In 1964, the Wilderness Act1 established a national system of congressionally designated areas to be preserved in a wilderness condition: "where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain."2 The National Wilderness Preservation System (the Wilderness System) was originally created with 9 million acres of Forest Service lands. Congress has since added approximately 100 million more acres to the Wilderness System (see Table 1) among some 608.9 million acres of land managed by the federal land management agencies—the Forest Service in the Department of Agriculture, and the National Park Service (NPS), Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), and Bureau of Land Management (BLM) in the Department of the Interior.3 Federal agencies, Members of Congress, and interest groups have recommended additional lands for inclusion in the Wilderness System. Furthermore, at the direction of Congress, agencies have studied, or are studying, the wilderness potential of their lands. This report provides a brief history of wilderness, describes what wilderness is, identifies permitted and prohibited uses in wilderness areas, and provides data on the 109.9 million acres of designated wilderness areas as of April 15, 2016. For information on current wilderness legislation, see CRS Report R41610, Wilderness: Issues and Legislation.

History of Wilderness

As the United States was formed, the federal government acquired 1.8 billion acres of land through purchases, treaties, and other agreements. Initial federal policy was generally to transfer land to states and private ownership, but Congress also provided for reserving certain lands for federal purposes. Over time, Congress has reserved or withdrawn increasing acreage for national parks, national forests, wildlife refuges, etc. The general policy of land disposal was formally changed to a policy of retaining the remaining lands in the Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976 (FLPMA).4

The early national forests were managed for conservation—protecting and developing the lands for sustained use. It did not take long for some Forest Service leaders to recognize the need to preserve some areas in a natural state. Acting at its own discretion, and at the behest of an employee named Aldo Leopold, the Forest Service created the first wilderness area in the Gila National Forest in New Mexico in 1924. In the succeeding decades, the agency's system of wilderness, wild, and primitive areas grew to 14.6 million acres. However, in the 1950s, increasing timber harvests and recreational use of the national forests led to public concerns about the permanence of this purely administrative system. The Forest Service had relied on its administrative authority in making wilderness designations, but there was no law to prevent a future change to those designations.

In response, Congress enacted the Wilderness Act in 1964. The act described the attributes and characteristics of wilderness, and it prohibited or restricted certain activities in wilderness areas to preserve and protect the designated areas, while permitting other activities to occur. The act reserves to Congress the authority to designate areas as part of the National Wilderness Preservation System.

The Wilderness System began with the 9.1 million acres of national forest lands that had been identified administratively as wilderness areas or wild areas. The Wilderness Act directed the Secretary of Agriculture to review the agency's 5.5 million acres of primitive areas, and the Secretary of the Interior to evaluate the wilderness potential of National Park System and National Wildlife Refuge System lands. The Secretaries were to report their recommendations to the President and to Congress within 10 years (i.e., by 1974). Separate recommendations were made for each area, and many areas recommended for wilderness were later designated, although some of the recommendations are still pending. In 1976, FLPMA directed the Secretary of the Interior to conduct a similar review of the public lands administered by BLM within 15 years (i.e., by 1991). BLM submitted its recommendations to the President, and presidential recommendations were submitted to Congress (see "BLM Wilderness Review and Wilderness Study Areas").

The 90th Congress began expanding the Wilderness System in 1968, as shown in Table 1. Five laws were enacted, creating five new wilderness areas with 792,750 acres in four states. Wilderness designations generally increased in each succeeding Congress, rising to a peak of 60.8 million acres designated during the 96th Congress (1979-1980), the largest amount designated by any Congress. This figure included the largest single designation of 56.4 million acres of wilderness through the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act.5 The 98th Congress enacted more wilderness laws (21) and designated more acres (8.5 million acres in 21 states) outside of Alaska than any Congress since the Wilderness System was created. The 112th Congress was the first Congress to designate no additional wilderness acres.

