Introduction

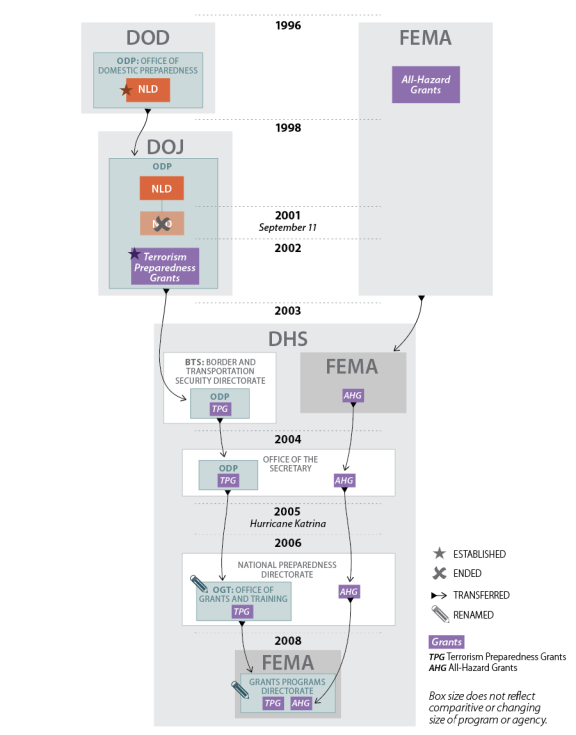

Congress has enacted legislation and appropriated grant funding to states and localities for homeland security purposes since 1996.1 One of the first programs to provide this type of funding was the Nunn-Lugar-Domenici Program which was established by Congress in the 1996 Department of Defense Reauthorization Act2 and provided assistance to over 150 cities for biological, chemical, and nuclear security. Providing homeland security assistance to states and localities was arguably spurred by the 1993 bombing of the World Trade Center in New York City and the 1995 bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah federal building in Oklahoma City. Following the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, Congress increased focus on state and local homeland security assistance by, among other things, establishing the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and authorizing DHS to administer federal homeland security grant programs.3 This report focuses on the department's homeland security assistance programs for states and localities, but not the department as a whole.4

With the increase of international and domestic terrorist threats and attacks against the United States following the end of the Cold War, and the termination of the old federal civil defense programs, a number of policy questions arose regarding homeland security assistance programs. The majority of these questions have not been completely addressed, even though Congress has debated and enacted legislation that provides homeland security assistance to states and localities since 1996.

The number and purpose of programs, their administration, and funding levels have evolved over the past 20 years. These programs are intended to enhance and maintain state, local, and nonfederal or nongovernmental entity5 homeland security and emergency management capabilities. These grants were administered by numerous offices and agencies and include the

- Office for Domestic Preparedness which was within the Border and Transportation Security Directorate;

- Office for State and Local Government Coordination and Preparedness which was within the Office of the Secretary;

- Office for Grants and Training which was within the Preparedness Directorate; and

- Grants Programs Directorate within the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).

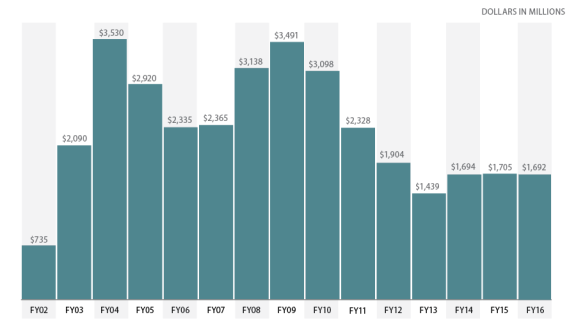

Over the course of DHS's administration of the preparedness grant programs, the programs' eligible uses also evolved. Initially, DHS preparedness grant program funding could not be used for state and local law enforcement personnel costs such as overtime, but for the past couple of fiscal years, states and localities can fund law enforcement personnel overtime using this money. This guidance change is a combination of DHS's evaluation of risks and threats and at the request of states and localities. The 'high-water' amount of funding peaked in approximately FY2009, with the following fiscal years seeing a slight but consistent decline in program funding that may be attributed to the policy concept of only needing to maintain previously established state and local homeland security capabilities.

