The Violence Against Women Act (VAWA): Historical Overview, Funding, and Reauthorization

Changes from November 19, 2018 to April 23, 2019

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Contents

- Introduction

- Origins of VAWA

- Violence Against Women Act of 1994

- Investigations and Prosecutions

- Grant Programs

- Immigration Provisions

- Other VAWA Requirements

- Office on Violence Against Women

- Categories of Crime Addressed through VAWA

- Domestic Violence

- Intimate Partner Homicide

- Sexual Assault

- Dating Violence

- Stalking

- Federal Programs Authorized by VAWA

- FY2018–FY2019 Appropriations

FY2019FY2020 Appropriations- Past Reauthorizations and Changes to VAWA

- 2000 Reauthorization

- 2005 Reauthorization

- 2013 Reauthorization

- Consolidation of Grant Programs

- VAWA Grant Provisions

- Accountability of Grantees

- Sexual Assault and Rape Kit Backlog

- Trafficking in Persons

- American Indian Tribes

- Battered Nonimmigrants

- Underserved Populations

- Housing

- Institutions of Higher Education (IHEs)

- Other Changes

- Rape Survivor Child Custody Act

- Current Efforts to Reauthorize VAWA

- Improvements to Data Collection

- Tribal Jurisdiction

- New Approaches for Law Enforcement

- Domestic Violence and Federal Prohibition of Possession of Firearms

- Other Changes to VAWA Programs

Figures

Tables

- Table 1. FY2018 and FY2019 Appropriations and Set-Asides for VAWA Programs

- Table A-1. Current VAWA-Authorized Programs Funded Under the Departments of Justice and Health and Human Services

- Table A-2. Unfunded VAWA-Authorized Programs

- Table A-3. Five-Year Funding History for VAWA by Administrative Agency

Appendixes

Summary

The Violence Against Women Act (VAWA; Title IV of P.L. 103-322) was originally enacted in 1994. It addressed congressional concerns about violent crime, and violence against women in particular, in several ways. It allowed for enhanced sentencing of repeat federal sex offenders; mandated restitution to victims of specified federal sex offenses; and authorized grants to state, local, and tribal law enforcement entities to investigate and prosecute violent crimes against women, among other things. VAWA has been reauthorized three times since its original enactment. Most recently, Congress passed and President Obama signed the Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2013 (P.L. 113-4), which reauthorized most VAWA programs through FY2018, among other things.

The fundamental goals of VAWA are to prevent violent crime; respond to the needs of crime victims; learn more about crime; and change public attitudes through a collaborative effort by the criminal justice system, social service agencies, research organizations, schools, public health organizations, and private organizations. The federal government tries to achieve these goals primarily through federal grant programs that provide funding to state, tribal, territorial, and local governments; nonprofit organizations; and universities.

VAWA programs generally address domestic violence, sexual assault, dating violence, and stalking—crimes for which the risk of victimization is highest for women—although some VAWA programs address additional crimes. VAWA grant programs largely address the criminal justice system and community response to these crimes, but certain programs address prevention as well.

The Office on Violence Against Women (OVW) administers the majority of VAWA-authorized programs, while other federal agencies, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Office of Justice Programs (OJP), also manage VAWA programs. Since its creation in 1995 through FY2018, OVW has awarded more than $78 billion in grants and cooperative agreements to state, tribal, and local governments, nonprofit organizations, and universities. In FY2018 alone, $553FY2019, approximately $559 million was appropriated for VAWA-authorized programs administered by OVW, OJP, and CDC. While several extensions of authorization for VAWA were provided through FY2019 continuing appropriations, authorizations for appropriations for all VAWA programs have since expired. However, all VAWA programs funded in FY2018 have been funded in FY2019 (select programs at slightly higher levels), and thus far it appears that the expiration of authorizations has not impacted the continuing operation of VAWA programs. The Administration has requested FY2020 funding for all VAWA-authorized programs funded in FY2019 programs administered by OVW, OJP, and CDC. The House, the Senate, and the Administration have all indicated they intend to fund VAWA programs in FY2019. In FY2019 continuing appropriations (P.L. 115-245), a conference report (H.Rept. 115-952) was filed that provided an extension of authorization for VAWA (specifically, "[a]ny program, authority, or provision, including any pilot program, authorized under the Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2013") through December 7, 2018. Thus far in FY2019, appropriations continued for all VAWA programs funded in FY2018 under P.L. 115-245.

There are several issues that Congress may consider in efforts to reauthorize VAWA. These include, but are not limited to, improvements to data collection on domestic violence and stalking or the rape kit backlog; assessing the implementation and future direction of tribal jurisdiction over non-tribal members, including potentially adding new crimes under VAWA; new approaches for law enforcement in assisting victims; and enforcement of the federal prohibition on firearms for those convicted of a misdemeanor crime of domestic violence and those who are subject to a domestic violence protective order. Congress may also consider further changes to VAWA programs. In the 116th Congress, the House passed the Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2019 (H.R. 1585). Among other things, it would reauthorize funding for VAWA programs and authorize new programs; amend and add definitions used for VAWA programs; amend federal criminal law relating to firearms, custodial rape, and stalking; and expand tribal jurisdiction over certain crimes committed on tribal lands.

Introduction

The Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) was originally enacted in 1994 (P.L. 103-322). It addressed congressional concerns about violent crime, and violence against women in particular, in several ways. Among other things, it allowed for enhanced sentencing of repeat federal sex offenders; mandated restitution to victims of specified federal sex offenses; and authorized grants to state, local, and tribal law enforcement entities to investigate and prosecute violent crimes against women.1

This report provides a brief history of VAWA and an overview of the crimes addressed through the act. It includes brief descriptions of earlier VAWA reauthorizations and a more-detailed description of the most recent reauthorization in 2013. It also briefly addresses reauthorization activity in the 116th Congress. The report concludes with a discussion of VAWA programs and a five-year history of funding from FY2014FY2015 through FY2018FY2019.

Origins of VAWA

The enactment of VAWA was ultimately spurred by decades of growing unease over a rising violent crime rate and a focus on women as crime victims. In the 1960s, the violent crime rate rose fairly steadily—it more than doubled from 1960 (160.9 per 100,000) to 1969 (328.7 per 100,000)2—igniting concern from both the public and the federal government. Adding to this was the concern about violent crimes committed against women. In the 1970s, grassroots organizations began to stress the need for attitudinal change among both the public and the law enforcement community regarding violence against women.3

In the 1970s and 1980s, researchers increased their attention on the issue of violence against women as well. In one study, researchers collected data on family violence and attributed declines in spousal assault to heightened awareness of the issue in men as well as the criminal justice system.4 The public and the criminal justice system were beginning to view family violence as a crime rather than a private family matter.5

In 1984, Congress and President Reagan enacted the Family Violence Prevention and Services Act (FVPSA, P.L. 98-457) to assist states in preventing incidents of family violence and to provide shelter and related assistance to victims and their dependents. While FVPSA authorized programs similar to those discussed in this report and FVPSA reauthorizations subsequently reauthorized programs that were originally created by VAWA, such as the National Domestic Violence Hotline, it is a separate piece of legislation and beyond the scope of this report.6

In 1994, Congress passed and President Clinton signed into law, the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 (P.L. 103-322), which included VAWA as Title IV. The act created an unprecedented number of programs geared toward helping local law enforcement fight violent crime and providing services to victims of violent crime, among other things. In their opening remarks on VAWA in 1994, Senators Barbara Boxer and Joseph Biden highlighted the insufficient response to violence against women by police and prosecutors.7 The shortfalls of legal responses and the need for a change in attitudes toward violence against women were primary reasons cited for the passage of VAWA.8

VAWA has been reauthorized three times since its original enactment. Most recently, Congress passed and President Obama signed the Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2013 (P.L. 113-4), which reauthorized most of the programs under VAWA, among other things. In addition, this VAWA reauthorization amended and authorized appropriations for the Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000, enhanced measures to combat trafficking in persons, and amended VAWA grant purpose areas to include sex trafficking. Moreover, P.L. 113-4 gave American Indian tribes authority to enforce tribal laws pertaining to domestic violence and related crimes against non-tribal members,9 and established a nondiscrimination provision for VAWA grant programs. The reauthorization also included new provisions to address states' rape kit backlogs.

