Escalating U.S. Tariffs: Affected Trade

Changes from August 16, 2019 to September 12, 2019

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

The trade practices of U.S. trading partners and the U.S. trade deficit are a focus of the Trump Administration. Citing these and other concernsconcerns, the President has imposed tariff increases under three U.S. laws:

- (1) Section 201 of the Trade Act of 1974 on U.S. imports of washing machines and solar products;

- (2) Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 on U.S. imports of steel and aluminum, and potentially motor vehicles/parts and titanium sponge (the President decided not to impose tariffs on uranium imports, after an investigation); and

- (3) Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 on U.S. imports from China.

In May 2019, in response to concerns over immigration, the President also proposed an additional 5% tariff on imports from Mexico under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), but subsequently suspended the proposed tariffs indefinitely citing an agreement reached with Mexico. For a timeline of recent actions, see CRS Insight IN10943, Escalating U.S. Tariffs: Timeline. The Administration has stated that it is using existing and proposed tariffs for a range of purposes, including as leverage for broader trade negotiations with affected trading partners, such as JapanChina, Japan, and the European Union (EU), and, as noted, to influence Mexico's immigration policies.

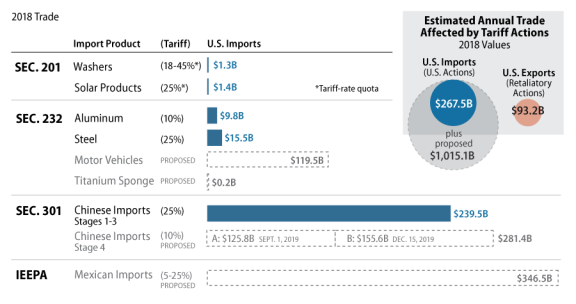

The multiple tariff increases applied to date, ranging from 10% to 45%, affect approximately 1015% of U.S. annual imports. This amounts to $267.5393.3 billion of imports using 2018 annual data, but it should be noted that; notably, the tariffs went into effect at various times in 2018 and 2019 (Figure 1). Section 301 tariffs on U.S. imports from China account for more than 90% of trade affected by the Administration's tariff actions. While the Administration has taken some steps to reduce the scale of imports affected by the tariffs (i.e., by exempting Canada and Mexico from the steel and aluminum duties and creating processes by which certain products may be excluded), the general trend is an escalation of tariff actions.

In May, the Administration increased additional tariffs to 25% on roughly $250 billion of imports from China and recently announced a 10% tariff will be imposed on the remaining roughly $300 billion of imports from China (with some exceptions) in two separate stages, taking effect onthe spring and summer of 2019, the Administration implemented and proposed a series of additional tariff actions, significantly expanding the share of U.S. trade potentially affected. In August, the Administration announced new Section 301 tariffs of 10% on approximately $300 billion of U.S. imports from China. In response, China announced retaliatory measures on approximately $75 billion of U.S. exports, most of which are additional tariffs on U.S. exports already subject to Chinese retaliation. The Administration countered by proposing to increase all U.S. Section 301 tariffs by 5%: from 25% to 30% on the existing approximately $250 billion of imports subject to stage 1-3 tariffs, to take effect on October 1, 2019 (now delayed until October 15, 2019); and from 10% to 15% on the new stage 4A and 4B tariff lists, effective September 1 and December 15 (Figure 1). In addition, President Trump declared U.S. motor vehicle imports a national security threat, particularly from the EU and Japan, granting him authority to impose tariff increases on such imports. The President also proposed an additional 5% to 25% tariff on all imports from Mexico (now indefinitely suspended). In total, these actions would potentially affect over $1 trillion of U.S. imports, or 40% of the annual total. While tariffs may benefit a limited number of import-competing firms, they also increase costs for downstream users of imported products (e.g., Ford estimates the metal tariffs cost the firm nearly $1 billion) and consumers (e.g., research by economists from the New York Federal Reserve estimates the tariffs in effect in 2018 cost the average household $414, and forecasts that the household cost could grow to $831 with the tariff increases now in place), and may have broader negative effects on the U.S. economy, as well as several policy implications.

