Burma’s Political Prisoners and U.S. Policy

Changes from September 24, 2018 to May 17, 2019

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Burma's Political Prisoners and U.S. Policy: In Brief

Contents

- Overview

- Current Status of Political Prisoners in Burma

- Political Prisoners and the NLD-Led Government

- Prisoner Releases

- Continuing Arrests and Trials of Political Prisoners

- The Case of Aung Ko Htwe

- The Case of Kyaw Soe Oo and Wa Lone

- The Case of Lum Zawng, Nang Pu, and Zau Jet

- Definition of Political Prisoners

- Problematic Laws

- Civilian Government Authority over Criminal Cases

- Pending Legislation

Issues for U.S. Policy

Summary

Despite a campaign pledge that they "would not arrest anyone as political prisoners," Aung San Suu Kyi and the National League for Democracy (NLD) have failed to fulfil this promise since they took control of Burma's Union Parliament and the government's executive branch in April 2016. While presidential pardons have been granted for some politicalpolitical prisoners, people continue to be arrested, detained, tried, and imprisoned for alleged violations of Burmese laws, some dating back to British colonial rule.

. According to the Assistance Association of Political Prisoners (Burma), or AAPP(B), a Thailand-based, nonprofit human rights organization formed in 2000 by former Burmese political prisoners, there were 275331 political prisoners in Burma as of the end of July 2018April 2019.

During its twothree years in power, the NLD government has provided pardons for Burma's political prisoners on threesix occasions. Soon after assuming office in April 2016, former President Htin Kyaw and State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi took steps to secure the release of nearly 235 political prisoners. On May 23, 2017, former President Htin Kyaw granted pardons to 259 prisoners, including 89 political prisoners. On April 17, 2018, current President Win Myint pardoned 8,541 prisoners, including 36 political prisoners.

Aung San Suu Kyi and her government, as well as the Burmese military, however, also have demonstrated a willingness to use Burma's laws to suppress the opinions of its political opponents and restrict press freedoms. The NLD-led government arrested two Reuters reporters who had reported on alleged murders of Rohingya by Tatmadaw soldiers, Kyaw Soe Oo and Wa Lone, in December 2017 and charged them with violating the Official Secrets Act of 1923. The two reporters allegedly were given "secret documents" by Myanmar Police officers. Despite evidence that the documents had been given to the reporters as part of a police "sting operation," on September 3, 2018, the judge sentenced the two reporters to seven yearsOn September 3, 2018, the two reporters were sentenced to seven years in prison. Kyaw Soe Oo and Wa Lone were granted a presidential pardon on May 7, 2019, after serving 511 days in prison. In addition, Aung Ko Htwe was sentenced to two years in prison with hard labor on March 28, 2018, following his August 2017 interview with Radio Free Asia about his allegations that he was forced by the Tatmadaw to become a "child soldier."

The Union Parliament has repealed or amended a few of the numerous laws that authorities use to arrest and prosecute people for political reasons, and further has passed new laws that some observers see as limiting political expression and protection of human rights. In addition, the Tatmadaw, which directly or indirectly control the nation's security forces (including the Myanmar Police Force) and the Tatmadaw's leadership, has not demonstrated an interest in ending Burma's history of political imprisonment.

The Burma Political Prisoners Assistance Act (H.R. 2327) would make it U.S. policy to support the immediate and unconditional release of "all prisoners of conscience and political prisoners in Burma," and require the Secretary of State to "provide assistance to civil society organizations in Burma that work to secure the release of prisoners of conscience and political prisoners in Burma."Congress may consider these issues when it examines U.S. policy toward Burma, and Tatmadaw leaders have brought multiple defamation cases against journalists who publish stories critical of Burma's military.

policyU.S. policy in Burma. Congress may also choose to assess how other important issues in Burma should influence U.S. policy, including efforts to end the nation's ongoing low-grade civil war, the forced deportation of more than 700,000 Rohingya from Rakhine State, and prospects for constitutional and legal reform designed to establish a democratically elected civilian government that respects the human rights and civil liberties of all Burmese people.

Overview

The existence and treatment of political prisoners in Burma (Myanmar)1 has been a central issue in the formulation of U.S. policy toward Burma for more than 25 years. The arrest, detention, prosecution, and imprisonment of Burmese political prisoners—including Aung San Suu Kyi2—frequently were cited as reasons for imposing political and economic sanctions on Burma and the leaders of its ruling military junta. The release of political prisoners was often listed as a necessary condition for the repeal of those sanctions.3 When announcing waivers of existing sanctions, the Obama Administration often cited progress on the release of political prisoners as evidence for why the waiver was warranted.4

During a discussion of the human rights situation in Burma during the 34th session of the U.N. Human Rights Council in March 2017, William J. Mozdzierz, Director of the Office of Human Rights and Humanitarian Affairs within the State Department's Bureau of International Organization Affairs, stated that the U.S. government was "concerned by new political arrests under the current [Burmese] government," and urged "the [Burmese] government to immediately and unconditionally release all political prisoners, and to drop charges against individuals for taking part in protected political activities."5 What actions, if any, the 115116th Congress or the Trump Administration may take with respect to U.S. policy toward Burma may hinge, in part, on the issue of political prisoners in Burma.

SevenEight years have passed since Burma's ruling military junta, the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC), transferred power over to a newly reconstituted Union Parliament and President Thein Sein, a retired general and the SPDC's last Prime Minister. In 2016, Aung San Suu Kyi and the National League for Democracy (NLD) assumed control over the Union Parliament after NLD's landslide victory in the 2015 parliamentary elections.6 Although both the Thein Sein and NLD-led governments periodically pardoned political prisoners, authorities continue to arrest, detain, prosecute, and imprison people for peacefully expressing their political opinions.

One reason that controversy over political imprisonment persists in Burma is the lack of agreement on the definition of "political prisoner." Some in Burma would restrict the definition to "prisoners of conscience"; others prefer a broader definition that would include persons who took up arms against the SPDC and the Burmese military. Efforts to forge an official definition for political prisoners during the Thein Sein government were unsuccessful. So far, the NLD-led government has made little progress on the definition issue.