This report provides a brief summary of the development of DHS's role in providing homeland security assistance, a summary of the current homeland security programs managed by DHS, and a discussion of the following policy questions: (1) the purpose and number of programs; (2) the use of homeland security assistance program funding; and (3) the funding amounts for the programs.

|

List of Pertinent Acronyms 1. Nunn-Lugar-Domenici Program (NLD) 2. Office for Domestic Preparedness (ODP) 3. Grants Program Directorate (GPD) 4. Emergency Management Performance Grant Program (EMPG) 5. Homeland Security Grant Program (HSGP) 6. State Homeland Security Grant Program (SHSP) 7. Urban Area Security Initiative (UASI) 8. Operation Stonegarden (OPSG) 9. Intercity Bus Security Grant Program (IBSGP) 10. Intercity Passenger Rail Security—Amtrak Grant Program (IPR) 11. Port Security Grant Program (PSGP) 12. Tribal Homeland Security Grant Program (THSGP) 13. Transit Security Grant Program (TSGP) |

Historical Development of Federal Assistance

In 1996, Congress enacted the Defense Against Weapons of Mass Destruction Act (known as the Nunn-Lugar-Domenici Act). This law, among other things, established the Nunn-Lugar-Domenici Program (NLD) and was intended to provide financial assistance to major U.S. metropolitan statistical areas. This assistance, with the Oklahoma City bombing being the primary catalyst, was focused on assisting first responders to prepare for, prevent, and respond to terrorist attacks involving weapons of mass destruction.6 Initially, the Department of Defense (DOD) was responsible for administering NLD, but, in 1998, NLD was transferred to the Department of Justice (DOJ) which then established the Office of Domestic Preparedness (ODP) to administer NLD, and other activities that enhanced state and local emergency response capabilities.7 Initially, forty cities had received funding by 1998, and by 2001, 120 cities had received assistance. The NLD ended in 2001 with a total of 157 cities receiving training and funding for personal protective equipment.8

ODP was transferred to DHS with enactment of the Homeland Security Act of 2002.9 Initially, ODP and its terrorism preparedness programs were administered by the Border and Transportation Security Directorate, and all-hazard preparedness programs were in the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). ODP and all preparedness assistance programs were transferred to the Office of the Secretary in DHS in 2004. After investigations into the problematic response to Hurricane Katrina, the programs were transferred to the National Preparedness Directorate. Currently all programs and activities are administered by the Grants Program Directorate (GPD) within FEMA. Figure 1 provides a graphical representation of the historical development of the administration of federal homeland security assistance from 1996 to present.

|

Figure 1. Historical Development of Homeland Security Assistance |

|

|

Source: CRS analysis of the evolution of DHS grants administration. |

Since the establishment of DHS, the department has not only been responsible for preparing for and responding to terrorist attacks, it is also the lead agency for preparing for, responding to, and recovering from any accidental man-made or natural disasters. P.L. 110-53, Implementing Recommendations of the 9/11 Commission Act of 2007, authorized a number of the DHS grants and mandated some of their allocation methodologies. This legislation was a result of numerous years of debate on how DHS should allocate homeland security assistance funding to states, the District of Columbia, and U.S. insular areas.10

