Iraq: Issues in the 115th Congress

Changes from March 5, 2018 to October 4, 2018

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Iraq: In Brief

Contents

- Overview

- Developments in 2017 and 2018

- Iraq Declares Victory against the Islamic State, Pursues Fighters

- Uncertainty and Confrontation in Iraq's Disputed Territories

- May 2018 Elections

- Popular Mobilization Forces and Iraqi Security Forces

- The Kurdistan Region and Relations with Baghdad

- Economic and Fiscal Challenges Continue

- Humanitarian Issues and Stabilization

- Humanitarian Conditions

- Stabilization and Reconstruction

PotentialIssuesforin the 115th Congress- U.S. Military Operations

- U.S. Foreign Assistance

- Legislation in the 115th Congress

- Outlook

Figures

Overview

Summary

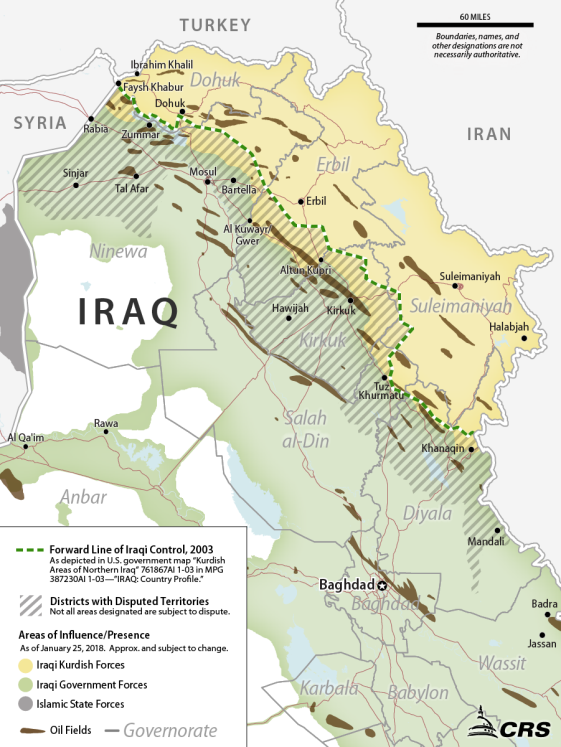

Iraq's government declared military victory against the terrorist insurgents of the Islamic State grouporganization (IS, aka ISIS/ISIL) in December 2017, but counterinsurgency and counterterrorism operations against the group are ongoing. Iraqis are shiftinginsurgent attacks by remaining IS fighters threaten Iraqis as they shift their attention toward recovery and the country's political future. Security conditions have improved (Figure 1) but remain fluid, andsince the Islamic State's control of territory was disrupted, but IS fighters are active in some areas and security conditions are fluid.

Meanwhile, daunting resettlement, reconstruction, and reform needs occupy citizens and decisionmakers. National legislative elections are scheduled for May 12, 2018, and campaigning reflects issues stemming from the 2014-2017 conflict with the Islamic State as well as a range of preexisting internal disputes and governance challenges. Ethnic, religious, regional, and tribal identities remain politically relevant, as do partisanship, personal rivalries, economic disparities, and natural resource imbalances. Iraq's neighbors and other outsiders continue to pursue their interests in the country, at times cooperatively and at times in competition.

Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al Abadi is seeking reelection in May, but rivals from other factions and movements are running as competitors. While Iraq's major ethnic and religious constituencies are each politically diverse, many Iraqis advance similar demands for improved security, government effectiveness, and economic opportunity. Prime Minister Abadi and other politicians increasingly employ cross-sectarian political and economic narratives, but identity-driven politics continue to influence developments across the country.

National legislative elections were held in May 2018, but results were not certified until August, delaying the formal start of required steps to form the next government. Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al Abadi sought reelection, but his electoral list's third-place showing and lack of internal cohesion undermined his chances for a second term. On October 2, Iraq's Council of Representatives (COR) chose former Kurdistan Regional Government Prime Minister and former Iraqi Deputy Prime Minister Barham Salih as Iraq's President. Salih, in turn, named former Oil Minister Adel Abd al Mahdi as Prime Minister-designate and directed him to assemble a slate of cabinet officials for COR approval within 30 days. Paramilitary forces have grown stronger and more numerous since 2014, and have yet to be fully integrated into national security institutions. Some figures associated with the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) that were organized to fight the Islamic State participated in the 2018 election campaign and won seats in the Council of Representatives, including individuals with ties to Iran. Iraqi politicians have increasingly employed cross-sectarian political and economic narratives in an attempt to appeal to disaffected citizens, but identity-driven politics continue to influence developments. Iraq's neighbors and other outsiders, including the United States, are pursuing their respective interests in Iraq, at times in competition. The Kurdistan Region of northern Iraq (KRI) enjoys considerable administrative autonomy under the terms of Iraq's 2005 constitution, and the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) held legislative elections on September 30, 2018. The KRG had held a controversial advisory referendum on independence in September 2017, amplifying political tensions with the national government, which moved to reassert security control of disputed areas that had been secured by Kurdish forces after the Islamic State's mid-2014 advance. Iraqi and Kurdish security forces remain deployed across from each other along contested lines of control, while their respective leaders are engaged in negotiations over a host of sensitive issues. In general, U.S. engagement with Iraqis since 2011 has sought to reinforce Iraq's unifying tendencies and avoid divisive outcomes. At the same time, successive U.S. Administrations have sought to keep U.S. involvement and investment minimal relative to the 2003-2011 era, pursuing U.S. interests through partnership with various entities in Iraq and the development of those partners' capabilities—rather than through extensive deployment of U.S. military forces. The Trump Administration has sustained a cooperative relationship with the Iraqi government and plans to continue security training for Iraqi security forces. To date, the 115th Congress has appropriated funds for U.S. military operations against the Islamic State and for security assistance, humanitarian relief, and foreign aid for Iraq. For background on Iraq and its relations with the United States, see CRS Report R45025, Iraq: Background and U.S. Policy. National legislative elections were held in May 2018, but results were not certified until August, delaying the formal start of required steps to form the next government. Turnout was low relative to past national elections, and campaigning reflected issues stemming from the 2014-2017 conflict with the Islamic State as well as preexisting internal disputes and governance challenges. Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al Abadi sought reelection, but his electoral list's third-place showing and lack of internal cohesion undermined his chances for a second term. He is serving in a caretaker capacity as government-formation negotiations continue. In September 2018, a statement from the office of leading Shia religious leader Grand Ayatollah Ali al Sistani called for political forces to choose a prime minister from beyond the ranks of current or former officials. Nevertheless, on October 2, Iraq's Council of Representatives chose former Kurdistan Regional Government Prime Minister and former Iraqi Deputy Prime Minister Barham Salih as Iraq's President. Salih, in turn, named former Oil Minister Adel Abd al Mahdi as Prime Minister-designate and directed him to assemble a slate of cabinet officials for approval by the Council of Representatives (COR). Paramilitary forces have grown stronger and more numerous since 2014, and have yet to be fully integrated into national security institutions. Some figures associated with the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) militias that were organized to fight the Islamic State participated in the 2018 election campaign and won seats in the COR, including individuals with ties to Iran. Since the ouster of Saddam Hussein in 2003, Iraq's Shia Arab majority has exercised new power in concert with the Sunni Arab and Kurdish minorities. Despite ethnic and religious diversity and political differences, many Iraqis advance similar demands for improved security, government effectiveness, and economic opportunity. Large, volatile protests in southern Iraq during August and September 2018 highlighted some citizens' outrage with poor service delivery and corruption. Iraqi politicians have increasingly employed cross-sectarian political and economic narratives in an attempt to appeal to disaffected citizens, but identity-driven politics continue to influence developments across the country. Iraq's neighbors and other outsiders, including the United States, are pursuing their respective interests in the country, at times in competition.The Kurdistan Region of northern Iraq (KRI) enjoys considerable administrative autonomy under the terms of Iraq's 2005 constitution, and the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) expects to hold legislative and presidential elections sometime in 2018. Kurdish voters overwhelmingly favored independence in a controversial KRG advisory referendum on September 25,leaders. Internally displaced Iraqis are returning home in greater numbers, but stabilization and reconstruction needs in liberated areas are extensive. An estimated 1.9 million Iraqis remain as internally displaced persons (IDPs), and Iraqi authorities have identified $88 billion in reconstruction needs over the next decade. Large protests in southern Iraq during August and September 2018 highlighted some citizens' outrage with poor service delivery and corruption.