Including the Wilderness Act, Congress has enacted more than 100 laws designating new wilderness areas or adding to existing ones, as shown in Table 1. To date, the 114th Congress has designated three new wilderness areas. The Wilderness System now contains 765 wilderness areas, with approximately 109.9 million acres in 44 states and Puerto Rico, managed by the four federal land-management agencies, as shown in Table 2. The agencies have recommended that additional lands be added to the Wilderness System; these lands are generally managed to protect their wilderness character while Congress considers adding them to the Wilderness System (see "Wilderness Review, Study, and Release"). The agencies are studying additional lands to determine if these lands should be added to the Wilderness System. However, comprehensive data on the lands recommended and being reviewed for wilderness potential are not available.

|

Congress |

Number of Lawsa |

Number of States |

Number of New Areas (Additions)b |

Acres Designatedc |

||||

|

88th |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

89th |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

90th |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

91st |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

92nd |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

93rd |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

94th |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

95th |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

96th |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

97th |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

98th |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

99th |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

100th |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

101st |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

102nd |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

103rd |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

104th |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

105th |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

106th |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

107th |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

108th |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

109th |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

110th |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

111th |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

112th |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

113th |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

114th |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Total |

|

|

|

|

Source: Created by the Congressional Research Service (CRS).

a. Excludes laws with minor boundary and acreage adjustments (less than 10 acres of net change).

b. The first number indicates the number of new wilderness areas; the number in parentheses indicates the number of additions to existing wilderness areas.

c. This total reports the acreage as designated and differs from the total of the column because of acreage revisions.

d. This figure includes 56.4 million acres that were designated wilderness through the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA: P.L. 96-487).

What Is Wilderness?

The Wilderness Act described wilderness as an area of generally undisturbed federal land. Specifically, Section 2(c) defined wilderness as

A wilderness, in contrast with those areas where man and his works dominate the landscape, is hereby recognized as an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain. An area of wilderness is further defined to mean ... an area of undeveloped Federal land retaining its primeval character and influence, without permanent improvements or human habitation, which is protected and managed so as to preserve its natural conditions and which (1) generally appears to have been affected primarily by the forces of nature, with the imprint of man's work substantially unnoticeable; (2) has outstanding opportunities for solitude or a primitive and unconfined type of recreation; (3) has at least five thousand acres of land or is of sufficient size as to make practicable its preservation and use in an unimpaired condition; and (4) may also contain ecological, geological, or other features of scientific, educational, scenic, or historical value.6

This definition provides some general guidelines for determining which areas should, or should not, be designated wilderness, but the law contains no specific criteria. The phrases "untrammeled by man," "retaining its primeval character," and "man's work substantially unnoticeable" are far from precise. Even the numerical standard (5,000 acres) is not absolute; smaller areas can be designated if they can be protected, and the smallest wilderness area—Wisconsin Islands Wilderness in the Green Bay National Wildlife Refuge—is only 2 acres.

These imprecise criteria stem in part from differing perceptions of what constitutes wilderness. To some, wilderness is an area where there is absolutely no sign of human presence: no traffic can be heard (including aircraft); no roads, structures, or litter can be seen. To others, sleeping in a camper in a 400-site campground in Yellowstone National Park is a wilderness experience. Complicating these differing perceptions is the wide range of ability to "get away from it all" in various settings. In a densely wooded area, isolation might be measured in yards; in mountainous or desert terrain, human developments can sometimes be seen for miles.

Section 2 of the Wilderness Act also identified the purposes of wilderness. Specifically, Section 2(a) stated that the act's purpose was to create wilderness lands "administered for the use and enjoyment of the American people in such manner as will leave them unimpaired for future use and enjoyment as wilderness, and so as to provide for the protection of these areas, the preservation of their wilderness character, and for the gathering and dissemination of information regarding their use and enjoyment as wilderness."7 These criteria also contain degrees of imprecision, sometimes leading to different perceptions about how to manage wilderness. Thus, there are contrasting views about what constitutes wilderness and how wilderness should be managed.

In an attempt to accommodate contrasting views of wilderness, the Wilderness Act provided certain exemptions and delayed implementation of restrictions for wilderness areas, as will be discussed below. At times, Congress has also responded to the conflicting demands of various interest groups by allowing additional exemptions for certain uses (especially for existing activities) in particular wilderness designations. The subsequent wilderness statutes have not designated wilderness areas by amending the Wilderness Act. Instead, they are independent statutes. Although nearly all of these statutes direct management in accordance with the Wilderness Act, many also provide unique management guidance for their designated areas. Ultimately, wilderness areas are whatever Congress designates as wilderness, regardless of developments or activities that some might argue conflict with the act's definition of wilderness.