Violence Against Women Act of 1994

The Violence Against Women Act of 1994, among other things, (1) enhanced investigations and prosecutions of sex offenses; (2) provided for a number of grant programs to address the issue of violence against women from a variety of angles, including law enforcement, public and private entities and service providers, and victims of crime; and (3) established immigration provisions for abused aliens. The sections below highlight examples of these VAWA provisions.

Investigations and Prosecutions

As originally enacted, VAWA impacted federal investigations and prosecutions of cases involving violence against women in a number of ways. For instance, it established new offenses and penalties for the violation of a protection order or stalking in which an abuser crossed a state line to injure or harass another, or forced a victim to cross a state line under duress and then physically harmed the victim in the course of a violent crime. It added new provisions to require states, tribes, and territories to enforce protection orders issued by other states, tribes, and territories. VAWA allowed for enhanced sentencing of repeat federal sex offenders, and it also authorized funding for the Attorney General to develop training programs to assist probation and parole officers in working with released sex offenders.

In addition, VAWA established a new requirement for pretrial detention of defendants in federal sex offense or child pornography felony cases. It also modified the Federal Rules of Evidence to include new procedures specifying that, with few exceptions, a victim's past sexual behavior was not admissible in federal criminal and civil cases of sexual misconduct.10 Moreover, VAWA directed the Attorney General to study states' actions to ensure confidentiality between sexual assault or domestic violence victims and their counselors.

VAWA mandated restitution to victims of specified federal sex offenses, particularly sexual abuse, sexual exploitation, and other abuse of children. It also established new provisions such as a civil remedy that allows victims of sexual assault to seek civil penalties from their alleged assailants,11 and a provision that allows rape victims to demand that their alleged assailants be tested for HIV.

Grant Programs

The original VAWA created a number of grant programs for a range of activities, including programs aimed at (1) preventing domestic violence and sexual assault; (2) encouraging collaboration among law enforcement, judicial personnel, and public/private sector providers with respect to services for victims of domestic violence and related crimes; (3) investigating and prosecuting domestic violence and related crimes; (4) encouraging states, tribes, and local governments to treat domestic violence as a serious crime and implement arrest policies; (5) bolstering investigations and prosecutions of domestic violence and child abuse in rural states;12 and (6) preventing crime in public transportation as well as public and national parks.

VAWA created new and reauthorized grants under FVPSA.13 These included grants for youth education on domestic violence and intimate partner violence as well as grants for community intervention and prevention programs. It authorized the grant for the National Domestic Violence Hotline and authorized funding for its operation.14 VAWA also reauthorized funding for battered women's shelters.

VAWA authorized research and education grants for judges and court personnel in federal court circuits to gain a better understanding of the nature and the extent of gender bias in the federal courts. It additionally authorized grants for developing model programs for training of state and tribal judges and personnel on laws on rape, sexual assault, domestic violence, and other crimes of violence motivated by the victim's gender. It also authorized a new grant to be used for assisting state and local governments with entering data on stalking and domestic violence into local, state, and national databases—such as the National Crime Information Center (NCIC) database.

VAWA authorized the expansion of grants under the Public Health Service Act15 to include rape prevention education. Additionally, it expanded the purposes of the Runaway and Homeless Youth Act16 to allow for grant funding to assist youth at risk of or who have been subjected to sexual abuse. VAWA reauthorized the Court-Appointed Special Advocate Program and the Child Abuse Training Programs for Judicial Personnel and Practitioners. It also authorized funding for Grants for Televised Testimony by Victims of Child Abuse.

Immigration Provisions17

VAWA of 1994 addressed immigration-related problems faced by battered aliens.18 It included three provisions related to abused aliens: self-petitioning by abused foreign national spouses and their children, required evidence for demonstrating abuse, and suspension of deportation and cancellation of removal.19 These petitions allowed battered foreign national spouses and their children to essentially substitute a self-petition for lawful status in place of a petition for lawful status that was based on sponsorship by the abusive spouse, clarified the evidence required for joint petition waivers, and established requirements for battered foreign national spouses and children to stay deportation.

Other VAWA Requirements

Beyond the criminal justice improvements, grant programs, and immigration provisions, VAWA included provisions for several other activities, including

- requiring that the U.S. Postal Service take measures to ensure confidentiality of domestic violence shelters' and abused persons' addresses;

- mandating federal research by the Attorney General, National Academy of Sciences, and Secretary of Health and Human Services to increase the government's understanding of violence against women; and

- requesting special studies on campus sexual assault and battered women's syndrome.

Office on Violence Against Women

In 1995, the Office on Violence Against Women (OVW) was administratively created within the Department of Justice (DOJ) to administer grants authorized under VAWA. In 2002, OVW was codified through Title IV of the 21st Century Department of Justice Appropriations Authorization Act (P.L. 107-273).20 Since its creation through FY2018, OVW has awarded more than $78 billion in grants and cooperative agreements to state, tribal, and local governments, nonprofit organizations, and universities.21 While OVW administers the majority of VAWA-authorized grants, other federal agencies, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Office of Justice Programs (OJP), also manage VAWA programs.

Categories of Crime Addressed through VAWA

VAWA programs generally address domestic violence, sexual assault, dating violence, and stalking, although some VAWA programs address additional crimes.22 VAWA grant programs largely address the criminal justice system and community response to these crimes, but certain programs address prevention as well. These crimes involve a wide range of victim demographics, but the risk of victimization is highest for women.23

Public concern over violence against women prompted the original passage and enactment of VAWA. As such, VAWA legislation and programs have historically emphasized women victims. More recently, however, there has been a focus on ensuring that the needs of all victims are met through provisions of VAWA programs.24 Of note, while the title of the act and some headings and general purpose areas refer to women only, most VAWA grant purpose areas are not specific to women.

National victimization data on domestic violence, sexual assault, dating violence, and stalking are available from two surveys, the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) and the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System.25 Offense data26 are available from the Federal Bureau of Investigation's (FBI's) Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Program.27 UCR data differ from victimization data because the UCR data describe crimes that were reported to law enforcement, while victimization data include crimes that might not have been reported to law enforcement. Due to differences in what they are trying to measure, victimization data are not directly comparable to UCR data.28

Domestic Violence

Domestic violence can take many forms, but is often labeled as family violence or intimate partner violence. Under VAWA, domestic violence is generally interpreted as intimate partner violence; it includes felony or misdemeanor crimes committed by spouses or ex-spouses, boyfriends or girlfriends, and ex-boyfriends or ex-girlfriends. Crimes may include sexual assault, simple or aggravated assault, and homicide. As defined in statute for the purposes of VAWA grant programs, domestic violence includes

felony or misdemeanor crimes of violence committed by a current or former spouse or intimate partner of the victim, by a person with whom the victim shares a child in common, by a person who is cohabitating with or has cohabitated with the victim as a spouse or intimate partner, by a person similarly situated to a spouse of the victim under the domestic or family violence laws of the jurisdiction receiving grant monies, or by any other person against an adult or youth victim who is protected from that person's acts under the domestic or family violence laws of the jurisdiction.29

From 1993 to 2016, along with a decline in the overall violent crime rate,302017, the rate of serious intimate partner violence31 victimization30 declined by 70% for females, from 5.7 victimizations per 1,000 females aged 12 and older in 1993 to 1.7 per 1,000 in 20162017; and 87% for males, from 1.5 victimizations per 1,000 males aged 12 and older in 1993 to 0.2 per 1,000 in 2016.322017.31 In 2015, a survey conducted by the CDC included questions about lifetime victimization. The CDC estimates that 21.4% of women and 14.9% of men have experienced severe physical violence3332 by an intimate partner in their lifetime.34