Overview

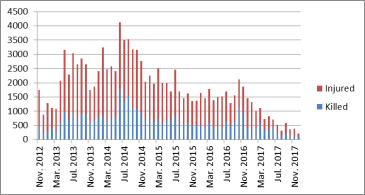

Iraq's government declared military victory against the Islamic State organization (IS, aka ISIS/ISIL) in December 2017, but insurgent attacks by remaining IS fighters threaten Iraqis as they shift their attention toward recovery and the country's political future. Security conditions have improved since the Islamic State's control of territory was disrupted (Figure 1 and Figure 2), but IS fighters are active in some areas of the country and security conditions are fluid. Meanwhile, daunting resettlement, reconstruction, and reform needs occupy citizens and leaders. Ethnic, religious, regional, and tribal identities remain politically relevant in Iraq, as do partisanship, personal rivalries, economic disparities, and natural resource imbalances.

Internally displaced Iraqis are returning home in greater numbers, but stabilization and reconstruction needs in areas liberated from the Islamic State are extensive. As of March 2018, an estimated 2.3An estimated 1.9 million Iraqis remain as internally displaced persons (IDPs), and Iraqi authorities have identified more than $88 billion in reconstruction needs. Paramilitary forces have grown stronger and more numerous since 2014, but have yet to be fully integrated into national security institutions. Some figures associated with the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) militias that were organized to fight the Islamic State are participating in the 2018 election campaign and may cooperate with or challenge Prime Minister Abadi, including individuals with ties to Iran.

In general, U.S. engagement with Iraqis since 2011 has sought to reinforce Iraq's unifying tendencies and avoid divisive outcomes. At the same time, successive U.S. Administrations have sought to keep U.S. involvement and investment minimal relative to the 2003-2011 era, pursuing U.S. interests through partnership with various entities in Iraq and the development of those partners' capabilities—rather than through extensive deployment of U.S. military forces. U.S. economic assistance bolsters Iraq's ability to attract lending support and seeks to improve the Iraqiis aimed at improving the government's effectiveness and public financial management. The United States is the leading provider of humanitarian assistance to Iraq and also supports post-IS stabilization activities across the country through grants to United Nations agencies and other entities.

The Trump Administration has sustained a cooperative relationship with the Iraqi government and has requested funding to support Iraq's stabilization and continue security training for Iraqi forces beyond the completion of major military operations against the Islamic State. The nature and extentsecurity forces. The size and missions of the U.S. military presence and mission in Iraq is evolving in 2018 as conditions on the ground change andin Iraq has evolved as conditions on the ground have changed since 2017 and could change further if newly elected Iraqi officials make their training needs and requests clearer.

To date, the 115th Congress has appropriated funds to continue U.S. military operations against the Islamic State and to provide security assistance, humanitarian relief, and foreign aid for Iraq. Appropriations and authorization billslegislation enacted or under consideration for FY2018FY2019 would largely continue U.S. policies and programs on current terms. For background on Iraq and its relations with the United States, see CRS Report R45025, Iraq: Background and U.S. Policy.

|

Figure 1. Estimated Iraqi Civilian Casualties from Conflict and Terrorism |

|

|

Source: United Nations Assistance Mission in Iraq. Some months lack data from some governorates. |

Developments in 2017 and 2018

Iraq Declares Victory against the Islamic State, Pursues Fighters

In July 2017, Prime Minister Haider al Abadi visited Mosul to mark the completion of major combat operations there against Islamic State forces, which had taken the city in June 2014. The defeat of IS forces in Mosul left the group with isolated areas of control in Tal Afar in Ninewa governorate, near Hawijah in Kirkuk and adjacent governorates, and in far western Anbar governorate. Iraqi forces retook Tal Afar and Hawijah in late summer 2017, and launched new operations in Anbar in October amid tensions elsewhere in territories disputed between the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) and national authorities. On December 9, 2017, Iraqi officials announced victory against the Islamic State and declared a national holiday.

Although the Islamic State's control over distinct territories in Iraq has now virtually ended, the U.S. intelligence community told Congress in February 2018 that the Islamic State "has started—and probably will maintain—a robust insurgency in Iraq and Syria as part of a long-term strategy to ultimately enable the reemergence of its so-called caliphate."1 Iraqi security forces continue to operate against IS fighters in areas of Anbar, Ninewa, Salah al Din, Diyala, and Kirkuk governorates and routinely announce anti-IS strikes and seizures of explosives and weapons.

|

|

|

Area: 438,317 sq. km (slightly more than three times the size of New York State) Population: 39.192 million (July 2017 estimate), ~59% are 24 years of age or under Internally Displaced Persons: Religions: Muslim 99% (55-60% Shia, 40% Sunni), Christian <0.1%, Yazidi <0.1% Ethnic Groups: Arab 75-80%; Kurdish 15-20%; Turkmen, Assyrian, Shabak, Yazidi, other ~5%. Gross Domestic Product [GDP; growth rate Budget (revenues; expenditure; balance): $77.42 billion, $88 billion, -$10.58 billion (2018 est.) Percentage of Revenue from Oil Exports: 87% (June 2017 est.) Current Account Balance: Oil and natural gas reserves: 142.5 billion barrels (2017 est., fifth largest); 3.158 trillion cubic meters (2017 est.) External Debt: $73.43 billion (2017 est.) Foreign Reserves: ~$47.02 billion (December 2017 est.) |

Sources: Graphic created by CRS using data from U.S. State Department and Esri. Country data from CIA, The World Factbook, In July 2017, Prime Minister Haider al Abadi visited Mosul to mark the completion of major combat operations there against the Islamic State forces that had taken the city in June 2014. Iraqi forces subsequently retook the cities of Tal Afar and Hawijah, and launched operations in Anbar Governorate in October amid tensions elsewhere in territories disputed between the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) and national authorities. On December 9, 2017, Iraqi officials announced victory against the Islamic State and declared a national holiday. Although the Islamic State's exclusive control over distinct territories in Iraq has now ended, the U.S. intelligence community told Congress in February 2018 that the Islamic State "has started—and probably will maintain—a robust insurgency in Iraq and Syria as part of a long-term strategy to ultimately enable the reemergence of its so-called caliphate."1