Statutory Management Provisions

The Wilderness Act and subsequent wilderness laws contain several provisions addressing management of wilderness areas. These laws designate wilderness areas as part of and within existing units of federal land, and the management provisions applicable to those units of federal land, particularly those governing management direction and restricting activities, also apply. For example, hunting is prohibited in most NPS units but not on most Forest Service or BLM lands. Thus, hunting would be prohibited for the wilderness areas in those NPS units but would be permitted in Forest Service or BLM wilderness areas, absent specific statutory language.

In addition to the management requirements applicable to the underlying federal land, most of the subsequent wilderness statutes direct management of the designated areas in accordance with or consistent with the Wilderness Act, although some management provisions have been expanded or clarified.

- State Fish and Wildlife Jurisdiction and Responsibilities. The Wilderness Act explicitly directed that wilderness designations had no effect on state jurisdiction or responsibilities over fish and wildlife jurisdiction (Section 4(d)(8)).8 Comparable language, sometimes only referring to state jurisdiction (not responsibilities) has been included in many of the wilderness statutes.

- Jurisdiction and Authorities of Other Agencies. Several wilderness statutes have directed that other agencies' specific authorities, jurisdiction, and related activities be allowed to continue. For example, some wilderness statutes specify that the wilderness designation has no effect on law enforcement, generally, or on U.S.-Mexico border relations, drug interdiction, or military training.

- Water Rights. Wilderness statutes have provided different directions concerning federal reserved water rights associated with the designated wilderness areas. The Wilderness Act expressly states that it does not claim or deny a reserved water right (Section 4(d)(7)),9 whereas some wilderness statutes have expressly reserved, or denied, claims to federal water rights. Wilderness statutes frequently provide that state law dictates regulation of water allocation and use.

- Buffer Zones. The Wilderness Act is silent on the issue of buffer zones around wilderness areas to protect the designated areas. However, in response to concern that designating wilderness areas would restrict management of adjoining federal lands, language in many subsequent wilderness bills has prohibited buffer zones that would limit uses and activities on federal lands around the wilderness areas.

- Land and Rights Acquisition and Future Designations. The Wilderness Act authorizes the acquisition of land within designated wilderness areas (called inholdings), including through donation or exchange for other federal land (Section 5(a-c)),10 subject to appropriations. Congress has also enacted several wilderness statutes with intended or potential wilderness that are within or adjoining designated wilderness areas. These areas are to become wilderness when certain conditions have been met, such as acquisition, as specified in the statute.

- Wilderness Study, Review, and Release. Many of the wilderness statutes have directed the agencies to review the wilderness potential of certain lands and present recommendations regarding wilderness designations to the President and to Congress. (See the "Wilderness Review, Study, and Release" section, below.) However, the Wilderness Act and most of the initial statutory wilderness review provisions were silent on the management of the areas during and after the review, leading to concerns about how to manage areas not recommended for wilderness designation. A legislative provision, called release language, was developed to address this concern. Release language provides direction on the timing of future wilderness review and of the management of areas not designated as wilderness until the next review.

The Wilderness Act, and subsequent statutes, authorized some uses to continue, particularly if the uses were authorized at the time of designation. For example, the Wilderness Act specifically directs that "the grazing of livestock, where established prior to the effective date of this Act, shall be permitted to continue subject to such reasonable regulations as are deemed necessary by the Secretary of Agriculture" (Section 4(d)(4)(2)).11 Congress expanded on this language by providing additional guidance on continuing livestock grazing at historic levels in designated wilderness areas (H. Rept. 96-617, which accompanied P.L. 96-560, and Appendix A—Grazing Guidelines—in H.Rept. 101-405, which accompanied P.L. 101-628). Many of the subsequent wilderness statutes also expressly directed continued livestock grazing in conformance with the Wilderness Act and the committee reports.

The Wilderness Act extended the mining and mineral leasing laws for wilderness areas in national forests for 20 years, through 1983. Until midnight on December 31, 1983, new mining claims and mineral leases were permitted for those wilderness areas and exploration and development were authorized, "subject, however, to such reasonable regulations governing ingress and egress as may be prescribed by the Secretary of Agriculture."12 On January 1, 1984, the Wilderness Act withdrew the specified national forest wilderness areas from all forms of appropriation under the mining laws. Some subsequent wilderness statutes have specifically withdrawn the designated areas from availability under the mining and mineral laws, whereas others have directed continued mineral development and extraction or otherwise allowed historical use of an existing mine to continue within designated areas.