Intimate Partner Homicide

Since peaking in the early 1990s, the violent crime rate (including homicide and intimate partner homicide) has declined.3534 Although it has fluctuated over the last several years, the violent crime rate remains far lower now than it was in the 1990s.3635 In examining the initial decline in the 1990s and early 2000s, researchers studied a range of social factors that may influence homicide rates and suggested possible reasons for the decline in the intimate partner homicide rate.3736 For instance, most intimate partner homicides involve married couples; as such, some researchers suggested the decline in marriage rates among young adults is a contributing factor in the decline in intimate partner homicide rates.3837 Additionally, divorce and separation rates increased. Fewer marriages may result in less exposure to abusive partners, and may suggest that those who do marry are more selective in choosing a partner.39

Overall, homicide is committed largely by males, mostly victimizing other males. In 2017, males made up 84% of all offenders and 78% of all homicide victims; however, 78% of all intimate partner homicide victims were female.4039 From 2003-2014, the CDC found that approximately 55% of female homicides for which circumstances were known were related to intimate partner violence.4140

Sexual Assault

Sexual assault may include the crimes of forcible rape, attempted forcible rape, assault with intent to rape, statutory rape,4241 and other sexual offenses. For VAWA programs, sexual assault is defined as "any nonconsensual sexual act proscribed by Federal, tribal, or State law, including when the victim lacks capacity to consent."4342 Sexual assault is termed as "sexual abuse" and "aggravated sexual abuse" under federal criminal law.4443 Of note, intimate partner violence can, and often does, include sexual assault.45

Until 2012, and for the purposes of its UCR program, the FBI defined forcible rape as "the carnal knowledge of a female forcibly and against her will."4645 In January 2012, the FBI revised its definition of rape, and 2013-2017 rape data4746 rely on the following definition: "penetration, no matter how slight, of the vagina or anus with any body part or object, or oral penetration by a sex organ of another person, without the consent of the victim."4847 The new, more inclusive definition

- includes either male or female victims or offenders,

- includes instances in which the victim is incapable of giving consent because of temporary or permanent mental or physical incapacity, and

- reflects the various forms of sexual penetration understood to be rape.

4948

Both the legacy definition and the current definition exclude statutory rape—nonforcible sexual intercourse with or between individuals, at least one of whom is younger than the age of consent.50

According to UCR data, and applying the revised definition of rape, 135,755 forcible rapes were reported to law enforcement in 2017—a rate of 41.7 per 100,000 people.5150 From 2013-2017, the number of rapes (revised definition) increased by 19.4%, and the rate increased each year, from 35.9 per 100,000 in 2013 to 41.7 per 100,000 in 2017.52

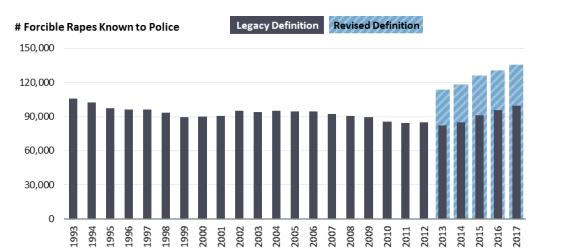

Using the legacy definition, 99,856 forcible rapes were reported to law enforcement in 2017. Since 1990, when 102,555 forcible rapes (previous definition) were reported, the number has fluctuated but has generally declined, though it also has increased each year since 2013 (see Figure 1).

|

Figure 1. Forcible Rapes Known to Police (United States, 1993-2017) |

|

|

Source: CRS presentation of UCR data. These data are available at https://ucr.fbi.gov. Notes: For the legacy and revised definitions of forcible rape, see the text of the report. |

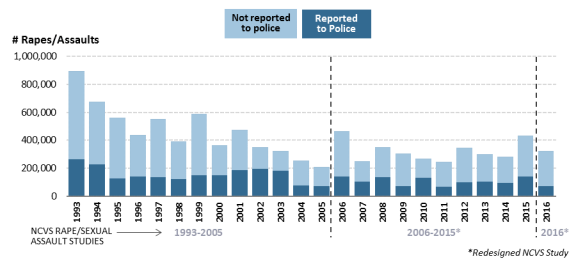

According to statistics from the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS), it is estimated that there were 323,449393,980 sexual assaults (1.24 per 1,000 aged 12 and older) in 20162017—which is more than doublenearly triple the number of forcible rapes reported in the UCR for 2016.532017 UCR.52 As noted, NCVS estimates are not directly comparable to UCR program data because these datavictimizations are self-reported during interviews53 and are not necessarilymay not have been reported to law enforcement. The UCR and NCVS also measure rape and sexual assault differently—among other variations, the NCVS combines rape and sexual assault into one category.54

As shown in Figure 2, and similar to UCR data, NCVS data reflect a decline in sexual assaults since 1993; however, the victimization survey went through a redesign in 2006 and 2016, so data over time should be interpreted with caution.55 Figure 2 demonstrates that a fairly low percentage of rape/sexual assaults are reported to police each year. In 20162017, it is estimated that 2340% of rape or sexual assault incidents were reported to the police—nearly double the percentage that were reported in 2016.56

|

Figure 2. Sexual Assault Victimizations Reported and Not Reported to Police

|

|

|

Source: CRS presentation of estimates from the U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. Estimates generated using the NCVS Victimization Analysis Tool (NVAT) at http://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=nvat, Notes: |

Dating Violence

Under VAWA, dating violence refers to "violence committed by a person who is or has been in a social relationship of a romantic or intimate nature with the victim."57 The relationship between the offender and victim is determined based on the following factors: (1) the length of the relationship, (2) the type of relationship, and (3) the frequency of interaction between the persons involved in the relationship.58

While teenagers are not the only demographic subject to dating violence, data reports on dating violence usually refer to teenagers as the relevant age demographic. According to the CDC's 2017 Youth Risk Behavior Survey, approximately 8.0% of high school students who dated or went out with someone during the 12 months before the survey reported being "hit, slammed into something, or injured with an object or weapon on purpose by someone they were dating or going out with" one or more times in the past year.59 The prevalence of physical dating violence victimization was higher among female students (9.1%) than male students (6.5%).60 The overall percentage of high school students experiencing physical dating violence has declined since the CDC first included the question in its 2013 survey. In 2013, approximately 10.3% of high school students reported being a victim of physical dating violence; in 2015, it was 9.6%; and in 2017, it was 8.0%.61

Stalking

All 50 states, the District of Columbia, and U.S. territories have stalking laws, though they vary in definition.62 Federal law makes it unlawful to travel across state lines63 or use the mail or computer and electronic communication services64 with the intent to kill, injure, harass, or intimidate another person, and as a result, place that person in reasonable fear of death or serious bodily injury or cause substantial emotional distress to that person, a spouse or intimate partner of that person, or a member of that person's family.65

The NCVS Supplemental Victimization Survey (SVS)66 defines stalking as "a course of conduct directed at a specific person that would cause a reasonable person to feel fear."67 The SVS measures these unwanted stalking behaviors:

- making unwanted phone calls;

- sending unsolicited or unwanted letters or emails;

- following or spying on;

- showing up at places without a legitimate reason;

- waiting at places for the victim;

- leaving unwanted items, presents, or flowers; or

- posting information or spreading rumors about the victim on the internet, in a public place, or by word of mouth.

According to the NCVS SVS, an estimated 3.3 million individuals aged 18 and older were victims of stalking in 2006. More females than males were stalked. Also, the percentage of individuals targeted decreased with age; those aged 18-24 experienced the highest incidence of stalking.68

November 2018.