Source: Congressional Research Service using IHS Markit Conflict Monitor, ESRI, and U.S. State Department data. As of October 2018, Iraqi security operations are ongoing in Anbar, Ninewa, Diyala, and Salah al Din against IS fighters. These operations are intended to disrupt IS fighters' efforts to reestablish themselves and keep them separated from population centers. Iraqi officials warn of IS efforts to use remaining safe havens in Syria to support infiltration of Iraq. Press reports and U.S. government reports describe continuing IS attacks, particularly in rural areas of governorates the group formerly controlled. Independent analysts describe dynamics in these areas in which IS fighters threaten, intimidate, and kill citizens in areas at night or where Iraq's national security forces are absent.2 In some areas, new displacement is occurring as civilians flee IS attacks. Iraq's 2018 National Legislative Election Seats won by Coalition/Party Coalition/Party Seats Won Sa'irun 54 Fatah 48 Nasr 42 Kurdistan Democratic Party 25 State of Law 25 Wataniya 21 Hikma 19 Patriotic Union of Kurdistan 18 Qarar 14 Others 63 Source: Iraq Independent High Electoral Commission. On May 12, 2018, Iraqi voters went to the polls to choose national legislators for four-year terms in the 329-seat Council of Representatives, Iraq's unicameral legislature. Turnout was lower in the 2018 COR election than in past national elections, and reported irregularities led to a months-long recount effort that delayed certification of the results until August. Nevertheless, since May, the results have informed Iraqi negotiations aimed at forming the largest bloc within the COR—the parliamentary majority charged with proposing a prime minister and new Iraqi cabinet. Senior officials from Iran and the United States are monitoring the talks closely and consulting with leading Iraqi figures. Former prime minister Nouri al Maliki's State of Law coalition, Ammar al Hakim's Hikma (Wisdom) list, and Iyad Allawi's Wataniya (National) list also won significant blocs of seats. Among Kurdish parties, the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) won the most seats, and smaller opposition lists protested alleged irregularities. Escalating frustration in southern Iraq with unemployment, corruption, and electricity and water shortages has driven widespread popular unrest since the May election, amplified in some instances by citizens' anger about heavy-handed responses by security forces and militia groups. Dissatisfaction exploded in the southern province of Basra during August and September, culminating in several days and nights of mass demonstrations and the burning by protestors of the Iranian consulate in Basra and the offices of many leading political groups and militia movements. Reports from Basra in the weeks since the unrest suggest that some protestors have been intimidated or killed by unknown assailants. Several pro-Iran groups and figures have accused the United States and other outside actors of instigating the unrest, in line with Iran-linked figures' broader accusations about alleged U.S. meddling in government formation talks.3 U.S. officials have attributed several rocket attacks near U.S. facilities in Iraq to Iran, stating that the United States would respond directly to attacks on U.S. facilities or personnel by Iranian-backed entities. 4 On September 28, the Trump Administration announced it would temporarily remove U.S. personnel from the U.S. Consulate in Basra in response to threats from Iran and Iranian-backed groups.5 The government-formation process in Iraq is ongoing, and leaders have taken formal steps to fill key positions since election results were finalized on August 19. In successive governments, Iraq's Prime Minister has been a Shia Arab, the President has been a Kurd, and the Council of Representatives Speaker has been a Sunni Arab, reflecting an informal agreement among leaders of these communities. On September 3, the first session of the newly elected COR was held, and, on September 15, members elected Mohammed al Halbousi, the governor of Anbar, as Speaker. Hassan al Kaabi of the Sa'iroun list and Bashir Hajji Haddad of the KDP were elected as First and Second Deputy Speaker, respectively. On October 2, the COR met to elect Iraq's President, with rival Kurdish parties nominating competing candidates.6 COR members chose the PUK candidate - former KRG Prime Minister and former Iraqi Deputy Prime Minister Barham Salih - in the second round of voting. President Salih immediately named former Minister of Oil Adel Abd al Mahdi as the Prime Minister-designate of the largest bloc of COR members and directed him to form a government for COR consideration. Within thirty days (by November 1), the Prime Minister-designate is to present a slate of cabinet members and a government platform for COR approval.

The contest to form the largest bloc and designate a prime minister candidate was shaped by the protests and attacks described above, with candidates drawn from the ranks of former officialdom disadvantaged by the public's apparent anti-incumbent mood. On September 7, the representative of Iraqi Shia supreme religious authority Grand Ayatollah Ali al Sistani decried Iraq's transformation into "an arena for regional and international conflicts" and said, "there should be pressure toward forming a new government that is different from the previous ones and to ensure that it takes into consideration the standards of efficiency, integrity, courage, firmness, and loyalty to the country and people as a basis for the selection of senior officials."7 A subsequent statement issued by Sistani's office denied rumors that Sistani had intervened to select or reject specific prime ministerial candidates and emphasized the prerogatives and duties of Iraq's elected leaders to do so.8 Notably, this second statement further attributed to Sistani the view that current and former Iraqi officials should not lead Iraq's next government. In the wake of these messages from Grand Ayatollah Al Sistani's office, Prime Minister Abadi announced that he would not "cling to power," which many observers regarded as the end of his public campaign for a second term.9 Badr Organization and Fatah coalition leader Hadi al Ameri also announced that would not pursue the position of prime minister. Many observers of Iraqi politics regard Adel Abd al Mahdi as a compromise candidate acceptable to coalitions that have formed around the Fatah list on the one hand and the Sa'irun list on the other. While some in Congress have expressed concern about reported Iranian involvement in negotiations that led to Abd al Mahdi's nomination, Administration responses have highlighted past U.S. work with him and suggest they view the nomination as acceptable.10 Abd al Mahdi has been a key interlocutor for U.S. officials since shortly after the 2003 U.S.-led invasion that overthrew Saddam Hussein's regime. At the same time, he has been a prominent figure in the Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq (ISCI), which has historically received substantial backing from Iran. He served as Minister of Finance in Iraq's appointed interim government and led the country's debt relief initiatives. He has publicly supported an inclusive approach to sensitive political, religious, and inter-communal issues, but his relationships with other powerful Iraqi Shia forces and Iran raise some questions about his ability to lead independently.11 Looking ahead, the new government's viability and the Prime Minister's freedom of action on controversial issues will be shaped by the durability of agreements among Iraqi coalitions and progress on citizens' priorities. Since its founding in 2014, Iraq's Popular Mobilization Committee (PMC) and its associated militias—the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF)—have contributed to Iraq's fight against the Islamic State. Despite appreciating those contributions, some Iraqis and outsiders have raised concerns about the future of the PMC/PMF and some of its members' ties to Iran.12 At issue has been the apparent unwillingness of some PMC/PMF entities to subordinate themselves to the command of Iraq's elected government and the ongoing participation in PMC/PMF operations of groups reported to receive direct Iranian support. In February 2018, the U.S. intelligence community told Congress that Iranian support to the PMC and "Shia militants remains the primary threat to U.S. personnel in Iraq." The community assessed that "this threat will increase as the threat from ISIS recedes, especially given calls from some Iranian-backed groups for the United States to withdraw and growing tension between Iran and the United States."13 Many PMF-associated groups and figures participated in the May 2018 national elections under the auspices of the Fatah coalition headed by Ameri.14 Ameri and other prominent PMF-linked figures such as Asa'ib Ahl al Haq (League of the Righteous) leader Qa'is al Khazali nominally disassociated themselves from the PMF in late 2017, in line with legal prohibitions on the participation of PMF officials in politics.15 Nevertheless, their movements' supporters and associated units remain integral to some ongoing PMF operations, and the Fatah coalition's campaign was arguably boosted by its members' past PMF activities. During the election and in its aftermath, the key unresolved issue with regard to the PMC/PMF has remained the incomplete implementation of a 2016 law calling for the PMF to be incorporated as a permanent part of Iraq's national security establishment. In addition to outlining salary and benefit arrangements important to individual PMF volunteers, the law calls for all PMF units to be placed fully under the authority of the commander-in-chief [Prime Minister] and to be subject to military discipline and organization. Through mid-2018, some PMF units were being administered in accordance with the law, but others have remained outside the law's directive structure. This includes some units associated with Shia groups identified by U.S. government reports as receiving or as having received Iranian support.16 According to August 2018 oversight reporting on Operation Inherent Resolve, Defense Department sources report that electioneering and government formation talks had "prevented any meaningful efforts to integrate the PMF into the ISF or the Ministries of Defense or Interior" through mid-year. In general, the popularity of the PMF and broadly expressed popular respect for the sacrifices made by individual volunteers in the fight against the Islamic State create complicated political questions. From an institutional perspective, one might assume Iraqi political leaders would share incentives to assert full state control over all PMF units and other armed groups and to ensure the full implementation of the 2016 PMF law. However, in practice, different figures appear to favor different approaches, with some Iran-aligned figures appearing to prefer a model that preserves the relative independence of units loyal and responsive to them. Iraqi leaders arguably benefit politically from continuing to embrace the PMF and its personnel and from supporting volunteers during their demobilization or transition into security sector roles. Nevertheless, there also may be political costs to appearing too supportive of the PMF relative to other national security forces or to embracing Iran-linked units in particular. Proposals for fully dismantling the PMC/PMF structure appear to be politically untenable at present, and, given the ongoing role PMF units are playing in security operations against remnants of the Islamic State in some areas, might create opportunities for IS fighters to exploit. Forceful confrontation between Iraqi security forces and Iran-backed groups within the PMF structure or outside of it could precipitate civil conflict and a crisis in Iraq-Iran relations. Attempts by Iraqi Security Forces to investigate allegations of illicit activity by some PMF units and Shia armed groups have resulted in violence in 2018. The Fatah coalition reacted angrily to Abadi's August 2018 decision to dismiss Fatah-aligned National Security Advisor and PMC head Falih al Fayyadh, calling the decision "illegal."17 Grand Ayatollah Al Sistani's office and his personal representatives have spoken directly about the importance of establishing and maintaining institutional control of all security forces in Iraq. This suggests that Sistani could make further public statements on the issue in the event that a figure with a different view takes office as prime minister or if some armed factions resist future government efforts at security force integration.