Summary of Grant Programs

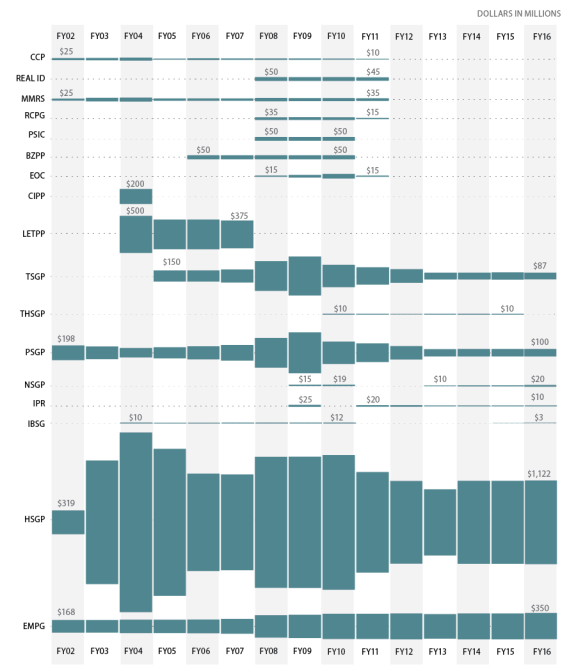

In FY2003, DHS administered 8 homeland security grant programs, and there are now 10 in FY2016. DHS administered as many as 15 programs in FY2010. The following section summarizes the 10 programs and activities that are currently administered by DHS. This report uses DHS documents to summarize the programs. This report is not intended to provide in-depth information on these grants. For detailed information on individual grant programs, see the cited sources.

Preparedness (Non-Disaster) Grant Programs

All 10 programs administered by FEMA's Grants Program Directorate (GPD) are preparedness (non-disaster) grants. These programs specifically "provide state and local governments with preparedness program funding in the form of non-disaster grants to enhance the capacity of state and local emergency responders to prevent, respond to, and recover from a weapons of mass destruction terrorism incident involving chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, explosive devices, and cyber-attacks."11

Emergency Management Performance Grant Program (EMPG)12

EMPG is intended to provide federal funds to states to assist state, local, territorial, and tribal governments in preparing for all hazards. These funds are to provide a system of emergency preparedness for the "protection of life and property in the United States from hazards and to vest responsibility for emergency preparedness jointly in the Federal Government, states, and their political subdivisions."13 The EMPG's priority is to support the implementation of the National Preparedness System.14

Homeland Security Grant Program (HSGP)15

HSGP supports state and local activities to prevent terrorism and other catastrophic events and to prepare for threats and hazards that pose the "greatest" risk to the nation's security. HSGP is comprised of three grant programs—State Homeland Security Grant Program (SHSP), Urban Area Security Initiative (UASI), and Operation Stonegarden (OPSG).16

SHSP

SHSP assists state, tribal, and local governments with preparedness activities that address high-priority preparedness gaps across all preparedness core capabilities where a nexus to terrorism exists. Jurisdictions need core capabilities that are "flexible" and determine how to apply resources to prepare to respond to specific threats to specific jurisdictions. Communities need preparedness capabilities to prevent, protect against, mitigate, respond to, and recover from threats and hazards that pose the greatest risk.17All federal investments are based on capability targets and gaps identified during the Threat and Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment (THIRA) process, and assessed in the State Preparedness Report (SPR).18 THIRA is a four-step common risk assessment process that assists individuals, businesses, faith-based organizations, nonprofit groups, schools and academia, and all levels of government to understand its risks and estimate capability requirements.19 SPR is a self-assessment of a jurisdiction's current capability levels against the capability targets identified in its THIRA.20

UASI

UASI assists high-threat, high-density urban areas to build and sustain the capabilities necessary to prevent, protect against, mitigate, respond to, and recover from terrorist attacks.21 Federal UASI investments are based on UASI recipients' THIRA.

OPSG

OPSG supports enhanced cooperation and coordination among Customs and Border Protection (CBP), U.S. Border Patrol (USBP), and local, tribal, territorial, state, and federal law enforcement agencies. OPSG provides funding for investments in joint efforts to secure the nation's borders along routes of ingress from international borders to include travel corridors in states bordering Mexico and Canada, as well as states and territories with international water borders.22

Intercity Bus Security Grant Program (IBSGP)23

IBSGP supports transportation infrastructure security activities that strengthen against risks associated with potential terrorist attacks. Federal funding for IBSGP supports critical infrastructure hardening and other physical security enhancements to intercity bus operators serving the nation's highest-risk metropolitan areas.24

Intercity Passenger Rail Security—Amtrak Grant Program (IPR)25

IPR supports the nation's rail system by providing funds for activities that prevent, protect against, mitigate, respond to, and recover from terrorist attacks. Examples of this support are building and sustaining emergency management capabilities, protection of high-risk and high-consequence underwater and underground rail assets, and emergency preparedness drills and exercises.26