According to the NCVS SVS, an estimated 3.3 million individuals aged 18 and older were victims of stalking in 2006. More females than males were stalked. Also, the percentage of individuals targeted decreased with age; those aged 18-24 experienced the highest incidence of stalking.68

- unwanted phone calls, voice or text messages, hang-ups;

- unwanted emails, instant messages, messages through social media;

- unwanted cards, letters, flowers, or presents;

- watching or following from a distance, spying with a listening device, camera, or global positioning system (GPS);

- approaching or showing up in places, such as the victim's home, workplace, or school, when it was unwanted;

- leaving strange or potentially threatening items for the victim to find;

- sneaking into victim's home or car and doing things to scare the victim or let the victim know the perpetrator had been there.

The CDC asked about two additional tactics after respondents were identified as possible stalking victims:

- damaged personal property or belongings, such as in their home or car; and

- made threats of physical harm.

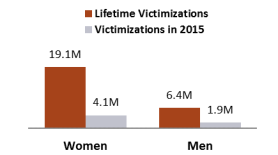

According to 2015 data from the CDC, 16.0% of women (19.1 million) and 5.8% of men (6.4 million) have been stalked by an intimate partner in their lifetimes. In the 12 months preceding the survey, approximately 4.5 million women and 2.1 million men were victims of stalking.70 See Figure 3.

Federal Programs Authorized by VAWA

The fundamental goals of VAWA are to prevent violent crime; respond to the needs of crime victims; learn more about crime; and change public attitudes through a collaborative effort by the criminal justice system, social service agencies, research organizations, schools, public health organizations, and private organizations. The federal government tries to achieve these goals primarily through federal grant programs that provide funding to state, tribal, territorial, and local governments; nonprofit organizations; and universities.

As previously mentioned, OVW administers the majority of VAWA-authorized programs, while other federal agencies, including OJP and the CDC, also manage VAWA programs. Since its creation in 1995 through FY2018, OVW has awarded more than $78 billion in grants and cooperative agreements to state, tribal, and local governments; nonprofit organizations; and universities.71

FY2018–FY2019 Appropriations

In FY2018 and FY2019, $553 million wasand $559 million, respectively, were appropriated for VAWA programs administered by OVW, OJP, and the CDC, as shown in Table 1. For program descriptions, authorization levels, and a five-year history of appropriations, see the Appendix.

|

Office and Program |

FY2018 VAWA Authorization Level |

FY2018 Enacted Appropriations and Set-Asides FY2019 Enacted Appropriations and Set-Asides |

|

|

Office on Violence Against Women |

|||

|

STOP (Services, Training Officers, and Prosecutors) Violence Against Women Formula Grant Program |

$222.00 |

$215.00 $215.00 |

|

|

Improving Criminal Justice Responses to Sexual Assault, Domestic Violence, Dating Violence, and Stalking Grant Program (also known as Grants to Encourage Arrest Policies or Arrest Program) |

$73.00 |

$53.00 $53.00 |

|

|

Civil Legal Assistance for Victims Grant Program |

$57.00 |

$45.00 $45.00 |

|

|

Tribal Governments Program |

($40.15) |

($40.45) |

|

|

Rural Domestic Violence, Dating Violence, Sexual Assault, Stalking, and Child Abuse Enforcement Assistance |

$50.00 |

$40.00 $42.00 |

|

|

Transitional Housing Assistance Grants for Victims of Sexual Assault, Domestic Violence, Dating Violence, and Stalking Program |

$35.00 |

$35.00 $36.00 |

|

|

Sexual Assault Services Program (SASP) |

$40.00 |

$35.00 $37.50 |

|

|

Grants to Reduce Domestic Violence, Dating Violence, Sexual Assault, and Stalking on Campus Program |

$12.00 |

$20.00 $20.00 |

|

|

Justice for Families Program (also known as Family Civil Justice Program or Grants to Support Families in the Justice System) |

$22.00 |

$16.00 $16.00 |

|

|

Consolidated Youth Oriented Program |

$11.00 $11.00 |

||

|

State and Territorial Sexual Assault and Domestic Violence Coalitions Program |

($10.75) |

($10.75) |

|

|

Grants to Enhance Culturally Specific Services for Victims of Domestic Violence, Dating Violence, Sexual Assault, and Stalking |

($7.45) |

($7.55) |

|

|

Tribal Domestic Violence and Sexual Assault Coalitions Grant Program |

($6.49) ($6.49) |

||

|

Training and Services to End Violence Against Women with Disabilities Grant Program |

$9.00 |

$6.00 $6.00 |

|

|

Grants for Outreach and Services to Underserved Populations |

($5.36) ($5.36) |

||

|

Enhanced Training And Services To End Abuse In Later Life Program |

$9.00 |

$5.00 $5.00 |

|

|

Grants to Tribal Governments to Exercise Special Domestic Violence Criminal Jurisdiction |

$5.00 |

$4.00 $4.00 |

|

|

Domestic Violence Homicide Prevention Initiative |

($4.00) ($4.00) |

||

|

Research and Evaluation on Violence Against Womend |

$3.50 $3.00 |

||

|

SASP Culturally Specific Services |

($3.50) |

($3.75) |

|

|

Tribal SASP |

($3.50) |

($3.75) |

|

|

SASP State Coalitions |

($3.15) |

($3.38) |

|

|

Rape Survivor Child Custody Actf |

$5.00 |

$1.50 |

$1.50 |

|

Research on Violence Against Indian Womend |

$1.00 $1.00 |

||

|

National Indian Country Clearinghouse on Sexual Assault |

$0.50 |

$0.50 |

|

|

National Resource Center on Workplace Responses to Domestic Violence, Dating Violence, Sexual Assault, and Stalking |

$1.00 |

$0.50 $1.00 |

|

|

SASP Tribal Coalitions |

($0.35) |

($0.38) |

|

|

Total OVW |

$492.00 $497.50 |

||

|

(Total OVW Set-Asides) |

($84.70) ($85.85) |

||

|

Office of Justice Programs |

|||

|

Court Appointed Special Advocates for Victims of Child Abuse |

$12.00 |

$12.00 $12.00 |

|

|

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

|||

|

Rape Prevention and Education Grants |

50.00 |

$49.43 |

$49.43 |

|

|

$553.43 |

$558.93 |

Source: FY2018 enacted amounts were taken from the joint explanatory statement to accompany P.L. 115-141, printed in the March 22, 2018, Congressional Record (pp. H2084-H2115). FY2019 enacted amounts were taken from H.Rept. 116-9. Set-aside amounts were provided by OVW.

Notes: Programs in this table include those authorized by the Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2013 (P.L. 113-4) as well as supplemental funding for VAWA programs under the Rape Survivor Child Custody Act. Numbers in parentheses are set-asides and are not included in the sum total amounts. FY2019 authorization levels are not provided, because authorizations of appropriations for VAWA programs have expired.

a. Set-asides are authorized in VAWA statute. For example, the Tribal Governments Program is funded by authorized set-asides from seven other OVW grant programs: STOP; Grants to Encourage Arrest Policies and Enforcement of Protection Orders; Rural Domestic Violence, Dating Violence, Sexual Assault, Stalking, and Child Abuse Enforcement Assistance; Civil Legal Assistance for Victims; Grants to Support Families in the Justice System; and Transitional Housing.

b. This program does not have a specific authorization but rather relies on several separate authorizations. Congress authorized $15 million annually from FY2014 through FY2018 for CHOOSE Children and Youth and $15 million annually from FY2014 through FY2018 for SMART Prevention. The Consolidated Youth Oriented Program is a combination of these authorizations. For more information, see "Consolidation of Grant Programs."

c. Technical assistance initiatives are generally authorized under 34 U.S.C. §12291(b)(11).

d. These funds are transferred from OVW to OJP.

e. A research agenda is authorized under 34 U.S.C. §12331, but a funding amount is not specified.

f. Under the Rape Survivor Child Custody Act, states are eligible to receive additional funds in their STOP and SASP formula grant awards if they meet the requirements of the act.

g. VAWA 2013 reauthorized appropriations ($1 million each year) for the study of violence against Indian women for FY2014 and FY2015 only.

h. Total authorized amounts are not provided because not all VAWA-authorized programs are included in this table. Only those that received funding in FY2018 and FY2019 are included.