Areas of Influence as of September 17, 2018 Sources: Congressional Research Service using ArcGIS, IHS Markit Conflict Monitor, U.S. government, and United Nations data. The Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) held an official advisory referendum on independence from Iraq on September 25, 2017, despiterequests from the national government of Iraq, the United States, and other external actors to delay or cancel it. Kurdish leaders held the referendum on time and as planned, with more than 72% of eligible voters participating and roughly 92% voting "Yes." The referendum was held across the KRI and in other areas that were then under the control of Kurdish forces, including some areas subject to territorial disputes between the KRG and the national government, such as the multiethnic city of Kirkuk, adjacent oil-rich areas, and parts of Ninewa governorate populated by religious and ethnic minorities. Kurdish forces had secured many of these areas following the retreat of national government forces in the face of the Islamic State's rapid advance across northern Iraq in 2014. Elections for the Kurdistan National Assembly were delayed in November 2017 and held on September 30, 2018. Preliminary results suggest that the KDP won a plurality of the 111 seats, with the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) and smaller opposition and Islamist parties winning the balance. U.S. officials have encouraged Kurds and other Iraqis to engage on issues of dispute and to avoid unilateral military actions that could further destabilize the situation. Iraqi national government and KRG officials continue to engage U.S. counterparts on related issues. The public finances of the national government and the KRG remain strained, amplifying the pressure on leaders working to address the country's security and service-provision challenges. On a national basis, the combined effects of lower global oil prices from 2014 through mid-2017, expansive public-sector liabilities, and the costs of the military campaign against the Islamic State have exacerbated budget deficits.20 The IMF estimated Iraq's 2017-2018 financing needs at 19% of GDP. Oil exports provide nearly 90% of public-sector revenue in Iraq, while non-oil sector growth has been hindered over time by insecurity, weak service delivery, and corruption. Iraq's oil production and exports have increased since 2016, but fluctuations in oil prices undermined revenue gains until the latter half of 2017. Revenues have since improved, but Iraq has agreed to manage its overall oil production in line with mutually agreed Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) output limits. In August 2018, Iraq exported an average of 4 million barrels per day (mbd, including KRG-administered oil exports), above the March 2018 budget's 3.8 mbd export assumption and at prices well above the budget's $46 per barrel benchmark.21 The IMF projects modest GDP growth over the next five years and expects growth to be stronger in the non-oil sector if Iraq's implementation of agreed measures continues as oil output and exports plateau. Fiscal pressures are more acute in the Kurdistan region, where the fallout from the national government's response to the September 2017 referendum has further sapped the ability of the KRG to pay salaries to its public-sector employees and security forces. The KRG's loss of control over significant oil resources in Kirkuk governorate coupled with changes implemented by national government authorities over shipments of oil from those fields via the KRG-controlled export pipeline to Turkey have contributed to a sharp decline in revenue for the KRG. FebruarySeptember 2018, Iraq Ministry of Finance, and International Organization for Migration.

Developments in 2017 and 2018

Iraq Declares Victory against the Islamic State, Pursues Fighters

The Kurdistan Region's September 2017 Referendum on Independence

2018, Iraq Ministry of Finance, and International Organization for Migration.

Uncertainty and Confrontation in Iraq's Disputed Territories

The Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) held an official advisory referendum on independence from Iraq on September 25, 2017, in spite of requests from the national government of Iraq, the United States, and other external actors to delay or cancel it. Kurdish leaders held the referendum on time and as planned, with more than 72% of eligible voters participating and roughly 92% voting "Yes." The referendum was held across the KRI and in other areas that were then under the control of Kurdish forces, including some areas subject to territorial disputes between the KRG and the national government, such as the multiethnic city of Kirkuk, adjacent oil-rich areas, and parts of Ninewa governorate populated by religious and ethnic minorities. Kurdish forces had secured many of these areas following the retreat of national government forces in the face of the Islamic State's rapid advance across northern Iraq in 2014.

In the wake of the referendum, Iraqi national government leaders imposed a ban on international flights to and from the Kurdistan region, and, in October 2017, Prime Minister Abadi ordered Iraqi forces to return to the disputed territories that had been under the control of national forces prior to the Islamic State's 2014 advance, including Kirkuk. A handful of clashes between national and Kurdish security forces resulted in some casualties on both sides, but Kurdish parties—who had been divided among themselves over the wisdom of the referendum and relations with Baghdad—mostly directed their forces to withdraw to pre-2014 lines without incident. More than 340,000 civilians were internally displaced from the disputed territories in the postreferendum confrontations, with more than 200,000 since having returned. The involvement of some Iran-backed Popular Mobilization Force (PMF) militia units in Iraqi national forces' operations in the disputed territories has fueled concerns about Iranian influence in Iraq, as have reports about attempts by Iranian officials to pressure Kurdish leaders over related issues.

The postreferendum changes in territorial control in the disputed territories have upended the Kurds' financial and political prospects, and related disputes have fueled further division among Kurdish leaders and parties. Former KRG President Masoud Barzani—who, along with his Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) faction, was considered the driving force behind the referendum—announced that he will not seek reelection and directed that executive authority be exercised by his nephew, KRG Prime Minister Nechirvan Barzani, and other KRG entities until elections are held. The Kurdistan National Assembly then voted to delay KRG elections that had been planned for November 2017. As of March 2018, no KRG election date had been set.