A second reason the issue of political imprisonment persists in Burma is the existence of many laws—some dating back to the time of British colonial rule—that restrict freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, and freedom of the press. Various human rights organizations have identified several Burmese laws that violate international standards on these freedoms. Because these laws remain in force, Burmese security personnel can arrest, detain, and prosecute people for their political views. Burma's courts have also shown a willingness to convict people for their political views. During the Thein Sein government, the Union Parliament made some progress on legal reform, but also passed new laws that some observers maintain restrict political expression. Since the NLD took control of the Union Parliament, little progress has been made on repealing or revising Burma's questionable laws.

A third reason the issue of political imprisonment persists in Burma has to do with who holds administrative authority over Burma's criminal cases. All security forces in Burma—including the military (or Tatmadaw), the Myanmar Police Force (MPF), the Border Guard Police, and local militias—directly or indirectly report to the Tatmadaw's Commander-in-Chief Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, and not to President Win Myint or the Union Parliament. As a result, people will continue to be arrested for political expression, in accordance with existing Burmese laws, so long as Min Aung Hlaing supports such a policy. President Win Myint does have authority over the prosecution of criminal offenses and the power to grant amnesty to convicted criminals.

If addressing political imprisonment remains a priority in U.S. policy toward Burma, then the 115116th Congress and the Administration could consider several options, such as reimposing sanctions and restrictions previously waived, or providing assistance in repealing or revising problematic laws or the provisions in the 2008 constitution. However, it may be useful for such options to be evaluated in the context of and with consideration of the possible impact on other priorities in U.S. relations with Burma, including

- :the creation of a democratically elected civilian government in Burma;

- the protection of the human rights of the people of Burma;

- progress toward greater economic prosperity for the people of Burma; and

- the establishment of direct civilian control over the Tatmadaw and the rest of Burma's security forces.

Current Status of Political Prisoners in Burma

The number of political prisoners in Burma fluctuates over time, depending on the termination of prison sentences, the status of pending trials, and the arrest and detention of new alleged political prisoners by Burma's security forces. The number also varies depending on which definition of "political prisoner" is used when categorizing cases.

The figures released by the Assistance Association of Political Prisoners (Burma), or AAPP(B), in its monthly report on political prisoners are widely used by the Burmese media, the international press, and the State Department, as a comparatively reliable estimate of the number of political prisoners in Burma. The AAPP(B) is a nonprofit human rights organization formed in 2000 by former Burmese political prisoners.

For over a decade, the AAPP(B) has released a monthly report on the number of political prisoners in Burma, based on its definition of political prisoner (see "Definition of Political Prisoners" below) and its network of researchers who monitor Burma's security system for information on alleged political prisoner arrests, detentions, trials, and incarceration. The monthly reports include a description of related events of the past month and a detailed list containing the names, alleged violation, prison (where applicable), sentence (where applicable), and political affiliation (if any) of each political prisoner.

|

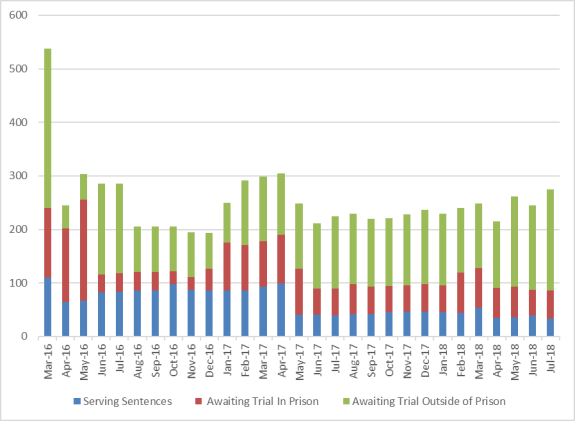

Figure 1. Political Prisoners in Burma By Status; Since March 2016 |

|

|

Source: AAPP(B) data. |

According to the AAPP(B), there were 275331 political prisoners in Burma as of the end of July 2018April 2019.7 Of those, 3348 were serving prison sentences, 5390 were being held in detention awaiting trial, and 189193 were awaiting trial outside of prison (see Figure 1). The number of political prisoners in Burma declined sharply after the NLD-led government took power in April 2016, but has generally remained between 200 and 300 people since then (see Figure 1).

Political Prisoners and the NLD-Led Government

The success of Aung San Suu Kyi and the National League for Democracy (NLD) in Burma's 2015 parliamentary elections raised the hopes of many in Burma that the arrest and detention of political prisoners would soon come to an end. During his term in office (2011-2016), former President Thein Sein promised to release all "prisoners of conscience" and at one point pledged that there would be no more "prisoners of conscience" in Burmese prisons by the end of 2014. According to most observers, he failed to fulfill his pledge. In January 2016, an NLD spokesperson told the press that the new government once in power would adopt an official definition of "political prisoner" and "would not arrest anyone as political prisoners."8 The spokesperson also stated that the NLD-led government "can control the arresting of political prisoners in accordance with existing laws," but did not elaborate on how that would be accomplished.9

Prisoner Releases

Soon after assuming office in April 2016, former President Htin Kyaw and State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi took steps to secure the release of nearly 235 political prisoners.10 On April 7, 2016, the Office of the State Counsellor announced that "releasing prisoners of conscience who are behind bars for their involvement in peaceful political activities is one of the priorities of the new government."11 The following day, Aung San Suu Kyi ordered that charges be dropped for 114 people facing charges for their participation in a peaceful protest against a proposed National Education Bill. On April 16, 2016—Burma's traditional New Year—President Htin Kyaw issued Order 33/2016 granting amnesty to 83 political prisoners. The amnesty was reportedly granted to "make people feel happy and peaceful, and (promote) national reconciliation during the New Year."12 According to the Ministry of Home Affairs, between April and mid-August 2016, the NLD-led government released 457 people facing trial for political activity, and 274 political cases were closed.13

On May 23, 2017, President Htin Kyaw granted amnesty to 259 prisoners in recognition of the second 21st Century Panglong Peace Conference, held on May 24-29, 2017. On April 17, 2018, current President Win Myint pardoned 8,541 prisoners, including 36 political prisoners.14 In its comments on the April pardons, AAPP(B) stated the following:

In light of the Presidential pardons, persecuting journalists for seeking the truth and others for speaking leaves a bitter taste in the mouth, particularly considering NLD's broken promise, made in 2016, that it would release all political prisoners when it came to power.15

President Win Myint has issued three separate prisoner pardons in 2019. On April 17, 2019, he granted amnesty to 9,551 prisoners, of which 2 were considered political prisoners according to AAPP(B). On April 26, 2019, 6,948 additional prisoners received a presidential pardon. On May 7, 2019, President Win Myint pardoned 6,520 prisoners, bringing the total for the year to 23,019.