FY2019FY2020 Appropriations

While authorizations of appropriations are due to expire before the end of the calendar year, the House, the Senate, and the Administration have all indicated that they intend to fund VAWA programs in FY2019for VAWA programs have expired,72 the Administration has requested FY2020 funding for VAWA-authorized programs. The Administration's budget request proposes to fund OVW at $485.50492.5 million for FY2019FY2020 (a 1% decrease from FY2019), all of which would be derived from a transfer from the Crime Victims Fund.72 The Senate committee-reported bill (S. 3072) would provide $498 million for OVW in FY2019, all of which would be derived from a transfer from the Crime Victims Fund. The House committee-reported bill (H.R. 5952) would provide $493 million in appropriations for OVW in FY2019.

In FY2019 continuing appropriations (P.L. 115-245), a conference report (H.Rept. 115-952) was filed that provided an extension of authorization for VAWA (specifically, "[a]ny program, authority, or provision, including any pilot program, authorized under the Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2013") through December 7, 2018. Thus far in FY2019, appropriations continued for all VAWA programs funded in FY2018 under P.L. 115-245.

|

OVW publishes large amounts of data on its programs. It submits biennial reports on its programs to Congress as well as other reports, such as reports on stalking, and makes them available on the website. OJP publishes both award data and VAWA-authorized research on its agency websites. For information on funding for The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) publishes grantee award data for the Rape Prevention and Education (RPE) program on the Tracking Accountability in Government Grants System (TAGGS). |

Past Reauthorizations and Changes to VAWA

Since it was enacted in 1994, VAWA has been reauthorized three times. Of note, the reauthorizations in 2000 and 2005 had broad bipartisan support, while the most recent reauthorization in 2013 had bipartisan support but faced greater opposition.7881 This section will provide comparatively more detail for the 2013 reauthorization because it was the most recent and some issues may remain relevant to current reauthorization discussions.

2000 Reauthorization

In 2000, Congress reauthorized VAWA through the Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act (P.L. 106-386; VAWA 2000). Modifications included additional protections for battered nonimmigrants,7982 a new program for victims of domestic violence, dating violence, sexual assault, and stalking in need of transitional housing, a requirement for grant recipients to submit reports on the effectiveness of programs, new programs designed to protect elderly and disabled women, mandatory funds to be used exclusively for rape prevention and education programs, and inclusion of victims of dating violence.8083

VAWA 2000 amended interstate stalking and domestic violence law to include (1) a person who travels in interstate or foreign commerce with the intent to kill, injure, harass, or intimidate a spouse or intimate partner, and who in the course of such travel commits or attempts to commit a crime of violence against the spouse or intimate partner; (2) a person who causes a spouse or intimate partner to travel in interstate or foreign commerce by force or coercion and in the course of such travel commits or attempts to commit a crime of violence against the spouse or intimate partner; (3) a person who travels in interstate or foreign commerce with the intent of violating a protection order or causes a person to travel in interstate or foreign commerce by force or coercion and violates a protection order; and (4) a person who uses the mail or any facility of interstate or foreign commerce to engage in a course of conduct that would place a person in reasonable fear of harm to themselves or their immediate family or intimate partner.8184

2005 Reauthorization

In 2005, Congress reauthorized VAWA through the Violence Against Women and Department of Justice Reauthorization Act (P.L. 109-162; VAWA 2005).8285 VAWA 2005 added protections for battered and/or trafficked nonimmigrants,8386 programs for American Indian victims, and programs designed to improve the public health response to domestic violence. The act emphasized collaboration among law enforcement; health and housing professionals; and women, men, and youth alliances, and it encourages community initiatives to address these issues.

This reauthorization enhanced penalties for repeat stalking offenders and expanded the federal criminal definition of stalking to include cyberstalking. It also amended the federal criminal code to revise the definition of the crime of interstate stalking to (1) include placing someone under surveillance with the intent to kill, injure, harass, or intimidate that person; and (2) require consideration of substantial emotional harm to the stalking victim.

2013 Reauthorization

Authorization for appropriations for the programs under VAWA expired in 2011; however, programs continued to receive appropriations in FY2012 and FY2013. In 2013, the 113th Congress reauthorized VAWA through the Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2013 (P.L. 113-4; VAWA 2013). Most VAWA grants were reauthorized from FY2014 through FY2018. This section briefly describes provisions of VAWA 2013.

Consolidation of Grant Programs

VAWA 2013 reauthorized most VAWA grant programs and authorized appropriations at a lower level, in general. It consolidated several VAWA grant programs, and in doing so authorized new grant programs. These actions are summarized below.

- The Grants to Support Families in the Justice System program was created by consolidating two previously authorized programs: (1) the Safe Havens for Children program (also referred to as Supervised Visitation), and (2) the Court Training and Improvements program.

8487 The purpose of this program is to improve the civil and criminal justice systems' responses to families with a history of domestic violence, dating violence, sexual assault, or stalking, or in cases involving allegations of child sexual abuse. - The Creating Hope Through Outreach, Options, Services, and Education for Children and Youth (CHOOSE Children & Youth) was created by consolidating two previously authorized programs: (1) Services to Advocate for and Respond to Youth (also referred to as Youth Services) and (2) Grants to Combat Domestic Violence, Dating Violence, Sexual Assault, and Stalking in Middle and High Schools (also referred to as Supporting Teens through Education and Protection, or STEP).

8588 The purpose of this program is to enhance the safety of youth and children who are victims of or exposed to domestic violence, dating violence, sexual assault, stalking, or sex trafficking. The program also aims to prevent future violence. - The Saving Money and Reducing Tragedies Through Prevention (SMART Prevention) was created by consolidating two previously authorized programs: (1) Engaging Men and Youth in Prevention and Grants to Assist Children and (2) Youth Exposed to Violence.

8689 The SMART Prevention program aims to prevent domestic violence, sexual assault, dating violence, and stalking through awareness and education programs, and also through assisting children who have been exposed to violence and abuse. In addition, this program aims to prevent violence by engaging men as leaders and role models. - The Grants to Strengthen the Healthcare System's Response to Domestic Violence, Dating Violence, Sexual Assault, and Stalking was created using the purpose areas of three previously unfunded programs—(1) Interdisciplinary Training and Education on Domestic Violence and Other Types of Violence and Abuse, (2) Research on Effective Interventions in the Health Care Setting, and (3) Grants to Foster Public Health Responses to Domestic Violence, Dating Violence, Sexual Assault, and Stalking—these programs were eliminated.

8790 The purpose of this program is to improve training and education for health professionals in preventing and responding to domestic violence, dating violence, sexual assault, and stalking.

VAWA Grant Provisions

VAWA 2013 established new provisions for all VAWA grant programs. It established a nondiscrimination provision to ensure that victims are not denied services and are not subjected to discrimination based on actual or perceived race, color, religion, national origin, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, or disability. It also enhanced protection of personally identifiable information of victims and specified the type of information that may be shared by grantees and subgrantees.8891 It also required that any grantee or subgrantee that provides legal assistance must comply with certifications required under the Legal Assistance for Victims Grant Program.89

The 2013 reauthorization also added, modified, or expanded several definitions of terms in VAWA. Examples include the following:

- The definition of domestic violence was revised to specifically include "intimate partners" in addition to "current and former spouses."

- The term linguistically was removed from the Culturally Specific Services Grant and the definition of "culturally specific services" was amended to address the needs of culturally specific communities.

- With respect to providing VAWA-related services, the act added the terms population specific services and population specific organizations, which focus on "members of a specific underserved population."

9093 - Underserved populations was redefined to include those who may be discriminated against based on religion, sexual orientation, or gender identity.

9194 - The definition of cyberstalking was expanded to include use of any "electronic communication device or electronic communication service or electronic communication system of interstate commerce."