|

|

Sources: CRS calculations with data from U.S. Census Bureau sourced through Global Trade Atlas. Notes: Based on annual 2018 import values. Excludes exempted countries. Motor vehicle and parts import figure includes only U.S. imports from the European Union and Japan, which were the focus of the President's proclamation declaring motor vehicle imports a national security threat. Tariff-rate quotas (TRQs) are a form of import restriction in which one tariff applies up to a specific quantity or value of imports and a higher tariff applies above that threshold. |

As tariffs act as a tax on foreign-produced goods, they distort price signals, potentially leading to less efficient consumption and production patterns, which may ultimately reduce U.S. and global economic growth rates. As of August 529, 2019, the United States collected $32.735.9 billion from the additional taxes paid by U.S. importers, according to U.S. Customs and Border Protection. Increasing tariffs also create a general environment of economic uncertainty, potentially dampening business investment and creating a further drag on growth. Economic estimates of the tariffPreliminary research, for example, suggests the increase in trade policy uncertainty may have reduced aggregate U.S. investment by 1% or more in 2018. Estimates of the tariffs' overall economic effects vary, depending on modeling assumptions and the specific set of tariffs considered. Most studies, however, predict declines in GDP growth: the Congressional Budget Office estimated that the tariffs in effect as of December 4, 2018July 25, 2019, would lower U.S. GDP on average through 2029 by roughly 0.1 percentage pointby roughly 0.3 percent by 2020 below a baseline without the tariffs; more recently, the OECD estimated that proposed increases on tariffs from China could further reduce U.S. growth by nearly 0.9 percentage points, including negative effects on investmentconsidering also recently proposed actions, the IMF estimated that the tariffs would reduce global GDP in 2020 by 0.5 percent.

Retaliation amplifies the potential effects of the U.S. tariff measures. Retaliatory tariffs in effect, in response to both Section 232 and Section 301 actions, cover approximately $93.297.5 billion of U.S. annual exports, based on 2018 export data (Table 1). This amount is scheduled to increase to $112.5 billion, if China implements its recently announced plans to impose additional tariffs on December 15 and to reinstate additional tariffs on U.S. cars and auto parts. China, like the United States, however, has also begun granting limited tariff exclusions, lessening somewhat the scale of U.S. exports affected by retaliatory tariff measures. Retaliatory tariffs broaden the scope of U.S. industries potentially harmed, targeting those reliant on export markets and sensitive to price fluctuations, such as agricultural commodities. Some U.S. manufacturers have announced plans to shift production to other countries in order to avoid the tariffs on U.S. exports. Lost market access resulting from the retaliatory tariffs may compound concerns raised by many U.S. exporters that the United States increasingly faces higher tariffs than some competitors in foreign markets as other countries conclude trade liberalization agreements, such as the recently-enacted EU-Japan FTA and the TPP-11 agreement, which include major U.S. trade partners, such as Canada, the EU, Japan, and Mexico. Adverse effects could grow if a tit-for-tat process of retaliation continues and the scale of trade affected increases. China recently announced its intent to take countermeasures against the next round of U.S. Section 301 tariffs. As China has already imposed tariff increases on nearly all its U.S. imports, it could potentially increase tariffs on the products it has already targeted or impose various punitive nontariff measures on U.S. firms operating in China. China also recently allowed its currency to depreciate to an 11-year low, which counters the effects of the tariffs and prompted the Administration to label the country a currency manipulator.

|

Retaliatory Trade Action |

U.S. Exports (millions, 2018) |

Additional Tariff |

Effective Date |

|||||||||||||||

|

Section 232 |

EU |

$2,893 |

10-25% |

June 25, 2018 |

||||||||||||||

|

$2,522 |

15-25% |

Apr. 2, 2018 |

||||||||||||||||

|

$1,771 |

4-70% |

June 21, 2018 |

||||||||||||||||

| a |

$1,427 |

10-50% |

June 16, 2019 |

|||||||||||||||

| b |

$430 |

25-40% |

Aug. 6, 2018 |

|||||||||||||||

|

Total Exports Affected by Retaliation |

$9,043 |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Section 301 |

c |

$12,896 |

25% |

July 6, 2018 |

||||||||||||||

| c |

$11,595 |

25% |

Aug. 23, 2018 |

|||||||||||||||

| ,d |

$59,698 |

5-10%/ |

Sept. 24, 2018/ |

|||||||||||||||

|

Total |

$84,189 |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Overall Total in Effect |