According to AAPP(B), the three releases in 2019 included 20 political prisoners. The most prominent among them were the journalists Kyaw Soe Oo and Wa Lone. The released political prisoners also included 6 individuals imprisoned under the Unlawful Associations Act for their alleged association with one of Burma's ethnic armed organizations (EAOs), 5 people sentenced for violations of the Telecommunications Law, and 4 persons convicted of violating Penal Code 505(b). These three laws are among a number of Burmese laws that have been identified as unduly restricting human rights and civil liberties (see "Problematic Laws").

According to a spokesperson from the State Counsellor's Office, 27 people with affiliations with three EAOs—the All Burma Students' Democratic Front (ABSDF), the Restoration Council of Shan State (RCSS) and the Shan State Progressive Party (SSPP)—were released as part of peace and national reconciliation efforts.16

Continuing Arrests and Trials of Political Prisoners

In between the episodic presidential pardons, the NLD-led government has continued to arrest, detain, try, and convict individuals for political reasons using various laws, some of which date back to British colonial rule (see "Problematic Laws"). According to the AAPP(B), 2025 of the 3348 political prisoners serving sentences as of the end of July 2018April 2019 were convicted under the Unlawful Association Act of 1908 for their alleged association with one of Burma's ethnic armed organizations (EAOs). In addition, 68 of the 242 political prisoners awaiting trial have been charged with violations of the Right to Peaceful Assembly and Peaceful Procession Law of 2011. Another 72 people, who were protesting the government's expropriation of land, have been changed with "committing mischief" under Article 427 of Burma's Penal Code. Sixty-three people have been accused ofa prohibited EAO. Another 4 people were imprisoned under Section 505(b) of the Penal Code, which makes it illegal to "cause fear or alarm to the public." In addition, 5 of those in prison were convicted for violating Section 66(d) of the Telecommunications Act of 2013 for allegedly "using a telecommunication network to extort, threaten, obstruct, defame, disturb, inappropriately influence or intimidate."

Two recent cases have garnered a strong international responseresponses. The first case involves a former "child soldier," Aung Ko Htwe, who was arrested and convicted in March 2018 for violation of Section 505(b) of the Penal Code that makes it illegal to "cause fear or alarm to the public.". The second concerns the arrest and conviction on September 3, 2018, of two Reuters reporters, Kyaw Soe Oo and Wa Lone, for violating the Official Secrets Act of 1923.

The Case of Aung Ko Htwe

Aung Ko Htwe claims he was kidnapped and enlisted in the Burmese Army in 2005 at the age of 10.1617 In 2008, he deserted, but was soon arrested and charged with murder; he was convicted and sentenced to death, but his sentence was commuted to 10 years by Commander-in-Chief Senior General Min Aung Hlaing.1718 Following an August 10, 2017, interview with Radio Free Asia (RFA) in which he recounted his alleged kidnapping and enlistment, he was arrested and charged with violating Section 505(b) of the Penal Code that makes it illegal to "cause fear or alarm to the public." On March 28, 2018, Aung Ko Htwe was convicted and sentenced to two years imprisonment with hard labor. In addition, he was sentenced to six months in prison in February 2018 for criticizing the judge presiding over his trial. On October 30, 2018, he was acquitted of subsequent charges arising from his trial. He remains in prison, serving out the rest of his term.

The Case of Kyaw Soe Oo and Wa Lone

Kyaw Soe Oo and Wa Lone are reporters for Reuters who broke the story in February 2018 about the murder of 10 Rohingya by Tatmadaw soldiers in Inn Din village during the "clearance operations" in Rakhine State (see text box).1819 On December 17, 2017—two months before their story was published—they were arrested for allegedly violating the Official Secrets Act of 1923. The next day, Acting President Myint Swe granted Lieutenant Colonel Yu Naing the authority to press charges under the Official Secrets Act and Burma's Information Ministry announced their arrest and detention for "possessing important and secret government documents related to Rakhine State and security forces (with the intent) to send them to a foreign news agency."19

|

"Massacre in Myanmar": Kyaw Soe Oo and Wa Lone Story on Inn Din Reuters reporters Kyaw Soe Oo and Wa Lone conducted an extensive investigation into allegations that Tatmadaw soldiers had murdered 10 Rohingya from Inn Din village on September 2, 2017, during the "clearance operation" in Rakhine State. On February 8, 2018, their story (coauthored with Simon Lewis and Antoni Slodkowski) was published under the headline, "Massacre in Myanmar." The story recounted how Tatmadaw soldiers, local paramilitary police, and local Rakhine villagers killed 10 Rohingya men and buried their bodies in a mass grave outside the village of Inn Din. The reporters also obtained photos of the 10 men when they were under custody and tied up, and their 10 bodies in the mass grave. The Reuters story also described how members of the 33rd Light Infantry Battalion and the 8th Security Police Battalion, under orders, attacked and burned down Rohingya villages near Inn Din. The accounts describe indiscriminate shooting and killing of Rohingya, as well as the rape and sexual assault of Rohingya women and girls. On January 20, 2018, the Tatmadaw issued a statement, confirming portions of what Kyaw Soe Oo, Wa Lone, and their colleagues were preparing to report, and acknowledging that 10 Rohingya men were killed in the village. The statement also confirmed that Buddhist villagers attacked some of the men with swords. On April 10, 2018, the Tatmadaw convicted seven soldiers for their participation in the murders in Inn Din, sentencing them to seven years in prison. |

The trial of Kyaw Soe Oo and Wa Lone lasted over eight months and was full of conflicting and unusual testimony.2021 On February 6, 2018, a police lieutenant informed the court that he burned all his notes pertaining to the case. On April 20, 2018, prosecution witness Captain Moe Yan Naing testified that police Brigadier General Tin Ko Ko ordered him and other police officers to entrap the two reporters by giving them "secret documents" as part of a sting operation. After his testimony, Captain Moe Yan Naing was arrested and sentenced to one year in prison for violating the Police Disciplinary Act.21

On September 3, 2018, Kyaw Soe Oo and Wa Lone were convicted of violating the Official Secrets Act and sentenced to seven years in prison. The U.S. Embassy in Burma released the following statement:

Today's conviction of journalists Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo under the Official Secrets Act is deeply troubling for all who support press freedom and the transition toward democracy in Myanmar. The American people have long stood with the people of Myanmar in support of democracy, and we continue to support civilian rule and those advocating for freedom, reform, and human rights in Myanmar. The clear flaws in this case raise serious concerns about rule of law and judicial independence in Myanmar, and the reporters' conviction is a major setback to the Government of Myanmar's stated goal of expanding democratic freedoms. We urge the Government of Myanmar to release Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo immediately, and to end the arbitrary prosecution of journalists doing their jobs.22

Then-U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Nikki Haley also released a statement about the convictions, stating the following:

It is clear to all that the Burmese military has committed vast atrocities. In a free country, it is the duty of a responsible press to keep people informed and hold leaders accountable. The conviction of two journalists for doing their job is another terrible stain on the Burmese government. We will continue to call for their immediate and unconditional release.2324

Other governments, including the European Union and the United Kingdom, as well as many human rights organizations, also issued statements calling for the immediate release of Kyaw Soe Oo and Wa Lone.

On April 23, 2019, Burma's Supreme Court upheld the convictions and sentences imposed on Kyaw Soe Oo and Wa Lone. The following day, the State Department issued a press statement, indicating that the Court's decision "sends a profoundly negative signal about freedom of expression and the protection of journalists in Burma." The statement also urged Burma "to protect hard-earned freedoms, prevent further backsliding on recent democratic gains, and reunite these journalists with their families." Kyaw Soe Oo and Wa Lone were among the 6,520 prisoners granted a pardon on May 7, 2019. On April 30, 2018, peaceful protests were held in Myitkyina, the capital of Kachin State to demand that the Tatmadaw and the NLD-led government take steps to provide assistance to an estimated 2,000 people displaced by fighting between the Tatmadaw and the Kachin Independence Army (KIA). On September 3, 2018, Lum Zawng, Nang Pu, and Zau Jet were arrested for alleged violations of Section 500 of the Penal Code, defamation of the Burmese military. The three activists supposedly made inaccurate and derogatory statements about the Burmese military during the protests in Myitkyina and in a press conference the following day.

Definition of Political Prisoners

One factor complicating the end of political prisoners in Burma is a lack of agreement on the definition of a political prisoner. While the concept of political prisoner has a long history, there is no single international standard for defining political prisoners. Prisoners detained for political reasons are afforded some protection by international agreements, such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

The State Department's Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor considers someone a political prisoner if

- 1. the person is incarcerated in accordance with a law that is, on its face, illegitimate; the law may be illegitimate if the defined offense either impermissibly restricts the exercise of a human right; or is based on race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular group;

- 2. the person is incarcerated pursuant to a law that is on its face legitimate, where the incarceration is based on false charges where the underlying motivation is based on race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular group; or

- 3. the person is incarcerated for politically motivated acts, pursuant to a law that is on its face legitimate, but who receives unduly harsh and disproportionate treatment or punishment because of race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular group; this definition generally does not include those who, regardless of their motivation, have gone beyond advocacy and dissent to commit acts of violence.

24

25In applying this definition, the State Department recognizes that being accused of violent acts and committing violent acts are two different matters, and considers the circumstances pertaining to a particular person when determining whether she or he is to be considered a political prisoner. Following a human rights dialogue with the Thein Sein government in January 2015, the State Department issued a press release that included the statement, "The United States [government] expressed the need to adopt consensus definitions of 'prisoner of conscience' and 'political prisoner' as a basis to review cases."25

In Burma, one of the more critical issues in defining political prisoners is whether or not to include individuals who have been detained for their alleged association with Burma's ethnic-based militias or their associated political parties. Because these militias periodically have been involved in armed conflict with the Burmese military, some analysts exclude detainees allegedly associated with the militias from their estimates of Burma's political prisoners.

Ex-President Thein Sein consistently confined his definition to include only "prisoners of conscience," and generally used that phrase when discussing the issue. He repeatedly stated that individuals who have committed criminal acts are not considered "prisoners of conscience," and are expected to serve out their prison sentences. Similarly, Aung San Suu Kyi and Burma's military leaders prefer to restrict the definition of political prisoner to only include "prisoners of conscience." Some international groups, such as Amnesty International (AI), also use a narrower definition that emphasizes so-called "prisoners of conscience."2627

The AAPP(B) and Human Rights Watch (HRW) use a broader definition of political prisoner. The AAPP(B) defines a political prisoner as "anyone who is arrested because of his or her perceived or real involvement in or supporting role in opposition movements with peaceful or resistance means."2728 The AAPP(B) rejects the limitation of political prisoners to "prisoners of conscience" for several reasons. First, the AAPP(B) maintains that Burmese security forces frequently detain political dissidents with false allegations that they committed violent or nonpolitical crimes. Restricting the definition to "prisoners of conscience" would exclude many political prisoners. Second, the AAPP(B) maintains that the decision to participate in armed resistance against the government in Naypyidaw should be "viewed with the backdrop of violent crimes committed by the state, particularly against ethnic minorities."2829 In short, the AAPP(B) views armed struggle as a reasonable form of political opposition given the severity of the violence perpetrated by the Burmese military and police.

The Political Prisoners Review Committee (PPRC, also known as the Political Prisoner Scrutiny Committee), set up by former Burmese President Thein Sein, reportedly attempted to develop a consensus definition of political prisoners. Bo Kyi, the committee's AAPP(B) representative, told the press in May 2013 that the 19 members had agreed to a definition, but that the Thein Sein government did not formally adopt the definition.2930

On August 17 and 18, 2014, AAPP(B) and the FPPS held a workshop in Rangoon to discuss a common definition of political prisoners and to open a discussion with the Thein Sein government and Burma's Union Parliament on the topic.3031 Representatives of various Burmese organizations and political parties, as well as the International Committee of the Red Cross, attended the workshop. The attendees at the conference agreed to the following definition of political prisoner:

Anyone who is arrested, detained, or imprisoned for political reasons under political charges or wrongfully under criminal and civil charges because of his or her perceived or known active role, perceived or known supporting role, or in association with activities promoting freedom, justice, equality, human rights, and civil and political rights, including ethnic rights, is defined as a political prisoner.31

The adopted statement of the conferees further explained:

The above definition relates to anyone who is arrested, detained, or imprisoned because of his or her perceived or known active role, perceived or known supporting role, or in association with political activities (including armed resistance but excluding terrorist activities), in forming organizations, both individually and collectively, making public speeches, expressing beliefs, organizing or initiating movements through writing, publishing, or distributing documents, or participating in peaceful demonstrations to express dissent and denunciation against the stature and activities of both the Union and state level executive, legislative, judicial, or other administrative bodies established under the constitution or under any previously existing law.