Prime Minister Abadi has reiterated the national government's view that the September 2017 referendum was "unconstitutional," and he and Iraq's national legislature and courts have called for its results to be "cancelled."2 The Prime Minister's statements continue to emphasize the national government's demands for full control over national borders, customs procedures, airports, and energy exports pursuant to the national government's reading of the 2005 constitution. The ban on international flights to and from the KRI has been extended to May 2018, but negotiating committees have reached proposed agreements on some "unresolved problems."3 In January 2018 Iraqi national authorities travelled to the KRI, audited the payroll of select KRG ministries, and deposited funds in accounts to be used to pay the salaries of some KRG employees.4

Senior leaders on both sides are publicly expressing satisfaction with the content and pace of ongoing talks and confidence that some disputes can be resolved. That said, tangible examples of durably settled issues between the KRG and Baghdad are hard to find, and discussions are more active in some areas than in others. As noted above, security forces from both sides remain deployed across from each other at various fronts throughout the disputed territories, including deployments near the strategically sensitive triborder area of Iraq, Syria, and Turkey (Figure 2). The United Nations Assistance Mission in Iraq (UNAMI) reported to the Security Council in mid-January that "No technical negotiations have been held between military officials from the federal and Kurdistan Regional Governments since the end of October 2017, and an uneasy, informal truce has taken effect in place of a formal agreement."

U.S. officials continue to encourage Kurds and other Iraqis to engage on issues of dispute and to avoid unilateral military actions that could further destabilize the situation. Iraqi national government and KRG sources report that formal U.S.-brokered security negotiations are not under way, but U.S. military and civilian officials remain engaged with all parties in support of deconfliction. Deputy Secretary of State John Sullivan travelled to Iraq in late January 2018 and met with national government and KRG leaders, reiterating U.S. support for dialogue.

May 2018 Elections

The national legislative elections planned for May 12, 2018, are the dominant political story in Iraq, and daily news reports describe an evolving competitive landscape among leaders, parties, and coalitions seeking to win seats in the next Council of Representatives (COR). Some Iraqis have lobbied for the election to be delayed, citing concerns about security, damaged infrastructure, and the continuing internal displacement of more than 2.5 million of their fellow citizens. In January 2018, Iraq's courts ruled that the elections cannot be delayed, and election authorities are making preparations to enable all Iraqis, regardless of location and local conditions, to have the opportunity to participate.

As of March 2018, two bills amending the 2013 national legislative elections law have been endorsed by the Council of Representatives, and some proposed changes may face judicial review. The adopted amendments prohibit active members of the security forces from standing as candidates and require the use of electronic voting systems. Governorate council elections were due to be held in 2017 but were delayed and are now set to be held in December 2018, six months after the national legislative elections.

Following the May 2018 election, results are to be tabulated and coalition leaders are expected to negotiate to select a prime ministerial candidate to form a government for approval by the newly seated COR. The pace of postelection negotiations may be affected by national observance of Ramadan, which is expected to begin on May 15 and last until June 14, 2018.

Prime Minister Abadi has announced his plan to lead a coalition of mostly Shia parties and independent Sunni figures under the framework of his Victory (Nasr) Alliance. In launching his own coalition, Abadi is competing with Vice President and former Prime Minister Nouri al Maliki, who, like Abadi, is a leading member of the Dawa Party. Maliki's State of Law alliance has been critical of Abadi's leadership, and some State of Law members are vocal opponents of Iraq's security partnership with the United States. Several former leaders of the Popular Mobilization Force (PMF) militias organized to help fight the Islamic State are participating in the elections as candidates under the rubric of the Fatah Alliance (see textbox below).

Other prominent Iraqi figures have organized coalitions and lists to contest the election, including a largely Sunni list led by Vice President Osama al Nujayfi and the National Alliance jointly led by Vice President Iyad Allawi, COR Speaker Salim al Juburi, and former Deputy Prime Minister Salih al Mutlaq. Among Shia leaders, Ammar al Hakim's Wisdom (Hikma) movement has formally withdrawn from the Prime Minister's coalition, but Hakim reportedly intends to coordinate with Abadi during government formation negotiations after the election. Shia cleric Muqtada al Sadr is directing his followers to support the multiparty, anticorruption oriented Sa'irun coalition. Sadr has criticized the participation of PMF leaders in the election and is campaigning on a populist reform and anticorruption platform.

Kurdish parties are not running a coordinated campaign or joint list but may prove influential during government formation negotiations. The Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) are running separately, and the KDP may not campaign in some disputed areas controlled by federal government forces. The Gorran (Change) movement plans to run as part of the Nishtiman (Homeland) alliance along with the Coalition for Democracy and Justice of former KRG Prime Minister Barham Saleh and the Kurdistan Islamic Group (Komal).

|

Iraq's Popular Mobilization Forces and the 2018 Election Since its founding in 2014, Iraq's Popular Mobilization Commission (PMC) and its associated militias—the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF)—have contributed to Iraq's fight against the Islamic State, even as some of its leaders and units have raised concerns among Iraqis and outsiders about the PMF's future and some of its members' ties to Iran. Key political issues at present concern implementing a 2016 law calling for the PMF's incorporation as a permanent part of Iraq's national security establishment and managing the participation of PMF-associated figures in the 2018 election in line with provisions of that law that call for politically active individuals to sever their PMF ties. Prime Minister Abadi initially proposed pairing his Victory Alliance with the Fatah coalition headed by Badr Organization leader Hadi al Ameri, but Fatah leaders withdrew from the arrangement shortly after its announcement. Ameri and other prominent figures who helped lead the Popular Mobilization Forces during the 2014-2017 fight with the Islamic State such as Asa'ib Ahl al Haq (League of the Righteous) leader Qa'is Khazali, have nominally disassociated themselves from the PMF, in line with legal prohibitions on the participation of PMF officials in politics.5 Nevertheless, their movements' supporters and associated units remain integral to some ongoing PMF operations and their public images remain closely, if now informally, linked to their past PMF leadership activities. Some observers continue to express surprise and concern about Abadi's apparent willingness to coordinate politically with figures that remain associated with the PMF movement and particularly with figures reported to have close ties with PMF groups that have received support from Iran. In December, Prime Minister Abadi had reiterated his insistence that PMF leaders delink themselves from the force if they intended to compete politically. He also restated his intention to proceed with the integration of the PMF into national security bodies according to the 2016 PMF law. Abadi's statements to this effect followed closely on the heels of an address given in mid-December by Abdul Mahdi al Karbala'i, a senior representative of Grand Ayatollah Sistani, whose 2014 fatwa mobilized the PMF and legitimizes its ongoing operations in the eyes of some volunteers and citizens. Karbala'i credited the PMF volunteers with saving Iraq from the Islamic State and called on Iraqis to continue to "make use" of their "important energies within constitutional and legal frameworks on the issue of restricting weapons to the state and drawing the right track for the role of these heroes in protecting the country... ."6 He further called on PMF volunteers to defend the privileged status and respect they had earned by refusing to use their positions and experiences for political purposes or gain.7 Karbala'i was targeted in an assassination attempt in January 2018. The popularity of the PMF and broadly expressed respect for the sacrifices made by individual volunteers in the fight against the Islamic State create complicated political questions for the Prime Minister and other Iraqi leaders. On the one hand, there may be a political benefit in continuing to embrace the PMF and its personnel and in supporting volunteers during their demobilization or transition into security sector roles. On the other hand, there may be political costs to appearing too supportive of the PMF generally or to embracing Iran-linked units in particular. The effect of Abadi's proposal to cooperate with the Fatah Alliance on his political prospects remains to be seen. To date, limited progress has been made in the implementation of the 2016 PMF law that Iraqis adopted to provide for a permanent role for the PMF as an element of Iraq's national security sector. The law calls for the PMF to be placed under the command authority of the commander-in-chief and to be subject to military discipline and organization. Some PMF units have since been integrated, but many remain outside the law's directive structure, including some units associated with groups identified by the State Department's 2016 Country Reports on Terrorism as receiving Iranian support.8 The presence of Iran-aligned PMF forces in disputed territories remains a source of concern to KRG officials and some members of local communities. In February 2018, the U.S. intelligence community told Congress that "Iran's support for the Popular Mobilization Committee (PMC) and Shia militants remains the primary threat to U.S. personnel in Iraq. We assess that this threat will increase as the threat from ISIS recedes, especially given calls from some Iranian-backed groups for the United States to withdraw and growing tension between Iran and the United States."9 |