9295

- A definition of rape crisis center was added, meaning "a nonprofit, nongovernmental, or tribal organization, or governmental entity in a State other than a Territory that provides intervention and related assistance ... to victims of sexual assault without regard to their age. In the case of a governmental entity, the entity may not be part of the criminal justice system ... and must be able to offer a comparable level of confidentiality as a nonprofit entity that provides similar victim services."

9396

- Individual in later life was defined as a person who is 50 years of age or older.

- Youth was defined as a person who is 11 to 24 years of age.

- The definition of rural state was revised to include states with more densely populated rural areas than under the prior definition.

94

97Accountability of Grantees

VAWA 2013 imposed new accountability provisions, including an audit requirement and mandatory exclusion from eligibility if a grantee is found to have an unresolved audit finding. Additionally, it required OVW to establish a biennial conferral process with state and tribal coalitions and technical assistance providers that receive OVW funding.9598 It prohibited conferences funded through cooperative agreements from using more than $20,000 in funding without prior written approval by DOJ officials.

Sexual Assault and Rape Kit Backlog

VAWA 2013 amended the DNA Analysis Backlog Elimination Act of 2000 (P.L. 106-546)9699 to strengthen audit requirements for sexual assault evidence backlogs. It also required that for each fiscal year through FY2018, not less than 75% of the total Debbie Smith grant97100 amounts be awarded to carry out DNA analyses of samples from crime scenes for inclusion in the Combined DNA Index System (CODIS)98101 and to increase the capacity of state or local government laboratories to carry out DNA analyses.

Additionally, VAWA 2013 expanded the purpose areas of several VAWA grants to respond to the needs of sexual assault survivors by addressing rape kit backlogs. It also established a new requirement that at least 20% of funds within the STOP (Services, Training, Officers, Prosecutors) program and 25% of funds within the Grants to Encourage Arrest Policies and Enforce Protection Orders program be directed to programs that meaningfully address sexual assault.

Trafficking in Persons

VAWA 2013 amended and authorized appropriations for the Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000 (Division A of P.L. 106-386).99102 It enhanced measures to combat trafficking in persons, and amended the purpose areas for several grants to address sex trafficking. VAWA 2013 also clarified that victim services and legal assistance include services and assistance to victims of domestic violence, dating violence, sexual assault, or stalking who are also victims of severe forms of trafficking in persons.100

American Indian Tribes

VAWA 2013 included new provisions for American Indian tribes. It granted authority to tribes to exercise special domestic violence criminal jurisdiction and civil jurisdiction to issue and enforce protection orders over any person.101104 It also created a voluntary two-year pilot program for tribes that make a request to the Attorney General to be designated as a participating tribe to have special criminal jurisdiction over domestic violence cases. (Note: The Attorney General may grant a request after concluding that the tribe's criminal justice system has adequate safeguards in place to protect defendants' rights.) In addition, it created a new grant program to assist tribes in exercising special criminal jurisdiction in cases involving domestic violence.

VAWA 2013 also expanded the purpose areas of grants for tribal governments and coalitions to

- include sex trafficking;

- develop and promote legislation and policies that enhance best practices for responding to violent crimes against Indian women; and

- raise awareness of and response to domestic violence, including identifying and providing technical assistance to enhance access to services for Indian women victims of domestic and sexual violence, including sex trafficking.

Battered Nonimmigrants

VAWA 2013 extended VAWA coverage to derivative children whose self-petitioning parent died during the petition process, a benefit currently afforded to foreign nationals under the family-based provisions of the Immigration and Naturalization Act (INA).102105 It also exempted VAWA self-petitioners, U visa petitioners,103106 and battered foreign nationals from being classified as inadmissible for legal permanent resident status if their financial circumstances raised concerns about them becoming potential public charges.104107 Additionally, it amended the INA to expand the definition of the nonimmigrant U visa to include victims of stalking.

VAWA 2013 added several new purpose areas to the Grants to Encourage Arrest Policies and Enforcement of Protection Orders program (Arrest Program), one of which was to improve the criminal justice system response to immigrant victims of domestic violence, sexual assault, dating violence, and stalking.

Underserved Populations

In addition to expanding the definition of underserved populations, VAWA 2013 established several new grant provisions to address the needs of underserved populations. It required STOP implementation plans to include demographic data on the distribution of underserved populations within states and how states will meet their needs. It expanded the purpose areas of the Grants to Combat Violent Crimes on Campuses program to address the needs of underserved populations on college campuses. It also dedicated 2% of annual appropriated funding for the Arrest and STOP programs to Grants for Outreach to Underserved Populations, a previously unfunded VAWA program.

Housing

VAWA 2013 added housing rights for victims of domestic violence, dating violence, sexual assault, and stalking, including a provision stating that applicants may not be denied public housing assistance based on their status as victims of domestic violence, dating violence, sexual assault, or stalking. It also required each executive department carrying out a covered housing program105108 to adopt a plan whereby tenants who are victims of domestic violence, dating violence, sexual assault, or stalking can be transferred to another available and safe unit of assisted housing. Additionally, it required the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development to establish policies and procedures under which a victim requesting such a transfer may receive Section 8 assistance under the U.S. Housing Act of 1937.106

Under the VAWA-authorized Transitional Housing Assistance Grant program, the act ensured that victims receiving transitional housing assistance are not subject to prohibited activities, including background checks or clinical evaluations, to determine eligibility for services. It removed the requirement that victims must be "fleeing" from a violent situation in order to receive transitional housing assistance. It also specified that transitional housing services may include employment assistance.

Institutions of Higher Education (IHEs)

VAWA 2013 made several changes to higher education policy. It amended the Clery Act107110 and incorporated provisions from the Campus Sexual Violence Elimination Act.108111 These provisions required, among other things, IHEs to report data on domestic violence, dating violence, and stalking in annual security reports (ASRs). Newly reportable crime categories included domestic violence, dating violence, and stalking. VAWA 2013 also added two new categories of bias applicable to hate crime reporting (i.e., national origin and gender identity).

VAWA 2013 required ASRs to include a statement of the IHE's policy on programs to prevent sexual assaults, domestic violence, dating violence, and stalking; policies to address these incidents if they occur, including a statement on the standard of evidence that will be used during an institutional conduct proceeding regarding these crimes;109112 and primary prevention programs to promote awareness of these crimes for incoming students and new employees, as well as providing ongoing awareness and prevention training for students and faculty. It also required that crime statistics on victims who were "intentionally selected" because of their national origin or gender identity are recorded and reported according to category of prejudice.

In addition, VAWA 2013 required that students and employees receive written notification of available victim services including counseling, advocacy, and legal assistance, as well as options for modifying a victim's academic, living, transportation, or work arrangements. Victims were to be notified of their rights, including their right to notify or not notify law enforcement and campus authorities of a crime of sexual violence. The law also required that officials who investigate a complaint or conduct an administrative proceeding regarding sexual assault, domestic violence, dating violence, or stalking receive annual training on how to conduct investigations or proceedings that protect the safety of victims and promote accountability.110

Other Changes

VAWA 2013 amended rules for sexual acts in federal custodial facilities by adding "the commission of a sexual act" as grounds for civil action by a federal prisoner and mandating that detention facilities operated by the Department of Homeland Security and custodial facilities operated by the Department of Health and Human Services adopt national standards established pursuant to the requirements in the Prison Rape Elimination Act of 2003 (P.L. 108-79). VAWA 2013 also enhanced criminal penalties for assaulting a spouse, intimate partner, or dating partner.111

Rape Survivor Child Custody Act

In May 2015, as part of the Justice for Victims of Trafficking Act (Title IV, P.L. 114-22), the Rape Survivor Child Custody Act was enacted into law. It requires the Attorney General (through OVW) to increase grant funding under the STOP and SASP formula grant programs to states that have a law allowing the mother of a child conceived through rape to seek court-ordered termination of the parental rights of her rapist. The increase in formula grants is allowed to be provided for a total of four two-year periods (eight years), and is equal to not more than 10% of the total amount of funding provided to the state averaged over the previous three years. Of the increased funding, 25% is for STOP grants and 75% for the SASP grants. The Rape Survivor Child Custody Act authorized $5 million a year for FY2015 through FY2019 for the grant increases.112

Current Efforts to Reauthorize VAWA

There are several issues that Congress may consider in current reauthorization efforts. These include, but are not limited to, improvements to data collection, assessing tribal jurisdiction over non-tribal members who commit VAWA-related crimes on tribal lands, new approaches for law enforcement in assisting victims, and enforcement of the federal prohibition on firearms for those convicted of a misdemeanor crime of domestic violence and those who are subject to a domestic violence protective order. Congress may also consider further changes to VAWA programs. The Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2019 (H.R. 1585), as passed by the House, would address some of these issues. Among other things, it would reauthorize funding for VAWA programs and authorize new programs; amend and add definitions used for VAWA programs; amend federal criminal law relating to firearms, custodial rape, and stalking; and expand tribal jurisdiction over certain crimes committed on tribal lands.