Following the workshop, a Member of Parliament from Aung San Suu Kyi's National League for Democracy (NLD) reportedly said that the NLD would submit a proposed definition of political prisoner to the Union Parliament.32

Since the NLD has assumed power, different voices have called for establishing a legal definition of political prisoners. In their May 2016 report cited above, the AAPP(B) and FPPS recommended that the NLD-led government adopt an internationally recognized definition of political prisoners.3334 On June 2, 2016, Pe Than, an Arakan National Party (ANP) member of the Union Parliament's lower house, spoke on the chamber's floor in support of adopting legal definitions of "political prisoners" and "political offenses" to protect political activists.3435 Deputy Minister of Home Affairs General Aung Soe voiced his ministry's opposition to Pe Than's proposal, stating that providing special treatment to political prisoners would discriminate against other people arrested for alleged violations of the law.3536

In addition, human rights abuses by the government against two segments of Burmese society also have been raised in association with the issue of political prisoners. First, allegations of corruption among local Burmese officials are fairly common, with officials reportedly frequently using their official power to detain people on falsified charges in order to confiscate property (particularly land) or otherwise exact revenge on their opponents. In addition, officials have reportedly used provisions in old and new laws to arrest and detain people protesting alleged violations of their legal rights by those very same officials. These reported abuses of power by officials have been portrayed as creating a special group of "political prisoners." Second, past governments in Burma singled out the Rohingya, a predominately Muslim ethnic minority residing in northern Rakhine State along the border with Bangladesh, and allegedly subjected them to more extensive and invasive political repression, including restrictions on movement, employment, education, and marriage. The NLD-led government has done little to reverse the previous practice of discrimination against the Rohinyga.

Problematic Laws

Burma's 2008 Constitution provides for the continued authority of any laws promulgated prior to the adoption of the Constitution, unless they contravene provisions in the Constitution or are superseded by laws passed by the Union Parliament. As a result, many comparatively repressive laws, including some dating back to British colonial rule, remain in force in Burma. Over the last six years, the Union Parliament has repealed or amended some of the more problematic laws, but has also passed new laws that some observers view as being similarly repressive of human rights. Burma's security forces, and in particular, the Myanmar Police Force, have used these laws to suppress the voices of political opposition in Burma.

In its monthly report on political prisoners, the AAPP(B) includes information on which laws were allegedly violated. The following laws are those most frequently cited in the AAPP(B) monthly reports:

- The Unlawful Associations Act of 1908—Section 17(1) states that association with any organization that the President declares illegal is punishable by two to three years' imprisonment, along with a possible fine. Under Section 17(2), managing an unlawful association or promoting its meetings is subject to three to five years of imprisonment, and a possible fine. This law has been frequently used to declare ethnic armed organizations and their militias "unlawful associations." As of December 2016, at least 72 people were serving sentences for alleged violations of this act.

- The Telecommunications Law of 2013—Section 66(d) subjects anyone found "[e]xtorting, coercing, restraining wrongfully, defaming, disturbing, causing undue influence or threatening to any person by using any Telecommunications Network" to up to three years in prison and/or a fine. This law is being used to arrest and try political commentators and journalists who criticize government policy, government officials, or the Tatmadaw on social media. The AAPP(B) has compiled a list of 37 Section 66(d) cases since October 2015, including 10 convictions.

- The Right to Peaceful Assembly and Peaceful Procession Act of 2011 (as amended in 2016)—The law places restrictions on the freedom of assembly and expression inconsistent international human rights laws and standards.

3637 Violators of the law are subject to up to two years in prison and/or a fine. This law has reportedly been used to arrest and try people protesting against alleged illegal land confiscations by local officials and the Tatmadaw, as well as individuals rallying in opposition to other actions by the Burmese government and the military. On July 15, 2015, the U.S.embassyEmbassy in Rangoon issued a statement indicating, "The United States is concerned over continued reports or arrests and excessive prison terms handed down to peaceful protesters under Article 18 of the Peace Assembly and Processions Act."37

38

3839 The commission recommended abolishing the Emergency Provisions Act of 1950 (which made it illegal to engage in activities that hindered the ability of the government or the military to perform their duties) and Section 505(b) of the Penal Code (which makes it illegal to circulate, make, or publish any statement, rumor, or report "with intent to cause, or which is likely to cause, fear or alarm to the public or to any section of the public whereby any person may be induced to commit an offence against the State or against the public tranquility"), as well as amend Article 18 of the Peace Assembly and Processions Act.

In January 2016, the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), a federation of over 180 international human rights organizations, called on the incoming Union Parliament to repeal or amend several laws enacted by the outgoing Union Parliament. The laws identified by FIDH included the Right to Peaceful Assembly and Peaceful Procession Act of 2011; the Telecommunications Act of 2013; the Printing and Publications Act of 2014; the Media Act of 2014; and the four so-called "Race and Religion Protection Laws" of 2015 (the Interfaith Marriage Law, the Monogamy Law, the Population Control Law, and the Religious Conversion Law), which are seen as discriminating against Burma's Muslim population. Human Rights Watch issued a report in 2016, entitled "They Can Arrest You at Any Time: The Criminalization of Peaceful Expression in Burma," that also cited these laws as tools of political oppression, as well as several others, including the Electronic Transactions Act of 2004; the Official Secrets Act of 1923; and various sections of the Penal Code (Sections 124A, 130B, 141-147, 153A, 295A, 298, 503, 405, 505(b), 505(c), and 509).39

Since taking office in January 2016, the NLD-led Union Parliament has made some efforts to repeal or amend a few of the problematic laws. In May 2016, the Union Parliament revoked the State Protection Act of 1975, which allowed the government to declare a State of Emergency and to suspend citizens' basic rights.4041 In October 2016, it repealed the Emergency Provisions Act of 1950, which effectively prohibited criticism of the Tatmadaw or the government.4142 In December 2016, proposals were submitted to amend Section 66(d) of the Telecommunications Act of 2013, but they have not been approved.