Economic and Fiscal Challenges Continue

Ongoing fiscal crises strain the public finances of the national government and the KRG, amplifying the pressure on leaders working to address the country's security and political challenges. On a national basis, the combined effects of lower global oil prices from 2014 through mid-2017, expansive public sector liabilities, and the costs of the military campaign against the Islamic State have created budget deficits—estimated at 12% of GDP in 2015 and 14% of GDP in 2016.10 The IMF estimates Iraq's 2017-2018 financing needs at 19% of GDP. Oil exports continue to provide nearly 90% of public sector revenue in Iraq, while non-oil sector growth has been hindered over time by insecurity, weak service delivery, and corruption.

Iraq's oil production and exports have increased since 2016, but fluctuations in oil prices undermined revenue gains until the latter half of 2017 and early 2018, with revenues now improving. Iraq has agreed to manage its overall oil production in line with mutually agreed Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) output limits, and current production levels remain within agreed OPEC commitments. In January 2018, Iraq exported an average of 3.5 million barrels per day (mbd, excluding KRG-administered oil exports), below the amended July 2017 budget's 3.75 mbd export assumption but at prices well above the budget's $45 per barrel benchmark.11 The IMF projects modest GDP growth over the next five years and expects growth to be stronger in the non-oil sector if Iraq's implementation of agreed measures continues as oil output and exports plateau.

Fiscal pressures are more acute in the Kurdistan region, where the fallout from the national government's response to the September 2017 referendum has further sapped the ability of the KRG to pay salaries to its public sector employees and security forces. The KRG's loss of control over significant oil resources in Kirkuk governorate coupled with changes implemented by national government authorities over shipments of oil from those fields via the KRG-controlled export pipeline to Turkey have contributed to a sharp decline in revenue for the KRG. Kurdish officials also report that the ban on international flights to and from the KRI is negatively affecting the region's economy, although ongoing discussions between KRG and national government officials could conceivably support the amendment or lifting of flight limits in the near future. As noted above, Iraqi authorities have initiated audits of payroll and other records for some KRG ministries and made funds available to temporarily support the salaries of public employees in the KRI health and education sectors.

Related issues shaped consideration of the 2018 budget in the COR, with Kurdish representatives criticizing the government's budget proposal to allocate the KRG a smaller percentage of funds in 2018 than the 17% benchmark reflected in previous budgets. National government officials argue that KRG resources should be based on a revised population estimate, and the 2018 budget adopted in March 2018 does not specify a fixed percentage or amount for the KRG and requires the KRG to place all oil exports under federal control in exchange for financial allocations for verified expenses.

Humanitarian Issues and Stabilization

Humanitarian Conditions

U.N. officials report several issues of ongoing humanitarian concern including harassment by armed actors and threats of forced return.22 Humanitarian conditions remain difficult in many conflict-affected areas of Iraq, but December 2017 marked the first month since December 2013 that there were more Iraqis who returned to their home areas thanoutnumbered those who remained as internally displaced persons (IDPs) or became newly displaced. As of February 28September 15, more than 3.54 million Iraqis had returned to their districts since 2014, while more than 2.31.9 million individuals remained displaced.23 These figures include those who were displaced and returned home in disputed areas in the wake of the September 2017 KRG referendum on independence.1224 Ninewa governorate is home to the largest number of IDPs, due to the reflecting the lingering effects of the intense military operations against the Islamic State in Mosul and northwestern areas of the governorate other areas during 2017 (Table 2). Estimates suggest thousands of civilians were killed or wounded during the Mosul battle, which displaced more than 1 million people.

The Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI) hosts approximately 31nearly 38% of the remaining IDP population in Iraq, and .

IDP numbers in the KRI have declined since early 2017, though not as rapidly as in some other governorates. Conditions for IDPs in Dohuk governorate remain the most challenging in the KRI, with roughly halfmore than 57% of Dohuk-based IDPs living in camps or critical shelters as of December 2017September 2018 according to International Organization for Migration surveys.

The U.N.'s 2018 Iraq humanitarian appeal expected that as many as 8.7 million Iraqis would require some form of humanitarian assistance in 2018 and sought $569 million to reach 3.4 million of them.25 As of October 2018, the appeal was 60% met with $342 million in funds provided and more than $250 million in additional funds provided outside the plan.26U.N. officials report that access restrictions continue to hinder humanitarian operations in some areas.13 The 2017 Humanitarian Response Plan for Iraq identified more than $984 million in needs and was 91% met, with nearly $400 million in additional funds provided outside the plan.14 The 2018 Iraq appeal expects that as many as 8.7 million Iraqis will require some form of humanitarian assistance in 2018 and seeks $569 million to reach 3.4 million of them.15

Table 2. IOM Estimates of IDPs by Location in Iraq

As of January 15, 2018

|

IOM Estimates of IDPs |

% Change |

|||

|

Governorate |

January 2017 |

January 2018 |

|

|

September 2018 |

|

Suleimaniyah |

153,816 |

188,142 |

|

|

|

Erbil |

346,080 |

253,116 |

|

|

|

Dohuk |

397,014 |

362,670 |

|

|

|

KRI Total |

896,910 |

806,976 |

|

|

|

Ninewa |

409,020 |

795,360 |

|

|

|

Salah al Din |

315,876 |

241,404 |

|

|

|

Baghdad |

393,066 |

176,700 |

|

|

|

Kirkuk |

367,188 |

172,854 |

|

|

|

Anbar |

268,428 |

108,894 |

|

|

|

Diyala |

75,624 |

81,972 |

|

|

Source: International Organization for Migration, Iraq Displacement Tracking Monitor Data.

Stabilization and Reconstruction

At a February 2018 reconstruction conference in Kuwait, Iraqi authorities described more than $88 billion in short- and medium-term reconstruction needs, spanning various sectors and different areas of the country.1627 Countries participating in the conference offered approximately $30 billion worth of loans, investment pledges, export credit arrangements, and grants in response. The Trump Administration actively supported the participation of U.S. companies in the conference and announced its intent to pursue $3 billion in Export-Import Bank support for Iraq.

U.S. stabilization assistance to areas of Iraq that have been liberated from the Islamic State is directed through the United Nations Development Program (UNDP)-administered Funding Facility for Stabilization (FFS), which includes a Funding Facility for Immediate Stabilization (FFIS), a Funding Facility for Expanded Stabilization (FFES), and Economic Reform Facilities for the national government and the KRI. U.S. contributions to FFIS support stabilization activities under each of its "Four Windows": (1) light infrastructure rehabilitation, (2) livelihoods support, (3) local official capacity building, and (4) community reconciliation programs.17 As of January 2018, UNDP Iraq reported that the FFS had received more than $420 million in resources since its inception in mid-2015, and more than 1,600 stabilization projects were underway with the support of UNDP-managed funding.