Prohibited Uses

The Wilderness Act, directly and by cross-reference in virtually all subsequent wilderness statutes, generally prohibits commercial activities; motorized uses; and roads, structures, and facilities in designated wilderness areas. Specifically, Section 4(c) states:

Except as specifically provided for in this Act, and subject to existing private rights, there shall be no commercial enterprise and no permanent road within any wilderness area designated by this Act and, except as necessary to meet minimum requirements for the administration of the area for the purpose of this Act (including measures required in emergencies involving the health and safety of persons within the area), there shall be no temporary road, no use of motor vehicles, motorized equipment or motorboats, no landing of aircraft, no other form of mechanical transport, and no structure or installation within any such area.

Thus, most businesses and commercial resource development—such as timber harvesting—are prohibited, except "for activities which are proper for realizing the recreational or other wilderness purposes of the areas" (§4(d)(6)). The use of motorized or mechanized equipment—such as cars, trucks, off-road vehicles, bicycles, aircraft, or motorboats—is also prohibited, except in emergencies and specified circumstances. Human infrastructure—such as roads, buildings, dams and pipelines—is likewise prohibited in wilderness areas. However, the Wilderness Act is silent on the treatment of infrastructure in place at the time of the designation, although many of the wilderness statutes do address it through "Nonconforming Permitted Uses" provisions. Many wilderness statutes have authorized closing certain wilderness areas (or parts thereof) to public access. In addition, many statutes have withdrawn the designated areas from the public land disposal laws13 and the mining and mineral leasing and disposal laws, although valid existing rights are not terminated and can be developed under reasonable regulations.

Nonconforming Permitted Uses

The Wilderness Act and many subsequent wilderness statutes have allowed various nonconforming uses and conditions, especially if such uses were in place at the time of designation. Motorized access has generally been permitted for management requirements and emergencies; for nonfederal inholdings; and for fire, insect, and disease control. Continued motorized access and livestock grazing have also generally been permitted where they had been occurring prior to the area's designation as wilderness, as discussed above. In addition, construction, operations, and maintenance—and associated motorized access—have been permitted for water infrastructure and for other infrastructure in many instances. Motorized access for state agencies for fish and wildlife management activities has sometimes been explicitly allowed. Several statutes have expressly permitted low-level military overflights of wilderness areas, although the Wilderness Act does not prohibit overflights. Access for minerals activities has been authorized in some specific areas and for valid existing rights. Finally, several statutes have allowed access for other specific activities, such as access to cemeteries within designated areas or for tribal activities.

Wilderness Review, Study, and Release

Congress directed the four land-management agencies to review the wilderness potential of their lands and make recommendations regarding the lands' suitability for wilderness designation. Congress acted upon many of those recommendations, by either designating lands as wilderness or by releasing lands from further wilderness consideration. However, some recommendations remain pending. Questions and discussions persist over the protection and management of these areas, which some believe should be designated as wilderness and others believe should be available for development. This debate has been particularly controversial for Forest Service inventoried roadless areas and BLM wilderness study areas.

Forest Service Wilderness Reviews and Inventoried Roadless Areas

The Wilderness Act directed the Secretary of Agriculture to review the wilderness potential of primitive areas identified by the Forest Service and to make wilderness recommendations for those lands within 10 years (i.e., by 1974). In 1970, the Forest Service expanded its review of potential wilderness areas to include lands that had not been previously identified as primitive areas. This Roadless Area Review and Evaluation (RARE) was conducted under the newly enacted National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA).14 The Forest Service issued the final environmental impact statement in 1973 and was sued for not properly following the NEPA process in identifying potential wilderness areas. It chose not to present the recommendations to Congress.

