and inserting ''January 31, 2004[.]'' |

|

OPIC Amendments Act of 2003 |

December 3, 2003 |

September 30, 2007a SEC. 2. ISSUING AUTHORITY. Section 235(a)(2) of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 (22 U.S.C. 2195(a)(2)) is amended by striking "November 1, 2000"' and inserting "2007[.]" |

Source: CRS, based on searches of Congress.gov, ProQuest Congressional, and Title 22 of the U.S. Code.

Notes: To identify the legislation in this table, CRS examined the notes of Title 22 sections 2194 and 2195 of the U.S. Code, and searched Congress.gov and ProQuest Congressional for additional pieces of legislation extending OPIC's authority. While all efforts were made to ensure the comprehensiveness of this list, the presence of any gaps in authorization legislation should not be regarded as determinative of OPIC's authorization status.

a. The Amendment Notes of the 2000 edition of the U.S. Code (1/6/2003), for section 2195(a)(2) of Title 22 explain: "Subsec. (a)(2). Pub. L. 106–158, which directed the amendment of par. (2) by substituting "2003" for "1999" could not be executed because "1999" did not appear in text subsequent to amendment by Pub. L. 106–113. See below ...Pub. L. 106–113, which directed amendment of par. (2) by substituting "November 1, 2000" for "1999", was executed by making the substitution for "September 30, 1999", to reflect the probable intent of Congress."

|

Development Finance Institutions |

Sponsor |

|

Bilateral |

|

|

Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC) |

United States |

|

Association of European Development Finance Institutions (EDFI) |

|

|

Belgian Investment Company for Developing Countries (BIO); Belgian Corporation for International Investment (SBI-BMI) |

Belgium |

|

CDC Group* |

United Kingdom |

|

Compañía Española de Financiación del Desarrollo (COFIDES) |

Spain |

|

Entrepreneurial Development Cooperation (DEG) |

Germany |

|

Finnish Fund for Industrial Cooperation Ltd. (FINNFUND) |

Finland |

|

The Investment Fund for Developing Countries (IFU) |

Denmark |

|

Netherlands Development Finance Company (FMO) |

Netherlands |

|

Norwegian Investment Fund for Developing Countries (Norfund) |

Norway |

|

Oesterreichische Entwicklungbank AG (OoEB; The Development Bank of Austria) |

Austria |

|

Société de Promotion et de Participation pour la Coopération Economique (Proparco) |

France |

|

Swiss Investment Fund for Emerging Markets (SIFEM) |

Switzerland |

|

Società Italiana per le Imprese all'Estero (SIMEST) |

Italy |

|

Sociedade para o Financiamento do Desenvolvimento (SOFID) |

Portugal |

|

Swedfund International AB (Swedfund) |

Sweden |

|

Japanese Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC) |

Japan |

|

Export-Import Bank of China; China Export and Credit Insurance Corporation (Sinosure); China Development Bank (CDB) |

China |

|

Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES) |

Brazil |

|

Export Credit Guarantee Corporation of India (ECGC) |

India |

|

Regional |

|

|

African Development Bank (AfDB); Asian Development Bank (ADB); European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD); Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) |

|

|

Multilateral |

|

|

International Finance Corporation (IFC)**; Multilateral Investment Guaranty Agency (MIGA)** |

|

Source: CRS compilation from International Finance Corporation (IFC), International Finance Institutions and Development: Private Sector, 2011; Christian Kingombe, Isabella Massa and Dirk Willem te Velde, Comparing Development Institutions Literature Review, Overseas Development Institute, January 20, 2011; Association of European Development Finance Institutions (EDFI) publications; and various other DFI publications and annual reports.

Notes: * CDC (United Kingdom) formerly was Colonial Development Corporation, then Commonwealth Development Corporation.

** IFC and MIGA are both part of The World Bank Group.