Improvements to Data Collection

Congress may address issues concerning limited law enforcement data at the national level on the crimes of domestic violence and stalking. The data are limited because the UCR does not currently collect information on these offenses from state and local agencies like it does for its traditional violent and property crime offense categories.113116 In 2019, the UCR program plans to begin collecting domestic violence offense data through the National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS). NIBRS also includes stalking as part of an intimidation offense category. Even though the NIBRS data are not yet nationally representative,114117 the FBI states that it is transitioning its UCR program to a "NIBRS only data collection" by 2021.115118 Congress may consider options to expand the NIBRS program sooner than 2021 or to adjust the UCR program in other ways, such as by requiring the FBI to collect data on stalking as its own offense under NIBRS rather than incorporating it into the intimidation offense category.

Congress may also address the availability of data on the sexual assault kit (SAK, or rape kit) backlog. According to the National Institute of Justice (NIJ), "it is unknown how many unanalyzed [SAKs] there are nationwide."116119 NIJ notes that while there are many reasons why there are no data on the number of untested SAKs in law enforcement's possession, one contributing factor is that there is no national system for collecting these data. Also, tracking and counting SAKs is an antiquated process in many jurisdictions (often done in nonelectronic formats), and the availability of computerized evidence-tracking systems has been an issue for many jurisdictions for years.

The Joyful Heart Foundation, a grassroots organization, addressed the SAK data void by attempting to count the backlog (through public records requests) and track data in cities and states across the country. While the organization's data are incomplete, it has estimates of rape kit backlogs for various cities and states. Thus far, it has identified approximately 41 municipal and county jurisdictions with known rape kit backlogs ranging from several hundred to thousands—its current total is 40,000 untested SAKs.117

Congress may assess the SAK backlog and debate if the federal response should be changed as the issue evolves and agencies, including NIJ, capture the full breadth of the problem.

H.R. 1585, as passed by the House, would authorize several new activities related to increasing or improving data collection. These include, but are not limited to, the following:

- requiring the Attorney General to establish an interagency working group to study federal efforts to collect data on sexual violence and to make recommendations on the harmonization of such efforts,

- authorizing funding for tribal governments to improve data collection and to enter information into and obtain information from national crime information databases,121 and

- requiring NIJ to prepare a report on the status of women in federal incarceration—this requirement allows for inmate and personnel data to be collected from the Bureau of Prisons.

Tribal Jurisdiction

As discussed previously, VAWA 2013 granted authority to American Indian tribes to exercise special domestic violence criminal jurisdiction and civil jurisdiction to issue and enforce protection orders over any person, including non-tribal members.118122 As of March 2018, 18 tribes were exercising this authority.119123 These tribes have reported 143 arrests of 128 non-tribal individuals, which led to 74 convictions and five acquittals with 24 cases pending as of March 2018.120124 According to the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI), tribes are exercising jurisdiction "with careful attention to the requirements of federal law and in a manner that upholds the rights of defendants."121125

While NCAI issued its assessment report in 2018, Congress also may elect to assess implementation in the five years since this authority was granted. If it so chooses, Congress may require the Government Accountability Office (GAO) to evaluate tribal jurisdiction.

Congress may elect to grant special jurisdiction over non-tribal members for additional VAWA crimes such as sexual assault and stalking, as well as non-VAWA crimes. NCAI stated in its assessment report that many implementing tribes were unable to prosecute non-tribal members for many crimes that co-occur with domestic violence such as drug and alcohol offenses.

H.R. 1585, as passed by the House, would amend tribal criminal jurisdiction authorized under Section 204 of the Indian Civil Rights Act. Among other changes, tribal jurisdiction over criminal behavior on tribal lands would consist of domestic violence (H.R. 1585 would also expand the definition of domestic violence used for tribal jurisdiction), as well as obstruction of justice, assaulting a law enforcement officer, sex trafficking, sexual violence, and stalking.126

New Approaches for Law Enforcement

As there are further developments in the fields of criminal justice and public health, researchers and practitioners report new and developing approaches and methods for law enforcement and other criminal justice personnel in working with victims of domestic violence, sexual assault, dating violence, and stalking. Congress may consider these new approaches when debating additions to grant purpose areas or encouraging states to adopt certain practices. For example, over the last decade there has been a push for criminal justice professionals to incorporate trauma-informed policing and response policies.122127 Congress may consider requiring law enforcement grantees to incorporate trauma-informed training and policies into their required training or standard operating procedures or creating new funding opportunities to develop these trainings and policies.123128 Of note, OVW has supported several initiatives related to trauma-informed approaches.124129 Other new and developing approaches include, but are not limited to, new protocols for police officers about when they would activate their body-worn cameras as they interact with victims of domestic violence, sexual assault, dating violence, or stalking and so-called "red flag" laws that allow law enforcement or family members to petition a court to have firearms removed from those who are a danger to themselves or others.

H.R. 1585, as passed by the House, would authorize a new demonstration program under OVW to promote trauma-informed training for law enforcement. Through this program, OVW would make grants on a competitive basis to eligible entities130 to implement evidence-based or promising policies and practices to incorporate trauma-informed techniques designed to prevent re-traumatization of crime victims and improve communication between victims and law enforcement officers, among other purpose areas, in an effort to increase the likelihood of successful investigations and prosecutions of reported crime in a manner that protects the victim to the greatest extent possible.

Domestic Violence and Federal Prohibition of Possession of Firearms

The Gun Control Act (GCA)125131 prohibits certain individuals from possessing firearms, including individuals who have been convicted of a misdemeanor crime of domestic violence126132 and those who are subject to a protective order involving an intimate partner or child of an intimate partner.127133 Congress may consider any number of issues surrounding prohibitions on firearms possession and matters of domestic violence, but the issue of enforcement of domestic violence and protection order prohibitions has been subject to some debate.128

While there is a federal process for preventing those convicted of a misdemeanor crime of domestic violence or those subject to a protective order from purchasing a firearm,129134 there is not a federal process for these individuals to surrender their firearms. The process is left up to states and local jurisdictions, which vary in their approaches to enforcing these prohibitions. In some jurisdictions, the process for informing defendants/respondents they must surrender their firearms can vary by judge.130135 Of note, VAWA 2005 established a provision that required states or units of local government to certify that its judicial policies and practices included notification to domestic violence offenders of the firearms prohibitions in Section 922(g)(8) and (g)(9) of Title 18 in order to be eligible to receive STOP funding.131136 Congress may choose to take further steps to ensure the enforcement of these prohibitions, such as adding to the certification requirement, or it might leave the decisions to the states, some of which have enacted laws requiring the removal of firearms from those subject to the prohibitions.