Nonprofit Security Grant Program (NSGP)27

NSGP provides funding support for target hardening and other physical security enhancements to non-profit organizations that are at high risk of a terrorist attack and located within one of the FY2015 UASI-designated urban areas. The program intends to promote emergency preparedness coordination and collaboration activities between public and private community representatives as well as state and local government agencies.28

Port Security Grant Program (PSGP)29

PSGP supports efforts to build and sustain National Preparedness Goal30 core capabilities across the Goal's mission areas, with specific focus on addressing the nation's maritime ports' security needs. The PSGP's objectives are

- enhancing maritime domain awareness;

- enhancing Improvised Explosive Device (IED) and Chemical, Biological, Radiological, Nuclear, and Explosive (CBRNE) prevention, protection, response, and supporting recovery capabilities within the maritime domain;

- enhancing cybersecurity capabilities;

- supporting maritime security risk mitigation projects;

- supporting maritime preparedness training and exercises; and

- implementing the Transportation Worker Identification Credential (TWIC).31

Tribal Homeland Security Grant Program (THSGP)32

THSGP funds are intended to increase U.S. native tribal abilities to prevent, prepare for, protect against, and respond to acts of terrorism. Some objectives of THSGP include advancing a whole-community approach to security and emergency preparedness, and strengthening cooperation and coordination among local, regional, and state preparedness partners.33

Transit Security Grant Program (TSGP)34

TSGP directly support transportation infrastructure security activities. The program provides funds to owners and operators of transit systems—including intra-city bus, commuter bus, ferries, and all forms of passenger rail—to protect critical surface transportation infrastructure and the traveling public from acts of terrorism and to increase the resilience of transit infrastructure.35

Eligible Grant Recipients

Each of the grant programs summarized above has different eligible recipients and processes that determine allocations. The following table provides information on these 10 grant programs.

Table 1.Eligible Recipients and Allocation Process, of FY2016 Homeland Security Assistance, by Program

|

Program |

Eligible Recipients |

Allocation Process |

|

EMPG |

states, DC, Puerto Rico, and U.S. insular areas |

allocation formula mandated by Congress |

|

HSGP |

||

|

SHSP |

states, DC, Puerto Rico, and U.S. insular areas |

allocation formula mandated by Congress |

|

UASI |

high-threat, high-risk urban areas |

determined by DHS through a risk assessment |

|

OPSG |

international land and water border states, localities, and tribes |

determined by U.S. Customs and Border Protection sector-specific border risk methodology |

|

IBSG |

owners and operators of fixed-route intercity and charter buses serving UASI jurisdictions |

determined by DHS through a risk assessment |

|

IPR |

The National Passenger Railroad Corporation (Amtrak) |

determined by DHS through a risk assessment of Amtrak routes/stations in UASI jurisdictions |

|

NSGP |

501(c)(3) nonprofit organizations |

determined by DHS Secretary through a risk assessment of nonprofits in UASI jurisdictions |

|

PSGP |

owners and operators of port facilities and ferries, and state and local government entities responsible for port security |

competitive review process by DHS |

|

THSGP |

"Indian Tribe" defined by 6 U.S.C. §601(4) |

determined by DHS through a risk assessment and peer review |

|

TSGP |

state, local, and privately owned transit agencies in UASI jurisdictions |

determined by DHS through a risk assessment and competitive process |

Source: CRS review of U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Federal Emergency Management Agency, "Preparedness (Non-Disaster) Grants," available at https://www.fema.gov/preparedness-non-disaster-grants.

Overview of Grant Life Cycle and Appropriations Data

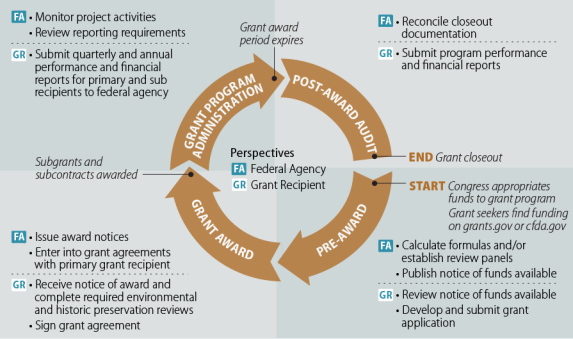

Generally, DHS grants follow the grant life cycle shown below in Figure 2. The life cycle of a federal grant traditionally includes four stages: pre-award, grant award, grant program administration, and post-award audit. Figures 3 and 4 provide information on appropriations for DHS grant programs from FY2002 to FY2016.

|

|

Source: CRS Report R42769, Federal Grants-in-Aid Administration: A Primer, by Natalie Keegan. |

This grant life cycle is how most federal grants are administered, applied for, and allocated. DHS grants follow this grant life cycle.