In 1977, the Forest Service began a second review (RARE II) of the 62 million acres of national forest roadless areas, to accelerate part of the land-management planning process mandated by the Forest and Rangeland Renewable Resources Planning Act of 1974 and the National Forest Management Act of 1976 (NFMA).15 The RARE II final environmental impact statement was issued in January 1979, recommending more than 15 million acres (24% of the study area) for addition to the Wilderness System. In addition, nearly 11 million acres (17%) were to be studied further in the ongoing Forest Service planning process under NFMA. The remaining 36 million acres (58% of the RARE II area) were to be available for other uses—such as logging, energy and mineral developments, and motorized recreation—that might be incompatible with preserving wilderness characteristics. In April 1979, President Jimmy Carter presented the recommendations to Congress with minor changes.

In 1980, the state of California successfully challenged the Forest Service RARE II recommendations for 44 areas allocated to non-wilderness uses, with the court decision substantially upheld on appeal in 1982.16 The Reagan Administration responded in 1983 by directing a reevaluation of all RARE II recommendations. Tensions between Congress and the Administration, and among interest groups, led to a particularly intense debate during the 98th Congress (1983-1984). Many statewide wilderness laws were subsequently enacted, each containing language releasing some lands in that state from potential wilderness designations (release language).

The completion of RARE II and subsequent enactment of bills designating national forest wilderness areas has not ended the debate, and the Forest Service has other directives to consider the wilderness values or the undisturbed condition of national forest lands (e.g., NFMA). Further, there are extensive roadless areas within the National Forest System that have not been designated wilderness. To address the management and protection of the 58.5 million acres of inventoried roadless areas (primarily RARE II areas not designated as wilderness),17 the Clinton Administration developed regulations that would keep all roadless areas free from most development (the Roadless Rule).18 More than a decade of litigation followed, with the Clinton Administration's rule being enjoined twice and the Bush Administration promulgating a rule that also was enjoined. The courts deciding the cases upheld the Clinton Administration's rule, and in October 2012, the Supreme Court refused to review the issue.19 Currently, under the Clinton policy, road construction, reconstruction, and timber harvesting are prohibited on most of the inventoried roadless areas within the National Forest System, with some exceptions.20

BLM Wilderness Review and Wilderness Study Areas

Congress directed BLM to consider wilderness as a use of its public lands in the 1976 enactment of FLPMA. FLPMA required BLM to make an inventory of roadless areas greater than 5,000 acres and to recommend the suitability for designation of those areas to the President within 15 years of October 21, 1976, and the President then had two years to submit wilderness recommendations to Congress. BLM presented its recommendations by October 21, 1991, and Presidents George H. W. Bush and William Clinton submitted wilderness recommendations to Congress. Although these areas have been reviewed and Congress has enacted several statutes designating BLM wilderness areas, many of the wilderness recommendations for BLM lands remain pending. There are two continuing issues for potential BLM wilderness: protection of the wilderness study areas and whether BLM has a continuing obligation under FLPMA to conduct wilderness reviews.

Protection of BLM Wilderness Study Areas

From 1977 through 1979, BLM identified suitable wilderness study areas (WSAs) from roadless areas identified in its initial resource inventory under FLPMA Section 201. Section 603(c) of FLPMA directs the agency to manage those lands "until Congress has determined otherwise … in a manner so as not to impair the suitability of such areas for preservation as wilderness." Thus, BLM must protect the WSAs as if they were wilderness until Congress enacts legislation that releases BLM from that responsibility. This responsibility is sometimes referred to as a non-impairment obligation or standard.

WSAs have been subject to litigation challenging BLM's protection. In the early 2000s, BLM was sued for not adequately preventing impairment of WSAs from increased off-road vehicle use. In Norton v. Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the non-impairment obligation was not enforceable by court challenge.21 The Court held that although WSA protection was mandatory, it was a broad programmatic duty and not a discrete agency obligation. The Court also concluded that the relevant FLPMA land use plans (which indicated that WSAs would be monitored) constituted only management goals that might be modified by agency priorities and available funding and were not a basis for enforcement under the Administrative Procedure Act. Therefore, it appears that although BLM actions that would harm WSAs could be enjoined, as with any agency enforcement obligation,22 forcing BLM to take protective action would be difficult at best.