Civilian Government Authority over Criminal Cases

Under Burma's 2008 constitution, the President has limited authority over the arrest and detention of people for alleged criminal activity; the Commander-in-Chief of Defence Services controls the security forces that make arrests. In part as a result, people in Burma continue to be arrested and convicted for their political activities. The President, however, can direct that pending cases be dropped, as well as grant pardons and amnesties once people have been convicted.

Burma's 2008 constitution stipulates "All the armed forces in the Union shall be under the command of the Defence Services" (Article 338) and "The Defence Services shall lead in safeguarding the Union against all internal and external dangers" (Article 339). The Commander-in-Chief is to be appointed by the President, "with the proposal and approval of the National Defence and Security Council" (Article 342).4243 Article 20(c) states, "The Commander-in-Chief of the Defence Services is the Supreme Commander of all armed forces."

Burma's Defence Services includes the Myanmar Armed Forces (or Tatmadaw), the Border Guard Forces, and the Myanmar Police Force.4344 The Myanmar Armed Forces and the Border Guard Forces are part of the Ministry for Defence; the Myanmar Police Force are part of the Ministry for Home Affairs. Article 232(b)(ii) of the 2008 constitution requires the President "obtain a list of suitable Defence Services personnel nominated by the Commander-in-Chief of the Defence Services for Ministries of Defence, Home Affairs and Border Affairs," thereby requiring that those Ministers be active military personnel and giving the Commander-in-Chief authority over who is selected as Minister of Defence, Home Affairs, and Border Affairs. As a result, the Commander-in-Chief of Defence Services has authority over Burma's security forces and, by extension, over the arrest and detention of persons who allegedly have violated the law.

Once arrests have been made, the cases are directed to Burma's attorney general, who is appointed by the president (subject to the approval of the Union Parliament) and reports directly to the president. Public prosecutors, appointed at the local level and under the attorney general's authority, are responsible for prosecuting criminal cases. As such, the president does have the authority to direct the attorney general and the public prosecutors to drop charges considered political in nature. In April 2016, State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi exercised such authority to secure the release of over 100 people being detained for participation in peaceful protests.

Article 204 of the constitution gives the president the power to grant pardons and amnesties (in accord with the recommendation of the National Defence and Security Council). In addition, Section 401(1) of Burma's Code of Criminal Procedures states the following:

When any person has been sentenced to punishment for an offence, the President of the Union may at any time, without conditions or upon any conditions which the person sentenced accepts, suspend the execution of his sentence or remit the whole or any part of the punishment to which he has been sentenced.

The authority to grant pardons and amnesties was used several times by former Presidents Thein Sein and Htin Kyaw, and has been used by current President Win Myint.

Pending Legislation

The Burma Political Prisoners Assistance Act (BPPAA, H.R. 2327) was introduced on April 15, 2019, by Representatives Andy Levin and Ann Wagner. It would call for immediate release of Kyaw Soe Oo, Lum Zawng, Nang Pu,Wa Lone, and Zau Jet (all five have been released or granted pardons since the bill's introduction). The legislation would also state that it is U.S. policy that (1) all prisoners of conscience and political prisoners in Burma be "unconditionally and immediately released"; (2) the Administration and the Department of State "should use all their diplomatic tools" to ensure such a release occurs; and (3) the NLD-led government should "repeal or amend all laws that violate the rights to freedom of expression, peaceful assembly, or association." In addition, the BPPAA would require that the Secretary of State provide assistance to civil society organizations in Burma that "work to secure the release of prisoners of conscience and political prisoners in Burma," as well as assistance to current and former prisoners of conscience and political prisoners in Burma. That assistance shall include: The BPPAA would also include definitions for prisoners of conscience and political prisoners. The legislation's definition of prisoners of conscience is similar to that used by Amnesty International. It would define political prisoners as any person: who is arrested, detained, or imprisoned for political reasons under political charges or wrongfully under criminal and civil charges because of his or her perceived or known active role in, perceived or known supporting role in, or perceived or known association with activities promoting freedom, justice, equality, human rights, or civil and political rights, including ethnic rights..

Issues for U.S. Policy

Some of the options that Congress may consider to address issues of political imprisonment in Burma include the following:

- Providing technical and other forms of assistance to the Union Parliament and the Ministry of Justice in identifying and revising those laws that have been or could be used to arrest and prosecute people for political reasons;

- Pressuring the NLD-led government to reevaluate and consider repealing laws or regulations that declare any of the ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) illegal under the Unlawful Associations Act of 1908;

- Supporting the reestablishment of a Political Prisoners Review Committee or a similar body to identify alleged political prisoners and develop an official definition of political prisoners;

- Imposing suitable restrictions on relations with Burma until all political prisoners have been unconditionally released;

- Conditioning the provision of certain types of assistance to the NLD-led government and/or the Tatmadaw contingent on the adoption of an official definition of political prisoner, and on the release of political prisoners;

- Imposing suitable restrictions on relations with Burma until sufficient reforms of Burma's security forces, including the Myanmar Police Force, have been undertaken to preclude or reduce the likelihood people will be arrested or prosecuted as political prisoners; and

- Including the absence of political prisoners in Burma as a criteria for determining that a democratic civilian government that respects human rights and civil liberties has been established in Burma, and that certain restrictions on bilateral relations can be removed.

The presence of political prisoners in Burma is only one of several possible issues that Congress may consider when examining U.S. policy toward Burma. Other key issues may be as follows:

- The Low-

gradeGrade Civil War: Burma has endured a low-grade civil war between the Tatmadaw and up to 20 ethnic armed organizations for over 50 years.4445 Aung San Suu Kyi has made the peace process a high priority for the NLD-led government, but the three "21st Century Panglong Peace Conferences" (held on August 31-September 3, 2016, May 24-29, 2017, and July 11-16, 2018, respectively) have made little progress toward ending the long-standing conflict.According to Burma News International (BNI), fighting between the Tatmadaw and several ethnic armed organizations has increased since the first peace conferences was held.45Tatmadaw Commander-in-Chief Min Aung Hlaing announced a unilateral ceasefire in eastern Burma for the first half of 2019, but periodic fighting between the Tatmadaw and several EAOs continues to be reported. - Violence in Rakhine State and the Rohingya Refugee Crisis: On August 25, 2017, the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) attacked 30 security outposts along Burma's border with Bangladesh. The Tatmadaw responded with a "clearance operation" that resulted in the flight of over 700,000 Rohingya into Bangladesh.46 A United Nations Fact Finding Mission on Myanmar has recommended that the United Nations Security Council refer six Tatmadaw senior officers to the International Criminal Court for investigation and possible prosecution for genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes for serious human rights abuses committed during the clearance operations.47 In December 2018, the Arakan Army began a campaign to establish bases in northern Rakhine State. The Tatmadaw responded by deploying heavily-armed troops into the region. Frequent fighting between the Arakan Army and the Tatmadaw continues to occur, complicating any plans of the safe and voluntary return of the Rohingya. Relations between the two major ethnic minorities residing in Rakhine State—the Rakhine (also known as Arakan) and the Rohingya—have been problematic for decades. In 1982, Burma's military junta stripped the Rohingya of their citizenship, and began portraying the vast majority of them as illegal immigrants from Bangladesh and India.48 Violent unrest broke out in Rakhine State in 2012, resulting in the deaths of at least 57 Rohingya and 31 Rakhine, and the displacement of an estimated 90,000 people, mostly Rohingya.49 In October 2016, after a group of assailants attacked three police outposts, the Tatmadaw began a "clearance operation" in northern Rakhine State that, according to the U.N. Office of High Commissioner of Human Rights (OHCHR), resulted in the murder, enforced disappearance, torture, rape, arbitrary detention, and forced deportation of hundreds of Rohingya.50

- Constitutional and Legal Reform: During the parliamentary campaign, the NLD stated that it would seek to implement both constitutional and legal reforms aimed at establishing a more democratic government and protecting the human rights of the people of Burma. Some analysts note that, since taking office in April 2016, the NLD has made little progress on either campaign pledge.

|

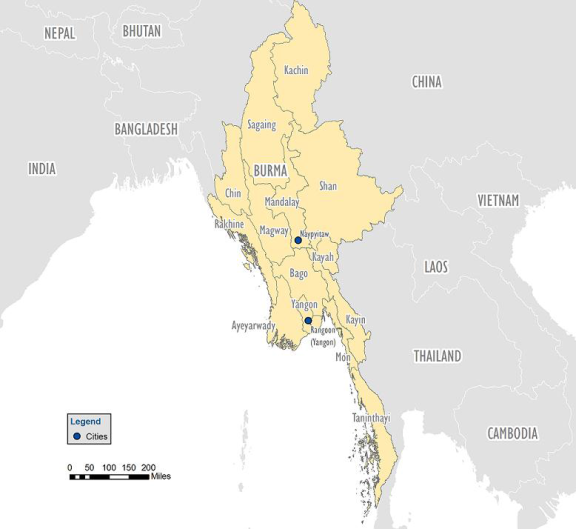

Showing States and Regions |

|

|

Source: CRS . |

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

According to the country's 2008 constitution, its official name is "the Republic of the Union of Myanmar," or "Myanmar." The U.S. government continues to officially refer to the nation as "the Union of Burma," or "Burma," but uses "Myanmar" inside the country and at multilateral fora where the host refers to the nation as "Myanmar." |

|

| 2. |

Between 1989 and 2010, Aung San Suu Kyi was under house arrest or in prison for 15 of the 21 years, including a short stay in Insein Prison following an assassination attempt in the town of Depayin. For more about her years as a political prisoner, see Human Rights Watch, Burma: Chronology of Aung San Suu Kyi's Detention, November 13, 2010. |

|

| 3. |

Section 138 of the Customs and Trade Act of 1990 (P.L. 101-382) requires the President to "impose such economic sanctions upon Burma as the President determines to be appropriate until certain conditions are met, including "Prisoners held for political reasons in Burma have been released." The Burmese Freedom and Democracy Act of 2003 (P.L. 108-61) stipulates as one condition for the termination of the act's sanctions, "The SPDC has made measurable and substantial progress toward implementing a democratic government, including—(i) releasing all political prisoners; …" The Tom Lantos Block Burmese JADE (Junta's Anti-Democratic Efforts) Act of 2008 (JADE Act; P.L. 110-286) sets as one of the conditions for the termination of its sanctions that "the President determines and certifies to the appropriate congressional committees that the SPDC has—(1) Unconditionally released all political prisoners, including Aung San Suu Kyi and other members of the National League for Democracy; …" |

|

| 4. |

For example, in Executive Order 13742 issued on October 7, 2016, which waived the economic sanctions imposed by Section 5(b) of the JADE Act and terminated and revoked Executive Orders 13047, 13310, 13448, 13464, 13619, and 13651, President Obama mentioned "the release of many political prisoners" among the evidence of "Burma's substantial advances to promote democracy." Similarly, Presidential Determination No. 2017-04, which terminated restrictions on bilateral assistance to Burma contained in Section 570(1) of the Foreign Operations, Export Financing, and Related Programs Appropriations Act, 1997 (P.L. 104-208), President Obama citied "the new civilian [sic] government released 63 political prisoners and dropped charges against almost 200 individuals facing trial on political grounds" as evidence of "measurable and substantial progress in improving human rights practices and implementing democratic government," as required by that act. |

|

| 5. |

U.S. Mission in Geneva, "Statement by the Delegation of the United States of America as Delivered by William J. Mozdzierz," press release, March 13, 2017, https://geneva.usmission.gov/2017/03/13/interactive-dialogue-with-the-special-rapporteur-on-the-situation-of-human-rights-in-myanmar/. |

|

| 6. |

For information about Burma's 2015 parliamentary elections and the NLD's landslide victory, see CRS Report R44436, Burma's 2015 Parliamentary Elections: Issues for Congress, by Michael F. Martin. |

|

| 7. |

Assistance Association of Political Prisoners (Burma), |

|

| 8. |

Ye Mon, "NLD Pledges No More Political Prisoners," Myanmar Times, January 6, 2016. |

|

| 9. |

Ibid. |

|

| 10. |

The newly elected members of the Union Parliament took office in January 2016; President Htin Kyaw and State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi were appointed to their offices by the Union Parliament in March 2016, and were sworn into office in April 2016. |

|

| 11. |

President Office, Republic of the Union of Myanmar, "State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi to strive for the granting of presidential pardon to political prisoners, activists, students," press release, April 11, 2016. |

|

| 12. |

"Myanmar President Pardons 83 Political Prisoners; Official," AFP, April 18, 2016. |

|

| 13. |

"NLD Government has Released 457 Political Prisoners," Democratic Voice of Burma, August 18, 2016. |

|

| 14. |

"President Grants General Amnesty for 8541 Prisoners," Eleven Myanmar, April 18, 2018. |

|

| 15. |

Assistance Association of Political Prisoners (Burma), April Chronology 2018, May 15, 2018. |

|

| 16. |

Nyein Nyein, "Latest Presidential Amnesty Includes Dozens of EAO Members, Accused Associates," Irrawaddy, May 7, 2019.