Issues for Congress

More than 15 years after the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, and approximately 13 years since the establishment of DHS, debate continues on policy questions related to homeland security assistance for states and localities. Some of these questions arguably have been addressed in legislation, such as the statute that modified the distribution of funding to states and localities (P.L. 110-53). Some may contend there is a need for the Congress to conduct further oversight hearings and legislate on policy issues related to DHS assistance to states and localities. These potential issues include (1) the purpose and number of assistance programs; (2) the use of grant funding; and (3) the funding level for the grant programs. The following analysis of these issues provides background for this policy discussion.

Purpose and Number of Assistance Programs

Generally, each grant program has a range of eligible activities. When Congress authorizes a federal grant program, the eligible activities may be broad or specific depending on the statutory language in the grant authorization. When grant funds are distributed through a competitive process, the administering federal agency officials exercise discretion in the selection of grant projects to be awarded funding within the range of eligible activities set forth by Congress.36

Some may argue the purpose and number of DHS grant programs have not been sufficiently addressed. Specifically, should DHS provide more all-hazards assistance versus terrorism-focused assistance? Does the number of individual grant programs result in coordination challenges and deficient preparedness at the state and local level? Would program consolidation improve domestic security? Finally, does the purpose and number of assistance programs affect the administration of the grants?

An all-hazards assistance program allows recipients to obligate and fund activities to prepare for, respond to, and recover from almost any emergency regardless of type or reason, which includes man-made (accidental or intentional) and natural disasters. EMPG is an example of an all-hazards assistance program. Terrorism preparedness-focused programs allow recipients to obligate and fund activities to prepare for, respond to, and recover from terrorist incidents. SHSG is an example of a terrorism preparedness-focused program.

The majority of disasters and emergencies that have occurred since September 11, 2001, have been natural disasters from everyday floods and tornadoes, to major incidents such as Hurricane Katrina. However, the majority of homeland security assistance funding to states and localities has been appropriated to programs dedicated to preparing for and responding to terrorist attacks. A DHS fact sheet regarding Homeland Security Presidential Directive 837 states that federal preparedness assistance is intended primarily to support state and local efforts to build capacity to address major (or catastrophic) events, especially terrorism.38

In July 2005, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) stated that emergency response capabilities for terrorism, as well as man-made and natural disasters, are similar for response and recovery activities, but differ for preparedness.39 The similarity is associated with first responder actions following a disaster that are focused on immediately saving lives and mitigating the effects of the disaster. Preparing for a hurricane, or any natural disaster, by comparison is markedly different than preparing for a terrorist attack. Preparing for or preventing a terrorist attack includes such activities as installing security barriers and conducting counter-intelligence, whereas preparing for a natural disaster involves a different set of functions such as planning for evacuations or stockpiling equipment, food, and water. GAO stated that legislation and presidential directives related to emergencies and disasters following the September 2001 terrorist attacks emphasize terrorism preparedness.40 One way potentially to address the issue of all-hazards versus terrorism preparedness is to consolidate these grants into a single block grant program. If a block grant were authorized and appropriated by Congress, states and localities may be allowed to identify the individual threats and risks that are unique to their location.