BLM Reviews for Wilderness Potential

Despite BLM's continuing obligation under FLPMA Section 201 to identify the resources on its lands, giving priority to areas of critical environmental concern,23 it is unclear whether BLM is required to review its lands specifically for wilderness potential after expiration of the reviews required by Section 603.24 In contrast to the Forest Service, which must revise its land and resource management plans at least every 15 years, BLM is not required to revise its plans on a specified cycle; rather, it must revise its land and resource management plans "when appropriate." Furthermore, while NFMA includes wilderness in the planning process, both directly and by reference to the Multiple Use-Sustained Yield Act of 1960, FLPMA is silent on wilderness in the definitions of multiple use and sustained yield and in the guidance for the BLM planning process. Thus, future BLM wilderness reviews are less certain than future Forest Service wilderness reviews.

DOI Wilderness Policy Changes

With each Administration, DOI has changed its policy regarding how it administers areas with wilderness potential. In September 2003, then-DOI secretary Gale Norton settled litigation challenging a 1996 policy identifying large amounts of wilderness-suitable lands.25 Following the settlement, the BLM assistant director issued guidance (known as Instruction Memorandum 2003-274) prohibiting further reviews and limiting the term wilderness study areas and the non-impairment standard to areas already designated for the original Section 603 reviews of the 1970s and 1980s.26 The guidance advised, in part, that because the Section 603 authority expired, "there is no general legal authority for the BLM to designate lands as WSAs for management pursuant to the non-impairment standard prescribed by Congress for Section 603 WSAs."27

On December 22, 2010, then-DOI secretary Ken Salazar issued Order No. 3310, known as the Wild Lands Policy, addressing how BLM would manage wilderness.28 This order indirectly modified the 2003 wilderness guidance without actually overturning the direction (or even acknowledging it). The order relied on the authority in FLPMA Section 201 to inventory lands with wilderness characteristics that are "outside of the areas designated as Wilderness Study Areas and that are pending before Congress" and designated these lands as "Wild Lands." It also directed BLM to consider the wilderness characteristics in land use plans and project decisions, "avoiding impairment of such wilderness characteristics" unless alternative management is deemed appropriate. Whereas Instruction Memorandum 2003-274 indicated that, except for extant Section 603 WSAs, the non-impairment standard did not apply, Order No. 3310 appeared to require an affirmative decision that impairment is appropriate in a Section 201 wilderness resource area. Otherwise, under Order No. 3310, impairment must be avoided. After Congress withheld funding, Secretary Salazar revoked the order in June 2011 and stated that BLM would not designate any wild lands.29 Despite the order being formally revoked, Congress has continued to withhold funding in annual appropriations acts.30

Data on Wilderness Designations as of April 15, 2016

The wilderness statistics presented in Table 2 are the most recent acreage estimates for wilderness areas that have been designated by Congress as compiled by the agencies. Acreages are estimates, since few (if any) of the areas have been precisely surveyed. In addition, the agencies have recommended areas for addition to the National Wilderness Preservation System, and continue to review the wilderness potential of other lands under their jurisdiction, both of congressionally designated wilderness study areas and under congressionally directed land management planning efforts. However, statistics on acreage in pending recommendations and being studied, particularly in the planning efforts, are unavailable.

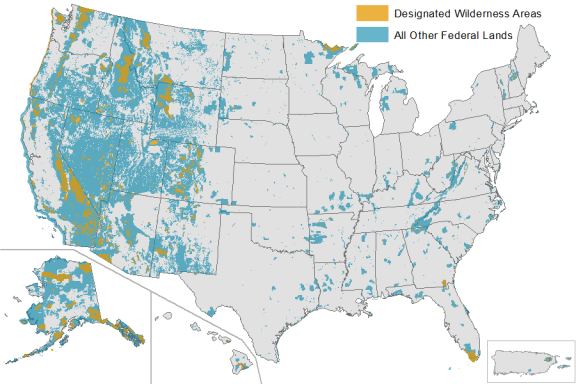

As of April 15, 2016, Congress has designated 109.9 million acres of federal land in units of the National Wilderness Preservation System, as shown in Table 2 and Figure 1. Wilderness areas have been designated in 44 states plus Puerto Rico; only Connecticut, Delaware, Iowa, Kansas, Maryland, and Rhode Island have no federal lands designated as wilderness. Figure 2 shows the regional distribution of lands designated as wilderness. Just over half (52%) of this land—57.4 million acres—is in Alaska, and includes most of the wilderness areas managed by NPS (75%), FWS (90%), and FS (16%).31 California has the next-largest wilderness acreage, with 15.0 million acres designated in the state. However, Washington is the state with the largest percentage of federal land designated wilderness, with the 4.5 million acres of wilderness accounting for 38% of the federal land within the state. NPS manages the most wilderness acreage (43.9 million acres, 40% of the Wilderness System), followed by the Forest Service, which manages 36.6 million acres (33%). FWS manages 20.7 million acres (19%), and BLM manages the least wilderness acreage, 8.7 million acres (8%).