Iraq hopes.28 According to UNDP data, the FFS has received more than $690 million in resources since its inception in mid-2015, with 1,100 projects reported completed and a further 1,250 projects underway or planned with the support of UNDP-managed funding.29 In August 2018, UNDP identified a "funding gap" of $505 million for stabilization projects in what it describes as "strategic red box zones" (i.e., "the areas that are most vulnerable to the re-emergence of violent extremism and were last to be liberated") in Ninewa, Anbar, and Salah al Din governorates.30 UNDP highlights unexploded ordnance, customs clearance delays, and the growth in volume and scope of FFS projects as challenges to its ongoing work.31

Iraqi leaders hope to attract considerable private sector investment to help finance its reconstruction needs and underwrite a new economic chapter for the country. The size of Iraq's internal market and its advantages as a low-cost energy producer with identified infrastructure investment needs help make it attractive to investors, but overcoming persistent concerns about security, service reliability, and corruption may prove challenging. The outcome of the 2018 election and the new Iraqi leadership's statements on reform effortsformation of the new Iraqi government and its reform plans may provide key signals to parties exploring investment opportunities.

Potential Issues forin the 115th Congress

As Congress considershas considered the Trump Administration's requests for FY2019 foreign assistance and defense funding, Iraqis arehave been engaged in a competitive election campaign andelectioneering and government formation negotiations, while working to rebuild war-torn areas of their country. AThe final FY2018 appropriations agreement may makeacts approved in March 2018 (P.L. 115-141) made additional U.S. funding available for U.S. defense programs and contributions to immediate post-IS stabilization efforts, and may renewwhile also renewing authorities for U.S. economic loan guarantees and military assistance that have helped Iraq overcome its financial difficulties. The Trump Administration's decisions about the direction and content of planned U.S. assistance efforts in 2018 and beyond may be shaped by the contours and outcome of the Iraqi election. If Prime Minister Abadi emerges as the head of Iraq's next government, continuity may prevail in patterns of U.S. assistance. At the same time, the empowerment of more anti-U.S. actors also could prompt changes in the bilateral relationship.

Defense authorization (P.L. 115-232) and appropriation (Division A of P.L. 115-245) legislation enacted for FY2019 extends congressional authorization for U.S. training, equipping, and advisory programs for Iraqi security forces until December 2020 and makes $850 million in additional defense funding available for security assistance programs through FY2020. Congress has limited the availability of these funds, authorizing the obligation or expenditure of no more than $450 million for Iraq train and equip efforts until the Administration submits required strategy and oversight reporting.32

The FY2018 NDAA [Section 1224(c) of P.L. 115-91] modified the authority of the Office of Security Cooperation at the U.S. Embassy in Iraq (OSC-I) to widen the range of forces that the office may engage with professionalization and management assistance from Ministry of Defense and Counter Terrorism Service personnel to include all "military and other security forces with a national security mission."33 The Administration's FY2019 defense funding request outlines plans for U.S. training of Iraqi border security forces, energy security forces, emergency response police units, Counterterrorism Service forces, and ranger units.

The FY2019 Continuing Appropriations Act (Division C of P.L. 115-245) makes funds available for foreign operations programs in Iraq on the terms and at the levels provided for in FY2018 appropriations through December 7, 2018. Foreign operations appropriations bills considered by the House and Senate would appropriate FY2019 funds for Iraq programs differently.

- The House version of the FY2019 Foreign Operations Appropriations bill (H.R. 6385) would make funds available "to promote governance and security, and for stabilization programs, including in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq …in accordance with the Constitution of Iraq." The accompanying report (H.Rept. 115-829) would direct $50 million in funds made available by the act for stabilization and recovery be used "for assistance to support the safe return of displaced religious and ethnic minorities to their communities in Iraq."

- The Senate version (S. 3108) and accompanying report (S.Rept. 115-282) would make $429.4 million available in FY2019 funding across various accounts, including $250 million in Foreign Military Financing assistance not requested by the Trump Administration. The Senate version also would direct that additional assistance monies in various accounts be made available for a $250 million Relief and Recovery Fund (RRF) for areas liberated or at risk from the Islamic State and other terrorist organizations, and the accompanying report contains a further direction that $100 million in funds appropriated for RRF purposes in prior acts be made available for programs in Iraq.

The Trump Administration signaled that decisions about future U.S. assistance efforts will be shaped by the outcome of Iraqi government formation talks. In September 2018, U.S. officials suggested they would like to see prevailing patterns of U.S. assistance continue, but an unnamed senior U.S. official also said that the Administration is prepared to reconsider U.S. support to Iraq if individuals perceived to be close to or controlled by Iran assume positions of authority in Iraq's new government.34 Legislation enacted and under consideration in the second session of the 115th Congress would require annual reporting on Iraqi entities and individuals receiving Iranian support and would codify authorities currently available to the President under executive order to place sanctions on individuals threatening the security or stability of Iraq (see "The United States and Iran in Iraq" below).

U.S. Military Operations

Iraqi military and counterterrorism operations against scattered supporters of the Islamic State group are ongoing, and the United States military and its coalition partners continue to provide support to those efforts at the request of the Iraqi government. The Trump and Obama Administrations have bothU.S. military operations against the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria are organized under the command of Combined Joint Task Force – Operation Inherent Resolve (CJTF-OIR).

The Trump Administration, like the Obama Administration, has cited the 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF, P.L. 107-40) as the domestic legal authorization for U.S. military operations against the Islamic State in Iraq and referrefers to both collective and individual self-defense provisions of the U.N. Charter as the relevant international legal justifications for ongoing U.S. operations in Iraq and Syria. The U.S. military presence in Iraq is governed by an exchange of diplomatic notes that reference the security provisions of the 2008 bilateral Strategic Framework Agreement.1835 This arrangement has not required approval of a separate security agreement by Iraq's Council of Representatives.

The overall volume and pace of kinetic U.S. operationsU.S. strikes against IS targets appears to have subsided since latein Iraq has diminished since the end of 2017, with U.S. training efforts for various Iraqi security forces ongoing at various locations, including in the Kurdistan region, pursuant to the authorities granted by Congress for the Iraq Train and Equip Program and for the activities of the Office of Security Cooperation-Iraq (OSC-I) at the U.S. Embassy in Baghdad.19

The cost of military operations under Operation Inherent Resolve against the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria as of June 30, 2017, was $14.3 billion, and, through FY2017, Congress had appropriated more than $3.6OSC-I.36 As of August 2018, U.S. and coalition training had benefitted more than 150,000 Iraqi security personnel since 2014. From FY2015 through FY2019, Congress authorized and appropriated more than $5.8 billion for train and equip assistance in Iraq (Table 3). As of September 2017, the Department of Defense (DOD) reported that there were then nearly 8,900 U.S. uniformed military personnel in Iraq, although precise numbers have been fluid based on operational needs and deployment schedules.20 In February 2018, General Joseph Votel, Commander of U.S. Central Command, confirmed that there has been a further reduction in the number of U.S. military personnel and changes in U.S. capabilities in Iraq.21 Earlier in February, the U.S. military confirmed that the "continued coalition presence in Iraq will be conditions-based, proportional to the need, and in coordination with the government of Iraq."22 From August 2014 through January 30, 2018, 52 U.S. military personnel and DOD civilians have been killed or have died as part of Operation Inherent Resolve, and an additional 58 U.S. persons have been wounded.