An example of a consolidation of DHS grants into a single block grant is when the Obama Administration first proposed the National Preparedness Grant Program (NPGP) in its FY2013 budget request to Congress, and again in FY2014. Congress denied the request both times. Congress expressed concern that the NPGP had not been authorized by Congress, lacked sufficient detail regarding the implementation of the program, and lacked sufficient stakeholder participation in the development of the proposal.41

The Administration proposed the NPGP once again in FY2015 budget request. The Administration indicated that its latest proposal included adjustments that responded to congressional concerns. The committee-reported bills and P.L. 114-4 opposed the Administration's grant reform proposals, and continued a general provision barring the establishment of the National Preparedness Grant Program or similar structures without explicit congressional authorization.42

Evaluation of Funding Use

Another issue Congress may wish to address is how effectively DHS's assistance to states and localities is being spent. One way to review the use of program funding is to evaluate state and local jurisdictions' use of DHS's assistance. When DHS announces annual state and locality homeland security grant allocations, grant recipients submit implementation plans that identify how these allocations are to be obligated. However, the question remains whether or not the grant funding has been used in an effective way to enhance the nation's homeland security. There are some ways that grant recipients audit their fund use.

Primary grant recipients are required to conduct an annual audit of federal grant funds and to submit the findings of the audit to the federal government. The Single Audit Act (P.L. 98-502, as amended) provides one of the government's primary grant oversight mechanisms.43 The act requires nonfederal entities that expend more than $500,000 in a year in federal awards to be audited for that year. Auditors evaluate the grantee's financial statements, test the agency's internal controls, and identify material non-compliance with the terms of the grant agreement or other federal regulation or law. Under the Single Audit Act, primary grant recipients were able to conduct a single audit that would fulfill the audit requirements for all federal grants each fiscal year. All audits performed under the act are submitted to the Federal Audit Clearinghouse, a database maintained by the Census Bureau, and may be viewed at no charge by the public.

Federal grant recipients who expend $500,000 or more in federal grant funds during a single fiscal year are required to submit an audit to the Federal Audit Clearinghouse (FAC) on an annual basis.44 The audit must detail the federal grant expenditures. It is difficult to compare the data in the FAC to other grant databases because audits are based on expenditures during the grant recipient fiscal year, which may differ from the federal government fiscal year.45 These audits however do not necessarily determine if grants assist recipients in meeting national preparedness goals.

DHS grants to states and localities are intended for grant recipients to meet national preparedness goals. Grant recipients' use of these grants is evaluated; however, this evaluation has been an evolving process. In December 2003, President George W. Bush issued Homeland Security Presidential Directive–846 (HSPD–8), which required the newly established DHS Secretary to coordinate federal preparedness activities and coordinate support for state and local first responder preparedness. HSPD–8 directed DHS to establish measurable readiness priorities and targets. Following Hurricane Katrina, the Post-Katrina Emergency Management Reform Act (PKEMRA) was enacted in October 2006. PKEMRA required FEMA to develop specific, flexible, and measurable guidelines to define risk-based target preparedness capabilities and to establish preparedness priorities that reflected an appropriate balance between the relative risks and resources associated with all-hazards.47

Almost a year later in September 2007, DHS published the National Preparedness Guidelines.48 The guidelines are to "organize and synchronize" national efforts to

- strengthen national preparedness;

- guide national investments in national preparedness;

- incorporate lessons learned;

- facilitate a capability-based and risk-based investment planning process; and

- establish readiness metrics to measure progress, and a system for assessing the nation's overall preparedness capability to respond to major events, especially those involving acts of terrorism.49

In March 2011, President Barack Obama issued Presidential Policy Directive–8 (PPD–8), which directed the development of a national preparedness goal50 and the identification of the core capabilities necessary for preparedness. PPD–8 replaced HSPD–8.51

In 2012, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) conducted a review of SHSP, UASI, PSGP, and TSGP. GAO's major findings included that these DHS grant programs had overlap and other factors that increased the risk of duplication among the grant programs.52 Specifically, GAO found that each of these grant programs funded similar projects such as training, planning, equipment, and exercises. Additionally, GAO found that even though the programs target different constituencies, such as states and counties, urban areas, and ports or transit entities, there was overlap across recipients.53 Finally, GAO found that DHS made grant award decisions using varying levels of information (based on specific grant application processes) which contributed to the risk of funding duplicative homeland security projects.54 One final question remains, and that is whether or not these grants are effective in assisting states and localities in meeting national preparedness goals.