H.R. 1585, as passed by the House, includes several provisions that seek to reduce firearms-related intimate partner violence. It would amend federal law to prohibit persons convicted of misdemeanor stalking crimes from receiving or possessing a firearm or ammunition, and revise related provisions governing domestic violence protection orders and the definition of "intimate partner" under current law. H.R. 1585 also includes other provisions related to improving enforcement of federal firearm possession prohibitions under 18 U.S.C. §922, subsections (g)(8), (g)(9), and (g)(10).137

Other Changes to VAWA Programs

In the next effort to reauthorize VAWA, Congress may debate additional changes to VAWA programs such as adding new grant purpose areas or additional crimes, creating new programs, or consolidating existing programs. Examples of potential changes Congress may consider should it choose to reauthorize VAWA appropriations include the following:

- Female genital mutilation

(FGM), a federal crime,or female genital cutting (FGM/C) may be added to grant programs in a variety of ways. For example, it can be added as a crime for services eligibility, or Congress may try to encourage or require states (in order to receive grant funding) to make FGM/C a crime.132138

- Many VAWA grant programs fund the same services and the same organizations.

133139 For example, nine separate VAWA programs may be used to fund emergency shelter or transitional housing.134140 Congress may consider streamlining funding into fewer, larger grant programs. Currently, OVW administers 4 formula grant programs and 15 discretionary grant programs.135141

- Congress may opt to support domestic violence courts.

136142 While some grantees already use funds for this purpose and OVW has provided technical assistance to fund model domestic violence courts,137143 Congress may elect to create a program to support these specialized courts. - While there is a large amount of grantee data available on the VAWA programs administered by OVW, grantee data from the Rape Prevention and Education (RPE) formula grant program administered by the CDC are limited. Congress may choose to require the CDC to submit reports on the activities supported with RPE funds.

H.R. 1585, as passed by the House, would define FGM/C for VAWA grant purposes, and amend the purpose areas of three VAWA grant programs (STOP, Outreach and Services to Underserved Populations, and CHOOSE Children and Youth) to include providing culturally specific victim services regarding responses to, and prevention of, FGM/C. The bill would also require the Director of the FBI to classify FGM/C, or female circumcision, as a part II crime in the UCR (see "Categories of Crime Addressed through VAWA" for discussion of UCR crime data).

H.R. 1585 would also amend the Rape Prevention and Education Grant Program to require the CDC Director to submit to Congress a report on the activities funded by grants and best practices relating to rape prevention and education.

H.R. 1585, if enacted, would make many other changes that are not discussed in detail in this report. These include changes to definitions used for VAWA grant purposes,144 new housing protections for victims, and the creation of new grant programs that address issues such as lethality assessment in domestic violence cases and economic security for victims. Of note, H.R. 1585 would reauthorize funding for most VAWA programs145 for FY2020-FY2024.

Appendix. Additional Data for VAWA Programs

The Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2013 (P.L. 113-4) authorized appropriations for most VAWA programs for FY2014 through FY2018.138146 Table A-1 provides descriptions of currently funded VAWA programs, Table A-2 provides a list of unfunded VAWA-authorized programs, and Table A-3 provides a five-year funding history of VAWA programs by total funding amounts for each administrative office. For more-detailed program funding, see Table 1.

Table A-1. Current VAWA-Authorized Programs Funded Under the Departments of Justice and Health and Human Services

|

Program and U.S. Code Citation (by Administrative Agency) |

Purpose Areas |

Eligible Applicants |

|

Office on Violence Against Women Formula Grant Programs: |

||

|

STOP (Services, Training, Officers, and Prosecutors) Formula Grant Program 34 U.S.C. §§10441, 10446 – 10451, and 28 C.F.R. Part 90 |

The purpose of this formula grant program is to enhance the capacity of local communities to develop and strengthen effective law enforcement and prosecution strategies to combat violent crimes against women and to develop and strengthen victim services in cases involving violent crimes against women. |

States, the District of Columbia, the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, American Samoa, Guam, and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands.a |

|

Sexual Assault Services Formula Grant Program (SASP) 34 U.S.C. §12511 |

The purpose of this formula grant program is to provide intervention, advocacy, accompaniment, support services, and related assistance for adult, youth, and child victims of sexual assault, family and household members of victims, and those collaterally affected by the sexual assault through rape crisis centers and other nonprofit organizations. |

States, the District of Columbia, the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, American Samoa, Guam, and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands. |

|

State and Territorial Sexual Assault and Domestic Violence Coalitions Program 34 U.S.C. §10441(c) |

The purpose of this formula grant program is for state and territorial coalitions to coordinate victim service activities and provide support to member rape crisis centers, member battered women's shelters, and other service providers. |

State and territorial coalitions.b |

|

Grants to Tribal Domestic Violence and Sexual Assault Coalitions Program 34 U.S.C §10441(d) and 34 U.S.C. §12511(d) |

The purpose of this formula grant program is to support the development and operation of nonprofit, nongovernmental tribal domestic violence and sexual assault coalitions. Tribal coalitions provide education, support, and technical assistance to member Indian service providers and tribes to enhance their response to victims of domestic violence, dating violence, sexual assault, and stalking. |

Tribal coalitions.c |

|

Office on Violence Against Women Discretionary Grant Programs: |

||

|

Improving Criminal Justice Responses to Sexual Assault, Domestic Violence, Dating Violence, and Stalking Grant Program (also known as Grants to Encourage Arrest Policies, or Arrest Program) 34 U.S.C. §§10461-10465 |

The purpose of this grant program is to encourage partnerships between state, local, and tribal governments; courts; victim service providers; coalitions; and rape crisis centers to ensure that sexual assault, domestic violence, dating violence, and stalking are treated as serious violations of criminal law |

States; the District of Columbia; the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico; the U.S. Virgin Islands; American Samoa; Guam; the Northern Mariana Islands tribal governments; units of local government; state, tribal, territorial, and local courts (including juvenile courts); state, tribal, and territorial domestic violence or sexual assault coalitions or victim service providers that partner with a state, tribal government, or unit of local government.d |

|

Civil Legal Assistance for Victims Grant Program 34 U.S.C. §20121 |

The purpose of this grant program is to strengthen and increase the availability of civil and criminal legal assistance for adult and youth victims of sexual assault, stalking, domestic violence, and dating violence through innovative and collaborative programs. Funds are used to provide direct legal services to victims in legal matters relating to or arising out of that abuse or violence, at minimal or no cost to the victims. |

Private, nonprofit organizations; tribal governments and organizations; territorial organizations; and publicly funded organizations not acting in a governmental capacity (e.g., law schools). |

|

Tribal Governments Program 34 U.S.C. §10452 |

The purpose of this grant program is to develop and enhance effective plans for tribal governments to reduce crimes of violence against American Indian women who are victims of domestic violence, dating violence, sexual assault, sex trafficking, and stalking and improve services for these women; increase the ability of a tribal government to respond to domestic violence, dating violence, sexual assault, sex trafficking, and stalking; strengthen the tribal criminal justice system; create community education and prevention campaigns; address the needs of children who witness domestic violence; provide supervised visitation and safe exchange programs; and provide transitional housing assistance and legal assistance. |

Tribal governments; and authorized designees of tribal governments. |

|

Rural Domestic Violence, Dating Violence, Sexual Assault, Stalking, and Child Abuse Enforcement Assistancee 34 U.S.C. §12341 |

The purpose of this grant program is to enhance the safety of victims of domestic violence, dating violence, sexual assault, and stalking by supporting projects uniquely designed to address and prevent these crimes in rural jurisdictions. |

States; the District of Columbia; the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico; Guam; American Samoa; the U.S. Virgin Islands; the Northern Mariana Islands; tribal governments; units of local government; nonprofit, public or private organizations, including tribal organizations. Applicants must propose to serve rural areas or rural communities, as defined in statute. |

|

Transitional Housing Assistance Grants for Victims of Sexual Assault, Domestic Violence, Dating Violence, and Stalking Program 34 U.S.C. §12351 |