$93,232

|

$25,463

|

5-10%

|

China—Stage 4Be (proposed)

Sept. 1, 2019

|

$41,790

|

5-10%

|

Dec. 15, 2019

|

China—Reinstated Auto Tariffs (proposed)

|

$11,720

|

5-25%

|

Total Exports Affected by Retaliationf

Dec. 15, 2019

|

Total and Proposed Exports Affected by Retaliationf

$90,967

|

Overall Total Exports Affected by Retaliationg

$106,014

|

Overall Total and Proposed Exports Affected by Retaliationg

$97,488

|

Sources$112,535 | |||

Source: CRS calculations based on import data of U.S. trade partner countries sourced from Global Trade Atlas and tariff details from WTO or government notifications.

Notes: Canada and Mexico withdrew their retaliation after the Trump Administration exempted both countries from the Section 232 steel and aluminum duties.

a. India's retaliatory tariffs were initially announced at the WTO in June 2018, with tarifftariffs ranging from 10%-50%, but were repeatedly postponed. India's latest announcement appears to remove 2 of the 30 products from its initial list and may affect retaliatory tariff rates.

b. Russia published its list of retaliatory tariff rates and products on July 6, 2018. The tariffs appear to have gone into effect within 30 days of publication.

c. Export calculation excludes auto tariffs suspended until December 15, 2019. d. China's retaliatory tariffs in response to U.S. stage 3 Section 301 tariffs initially ranged from 5-10%. In response to the Trump Administration's increase of Section 301 stage 3 tariffs to 25% on May 10, China increase its retaliatory tariffs on certain products to 20% and 25%

. e. China's Stage 4 retaliation includes new tariffs on 1,600 products and also increases the tariff rates of nearly 3,450 products that are already subject to retaliatory tariffs. f. Total exports adjusted to account for tariff lines affected by multiple stages of China's retaliation to Section 301 tariffs. g. Total exports adjusted to account for tariff lines affected by China's retaliation to both Section 232 and Section 301 tariffs.Many Members of Congress, U.S. businesses, interest groups, and trade partners, including major allies, have weighed in on the President's actions. While some U.S. stakeholders support the President's use of unilateral trade actions to the extent they result in a more level playing field for U.S. firms, many have raised concerns, including the chairman of the Senate Finance committee, who stated that the President's proposed tariffs on Mexico are a "misuse of presidential tariff authority." Several Members have introduced legislation that would constrain the President's authority (e.g., H.R. 723, S. 287, S. 365, and S. 899), while other Members and the Administration hashave advocated for increasing this authority (e.g., H.R. 764). As it debates the Administration's import restrictions, Congress may consider the following:

- Delegation of Authority. Among these statutes, only Section 201 requires an affirmative finding by an independent agency (the ITC) before the President may restrict imports. Section 232 and Section 301 investigations are undertaken by the Administration, giving the President broad discretion in their use. Are additional congressional checks on such discretion necessary?

- Economic Implications and Escalation. The Administration's tariffs imposed to date cover

1015% of annual U.S. goods imports; proposed tariffs could potentially increase this to 40%. Negative effects of the tariffs may be substantial for individual firms reliant either on imports subject to the U.S. tariffs or exports facing retaliatory measures. The potential drag on economic growth could be significant if tit-for-tat action escalates. What are the Administration's ultimate objectives from the tariff increases and do potential benefits justify potential costs? - International Trading System and U.S. Foreign Relations. While the Administration argues that the imposition of U.S. import restrictions is within its rights under international trade agreement obligations, including at the World Trade Organization (WTO), U.S. trade partners disagree and have initiated dispute proceedings, and begun retaliating. The United States has initiated its own dispute proceedings arguing that retaliatory countermeasures violate trade agreement obligations. What are the risks to the international trading system and to broader U.S. foreign policy goals of continued unilateral action and economic confrontation?