Security Assistance to the Kurdistan Regional Government in thousands of dollars

|

FY2015

|

FY2016

|

FY2017 Requests

|

FY2018 Iraq-Specific Request

|

FY2019 Iraq-Specific Request

|

Iraq Train and Equip Fund

|

1,618,000

|

715,000

|

630,000

|

-

|

-

|

Additional Counter-ISIL Train and Equip Fund

289,500 (FY17 CR)

|

-

|

-

|

446,400

|

1,269,000

|

850,000

|

Total

|

1,618,000

|

715,000

|

1,365,900

|

1,269,000

|

850,000 Source: Executive branch appropriations requests and appropriations legislation. The Trump Administration has not reported the number of U.S. personnel in Iraq since September 2017.37 In February 2018, General Joseph Votel, Commander of U.S. Central Command, stated that there has been a reduction in the number of U.S. military personnel and changes in U.S. capabilities in Iraq from 2017 levels.38 U.S. military sources have stated that the "continued coalition presence in Iraq will be conditions-based, proportional to the need, and in coordination with the government of Iraq."39 As of October 2018, 67 U.S. military personnel and DOD civilians have been killed or have died as part of OIR, and 72 U.S. persons have been wounded. Through March 2018, OIR operations since August 2014 had cost $23.5 billion.40 Assistance to the Kurdistan Regional Government and in the Kurdistan Region Congress has authorized the President to provide U.S. assistance to the Kurdish peshmerga and certain Sunni and other local security forces with a national security mission in coordination with the Iraqi government, and to do so directly under certain circumstances. Pursuant to a 2016 U.S.-KRG memorandum of understanding (MOU), the United States has offered more than $400 million in defense funding and in-kind support to the Kurdistan Regional Government of Iraq, delivered in smaller monthly installments. The December 2016 continuing resolution (P.L. 114-254) included $289.5 million in Kurdish officials report that U.S. training support and consultation on plans to reform the KRG Ministry of Peshmerga and its forces continue. The Department of Defense reports that it has resumed paying the salaries of peshmerga personnel in units aligned by the Ministry of Peshmerga, after a pause following the September 2017 independence referendum. |

U.S. Foreign Assistance

In July 2017, the Trump Administration notified Congress of its intent to obligate up to $250 million in FY2017 Foreign Military Financing (FMF) funding for Iraq in part to support the costs of continued loan-funded purchases of U.S. defense equipment and to fund Iraqi defense institution building efforts. Congressionally authorized U.S. loan guarantees also supported a successful Iraqi bond issue in early 2017. The Administration has requested $1.269 billion in FY2018 defense funding to train and equip Iraqis along with $347.86 million for FY2018 foreign assistance, including $300 million for post-IS stabilization. The corresponding FY2019 requests are for $850 million in defense funding and $199.86 million in foreign assistance (Table 4). Since 2014, the United States has contributed more than $1.7 billion to humanitarian relief efforts in Iraq,23 including more than $607 million in humanitarian support in FY2017 and FY2018.24

Since mid-2016, the executive branch has notified Congress of its intent to obligate $265.3 million in assistance funding to support UNDP FFS programs, including post-IS stabilization funding made available through FY2018 in the December 2016 continuing resolution (P.L. 114-254, see textbox below).25 The Trump Administration requested an additional $300 million in FY2018 Economic Support and Development Fund (ESDF) monies for Iraq, a portion of which would fund continued U.S. contributions to post-IS stabilization programs. House and Senate versions of the FY2018 foreign operations appropriations bill would make Economic Support Fund (ESF) monies available for contributions to stabilization in Iraq on different terms. The FY2019 request seeks $150 million in ESDF for stabilization and other programs.

U.S. contributions to efforts to stabilize the Mosul Dam on the Tigris River are ongoing, and the Trump Administration notified Congress of its intent to obligate an additional in $65 million in State Department and Defense Department funds in December 2017 and January 2018. In July 2017, the State Department noted that while Iraq had begun work to stabilize the dam, "it is impossible to accurately predict the likelihood of the dam's failing…."26

In recent years, the U.S. government has provided State Department- and USAID-administered assistance to Iraq to support a range of security and economic objectives. U.S. Foreign Military Financing (FMF) funds have supported the costs of continued loan-funded purchases of U.S. defense equipment and helped fund Iraqi defense institution building efforts. Congressionally authorized U.S. loan guarantees also have supported successful Iraqi bond issues to help Baghdad cover its fiscal deficits. Since 2014, the United States has contributed more than $1.7 billion to humanitarian relief efforts in Iraq,41 including more than $607 million in humanitarian support in FY2017 and FY2018.42

The Administration's FY2019 request seeks more than $199 million for stabilization and other non-military assistance programs in Iraq (Table 4). The Senate version of the FY2019 foreign operations appropriations act (S. 3108, S.Rept. 115-282) would appropriate $150 million in ESF, along with $250 million in Foreign Military Financing and other security assistance funds. The Senate version also would direct that $50 million in FY2019 ESF funds be provided for stabilization in Iraq, in addition to $100 million in previously appropriated Relief and Recovery Fund-designated monies.43 The report accompanying the House version of the bill (H.Rept. 115-829, H.R. 6385) would direct $50 million in FY2019 funds available for stabilization programs "for assistance to support the safe return of displaced religious and ethnic minorities to their communities in Iraq." Table 4. U.S. Assistance to Iraq: Select Obligations, Allocations, and Requestsin millions of dollars

Account

FY2012 Obligated

FY2013 Obligated

FY2014 Obligated

FY2015 Obligated

FY2016 Obligated

FY2017 Actual

FY2018 Req.

FY2019 Req.

FMF

79.555

37.290

300.000

150.000

250.000

250.00

-

-

ESF/ ESDF

275.903

128.041

61.238

50.282

116.452

553.50

300.000

150.000

INCLE

309.353

-

11.199

3.529

-

0.20

-

2.000

NADR

16.547

9.460

18.318

4.039

38.308

56.92

46.860

46.860

DF

0.540

26.359

18.107

-

.028

-

-

IMET

1.997

1.115

1.471

0.902

0.993

0.70

1.000

1.000

Total

683.895

202.265

410.333

208.752

405.781

1061.12

347.860

199.860

Sources: Obligations data derived from U.S. Overseas Loans and Grants (Greenbook), January 2017. FY2016-FY2019 data from State Department Congressional Budget Justification and other executive branch documents.

Notes: FMF = Foreign Military Financing; ESF/ESDF = Economic Support Fund/Economic Support and Development Fund; INCLE = International Narcotics Control and Law Enforcement; NADR = Nonproliferation, Antiterrorism, Demining, and Related Programs; DF = Democracy Fund; IMET = International Military Education and Training. The FY2018 foreign operations appropriations act (Division K, P.L. 115-141) stated that funds shall be available for stabilization in Iraq, and U.S. support to stabilization programs is ongoing using funds appropriated in FY2017. Since mid-2016, the executive branch has notified Congress of its intent to obligate $265.3 million in assistance funding to support UNDP FFS programs, including post-IS stabilization funding made available in the December 2016 continuing resolution (Division B of P.L. 114-254, see textbox below).44 Trump Administration requests for FY2018 and FY2019 monies for Iraq programs included requests to fund continued U.S. contributions to post-IS stabilization programs. No new contributions to U.N.-managed stabilization programs have been announced in 2018.The United States also contributes to Iraqi programs to stabilize the Mosul Dam on the Tigris River, which remains at risk of collapse due to structural flaws, overlooked maintenance, and its compromised location. The State Department notes that Iraq is working to stabilize the dam, but "it is impossible to accurately predict the likelihood of the dam's failing…."45

|