|

|

|

Aung Kyaw Min, "Former Child Soldier Faces Court for Talking to Media," Myanmar Times, September 4, 2017. |

||

|

Kyaw Soe Oo, Wa Lone, and Simon Lewis, et al., "Massacre in Myanmar," Reuters, February 8, 2018. |

||

|

Ministry of Information, "Two Reporters, Two Policemen Arrested in Yangon," press release, December 17, 2017. |

||

|

"Reuters Case Timeline," Irrawaddy, September 3, 2018. |

||

|

Naw Betty Han, "Whistle-Blower Police Officer Gets One-Year Jail Sentence," Myanmar Times, May 1, 2018. |

||

|

U.S. Embassy in Burma, "U.S. Embassy Statement on Conviction of Reuters Reporters Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo," press release, September 3, 2018. |

||

|

United States Mission to the United Nations, "Ambassador Haley on the Announcement of a Guilty Verdict in the Trial of Reuters Journalists in Burma," press release, September 3, 2018. |

||

|

Definition provided to CRS by the State Department, July 2016. |

||

|

State Department, "Myanmar and United States Conclude Successful Second Human Rights Dialogue," press release, January 16, 2015. |

||

|

Amnesty International's definition is "people who have been jailed because of their political, religious or other conscientiously-held beliefs, ethnic origin, sex, color, language, national or social origin, economic status, birth, sexual orientation or other status, provided that they have neither used nor advocated violence." (http://www.amnestyusa.org/our-work/issues/prisoners-and-people-at-risk/prisoners-of-conscience). |

||

|

AAPP(B), "The Recognition of Political Prisoners: Essential to Democratic and National Reconciliation Process," press release, November 9, 2011. |

||

|

AAPP(B), "The Recognition of Political Prisoners: Essential to Democratic and National Reconciliation Process," press release, November 9, 2011. |

||

|

"Burma Releases Political Prisoners Ahead of US State Visit," Irrawaddy, May 17, 2013. |

||

|

"Myanmar Still Seeks Definition of Political Prisoner," Eleven Myanmar, August 18, 2014. |

||

|

Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (Burma), AAPP & FPPS Press Release About the Definition of a Political Prisoner, September 2, 2014, http://aappb.org/2014/09/aapp-fpps-press-release-about-the-definition-of-a-political-prisoner/. |

||

|

"NLD Moving to Recognise Myanmar's 'Political Prisoners,'" Eleven Myanmar, August 20, 2014. |

||

|

AAPP(B) and FPPS, "After Release I Had to Restart My Life from the Beginning," May 25, 2016, http://aappb.org/2016/05/after-release-i-had-to-restart-my-life-from-the-beginning-the-experiences-of-ex-political-prisoners-in-burma-and-challenges-to-reintegration/. |

||

|

"Union Government Urged to Adopt Political Prisoner Definition," Global New Light of Myanmar, June 3, 2016. |

||

|

Tin Htet Paing, "Calls to Legally Define Political Prisoners Rebutted in Parliament," Irrawaddy, June 2, 2016; |

||

|

For more information on how the law violates international human rights laws and standards, see Human Rights Watch, Burma: Proposed Assembly Law Falls Short, May 27, 2016. |

||

|

U.S. Embassy, Rangoon, "Statement," press release, July 15, 2015. |

||

|

San Yamin Aung, "Legal Commission Recommends Scrapping 142 Laws," Irrawaddy, April 8, 2016. |

||

|

Human Rights Watch, They Can Arrest You at Any Time: The Criminalization of Peaceful Expression in Burma, June 2016. |

||

|

Htoo Thant, "Hluttas Revoke Oppressive State Protection Law," Myanmar Times, May 26, 2016. |

||

|

For example, Section 5(b) made it illegal "to depreciate, pervert, hinder, restrain, or vandalise the loyalty, enthusiasm, acquiescence, health, training, or performance of duties of the army organisations of the Union or of civil servants in a way that would induce their respect of the government to be diminished, or to disobey rules, or to be disloyal to the government." Wai Moe, "Myanmar Repeals 1950 Law Long Used to Silence Dissidents," New York Times, October 5, 2016. |

||

|

The National Defence and Security Council includes the President, two Vice Presidents, the Speakers of each chamber of the Union Parliament, the Commander-in-Chief of Defence Services, the Deputy Commander-in-Chief of Defence Services, and the Minister for Defence, the Minister for Border Affairs, the Minister for Foreign Affairs, and the Minister for Home Affairs. |

||

|

In addition, there are various local militias organized and supported by the Tatmadaw. For more about the militias of Burma, see John Buchanan, Militias in Myanmar, Asia Foundation, Policy Dialogue Brief #13, July 2016. |

||

|

For more about Burma's civil war and its current peace process, see CRS In Focus |

||

| 45. |

"Conflicts Increase in Ethnic Areas After 21st Century Panglong Conference, Peace Survey Points Out," Burma News International, January 30, 2017. |

|

| 46. |

For more information, see CRS Report R45016, The Rohingya Crises in Bangladesh and Burma, coordinated by Michael F. Martin. |

|

| 47. |

See CRS In Focus IF10970, U.N. Report Recommends Burmese Military Leaders Be Investigated and Prosecuted for Possible Genocide, by Michael F. Martin, Matthew C. Weed, and Colin Willett. |

|

| 48. |

As part of the effort to delegitimize the Rohingya, the military junta began referring to them as "Bengalis," a reference to their alleged origin from Bangladesh and India. |

|

| 49. |

For a study of the 2012 Rakhine riots and their aftermath, see Human Rights Watch, All You Can Do |

|

| 50. |

U.N. High Commissioner of Human Rights, Interviews with Rohingyas Fleeing from Myanmar |