|

Figure 2. Regional Distribution of Wilderness Designations, by Acreage |

|

|

|

Source: CRS. Note: The western states are Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington, Wyoming, and Hawaii. The eastern states include the other continental states and Puerto Rico. |

Table 2. Federal Designated Wilderness Acreage, by State and by Agency

(in acres and percentage of agency/federal land)

|

USDA Forest |

National Park |

Fish and Wildlife Service |

Bureau of Land Management |

Total Designated Area |

Share of Wilderness System |

||||||

|

Alabama |

42,219 |

6% |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0% |

42,219 |

6% |

<1% |

|

Alaska |

5,743,827 |

26% |

32,979,406 |

63% |

18,692,615 |

24% |

0 |

0% |

57,415,848 |

26% |

52% |

|

Arizona |

1,327,878 |

12% |

444,055 |

17% |

1,343,444 |

80% |

1,396,966 |

11% |

4,512,343 |

16% |

4% |

|

Arkansas |

115,665 |

4% |

34,933 |

36% |

2,144 |

1% |

0 |

0% |

152,742 |

5% |

<1% |

|

California |

5,099,471 |

25% |

6,011,041 |

79% |

9,172 |

3% |

3,845,156 |

25% |

14,964,682 |

34% |

14% |

|

Colorado |

3,177,258 |

22% |

350,674 |

53% |

2,560 |

1% |

205,814 |

2% |

3,735,054 |

16% |

3% |

|

Connecticut |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0* |

0 |

0% |

0% |

|

Delaware |

0 |

0* |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0* |

0 |

0% |

0% |

|

Florida |

73,835 |

6% |

1,296,500 |

53% |

51,252 |

18% |

0 |

0% |

1,421,587 |

36% |

1% |

|

Georgia |

116,303 |

13% |

9,886 |

25% |

362,107 |

75% |

0 |

0* |

488,316 |

35% |

<1% |

|

Hawaii |

0 |

0* |

155,509 |

43% |

0 |

0* |

0 |

0* |

155,509 |

24% |

<1% |

|

Idaho |

4,210,144 |

21% |

43,243 |

8% |

0 |

0% |

517,362 |

4% |

4,770,749 |

15% |

4% |

|

Illinois |

28,062 |

9% |

0 |

0% |

4,050 |

5% |

0 |

0* |

32,112 |

8% |

<1% |

|

Indiana |

12,472 |

6% |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0* |

12,472 |

5% |

<1% |

|

Iowa |

0 |

0* |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0* |

0 |

0% |

0% |

|

Kansas |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0* |

0 |

0% |

0% |

|

Kentucky |

17,187 |

2% |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0* |

17,187 |

2% |

<1% |

|

Louisiana |

8,701 |

1% |

0 |

0% |

8,346 |

1% |

0 |

0% |

17,047 |

1% |

<1% |

|

Maine |

11,236 |

21% |

0 |

0% |

7,392 |

11% |

0 |

0* |

18,628 |

10% |

<1% |

|

Maryland |

0 |

0* |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0% |

0% |

|

Massachusetts |

0 |

0* |

0 |

0% |

3,244 |

14% |

0 |

0* |

3,244 |

6% |

<1% |

|

Michigan |

89,675 |

3% |

176,315 |

28% |

25,309 |

22% |

0 |

0* |

291,298 |

8% |

<1% |

|

Minnesota |

814,441 |

29% |

0 |

0% |

6,180 |

1% |

0 |

0% |

820,621 |

23% |

1% |

|

Mississippi |

6,026 |

1% |

4,630 |

4% |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0% |

10,656 |

1% |

<1% |

|

Missouri |

64,184 |

4% |

0 |

0% |

7,730 |

13% |

0 |

0* |

71,914 |

4% |

<1% |

|

Montana |

3,431,960 |

20% |

0 |

0% |

64,535 |

10% |

6,347 |

0% |

3,502,842 |

13% |

3% |

|

Nebraska |

7,802 |

2% |

0 |

0% |

4,635 |

3% |

0 |

0% |

12,437 |

2% |

<1% |

|

Nevada |