Funding Amounts

Annual federal support, through the appropriations process, for these homeland security grant programs is another issue Congress may want to examine considering the limited financial resources available to the federal government. Specifically, is there a need for the continuation of federal support for these programs, or should Congress reduce or eliminate funding? In the past 13 years, Congress has appropriated approximately $33 billion for state and local homeland security assistance. Since the establishment of DHS in 2003, Congress appropriated a high total of funding of $3.5 billion in FY2004, and the lowest appropriated amount was $1.4 billion in FY2013. This data is presented in Figures 3 and 4.

|

Figure 3. Total DHS Assistance for States and Localities, FY2002-FY2016 |

|

|

Source: CRS analysis of total annual appropriations for DHS grants. |

|

Figure 4. Individual DHS Assistance for States and Localities, FY2002-FY2016 |

|

Table 2. FY2002-FY2016 Appropriations for Homeland Security Assistance Programs

(dollars in millions)

|

FY02 |

FY03 |

FY04 |

FY05 |

FY06 |

FY07 |

FY08 |

FY09 |

FY10 |

FY11 |

FY12 |

FY13 |

FY14 |

FY15 |

FY16 |

|

|

EMPG |

168 |

170 |

180 |

180 |

185 |

200 |

300 |

315 |

340 |

340 |

350 |

332 |

350 |

350 |

350 |

|

HSGP |

319 |

1,670 |

2,425 |

1,985 |

1,315 |

1,295 |

1,770 |

1,773 |

1,818 |

1,358 |

1,118 |

893 |

1,121 |

1,122 |

1,122 |

|

SHSP |

316 |

1,870 |

1,700 |

1,100 |

550 |

525 |

950 |

890a |

890d |

579 |

- |

346 |

466 |

467 |

467 |

|

UASI |

3 |

800 |

725 |

885 |

765 |

770 |

820 |

823b |

868e |

724 |

- |

500 |

600 |

600 |

600 |

|

OPSG |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

60c |

60f |

55 |

50 |

47 |

55 |

55 |

55 |

|

IBSG |

- |

- |

10 |

10 |

10 |

12 |

12 |

12 |

12 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

3 |

3 |

|

IPR |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

25 |

- |

20 |

20 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

|

NSGP |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

15 |

19 |

- |

- |

10 |

13 |

13 |

20 |

|

PSGP |

198 |

170 |

125 |

150 |

175 |

210 |

400 |

550 |

300 |

250 |

180 |

97 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

|

THSGP |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

10 |

10 |

6 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

|

|

TSGP |

- |

- |

- |

150 |

150 |

175 |

400 |

525 |

300 |

230 |

180 |

87 |

90 |

97 |

87 |

|

LETPP |

- |

- |

500 |

400 |

400 |

375 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

CIPPp |

- |

- |

200 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

EOC |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

15 |

35 |

60 |

15 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

BZPP |

- |

- |

- |

- |

50 |

50 |

50 |

50 |

50 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

PSIC |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

50 |

50 |

50 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

RCPG |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

35 |

35 |

35 |

15 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

MMRS |

25 |

50 |

50 |

30 |

30 |

33 |

41 |

41 |

41 |

35 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

REAL ID |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

50 |

50 |

50 |

45 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

CCP |

25 |

30 |

40 |

15 |

20 |

15 |

15 |

15 |

13 |

10 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

Total |

735 |

2,090 |

3,530 |

2,920 |

2,335 |

2,365 |

3,138 |

3,491 |

3,098 |

2,328 |

1,904 |

1,439 |

1,694 |

1,705 |

1,692 |

Source: CRS analysis of annual DHS appropriations from FY2002 to FY2016.

Some might argue that since over $33 billion has been appropriated and allocated for state and local homeland security, jurisdictions should have met their homeland security needs. This point of view would lead one to assume that Congress should reduce funding to a level that ensures states and localities are able to maintain their homeland security capabilities, but not fund new homeland security projects. Additionally, some may argue that states and localities should assume more responsibility for funding their homeland security projects, and that the federal government should reduce overall funding. Whether this approach maintains the status quo may depend on a given state's or locality's financial conditions.

Another argument for maintaining present funding levels is the ever-changing terrorism threat and the constant threat of natural and accidental man-made disasters. As one homeland security threat (natural or man-made) is identified and met, other threats develop and require new homeland security capabilities or processes. Some may even argue that funding amounts should be increased due to any potential increase in natural disasters and their costs.