1,131,197 |

20% |

236,789 |

30% |

0 |

0% |

2,055,681 |

4% |

3,423,667 |

6% |

3% |

|

New Hampshire |

138,405 |

18% |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0* |

138,405 |

17% |

<1% |

|

New Jersey |

0 |

0* |

0 |

0% |

10,341 |

14% |

0 |

0* |

10,341 |

10% |

0% |

|

New Mexico |

1,428,995 |

15% |

56,392 |

12% |

40,048 |

12% |

170,163 |

1% |

1,695,598 |

7% |

2% |

|

New York |

0 |

0% |

1,381 |

4% |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0* |

1,381 |

2% |

<1% |

|

North Carolina |

102,719 |

8% |

0 |

0% |

8,785 |

2% |

0 |

0* |

111,504 |

5% |

<1% |

|

North Dakota |

0 |

0% |

29,920 |

42% |

9,732 |

2% |

0 |

0% |

39,652 |

2% |

<1% |

|

Ohio |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0% |

77 |

1% |

0 |

0* |

77 |

0% |

<1% |

|

Oklahoma |

15,470 |

4% |

0 |

0% |

8,570 |

8% |

0 |

0% |

24,040 |

5% |

<1% |

|

Oregon |

2,228,969 |

14% |

0 |

0% |

940 |

0% |

246,953 |

2% |

2,476,862 |

8% |

2% |

|

Pennsylvania |

9,005 |

2% |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0* |

9,005 |

2% |

<1% |

|

Rhode Island |

0 |

0* |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0* |

0 |

0% |

0% |

|

Puerto Rico |

10,254 |

36% |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0* |

10,254 |

0% |

<1% |

|

South Carolina |

16,751 |

3% |

21,700 |

68% |

29,000 |

22% |

0 |

0* |

67,451 |

8% |

<1% |

|

South Dakota |

13,548 |

1% |

64,144 |

43% |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0% |

77,692 |

3% |

<1% |

|

Tennessee |

66,563 |

9% |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0* |

66,563 |

6% |

<1% |

|

Texas |

38,317 |

5% |

46,850 |

4% |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0% |

85,167 |

3% |

<1% |

|

Utah |

772,949 |

9% |

124,406 |

6% |

0 |

0% |

260,356 |

1% |

1,157,711 |

3% |

1% |

|

Vermont |

100,872 |

25% |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0* |

100,872 |

22% |

<1% |

|

Virginia |

137,085 |

8% |

79,579 |

26% |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0% |

216,664 |

10% |

<1% |

|

Washington |

2,734,788 |

29% |

1,743,100 |

95% |

805 |

0% |

7,140 |

2% |

4,485,833 |

38% |

4% |

|

West Virginia |

119,311 |

11% |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0* |

119,311 |

11% |

<1% |

|

Wisconsin |

46,438 |

3% |

33,500 |

54% |

29 |

0% |

0 |

0% |

79,967 |

4% |

<1% |

|

Wyoming |

3,067,678 |

33% |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0% |

3,067,678 |

10% |

3% |

|

U.S. Total |

36,577,660 |

19% |

43,942,562 |

55% |

20,703,042 |

23% |

8,711,938 |

4% |

109,935,202 |

18% |

100% |

Sources: Forest Service data: Forest Service, Land Areas Report—As of Sept. 30, 2015, Tables 4 and 7, at http://www.fs.fed.us/land/staff/lar/LAR2015index.html. BLM data: BLM, Public Land Statistics—As of Sept. 30, 2014, Tables 1-4 and 5-4, at http://www.blm.gov/public_land_statistics/index.html. NPS data provided via personal correspondence with NPS, 04/2016. FWS data provided via personal correspondence with FWS, 04/2016.

Note: *Indicates that the agency owns no land within the state. Unless otherwise noted, data is current as of September 30, 2015.